Team:Carnegie Mellon/KillerRed

From 2013.igem.org

Enpederson (Talk | contribs) |

Enpederson (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:Team:Carnegie_Mellon/Templates/header}} | {{:Team:Carnegie_Mellon/Templates/header}} | ||

| - | <html><h2>KillerRed's structure, chemistry and biophysical properties</h2></html> | + | <html><br><br> |

| + | <h2>KillerRed's structure, chemistry and biophysical properties</h2></html> | ||

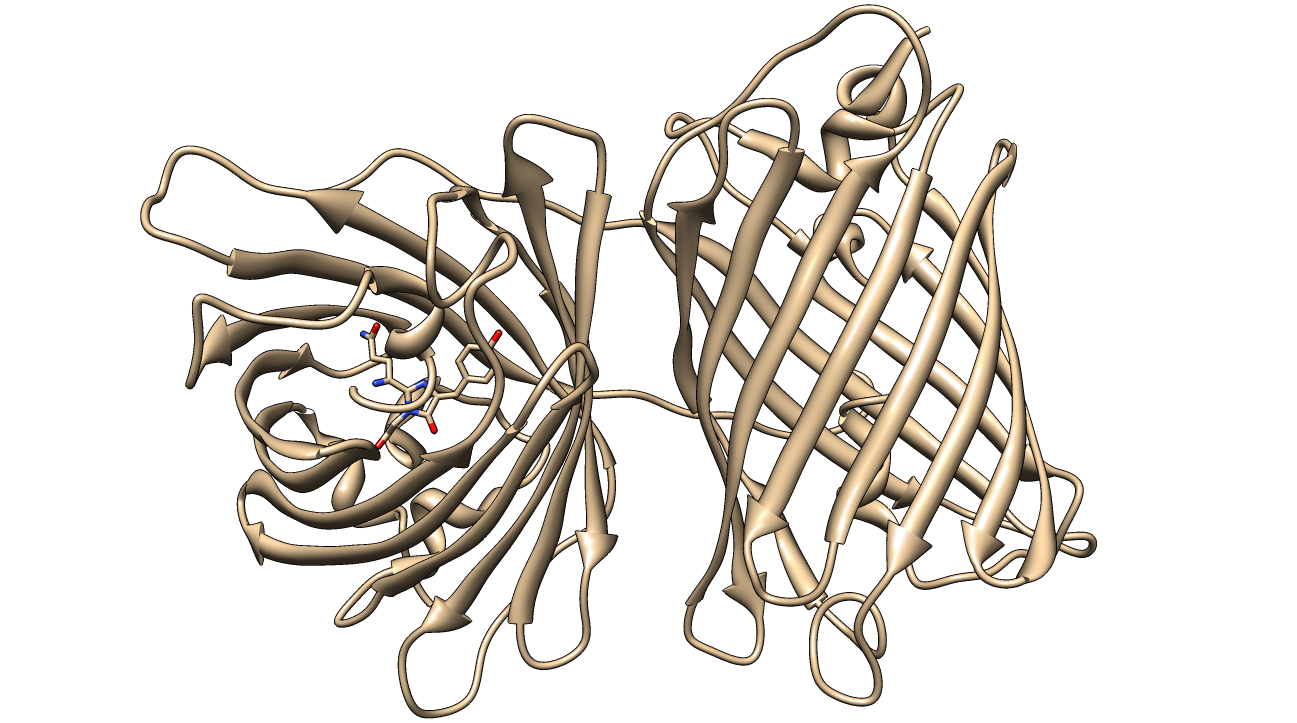

[[image:KillerRed.png|600px|thumb|center|<b>Figure 1: </b>Crystal Structure of KillerRed (PDB ID: 3GB3) with the QYG chromophore shown<sup>2,3,4</sup>]] | [[image:KillerRed.png|600px|thumb|center|<b>Figure 1: </b>Crystal Structure of KillerRed (PDB ID: 3GB3) with the QYG chromophore shown<sup>2,3,4</sup>]] | ||

Revision as of 03:32, 25 September 2013

KillerRed's structure, chemistry and biophysical properties

KillerRed is a red fluorescent protein that produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the presence of yellow-orange light (540-585 nm). KillerRed is engineered from anm2CP to be phototoxic. It has been shown that KillerRed produces superoxide radical anions by reacting with water. Superoxide reacts with the chromophore of KillerRed, causing it to become dark, which ultimately gives rise to a bleaching effect. KillerRed is spectrally similar to mRFP1 with a similar brightness. KillerRed is oligomeric and may form large aggregates in cells. Expression of KillerRed and irradiation with light may act a kill-switch for biosafety applications.

The structure of KillerRed has been analyzed and the structural basis for its toxicity has been explored. The relevant PDB IDs are 2WIQ and 2WIS for the fluorescent and dark states, respectively.

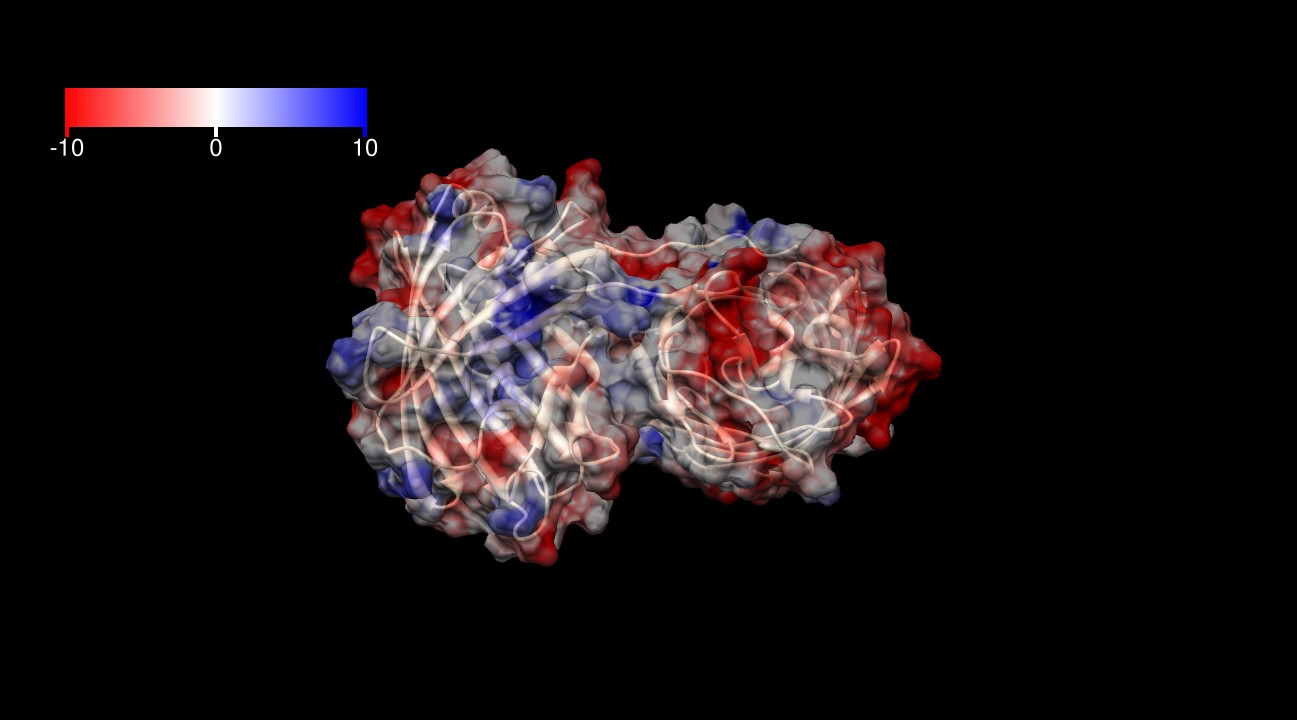

The surface of KillerRed is predominantly negatively charged as shown in Figures 3-6. The theoretical charge at pH 7.4 is approximately -13 (pI=5.1), which may play a role in its toxicity by interacting more closely with positively charged proteins and positively charged regions of proteins.

The interface between the homodimer includes a large network of hydrophobic interactions. This is a phenylalanine- and leucine-rich interface. The H148 residue forms two hydrogen bonds that "connect" the two backbones of the ß-barrels. The histidines and their hydrogen bonds are depicted in Figure 7.

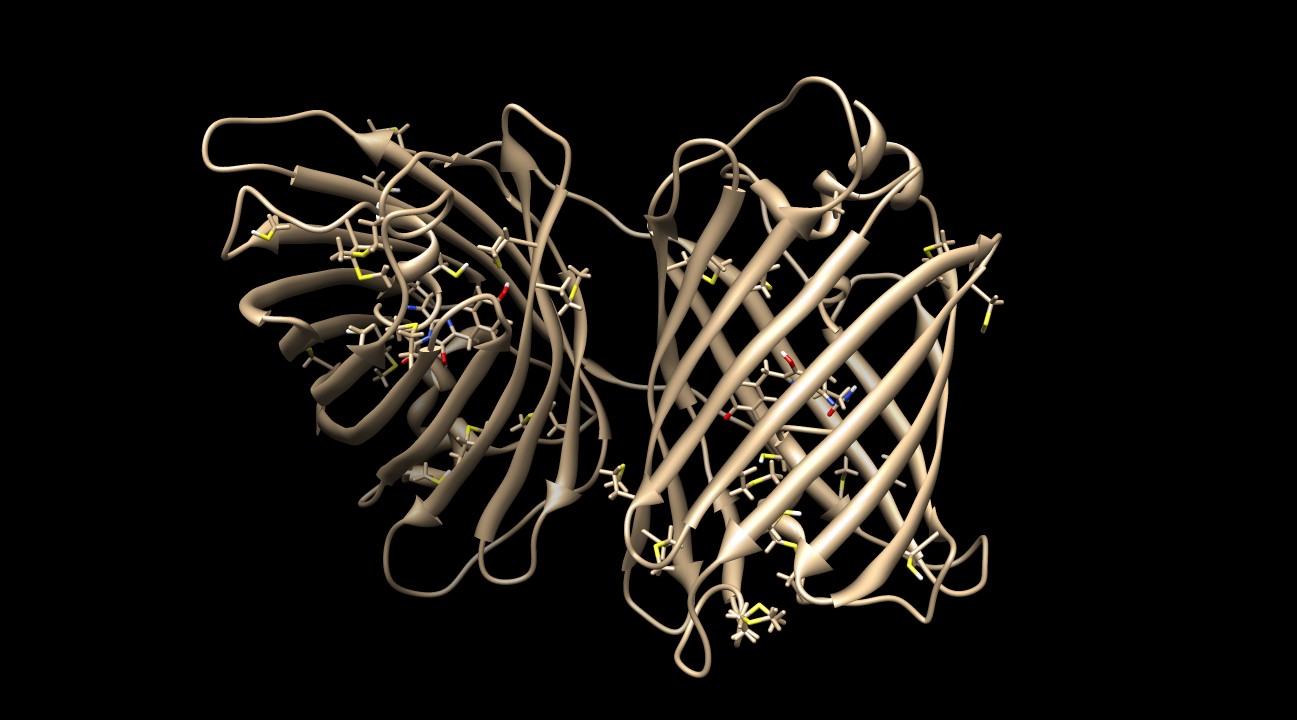

KillerRed contains many sulfurous residues (10 methionines and 6 cysteines) to protect the protein against ROS damage2. Figure 8 depicts the homodimer with these residues visible.

The superoxide anion radical is likely formed in this 8-membered water channel depicted in Figures 10 and 112. The carbonyl on the imidazole ring (Figure 9) hydrogen bonds with the water molecules and reacts with them when the π-electrons in the chromophore are excited. The lifetime of the fluorescence allows enough time for the reaction to occur and the superoxide to be produced2. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that fluorescent proteins are light-induced electron donors6, which would allow for the electron transfer to the water molecules, causing the superoxide to form.

References

1 Bulina, Maria E, Chudakov, Dmitriy M, Britanova, Olga V, Yanushevich, Yurii G, Staroverov, Dmitry B, Chepurnykh, Tatyana V, Merzlyak, Ekaterina M, Shkrob, Maria A, Lukyanov, Sergey, Lukyanov and Konstantin A.

A Genetically Encoded Photosensitizer

Nature Biotechnology 2006 24: 95-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt1175

2 Sergei Pletnev, Nadya G. Gurskaya, Nadya V. Pletneva, Konstantin A. Lukyanov, Dmitri M. Chudakov, Vladimir I. Martynov, Vladimir O. Popov, Mikhail V. Kovalchuk, Alexander Wlodawer, Zbigniew Dauter, and Vladimir Pletnev.

Structural Basis for Phototoxicity of the Genetically Encoded Photosensitizer KillerRed

Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009 284: 32028-32039. First Published on September 8, 2009, doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.054973

3Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package. Chimera is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources (2P41RR001081) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (9P41GM103311).

4Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE.

UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis.

Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004 Oct;25(13):1605-12.

5Takemoto K, Matsuda T, Sakai N, Fu D, Noda M, Uchiyama S, Kotera I, Yoshiyuki A, Horiuchi M, Fukui K, Ayabe T, Inagaki F, Suzuki H, Nagai T. SuperNova, a monomeric photosensitizing fluorescent protein for chromophore-assisted light inactivation. Sci. Rep. 2013/09/17/online. 3. Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep02629

6Bogdanov, Alexey M, Mishin, Alexander S, Yampolsky, Ilia V, Belousov, Vsevolod V, Chudakov, Dmitriy M, Subach, Fedor V, Verkhusha, Vladislav V, Lukyanov, Sergey, Lukyanov, Konstantin A. Green fluorescent proteins are light-induced electron donors. Nat Chem Biol. 2009/07//print. 5(7): 459-461. Nature Publishing Group http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.174

"

"