Team:Washington/LightSensing

From 2013.igem.org

(→Results) |

|||

| (118 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

=='''Background'''== | =='''Background'''== | ||

| + | |||

<html> | <html> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Recently, techniques have been developed that afford researchers the ability to control gene expression with light. To date, sensors that respond to red, green, and blue wavelengths of light have been reported. Light induced expression of genes has a number of advantages over chemical induction methods. For example, light induced expression is cheaper than chemical methods, can be used to finely tune expression levels through modulations of intensity, and can be rapidly removed -- a feature lacking in chemical induction systems. Furthermore, many light expression systems are reversible, depending on the wavelength of light used. Finally, the ability to control the expression levels of multiple genes of interest simultaneously could have far reaching implications for tuning biosynthetic pathways. The use of chemical inducers for this application would likely prove to be difficult and cost prohibitive, but multichromatic gene induction represents a potential solution to this problem. To this end, the 2013 University of Washington iGEM team chose to continue a project we began in 2012 that is aimed at the development and characterization of a set of tools that bring multichromatic gene expression into the realm of possibility for synthetic biologists. </p> | Recently, techniques have been developed that afford researchers the ability to control gene expression with light. To date, sensors that respond to red, green, and blue wavelengths of light have been reported. Light induced expression of genes has a number of advantages over chemical induction methods. For example, light induced expression is cheaper than chemical methods, can be used to finely tune expression levels through modulations of intensity, and can be rapidly removed -- a feature lacking in chemical induction systems. Furthermore, many light expression systems are reversible, depending on the wavelength of light used. Finally, the ability to control the expression levels of multiple genes of interest simultaneously could have far reaching implications for tuning biosynthetic pathways. The use of chemical inducers for this application would likely prove to be difficult and cost prohibitive, but multichromatic gene induction represents a potential solution to this problem. To this end, the 2013 University of Washington iGEM team chose to continue a project we began in 2012 that is aimed at the development and characterization of a set of tools that bring multichromatic gene expression into the realm of possibility for synthetic biologists. </p> | ||

| + | |||

In 2012, the University of Washington iGEM Team developed a freely available app for the Android operating system that affords spatiotemporal control over light wavelengths and intensities. When installed on an appropriate tablet (see <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Washington/ECOLIGHTTUNE">E.Colight</a>) the app could be useful for carrying out complex light induced expressions. In 2012, we were unable to fully characterize the app’s ability to control expression of light inducible genes. Thus, the 2013 iGEM Team’s goals include fully characterizing the app’s ability to control gene expression with light, and the development of a toolkit of light induced expression biobricks that are confirmed to work with the tablet app.</p> | In 2012, the University of Washington iGEM Team developed a freely available app for the Android operating system that affords spatiotemporal control over light wavelengths and intensities. When installed on an appropriate tablet (see <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Washington/ECOLIGHTTUNE">E.Colight</a>) the app could be useful for carrying out complex light induced expressions. In 2012, we were unable to fully characterize the app’s ability to control expression of light inducible genes. Thus, the 2013 iGEM Team’s goals include fully characterizing the app’s ability to control gene expression with light, and the development of a toolkit of light induced expression biobricks that are confirmed to work with the tablet app.</p> | ||

| Line 20: | Line 22: | ||

=='''Our System'''== | =='''Our System'''== | ||

| - | < | + | <blockquote> |

| - | + | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

| - | |||

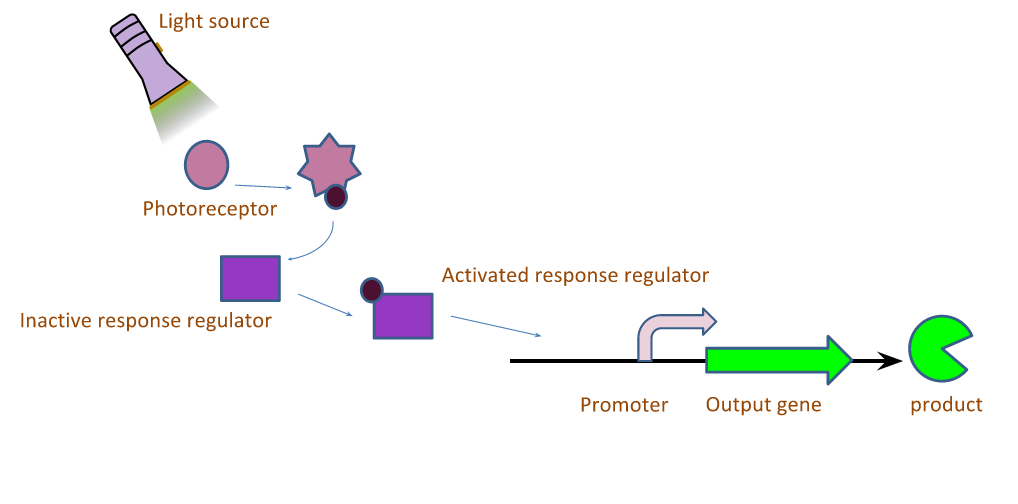

The light induced expression systems we used both require multiple protein components. In general, a small molecule chromophore is synthesized in the cell, and acts as a substrate for a transmembrane light sensing protein. When the protein sensor bound-chromophore-bound is exposed to light of the correct wavelength, a conformational change is induced in the sensor protein which in turn causes the phosphorylation of a transcription factor. The active form of the transcription factor then modulates the expression of any gene downstream of its cognate promoter. We worked with a red and green light inducible gene expression system this year. Both systems utilize the same chromophore, phycocyanobilin, but differ in the transmembrane light sensing proteins that bind the chromophore, and the downstream regulator proteins. The systems are described graphically in Figure 1.</p></p> | The light induced expression systems we used both require multiple protein components. In general, a small molecule chromophore is synthesized in the cell, and acts as a substrate for a transmembrane light sensing protein. When the protein sensor bound-chromophore-bound is exposed to light of the correct wavelength, a conformational change is induced in the sensor protein which in turn causes the phosphorylation of a transcription factor. The active form of the transcription factor then modulates the expression of any gene downstream of its cognate promoter. We worked with a red and green light inducible gene expression system this year. Both systems utilize the same chromophore, phycocyanobilin, but differ in the transmembrane light sensing proteins that bind the chromophore, and the downstream regulator proteins. The systems are described graphically in Figure 1.</p></p> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| - | + | </html> | |

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | [[Image:W2013_PartsTable.jpg|border|450px|right|thumb|Table 1: Description of source plasmids and components.]] | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| - | <table align="right" border="1" style="font-size: | + | <!--table align="right" border="1" style="font-size:10px" cellpadding="0" style="height: 20px; margin=10em; line-height:0.1em; padding: 0px;" cellstyle="border:1px solid black;border-collapse:collapse;"> |

| + | |||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td colspan=3 align ="center" style="font-size:11px; height: 20px" height: 20px height="1">Table 1: Description of source plasmids and components</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| - | <th width="130">Source</p></th> | + | <th width="130" height="1">Source</p></th> |

<th width="200">Component</p></th> | <th width="200">Component</p></th> | ||

<th width="250">Function</p></th> | <th width="250">Function</p></th> | ||

| Line 46: | Line 53: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| - | <td>pPLPCB </p></td> | + | <td height="1">pPLPCB </p></td> |

| - | <td>Plac/ara </p></td> | + | <td height="1">Plac/ara </p></td> |

| - | <td>Hybrid lactose and arabinose promoter</p></td> | + | <td height="1">Hybrid lactose and arabinose promoter</p></td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 112: | Line 119: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

--> | --> | ||

| - | <tr> | + | <!--tr> |

<td>pEO100c </p></td> | <td>pEO100c </p></td> | ||

<td>POmpC-BBa_B0034-sfGFP </p></td> | <td>POmpC-BBa_B0034-sfGFP </p></td> | ||

| Line 142: | Line 149: | ||

<td>Output inverter</p></td> | <td>Output inverter</p></td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| - | </table> | + | </table--> |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<blockquote align="left"> <!--style="width:50em; margin-left:100px; margin: 1em auto"--> | <blockquote align="left"> <!--style="width:50em; margin-left:100px; margin: 1em auto"--> | ||

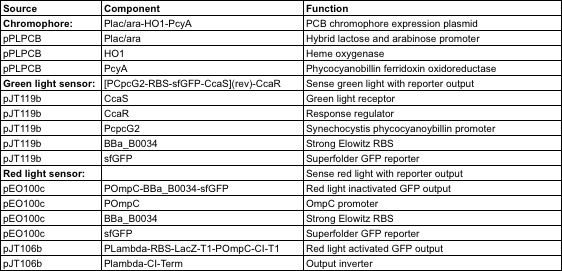

| - | The genes required to construct a functional light induced protein expression system were generously provided by Jeff Tabor at Rice University. Table 1.1 lists the genes required for each system and their respective functions. In order to construct a functional light responsive system, a multiple genes are transformed into E. coli. Regardless of the system in question, the minimal components required are: 1) genes utilized in the synthesis of the chromophore, 2) a transmembrane light sensing protein, and 3) response regulators which are activated by | + | The genes required to construct a functional light induced protein expression system were generously provided by Jeff Tabor at Rice University. Table 1.1 lists the genes required for each system and their respective functions. In order to construct a functional light responsive system, a multiple genes are transformed into E. coli. Regardless of the system in question, the minimal components required are: 1) genes utilized in the synthesis of the chromophore, 2) a transmembrane light sensing protein, and 3) response regulators which are activated by the light sensitive proteins, and ultimately function as transcription factors. |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| Line 155: | Line 162: | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | + | <!--html> | |

| - | <html> | + | |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

<p align="left">Table 1: Description of source plasmids and components </p> | <p align="left">Table 1: Description of source plasmids and components </p> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| - | </html> | + | </html--> |

| - | < | + | <html><h1 id='Methods'><p align=right><a href="#Methods"><font size="3">[Top]</font></p></a></h1></html> |

| - | + | ||

=='''Methods'''== | =='''Methods'''== | ||

| Line 168: | Line 173: | ||

'''Cloning''' | '''Cloning''' | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| - | + | Each light-responsive biosensor is composed of two or three plasmids, which requires three vectors with compatible origins of replication and orthogonal antibiotics. To subclone the light responsive operons into BioBricks, we selected equivalent copy number and antibiotic iGEM vectors. Because tetracycline is more common in iGEM vectors than spectinomycin, we cloned the chromophore operon into pSB3T5. | |

| - | Each light-responsive biosensor is composed of two or three plasmids, which requires three vectors with compatible origins of replication and orthogonal antibiotics. To subclone the light responsive operons into | + | |

| - | + | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<table> | <table> | ||

| - | <table border="1"> | + | <table border="1" style="font-size:11px" > |

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td colspan=7 align ="center" style="font-size:11px; height: 20px" height: 20px height="1">Table 2: iGEM Cloned Plasmids</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<th>Source Vector</th> | <th>Source Vector</th> | ||

| Line 180: | Line 186: | ||

<th>Copy Number</th> | <th>Copy Number</th> | ||

<th>Antibiotic</th> | <th>Antibiotic</th> | ||

| - | <th> | + | <th>BioBrick Equivalent</th> |

<th>Antibiotic</th> | <th>Antibiotic</th> | ||

| - | <th> | + | <th>BioBrick Name</th> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 223: | Line 229: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | Plasmids were transformed into either XL1-blue or DH5a cells and DNA was harvested after overnight growth using a miniprep kit from Qiagen. Genes of interest were amplified using | + | Plasmids were transformed into either XL1-blue or DH5a cells and DNA was harvested after overnight growth using a miniprep kit from Qiagen. Genes of interest were amplified using oligonucleotides with a BioBrick prefix and suffix added on to the ends, plus 3-6 extra basepairs recommended by NEB for efficient cutting. Operons from pPLPCB, pJT119b and pEO100c were amplified and made compatible with insertion into the pSB1C3 backbone between its prefix and suffix; pJT106b was also put into pSB4A5. |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| + | '''Light Experiments''' | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| - | This year our team | + | This year our team optimized a protocol our specific system. Overnight cultures were grown of E. coli containing plasmids with genes for all of the parts of the light system. The next morning, these cultures were used to inoculate either M9 media or M9 agar. The app was set up for the appropriate container and light conditions, and the “dark” plate was covered in aluminum foil. These plates were placed on the tablet and grown in a 37°C incubator. Cell density (absorbance) and GFP output (fluorescence) were then measured using a plate reader. We ran multiple experiments using this general protocol, including a timecourse, intensity test, blinking test, and plate image test. |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| + | <html><h1 id='Results'><p align=right><a href="#Results"><font size="3">[Top]</font></p></a></h1></html> | ||

=='''Results'''== | =='''Results'''== | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<html> | <html> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | [[Image:Washington_timecourse.png|border| | + | [[Image:Washington_timecourse.png|border|400px|right|thumb|Figure 2: GFP Output as a function of Green Light Induction Time.]] |

| - | + | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

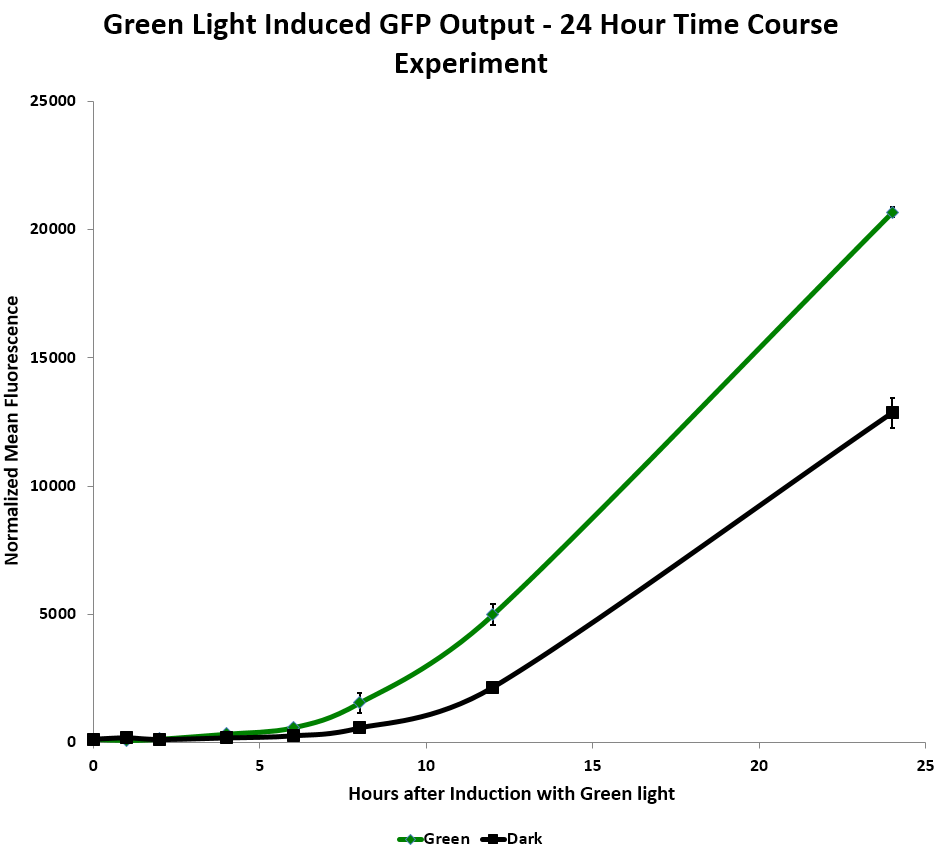

| - | We tested relative induction levels over time by measuring the change of fluorescence over multiple time periods. When exposed to green light continuously on a shaker in liquid culture over 24 hours, GFP levels in the system increased. | + | We tested relative induction levels over time by measuring the change of fluorescence over multiple time periods. When exposed to green light continuously on a shaker in liquid culture over 24 hours, GFP levels in the system increased. In the red light repressed GFP system, the red light repressed some GFP production after a few hours. However, the fluorescence increased dramatically in both dark and light systems after 12 hours, which implies that the red repressor may be leaky. |

| - | + | (Figure 2) | |

| - | + | <br><br><br> | |

| - | <br><br> | + | |

| - | + | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | [[Image:Washington_Light_Intensity_Data.png|border| | + | [[Image:Washington_Light_Intensity_Data.png|border|410px|left|thumb|Figure 3: Normalized Mean Fluorescence as a Function of Light Intensity.]] |

| + | <br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | [[Image:Washington_Blinking_Data.png|400px|right|thumb|Figure 4: Normalized Mean Fluorescence as a function of amount of green light per minute (ms).]] | ||

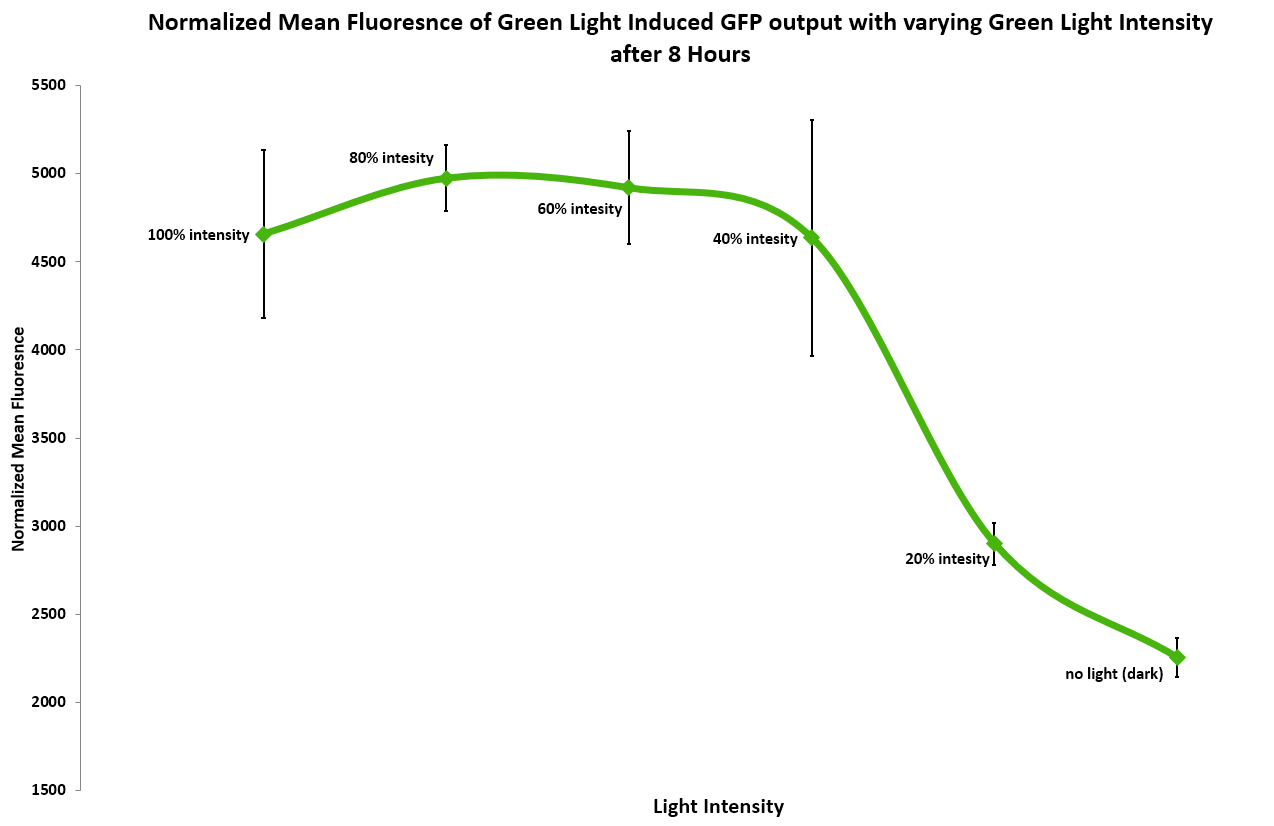

| + | (Figure 3) In addition, we measured the effect of light intensity on induction levels. Above 20% intensity the resulting GFP fluorescence was consistent, but it dropped at or below 20%. 40% and above gave the maximum level of induction. <br><br> | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | [[Image: | + | <br><br><br> |

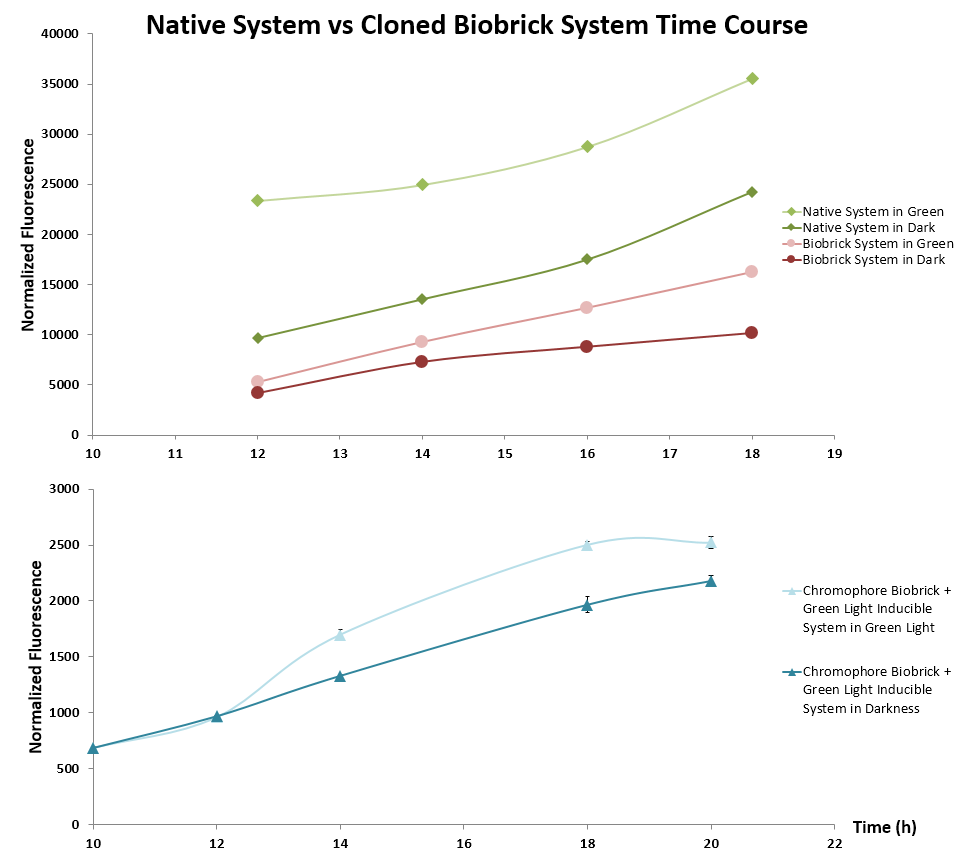

| + | [[Image:UW_Uwvtabor.png|410px|left|thumb|Figure 5: Native versus Biobrick systems over time.]] | ||

| + | <br><br><br> | ||

| + | <br><br><br> | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | We cloned CcaS, CcaR and sfGFP from pJT119b, and the chromophore producing genes | + | (Figure 4) We tested different lengths of stopping the light between longer periods of light, with up to a second in darkness. Most of our tests in flashing light seemed to be inconclusive. <br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> |

| + | (Figure 5) We cloned CcaS, CcaR and sfGFP from pJT119b, and pPLPCB which contains the chromophore producing genes ho1 and pycA. These parts were then tested using the standard GFP output protocol against the verified light system plasmids. Green light induced expression of GFP over the dark control, confirming the functionality of these BioBrick plasmids. However, the growth rate was relatively slower than that of the control plasmids. We hypothesize that this difference is due to the use of different antibiotic resistance genes between plasmids. <br><br> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | [ | + | <html><h1 id='Future'><p align=right><a href="#Future"><font size="3">[Top]</font></p></a></h1></html> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | < | + | |

=='''Future Plans'''== | =='''Future Plans'''== | ||

| + | |||

<html> | <html> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

The potential for the use of mobile devices to facilitate light-induced expression of proteins could have far reaching impacts for synthetic biologists, iGEM teams, for those hoping to conduct biological research with limited resources. Complex spatial patterning and even simple gradients of light intensity and color would likely be of great use to the synthetic biology community. Spatial control allows the induction of cellular patterns to simulate signalling gradients in tissue development and are useful in lithography and other pattern related technology.</p> | The potential for the use of mobile devices to facilitate light-induced expression of proteins could have far reaching impacts for synthetic biologists, iGEM teams, for those hoping to conduct biological research with limited resources. Complex spatial patterning and even simple gradients of light intensity and color would likely be of great use to the synthetic biology community. Spatial control allows the induction of cellular patterns to simulate signalling gradients in tissue development and are useful in lithography and other pattern related technology.</p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[Image:UW_EColight.jpg|150px|left|thumb|E.Colight: Google Play]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

Expanding the development of our light-inducing app will give iGEM researchers the ability to express gene products and initiate circuits simply with light in varying intensities for a range of expression levels. The 96-well format allows for the testing of many different constructs at the same time, greatly increasing the potential experimental throughput.</p> | Expanding the development of our light-inducing app will give iGEM researchers the ability to express gene products and initiate circuits simply with light in varying intensities for a range of expression levels. The 96-well format allows for the testing of many different constructs at the same time, greatly increasing the potential experimental throughput.</p> | ||

| - | + | Our proposal of a ‘hot-swappable’ designer Biobrick will allow researchers to exchange sfGFP with any custom output desired. For example, a LacZ reporter could be used with the to create conventional ‘Coliroid’ images. Additional fluorescent outputs such as RFP and CFP could be used to create separate and distinguishable signals. This will allow us to extend testing of red and green light sensors together on the same plate.</p> | |

| - | + | </html> | |

| - | Finally, we are testing the tablet for | + | <html> |

| - | + | Additionally, we would test the tablet app using a blue light inducible construct such as the LovTAP system presented in 2009 by EPF-Lausanne. Our app allows simultaneous expression on three separate chromatic channels that are compatible with blue light systems. Ultimately, these three signals could be used to create trichromatic output using RFP, GFP and CFP to recreate a full color image, from black and white Coliroid to vivid color bacterial photography.</p> | |

| - | + | ||

| + | Finally, we are testing the tablet for its capacity to be used as a portable incubator and expression system based on its heat output. Because of the high cost of purchasing a new incubator, we foresee this will be a boon to any iGEM team just starting out. It will allow more teams to enter the competition and make synthetic biology more accessible to high school programs. The tablet also reduces the space requirements to run both educational and high-throughput expression experiments, and could be utilized in resource-limited settings to induce and record data from biosensors in remote locations. The fact that many people already own a mobile tablet device allows them access to an inexpensive incubator by <a href = "https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.UWIgem.EColight&hl=en">downloading the app from Google Play.</a></p> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| - | |||

</html> | </html> | ||

| Line 277: | Line 289: | ||

=='''Parts Submitted'''== | =='''Parts Submitted'''== | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

This section serves as a quick lookup table for parts submitted for the 2013 Jamboree. | This section serves as a quick lookup table for parts submitted for the 2013 Jamboree. | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<groupparts>iGEM013 Washington</groupparts> | <groupparts>iGEM013 Washington</groupparts> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | < | + | <!--html> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

We also have an automatically generated <a href="http://partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2013&group=Washington">Team Parts</a> page.</html> | We also have an automatically generated <a href="http://partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2013&group=Washington">Team Parts</a> page.</html> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| - | <br /> | + | <br /--> |

| + | <html><h1 id='Sources'><p align=right><a href="#Sources"><font size="3">[Top]</font></p></a></h1></html> | ||

=='''Scientific Sources'''== | =='''Scientific Sources'''== | ||

| Line 295: | Line 304: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

J. J. Tabor, A. Levskaya, and C. A. Voigt, “Multichromatic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli,”<em> J. Mol. Biol</em>., vol. 405, no. 2, pp. 315–324, Jan. 2011.</p> | J. J. Tabor, A. Levskaya, and C. A. Voigt, “Multichromatic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli,”<em> J. Mol. Biol</em>., vol. 405, no. 2, pp. 315–324, Jan. 2011.</p> | ||

| - | C. Voigt, | + | C. Voigt, “Synthetic Biology, Part A: Methods for Part/Device Characterization and Chassis Engineering.”<em> Academic Press, 2011.</em></p> |

<p><br> | <p><br> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:01, 28 September 2013

Background

Recently, techniques have been developed that afford researchers the ability to control gene expression with light. To date, sensors that respond to red, green, and blue wavelengths of light have been reported. Light induced expression of genes has a number of advantages over chemical induction methods. For example, light induced expression is cheaper than chemical methods, can be used to finely tune expression levels through modulations of intensity, and can be rapidly removed -- a feature lacking in chemical induction systems. Furthermore, many light expression systems are reversible, depending on the wavelength of light used. Finally, the ability to control the expression levels of multiple genes of interest simultaneously could have far reaching implications for tuning biosynthetic pathways. The use of chemical inducers for this application would likely prove to be difficult and cost prohibitive, but multichromatic gene induction represents a potential solution to this problem. To this end, the 2013 University of Washington iGEM team chose to continue a project we began in 2012 that is aimed at the development and characterization of a set of tools that bring multichromatic gene expression into the realm of possibility for synthetic biologists. In 2012, the University of Washington iGEM Team developed a freely available app for the Android operating system that affords spatiotemporal control over light wavelengths and intensities. When installed on an appropriate tablet (see E.Colight) the app could be useful for carrying out complex light induced expressions. In 2012, we were unable to fully characterize the app’s ability to control expression of light inducible genes. Thus, the 2013 iGEM Team’s goals include fully characterizing the app’s ability to control gene expression with light, and the development of a toolkit of light induced expression biobricks that are confirmed to work with the tablet app.

Our System

The light induced expression systems we used both require multiple protein components. In general, a small molecule chromophore is synthesized in the cell, and acts as a substrate for a transmembrane light sensing protein. When the protein sensor bound-chromophore-bound is exposed to light of the correct wavelength, a conformational change is induced in the sensor protein which in turn causes the phosphorylation of a transcription factor. The active form of the transcription factor then modulates the expression of any gene downstream of its cognate promoter. We worked with a red and green light inducible gene expression system this year. Both systems utilize the same chromophore, phycocyanobilin, but differ in the transmembrane light sensing proteins that bind the chromophore, and the downstream regulator proteins. The systems are described graphically in Figure 1.

The genes required to construct a functional light induced protein expression system were generously provided by Jeff Tabor at Rice University. Table 1.1 lists the genes required for each system and their respective functions. In order to construct a functional light responsive system, a multiple genes are transformed into E. coli. Regardless of the system in question, the minimal components required are: 1) genes utilized in the synthesis of the chromophore, 2) a transmembrane light sensing protein, and 3) response regulators which are activated by the light sensitive proteins, and ultimately function as transcription factors.

Our red and green light sensitive systems were constructed through transformation of a subset of the plasmids listed in Table 1 into BL21 E. coli cells. Our green light responsive system was constructed by transforming pPLPCB and pJT119b simultaneously. A red light responsive system was created by transforming pPLPCB, pCPH8, and pEO100c into E.coli. GFP was used as the output of both systems.

Methods

Cloning

Each light-responsive biosensor is composed of two or three plasmids, which requires three vectors with compatible origins of replication and orthogonal antibiotics. To subclone the light responsive operons into BioBricks, we selected equivalent copy number and antibiotic iGEM vectors. Because tetracycline is more common in iGEM vectors than spectinomycin, we cloned the chromophore operon into pSB3T5.

Table 2: iGEM Cloned Plasmids Source Vector Origin Copy Number Antibiotic BioBrick Equivalent Antibiotic BioBrick Name pJT119b ColE1,pMB1 100-300 Chloramphenicol pSB1C3 Chloramphenicol pBB_GonG pPLPCB p15A 20-30 Spectinomycin pSB3T5 Tetracycline pBB_PCB pEO100c pSC101 ~5 Ampicillin pSB4A5 Ampicillin pBB_RoffG pJT106b pSC101 ~5 Ampicillin pSB4A5 Ampicillin pBB_RonL

Plasmids were transformed into either XL1-blue or DH5a cells and DNA was harvested after overnight growth using a miniprep kit from Qiagen. Genes of interest were amplified using oligonucleotides with a BioBrick prefix and suffix added on to the ends, plus 3-6 extra basepairs recommended by NEB for efficient cutting. Operons from pPLPCB, pJT119b and pEO100c were amplified and made compatible with insertion into the pSB1C3 backbone between its prefix and suffix; pJT106b was also put into pSB4A5. Light ExperimentsThis year our team optimized a protocol our specific system. Overnight cultures were grown of E. coli containing plasmids with genes for all of the parts of the light system. The next morning, these cultures were used to inoculate either M9 media or M9 agar. The app was set up for the appropriate container and light conditions, and the “dark” plate was covered in aluminum foil. These plates were placed on the tablet and grown in a 37°C incubator. Cell density (absorbance) and GFP output (fluorescence) were then measured using a plate reader. We ran multiple experiments using this general protocol, including a timecourse, intensity test, blinking test, and plate image test.Results

We tested relative induction levels over time by measuring the change of fluorescence over multiple time periods. When exposed to green light continuously on a shaker in liquid culture over 24 hours, GFP levels in the system increased. In the red light repressed GFP system, the red light repressed some GFP production after a few hours. However, the fluorescence increased dramatically in both dark and light systems after 12 hours, which implies that the red repressor may be leaky. (Figure 2)

(Figure 3) In addition, we measured the effect of light intensity on induction levels. Above 20% intensity the resulting GFP fluorescence was consistent, but it dropped at or below 20%. 40% and above gave the maximum level of induction.

(Figure 4) We tested different lengths of stopping the light between longer periods of light, with up to a second in darkness. Most of our tests in flashing light seemed to be inconclusive.

(Figure 5) We cloned CcaS, CcaR and sfGFP from pJT119b, and pPLPCB which contains the chromophore producing genes ho1 and pycA. These parts were then tested using the standard GFP output protocol against the verified light system plasmids. Green light induced expression of GFP over the dark control, confirming the functionality of these BioBrick plasmids. However, the growth rate was relatively slower than that of the control plasmids. We hypothesize that this difference is due to the use of different antibiotic resistance genes between plasmids.

Future Plans

The potential for the use of mobile devices to facilitate light-induced expression of proteins could have far reaching impacts for synthetic biologists, iGEM teams, for those hoping to conduct biological research with limited resources. Complex spatial patterning and even simple gradients of light intensity and color would likely be of great use to the synthetic biology community. Spatial control allows the induction of cellular patterns to simulate signalling gradients in tissue development and are useful in lithography and other pattern related technology.Expanding the development of our light-inducing app will give iGEM researchers the ability to express gene products and initiate circuits simply with light in varying intensities for a range of expression levels. The 96-well format allows for the testing of many different constructs at the same time, greatly increasing the potential experimental throughput.

Our proposal of a ‘hot-swappable’ designer Biobrick will allow researchers to exchange sfGFP with any custom output desired. For example, a LacZ reporter could be used with the to create conventional ‘Coliroid’ images. Additional fluorescent outputs such as RFP and CFP could be used to create separate and distinguishable signals. This will allow us to extend testing of red and green light sensors together on the same plate. Additionally, we would test the tablet app using a blue light inducible construct such as the LovTAP system presented in 2009 by EPF-Lausanne. Our app allows simultaneous expression on three separate chromatic channels that are compatible with blue light systems. Ultimately, these three signals could be used to create trichromatic output using RFP, GFP and CFP to recreate a full color image, from black and white Coliroid to vivid color bacterial photography. Finally, we are testing the tablet for its capacity to be used as a portable incubator and expression system based on its heat output. Because of the high cost of purchasing a new incubator, we foresee this will be a boon to any iGEM team just starting out. It will allow more teams to enter the competition and make synthetic biology more accessible to high school programs. The tablet also reduces the space requirements to run both educational and high-throughput expression experiments, and could be utilized in resource-limited settings to induce and record data from biosensors in remote locations. The fact that many people already own a mobile tablet device allows them access to an inexpensive incubator by downloading the app from Google Play.Parts Submitted

This section serves as a quick lookup table for parts submitted for the 2013 Jamboree.

<groupparts>iGEM013 Washington</groupparts>

Scientific Sources

J. J. Tabor, A. Levskaya, and C. A. Voigt, “Multichromatic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli,” J. Mol. Biol., vol. 405, no. 2, pp. 315–324, Jan. 2011. C. Voigt, “Synthetic Biology, Part A: Methods for Part/Device Characterization and Chassis Engineering.” Academic Press, 2011.

"

"