Team:Exeter/Results

From 2013.igem.org

Fentwistle (Talk | contribs) |

Fentwistle (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

=== "Fixing" our images using pouring plastics === | === "Fixing" our images using pouring plastics === | ||

| - | [[File:Pouring_plastic_1.jpg|right|| | + | [[File:Pouring_plastic_1.jpg|right||300px|]] |

When working with modified organisms such as our colourful <i>E. coli</i>, you must always take into account that their exposure to the environment must be minimised. Once our bacterial photographs have "developed", we want to be able to preserve the image but prevent release of the bacteria into the environment. Considering that, once the image had been made, we can't reverse the process or use the bacteria to generate another picture, we can utilise techniques to fix the image with no concerns about keeping the <i>E. coli</i> alive. | When working with modified organisms such as our colourful <i>E. coli</i>, you must always take into account that their exposure to the environment must be minimised. Once our bacterial photographs have "developed", we want to be able to preserve the image but prevent release of the bacteria into the environment. Considering that, once the image had been made, we can't reverse the process or use the bacteria to generate another picture, we can utilise techniques to fix the image with no concerns about keeping the <i>E. coli</i> alive. | ||

Our initial idea was to insert a "kill-switch" into the bacteria to switch of the image development at a chosen moment, then seal the plates they were grown on to prevent any unwanted release. However, this seemed overly complicated considering that all we needed to do was kill the bacteria then seal them into a contained environment. We looked instead at trapping the cultures between layers of plastic. | Our initial idea was to insert a "kill-switch" into the bacteria to switch of the image development at a chosen moment, then seal the plates they were grown on to prevent any unwanted release. However, this seemed overly complicated considering that all we needed to do was kill the bacteria then seal them into a contained environment. We looked instead at trapping the cultures between layers of plastic. | ||

| + | [[File:Pouring_plastics_2.jpg|right||300px|]] | ||

| + | Our first test were using cultures of RFP, which exhibits a rich pink colour when grown overnight on LB agar plates overnight. We looked at using a clear, water based varnish (which is usually used for preserving craft works) and a thick, viscous epoxy resin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The clear varnish was not particularly successful. It seems like the reasonably high water content of the agar plates prevented the varnish from setting, and instead of being clear, the varnish was cloudy and difficult to see through (see images). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The epoxy resin was initially far more successful. It formed a thick, clear protective layer over the cultures; when it was set, we were even able to peel the plastic off the plates. However, the resin appeared to react very aggressively with the bacteria. The colours leaked into the agar, and the colonies did not stay intact when we peeled off the plastic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, after we spoke to the members of the Exeter Camera Club (see our [https://2013.igem.org/Team:Exeter/Outreach Outreach] page) they offered some alternative techniques. We were recommended to try [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gum_arabic gum arabic], which is a natural gum derived from tree sap. It has been used extensively in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithography lithography], certain forms of historical [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gum_printing photography], watercolours and even the food industry. As it is a natural gum of polysaccharides and glycoproteins, it should react less aggressively than the epoxy resin but still form a protective layer. However, gum arabic is water-soluble, which may be an issue with the LB agar, which contains a high water percentage. Unfortunately, as we only spoke to the Camera Club the day before the Wiki-freeze, we will be unable to upload any results from experimenting with gum arabic to our site, but hopefully we will have some pictures to bring to Lyon. | ||

=== Planned "Post-Freeze" Work === | === Planned "Post-Freeze" Work === | ||

Revision as of 09:22, 4 October 2013

Green Light Module

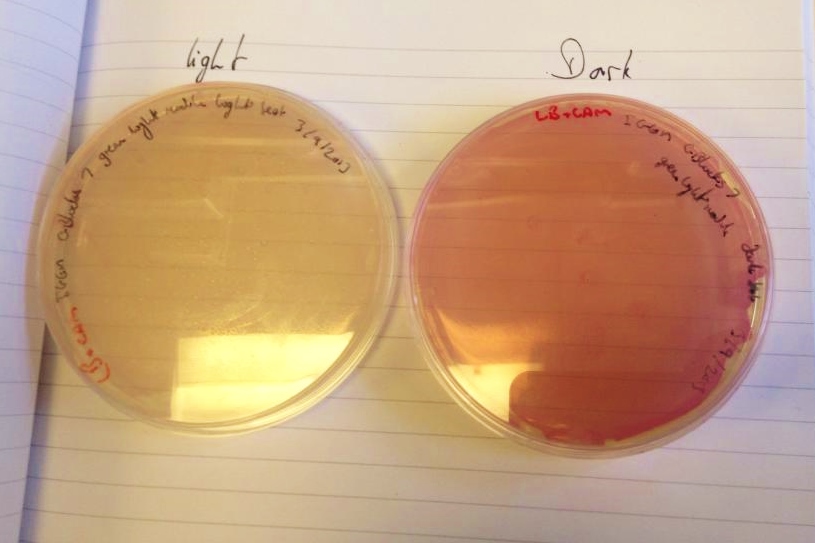

We have had marked success with our Green Light Module. Not only is the magenta pigment bright and evenly synthesised, but we have also managed to show magenta synthesis is inhibited by exposure to white light. We are currently working on showing that green light specifically switches off magenta production.

| our vibrant magenta pigment | clearly show magenta pigment | grown in dark vs. light |

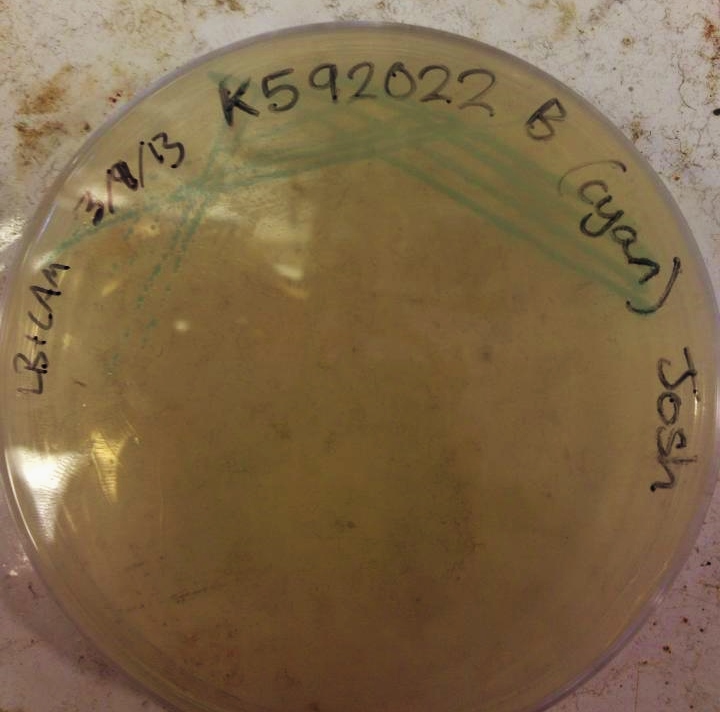

Cyan pigment

We managed to get our cyan pigment working in the labs after some difficulties with our digestions/ligations. The pigment takes a while to develop, over 24 hours compared to magenta's overnight development, but the colour is reasonably strong and is produced evenly by the cells. However, more time has been invested in the cyan pigment which is responsive to red light (see "Planned Post-Freeze Work").

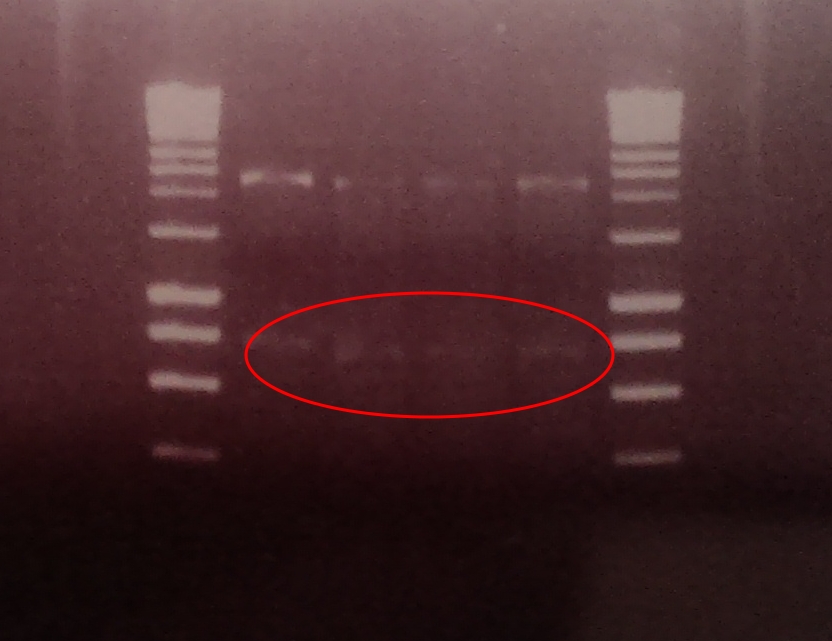

Red Light Module output Brick with BglII and BamHI restriction sites

| assembly parts showing superfolder GFP |

| output bricks showing band at around 950bp |

Our output brick for the Red Light Module includes the ompC promoter which is specific to the protein [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Porin_response:_osmoregulation_in_E.coli OmpR]. This is followed by an RBS and a restriction site for BglII and the coding region for a [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_E0040 GFP]. A second restriction site for BamHI follows, then a series of STOP codons to act as a terminator. The whole sequence is flanked by the iGEM prefix and suffix allowing the BioBrick to be used in 3A Assembly.

This BioBrick was built for us by IDT in their gBlock format. We designed the biobrick to contain a central GFP that is split between the two gBlocks, thus acting as a marker for a successful gibson assembly.

As the image shows, the two halves of GFP have been ligated together to form a complete, working protein in the successful Gibson assembly of our output bricks. GFP is constitutively expressed within DH5α cells as endogenous ENVZ phosporylates endogenous OmpR as a component of osmolarity sensing. Endogenous OmpR then binds to ompC. Thus our output brick is working as expected. In order to test whether the output brick can be implemented into the Red light pathway and ENVZ- strain should be used to avoid false positives.

A restriction digest was performed on 4 independent Gibson assembly products with BamHI and BglII to ascertain whether the restriction sites were implemented correctly into our brick. A gel electrophoresis of the digested parts showed two clear bands: plasmid DNA with ompC promoter and suffix at ~2300, and superfolder GFP coding sequence DNA at ~750. Both bands are in their expected position.

In order to insert a new part, we suggest following a standard primer based mutagenesis protocol to change the restriction sites to BamHI and BglII. Additionally when picking transformed colonies, screen for green fluorescence. These colonies' plasmids have ligated incorrectly. Colonies' plasmids that have no florescence should be miniprepped, digested and ran on a gel to check for the correct insert.

"Fixing" our images using pouring plastics

When working with modified organisms such as our colourful E. coli, you must always take into account that their exposure to the environment must be minimised. Once our bacterial photographs have "developed", we want to be able to preserve the image but prevent release of the bacteria into the environment. Considering that, once the image had been made, we can't reverse the process or use the bacteria to generate another picture, we can utilise techniques to fix the image with no concerns about keeping the E. coli alive.

Our initial idea was to insert a "kill-switch" into the bacteria to switch of the image development at a chosen moment, then seal the plates they were grown on to prevent any unwanted release. However, this seemed overly complicated considering that all we needed to do was kill the bacteria then seal them into a contained environment. We looked instead at trapping the cultures between layers of plastic.

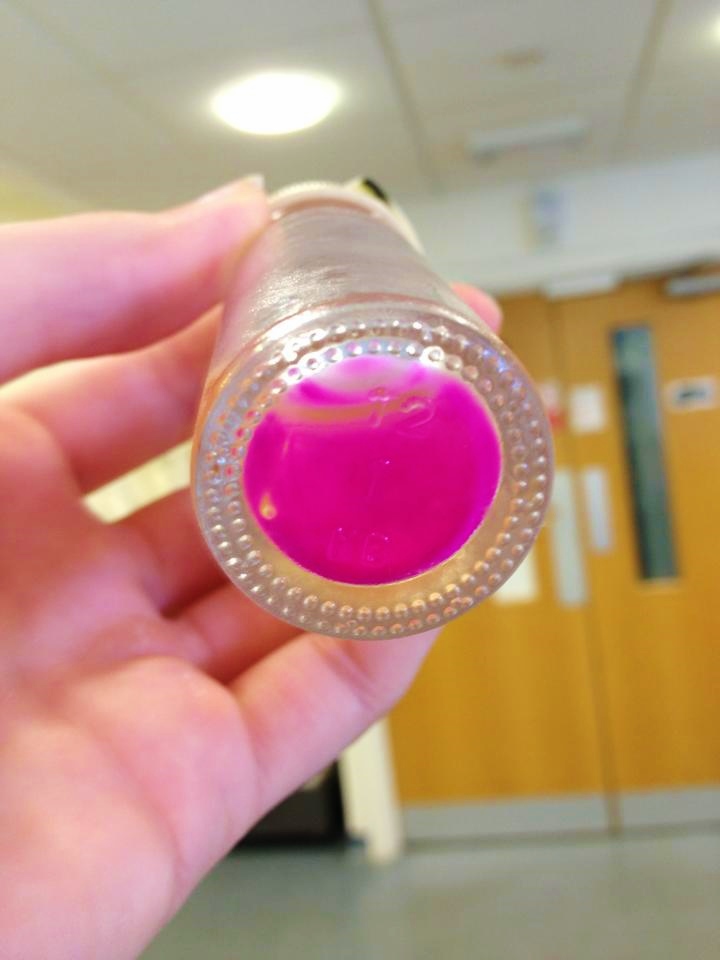

Our first test were using cultures of RFP, which exhibits a rich pink colour when grown overnight on LB agar plates overnight. We looked at using a clear, water based varnish (which is usually used for preserving craft works) and a thick, viscous epoxy resin.

The clear varnish was not particularly successful. It seems like the reasonably high water content of the agar plates prevented the varnish from setting, and instead of being clear, the varnish was cloudy and difficult to see through (see images).

The epoxy resin was initially far more successful. It formed a thick, clear protective layer over the cultures; when it was set, we were even able to peel the plastic off the plates. However, the resin appeared to react very aggressively with the bacteria. The colours leaked into the agar, and the colonies did not stay intact when we peeled off the plastic.

However, after we spoke to the members of the Exeter Camera Club (see our Outreach page) they offered some alternative techniques. We were recommended to try [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gum_arabic gum arabic], which is a natural gum derived from tree sap. It has been used extensively in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithography lithography], certain forms of historical [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gum_printing photography], watercolours and even the food industry. As it is a natural gum of polysaccharides and glycoproteins, it should react less aggressively than the epoxy resin but still form a protective layer. However, gum arabic is water-soluble, which may be an issue with the LB agar, which contains a high water percentage. Unfortunately, as we only spoke to the Camera Club the day before the Wiki-freeze, we will be unable to upload any results from experimenting with gum arabic to our site, but hopefully we will have some pictures to bring to Lyon.

Planned "Post-Freeze" Work

Blue Light Module

Our Blue Light Module, which is being built by DNA2.0, will unfortunately not arrive in the labs until after the Wiki-freeze. However, we will be bringing plenty of pictures of it working (hopefully!) to the Jamboree. Considering it has been constructed in a very similar manner to the Green Light Module, which is functioning in the lab, we are reasonably hopefully that we can have the Blue Light Module functioning in the lab soon after its arrival.

Red Light Module

We have successfully attached the OmpR specific promoter ompC to the cyan pigment coding region, and are now working on transforming the plasmid into EnvZ deficient cells (kindly provided to us by the Dundee iGEM 2013 Team).

This is due to OmpR and ompC being naturally present in most E. coli competent cells as part of this osmoregulation. EnvZ is the transmembrane protein which phosphorylates OmpR (to become OmpR-P) when osmolarity in the cell changes; its phosphorylation triggers the production of outer membrane porins. In our project, we only want OmpR to be phosphorylated when the cells are exposed to green or blue light, and for phosphorylation to halt when exposed to red light. Obviously, if OmpR-P is being formed outside of these rules, we will be getting pigment production (or lack thereof) when we have not allowed it, which will ruin the images we are trying to develop. Hence, we will express the Red Light Module in EnvZ deficient cells. The plasmid for the Red Light Module contains coding for EnvZ, but also for the second half of the transmembrane protein which allows our system to be light responsive; Cph1. EnvZ and Cph1 work together to form Cph8.

We came across multiple issues with the assembly of this pathway. These include: misunderstanding a part description causing cells to output the wrong colour pigment, 2012 kit plate Cph8 not being Cph8, transformation issues with home made competent cells and ligation inefficiencies brought about by attempting to ligate very small parts like [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_B0034?title=Part:BBa_B0034 BBa_B0034] to longer sequences.

Our work on the red light pathway uncovered that the coding sequence for [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K322124 BBa_K322124] when taken from the 2012 kit plates is not as stated on the registry. This part should have been an RBS and the coding region for Cph8, however sequencing revealed that it is actually the coding sequence for a human oestrogen receptor.

"

"