Team:Heidelberg/Templates/Delftibactin Results

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

===Producing Delftibactin=== | ===Producing Delftibactin=== | ||

| Line 37: | Line 38: | ||

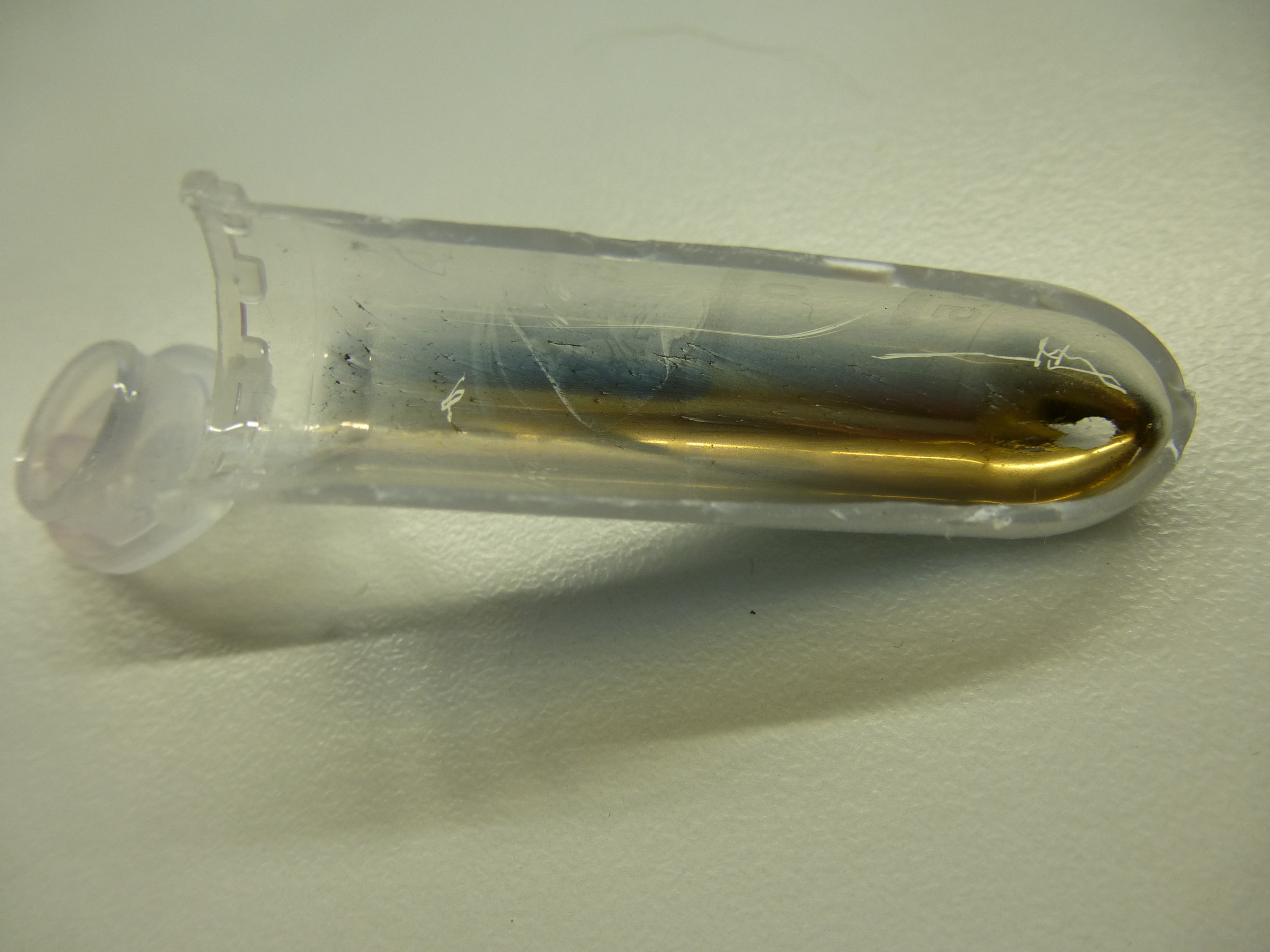

File:Heidelberg_IMG_4805.JPG| Figure 12: "Dissolved electronic waste" and ''D. acidovorans''. | File:Heidelberg_IMG_4805.JPG| Figure 12: "Dissolved electronic waste" and ''D. acidovorans''. | ||

File:Heidelberg_IMG_4818.JPG| Figure 13: "Dissolved electronic waste" on ''D. acidovorans'' | File:Heidelberg_IMG_4818.JPG| Figure 13: "Dissolved electronic waste" on ''D. acidovorans'' | ||

| - | File:Heidelberg_IMG | + | File:Heidelberg_IMG 4828.JPG| Figure 14: Precipitated "dissolved electronic waste" and ''D. acidovorans'' |

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Revision as of 19:22, 4 October 2013

Contents |

Producing Delftibactin

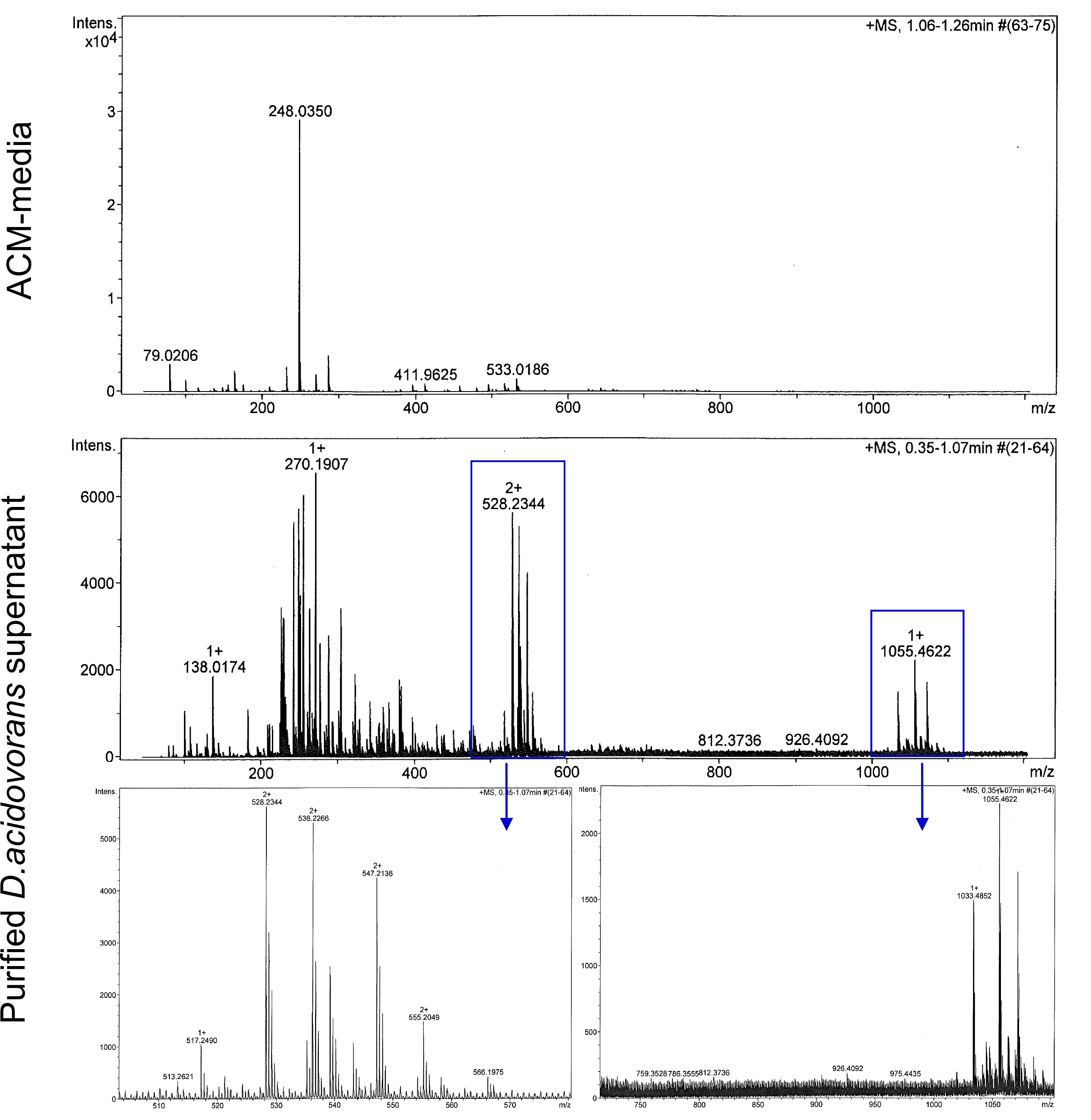

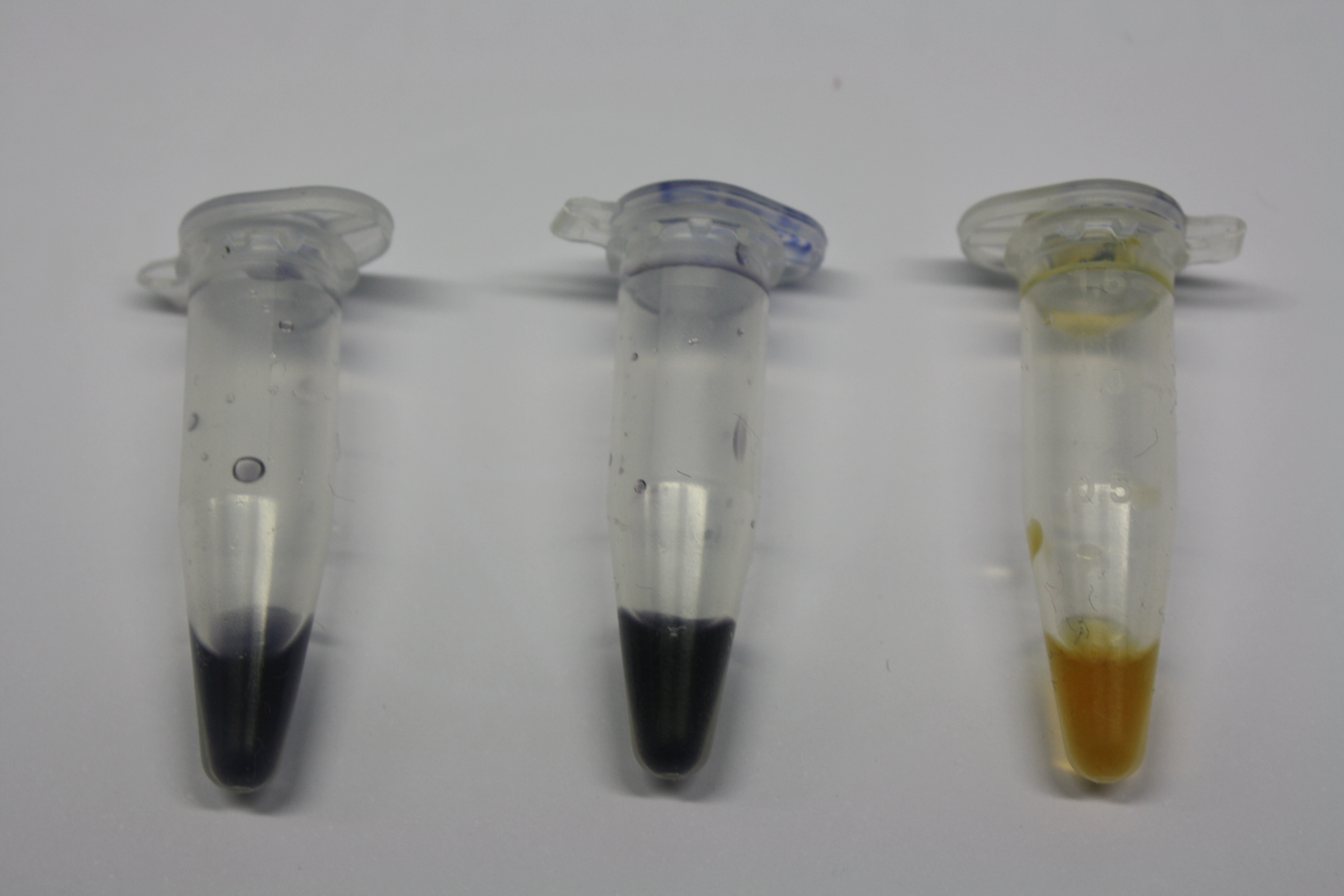

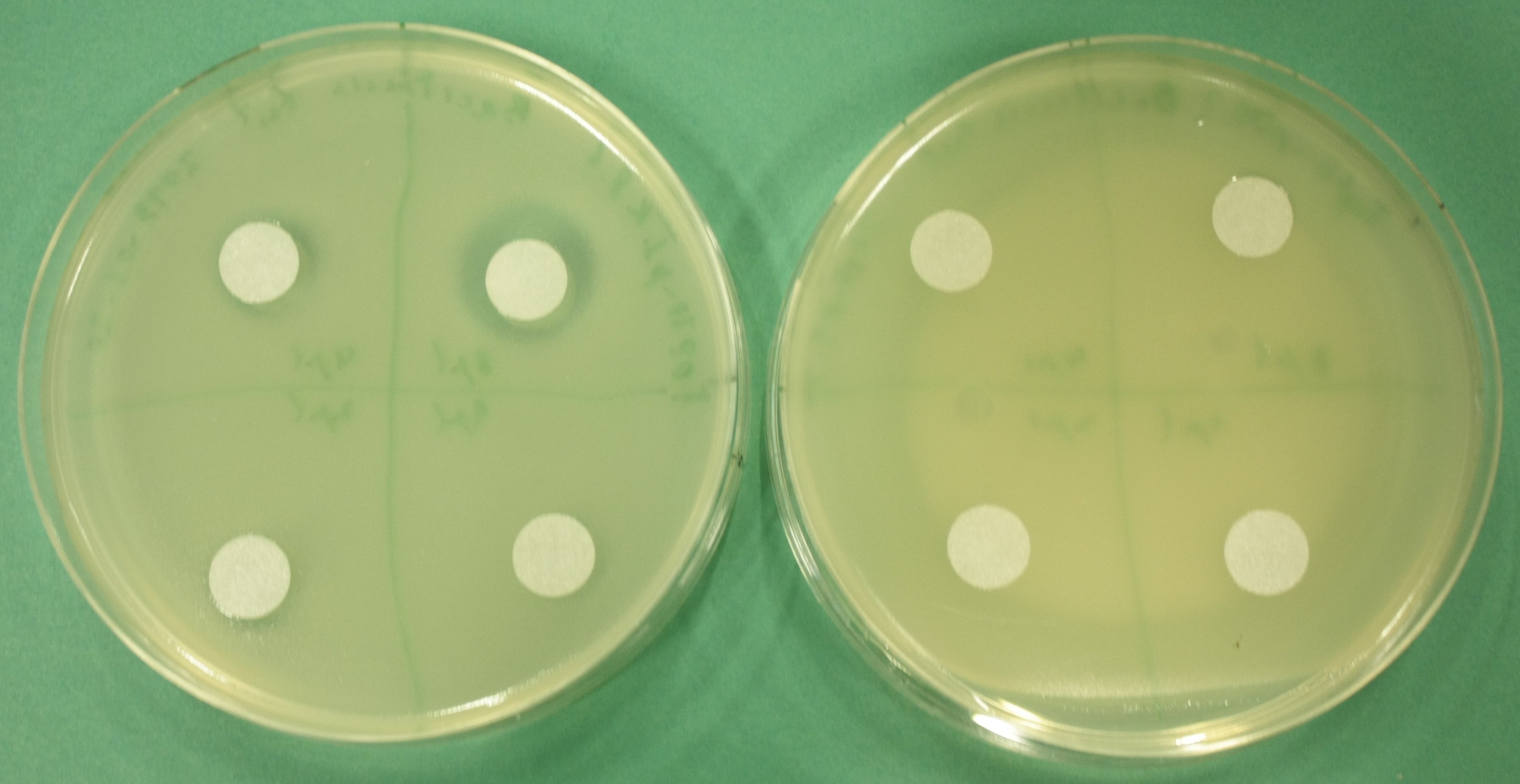

We obtained D. acidovorans DSM-39 from the ZSMZ and successfully reproduced the paper of Johnsson et al. (<bib id="pmid23377039"/>). In our experiments, precipitation on agar plates worked even better than described in the paper as shown in Figure 1. D. acidovorans is capable to precipitate solid gold from gold chloride solution as purple-black nanoparticles. Already at low concentrations of gold chloride, gold nonaparticles are precipitated increasing with concentration of gold chloride in solution (Fig. 2).

Using supernatants from the new Delftia acidovorans strain SPH-1, we showed precipitation of gold chloride solution to gold nanoparticles. Furthermore, we melted the purple-black nanoparticles to shiny solid gold as shown in figures 3 to 5.

We confirmed purification of Delftibactin using HP20 resin. Additionally, we proved precipitation of gold by the purified Delftibactin (figures 6 and 7) and detected it by Micro-TOF.

On the way to biological recycling by Delftibactin, we were able to dissolve gold-containing parts of an old CPU and established a protocol for recovery of gold as soluble gold salts from electronic waste (figures 9 to 11).

Moreover, we showed precipitation of dissolved gold recovered from electronic waste by D. acidovorans.

Adding this solution to D. acidovorans agar plates resulted in the formation of solid gold nanoparticles.

Taken together, we have successfully established a method enabling the recycling of pure gold from electronic waste using delftibactin produced by D. acidovorans.

Although the recycling was been working efficiently in our hands, the approach of using the natural D. acidovorans bacterial strain for delftibactin production on a larger scale has several disadvantages:

- a) D. acidovorans are relatively slow in growth (colony formation on plates occurs after 2-3 days)

- b) Efficient production of delftibactin requires the strain to be grown in ACM media, which is rather expensive compared to typical E. coli growth media, making the procedure less economic

Therefore, we wanted to engineer an E. coli strain producing delftibactin in high yields, thereby circumventing the abovementioned limitations. To this end, we first had to develop a thorough cloning strategy which would allow us to clone all necessary genes encoding the delftibactin-producing non-ribosomal peptide synthetases and polyketide synthetases from the del cluster (about 50 kb in total) and express them in E. coli alongside with the MethylMalonyl-CoA pathway providing one of the basic substrates in this pathway not naturally present in E. coli.

Amplification of the Del Cluster Genes

The first step towards introducing the Delftibactin pathway into E. coli was the amplification of the Del-cluster encoded on the genome of Delftia acidovorans. To this end, we designed Gibson primers and amplified the genes of the non-ribosomal peptide synthetase and the polyketide synthase (PKS) pathway as well as additional constitutive proteins, which were predicted to be necessary for the production of Delftibactin [1] . In the first weeks, PCRs were successfully established and optimized. At the same time, a separate plasmid was created encoding the PPTase from Bacillus subtilis and a permeability device [ BBa_I746200] [2] for the export of the synthesized NRP. Additionallly, plasmids from the partsregistry [3] were successfully transformed and amplified for the backbone generation.

Gibson Assembly & Transformation

As it is not trivial to assemble such a large number of long DNA fragments, we have used the Gibson Assembly method [4] implemented by Cambridge in iGEM 2010 instead of common cloning procedures such as restriction and ligation techniques. The assembled constructs of up to 32 kbp in size were transformed into E. coli via electroporation. Correct assembly of the fragments was tested by analytical restriction digest.

The exemplary restriction digest shown above (Fig. 15) confirms the correct assembly of the three desired constructs as it shows the expected band pattern expected from in silico digestion. Clones (6 and 9) contained the plasmid that encodes for the Methylmalonyl-CoA pathway (Fig. 15a). The obtained DNA sequences were sent in for sequencing over the gibson-assembled regions for confirmation. [5][6] The sequencing confirmed the accuracy of the sequence. The successful generation of DelRest plasmid was proven by different enzymatic restriction digests (Fig. 15b) and also attested by the sequencing. The sequence was compared with the available SPH1 sequence of the Del cluster of Delftia acidovorans in NEB-database [7] (For further information please visit our labjournal). This shows, that Gibson assembly is a suitable cloning approach for rapid assembly of large NRPS and PKS expression constructs.

Analytical restriction digest of DelH (Fig.15c) also gave rise to a number of positive clones. However, in contrary to the two successfully assembled and sequenced plasmids discussed above, the sequencing results derived from all DelH clones showed various mutations, which were mostly located within the region of the first DelH forward primer. Most of these mutations were deletions present at the very beginning of the DelH coding region. Interestingly, one specific deletion in the DNA sequence was found consistently in several independent clones. As we did not have any clone without mutations, we proceeded with the a DelH clone (termed C5), as this clone did not have any bp deletion but only harbored a minor base-pair substitution (leading to conversion of the DelH Alanine at position 10 to Threonine). Some exemplary sequences are listed below (Tab. 1) of Delftia acidovorans and two observed mutations in different DelH clones.

Tab.1 DelH 5’ sequence, in which most mutations were observed. The ATG start codon is depicted in bold. The table shows the sequence comparison between the DelH reference strand of D. acidovorans and two different exemplary E. coli clones transformed with the plasmid pHM04 (assembled DelH expression vector). The second line shows the accumulated deletion and the third line shows the clone containing 'only' single base pair substitution. Deletions appeared quite frequently while a substitution was only found in a single clone C5. The substitution changes the corresponding Alanine codon to Threonine.

| Organism | Plasmid containing | DNA -Sequence | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| D. acidovorans | none | ATG GACCGTGGC CGCCTGCGC CAAATCGC | correct |

| E. coli DH10ß | pHM04 | ATG GACCGTG-C CGCCTGCGC CAAATCGC | deletion |

| E. coli DH10ß C5 | pHM04 | ATG GACCGTGGC CGCCTGCGC CAAATCAC | substitution |

Due to the fact that E. coli seemed to somehow selected for mutated DelH clones, we hypothesize that expression of DelH in absence of the other proteins might be toxic for the cells. This would explain why E. coli selects for mutated, none functional, truncated DelH proteins. The same phenomenon of frequent mutations in presumably positive clones was also observed when we started cloning of the permeability device used in the pIK8 construct. The sequenced plasmids showed an unusually high accumulation of mutations compared to other constructs. In case of the methylmalonyl-CoA plasmid (pIK8), the problem was solved by the usage of a weak promoter and a weak ribosome binding site from the partsregistry for driving the expression of the permeability device. Based on this knowledge, DelH is currently being re-assembled into a new backbone (pSB6A1) [8] containing a weak promoter BBa_J23114 [9] and the ribosome binding site BBa_B0032[10]. While the new plasmid is constructed, the following experiments were performed with the C5 clone as we hypothesized, that pHM04 construct #C5 bearing the single nucleotide exchange at position 28 might still show expression of functional DelH when transformed into E. coli (the corresponding amino acid exchange is located at the N-terminus).

Therefore, we transformed all three plasmids, namely the pHM04 #C5 (encoding DelH), the DelRest plasmid (encoding all other del genes despite delH) and the pIK8 construct (bearing the MethylMalonyl-CoA pathway, the Sfp PPTase and the permeability device expression cassette) into E. coli DH10ß and E. coliBL21 DE3 in parallel. This should lead to E. coli cells producing delftibactin and secreting it into the media.

Expression of the Delftibactin NRPSs & Associated Genes

We carried out experiments to test whether our constructs enable expression of the delftibactin NRPS/PKS pathway in E. coli.

For expression of DelH and DelRest, we conducted SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie stainig. As negative controls we used untransformed cells and cells transformed only with the original plasmid backbones. The proteins DelE, DelG and DelH are significantly larger than any protein that is expressed by our host E. coli. Therefore, the expression of the introduced genes was clearly visible on the SDS-PAGE (Fig. 16). Even though the expression was weak, as we have expected for such a large proteins, clear distinct bands at the expected size of DelE and DelG were detected for the clone transformed with the DelRest plasmid and a band at the size of DelH for the clone transformed with the DelH plasmid. As the promoter in front of DelE and DelG controls the expression of DelA, DelB, DelC, DelD and DelF, too, one can assume simultaneous expression of these Del proteins.

For proving that E. coli also produces the permeability device, which is needed for export ofDelftibactin out of the cells, a Hemmhof agar diffusion test with bactracin was performed. Bacitracin is a very large antibiotic which is usually not able to diffuse across the cell membrane passively. Absent growth upon application of bacitracin of bacteria containing the plasmid while in the control cells without the device were not affected by the antibiotic (Fig. 17) confirms expression of the transporter.

In conclusion, we successfully expressed the recombinant Delftibactin NRPS/ PKS pathway as well as the required Methylmalonyl-CoA pathway, the PPTase and permeability device in E. coli.

We furthermore showed, that it is not only possible to assemble large plasmids (in sum these were about 64 kpb in total size in our case) and transform them into E. coli, but showed successful expression of large NRPS/PKS modules in our host strain.

"

"