Team:Valencia Biocampus/Modeling

From 2013.igem.org

Beta3designs (Talk | contribs) (→Group behavior) |

(→Chemotaxis of a single worm consuming attractant) |

||

| (49 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 164: | Line 164: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| - | ----<br/> | + | --------<br/> |

Bargmann CI (2006) <i>Chemosensation in </i>C. elegans. Wormbook <br/> | Bargmann CI (2006) <i>Chemosensation in </i>C. elegans. Wormbook <br/> | ||

Berg HC (1993) <i>Random walks in biology</i>. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.<br/> | Berg HC (1993) <i>Random walks in biology</i>. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.<br/> | ||

| Line 452: | Line 452: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| - | We also | + | We also carried out some simulations with different number of attractant sources. One can find simulations with $1$, $2$ and $3$ sources, and parameters $D\;=\;0.2$, $k\;=\;0.001$ (thus $D/k\;=\;200$) here:<br/> |

<html> | <html> | ||

<div class="accordion" id="Videos3-accordion"> | <div class="accordion" id="Videos3-accordion"> | ||

| Line 481: | Line 481: | ||

<div class="clearfix"></div><br/> | <div class="clearfix"></div><br/> | ||

| - | $$\ | + | Parameter identification in PDEs is a rather complex topic, we did some research concerning our Group Behavior Model which is a <html><a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fokker%E2%80%93Planck_equation"><i>Fokker-Planck Equation</i></a></html> with a somewhat complex drift term $\nu$, which depends on position in our model (it could also depend on more factors which would add even more complexity to the system and therefore we didn't study them). We weren't lucky enough to find anything related to the topic (at least with the time we had), so we thought about implementing our own algorithms, based on an <i>educated guess</i> (As usual all the code we wrote can be found under the <html><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Valencia_Biocampus/Devices#Software">Software section</a></html>). We wanted to study the <i>spatial time constant</i> of the system, that is, <b>how long does it take for the system to reach an stable spatial distribution?</b> We thought about a obtaining a variable <span style="font-size:14px;">$\mathcal{V}$</span> that would grow asimptotically after some time <span style="font-size:14px;">$\tau_{xy}$</span> (the spatial time constant). That is, our variable $\mathcal{V} \rightarrow C$ as $\tau_{xy} \rightarrow +\infty$. We then came up with the idea that local maxima would be a good way to define when the spatial distribution was stable, so we decided that the slower local maximum (that is the local maximum which is the slowest in stabilizing to its final position) would be a good approach to define the spatial time constant $\tau_{xy}$. |

| - | Where $D$ and $k$ are the mentioned parameters of the model and $log$ refers to the natural logarithm (base $e$). | + | <br/> |

| + | Therefore we needed an algorithm to calculate all the local maxima at a given instant and also to determine when they have "stopped" moving, so we programmed an approximate algorithm to find the local maxima in <i>SciLab</i> and used a more or less small band centered around the final value to determine $\tau_{xy}$. An example of the graphs we obtained through this process can be seen here: | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center; display: block;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d4/TauD1k001ident.png" rel="lightbox-group132" title="Identifying tau_xy"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d4/TauD1k001ident.png" class="thumbnail" width="300" height="226" style="float: none; display: inline" alt="tau_xy identification"/> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="clearfix"></div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | So we carried out several simulations with different values for our parameters $D$ and $k$, in order to obtain the forementioned relationship between $D$, $k$ and $\tau_{xy}$. | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | First of all, we managed to plot and obtain the function that relates $D$ with $\tau_{xy}$, for $k=0.00025,\;0.0003,\;0.000375,\;0.0005$ and $0.001$. And as one can observe, different values of $k$ just move the curves but the main shape of the functionals remains the same, that is, exponential (with rather great coefficients of determination). | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align: center; display: block;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/12/Tau_vs_D.png" rel="lightbox-groupb" title="tau_vs_D"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/12/Tau_vs_D.png" class="thumbnail" width="550" height="280" style="float: none; display: inline" alt="Solution"/> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | From the results we hypothesized that the general form of the functional (depending on $k$) was as follows: | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | $$D(\tau_{xy},k) = f(k)e^{\left(g(k)\tau_{xy}\right)}$$ | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

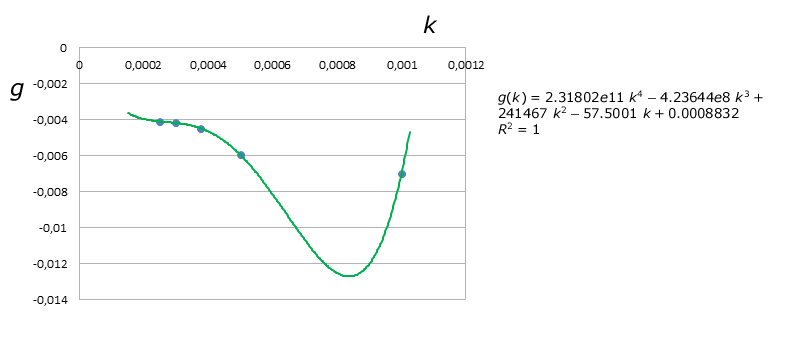

| + | We then plotted the coefficients $f(k)$ and $g(k)$ vs. $k$, as shown here: | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d9/F%28k%29.png" rel="lightbox-groupb" title="tau_vs_D"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d9/F%28k%29.png" class="thumbnail" width="550" height="280" style="float: none; display: inline" alt="Solution"/> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/ee/G%28k%29.png" rel="lightbox-groupb" title="tau_vs_D"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/ee/G%28k%29.png" class="thumbnail" width="550" height="280" style="float: none; display: inline" alt="Solution"/> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We first obtained a quadratic regression and the resulting equations for $f(k)$ and $g(k)$ were: | ||

| + | $$f(k) = 3e6\;k^2 - 4658.1\;k+1.9523$$ | ||

| + | $$g(k) = 6177.4\;k^2 - 11.907\;k-0.0013$$ | ||

| + | But $R^2$ was about $80.17\%$ for $f(k)$, way too low, so then we decided to obtain a better model by using Lagrange's Interpolating Polynomials, which are represented by the green curves on the graphs above. Thus we obtained the following final equation for $D$: | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <span style="font-size:11px;">$$D(\tau_{xy},k) = \left(-3.4061e13\;k^4+4.22776e10\;k^3+3.2955e6\;k^2-15277\;k+4.19004 \right)\;e^{\left(2.31802e11\;k^4-4.23644e8\;k^3+241467\;k^2-57.5001\;k+0.0008832 \right)\;\tau_{xy}}$$</span> | ||

| + | From this the equation for $\tau_{xy}$ can be obtained: | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <span style="font-size:11px;">$$\tau_{xy}(D,k) = \frac{1}{0.0008832 - 57.5001\; k + 241467\; k^2 - 4.23644e8\; k^3+2.31802e11\; k^4} log\left(\frac{D}{4.19004 - 15277\; k + 3.2955e6\; k^2 + 4.22776e10\; k^3 - 3.4061e13\; k^4}\right)$$</span> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | Where $D$ and $k$ are the mentioned parameters of the model and $\log$ refers to the natural logarithm (base $e$). | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | The average of the relative error is somewhat lower (at least in the studied region), about $8.00677\%$, compared to about $9.4\%$ for the first approximation. | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | From this equations we tried to obtain the parameters $D$ and $k$ for our model by stablishing a relationship that would not lead to dirac deltas in the final solution, which is what usually happened and is the theoretical solution provided the initial distribution of worms is also a dirac delta. Therefore we obtained the relationship $\frac{D}{k} = 502.2$ that would lead to a temporal stabilisation of the distribution, meaning no dirac deltas would arise. The intention was to provide our wetlab mates with theoretical data to improve their experiments and therefore creating a feedback loop in which they could provide data to us to improve our model even more and they would receive result back and so on. But, in fact, with the obtained relationship and our data we weren't able to find correct values for $D$ and $k$. We think this maybe due to the restricted region for $\tau_{xy}$, $D$ and $k$ that we studied. We also think that through the same process we would be able to achieve correct relationships for the variables in other regions of interests the problem is with increasingly small $D$ and $k$ parameters, come increasingly large times for the simulations to run and we weren't able to do so in our personal computers. This would therefore be a future task, to carry out more simulations maybe on a computer cluster with parallelization. We think that then the principles we followed would still hold. | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

----- | ----- | ||

Okopinska A. (2002) <i>Fokker-Planck equation for bistable potential in the optimized expansion</i>. Physical review E, Volume 65, 062101 <br/> | Okopinska A. (2002) <i>Fokker-Planck equation for bistable potential in the optimized expansion</i>. Physical review E, Volume 65, 062101 <br/> | ||

| Line 516: | Line 583: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<br/>As can be seen, a higher bacteria/concentration ratio is achieved in our system than the conventional one. Anyone can appreaciate that the ratio tends to one, being lower than the conventional case ratio, but in that region the substrate concentration is nearly zero. So it is not interesting to study. | <br/>As can be seen, a higher bacteria/concentration ratio is achieved in our system than the conventional one. Anyone can appreaciate that the ratio tends to one, being lower than the conventional case ratio, but in that region the substrate concentration is nearly zero. So it is not interesting to study. | ||

| - | <br/><br/>But one question arises: Is this significant? In fact, it is not. In both cases, the average ratio in the non-stirred case is the same as the stirred one. But it is not a drawback. It means that our system can perform the same as a conventional bioreactor but with the advantages of a higher concentration. Therefore, the production yield in higher. | + | <br/><br/>But one question arises: Is this significant? In fact, it is not. In both cases, the average ratio in the non-stirred case is the same as the stirred one. But it is not a drawback. <b>It means that our system can perform the same as a conventional bioreactor but with the advantages of a higher concentration. Therefore, the production yield in higher.</b> |

<br/><br/>In general, our system behaves as well as a conventional one for the stationary, linear, ideal case. Particular cases are not studied because they have to be analyzed independently. A complex model can be developed for each case to study its viability for its practical use, but it needs more time. Because of that, we made a cualitative study for the system. While time is a problem (stirring is faster than nematode crawling), higher yields and better suitability for several problems are important advantages of our system. Also, the combination of our model and the tracking device helps to determinate the final result. | <br/><br/>In general, our system behaves as well as a conventional one for the stationary, linear, ideal case. Particular cases are not studied because they have to be analyzed independently. A complex model can be developed for each case to study its viability for its practical use, but it needs more time. Because of that, we made a cualitative study for the system. While time is a problem (stirring is faster than nematode crawling), higher yields and better suitability for several problems are important advantages of our system. Also, the combination of our model and the tracking device helps to determinate the final result. | ||

Latest revision as of 08:49, 29 September 2014

Modeling

The main goal of our modeling project is to accurately predict the behavior of our system in several issues, from the mounting of bacteria on C. elegans to the performance of our worms reaching the place of interest. In order to do that, we use several modeling techniques.

The movement of C. elegans in the presence of a chemoattractant in order to carry our bacteria to that source is the main issue of our project, so we consider modeling this aspect and employing it as scaffold for the whole modeling project. Several layers show up that it must be modeled in different ways. In our approach, we mathematically describe each layer, from the simplest to the most complex, integrating each one.

The workflow in the C. elegans movement is the following:

| Single Worm Behavior | Single Worm Chemotaxis | Group Behavior | System performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Considerations | Chemoattractant | ||||

| Bacteria | |||||

| Modeling approach | Random Walk | Biased Random Walk | Partial Differential Equations | Ordinary Differential Equations | |

The model is improved adding the data obtained from the experiments in order to achieve a holistic model which can predict the distribution of our worms, the kinetics of the present bacteria and the concentration of the substrate in each moment.

Biobricks modeling

In this section, PHA production is modeled.

PHA production

By extracting data from fermentation assays we obtained a good simple linear regression by means of the least squares method between the dry weight of the microorganismos (Pseudomona Putida) and the PHA weight produced, the relationship we obtained is as follows:

$$ PHA = 0.2022 \cdot CellDryWeight $$

Where $ PHA $ and $ CellDryWeight $ are in grams ($ g $). The average for the prediction error is $\mu = 0.2008$ and the variance $\sigma^2 = 1.9005$. The coefficient of determination is $R^2 = 0.9374 (93.74\%)$.

The equation with all the data is represented below:

The red dots near the origin correspond to a batch fermented in a flask, the blue dots correspond to an assay with two fedbatches in a fermenter of 2 liters. The black line is the linear regression line obtained by the least squares' method.

C. elegans behavior

In order to understand the system as a whole, we started with the simplest case, so our first study is based on the behavior of a single worm, initially in the absence of chemoattractant and later adding it.

Our first approach consists in the study of a single worm in a surface without chemoattractant, under this condition it is observed that a C. elegans moves randomly, this is defined as a Random Walk.

Random Walk is the mathematical formalization of a trajectory that consists of taking successive random steps. We ran several simulations in Scilab and C++, in order to represent a single C. elegans moving this way in the absence of attractants.

Random walks are used to describe the trajectories of many motile animals and microorganisms. They are useful for both qualitative and quantitative descriptions of the behavior of such creatures. In our case a single C. elegans was simulated as a point: $(x_t, y_t)$

At each instant $t$ in the simulation, step length $l_t$ and direction $\theta_t$ the equations are the following:

$$l_t = \Delta t\;\nu_t$$

$$\theta_t = \theta_{t-1} + \Delta t \left(\frac{d\theta_t}{dt} + \delta\right) $$

Where $\Delta t$ is the duration of the time step, $\nu_t$ is the instantaneous speed, $\frac{d\theta_t}{dt}$ $(= \dot{\theta_t})$ is the instantaneous turning rate (using the convention that $\frac{d\theta_t}{dt}$$ > 0$ is a right turn and $\frac{d\theta_t}{dt}$$ < 0$ is a left turn) and $\delta$ is the turning bias.

The values of these variables were taken randomly from different gaussian distributions, that we identified by sampling but also obtained from some papers:

$\nu_t$: normal distribution with $\sigma = 0.0152\;cm/s$ and $\mu = 0.00702\;cm/s$

$\dot{\theta_t}$: normal distribution with $\sigma = 0.0150273\;rad/s$ and $\mu = 0.6789331\;rad/s$

$\delta$: normal distribution with $\sigma = 0.0076969\;rad/s$ and $\mu = 0.0370010\;rad/s$

Simulations were performed in Scilab and C++, proceeding as described in (Pierce-Shimomura et al., 1999). We contacted the authors but they could not provide us with the code, so we developed our own script based on the article, obtaining similar results:

You can also simulate C.elegans random walk in our Simuelegans online application

Simulated with our own software SimuElegans.

Please note that the actual movements of C. elegans are much slower and thus the simulation in this video is accelerated for convenience.

In these simulations we considered $\Delta t = 1\;s$, but actually we simulated it every $0.01\;s$, so its $\frac{1\;s}{0.01\;s} = 100$ times accelerated.

Chemotaxis of a single worm

However, we are interested in the movement of the nematode in a gradient of chemoattractant.

Studies revealed that the behavior of E. coli during chemotaxis is remarkably similar to the behavior of a single C. elegans in the presence of a chemotactic source (Bargmann, 2006), a mechanism called the pirouette model in C. elegans (Pierce-Shimomura et al., 1999) and the biased random walk in bacteria (Berg, 1993; Berg, 1975). The basis of these models is a strategy that uses a short-term memory of attractant concentration to decide whether to maintain the current direction of movement or to change to a new one.

Following this model, we defined the turning rate as a function of $\frac{\partial [C]}{\partial t}$. Where $[C]$ is the concentration ($[\;]$) of chemoattracant ($C$). Simulations were performed as expected, showing a bias in the random walk:

You can also simulate C.elegans chemotaxis in our Simuelegans online application

Simulated with our own software SimuElegans.

Chemotaxis of a single worm consuming attractant

As a last step of the study of a single worm, we decided to modelize the most realistic behavior. This behavior happens when, in addition to moving randomly but biased toward the gradient of chemoattractant, we consider the fact that it is constantly consuming its “food”, so these gradients will not be any more constants in time.

In order to implement this model, we realized that was impossible to study still considering the space as an attractant function, cause it changes its shape in every time step, and it made simulations really slow (maybe, days of computation). So, we meshed the space, and gave every point a different weight, depending on time: that was the starting of the matrix and approximated (numerical) calculations. What we obtained was close to have relevant impacts in the course of our project, because we could interfere in the C. elegans path, and not only in its final position, making it moving from one source of chemoattractant to another:

Simulated using Scilab

Note that this simulation has been speeded 600%.

Moreover, these numerical methods opened our eyes to study their movement as a whole, with partial differential equations.

Bargmann CI (2006) Chemosensation in C. elegans. Wormbook

Berg HC (1993) Random walks in biology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.

Pierce-Shimomura JT, Morse TM, Lockery SR (1999) The Fundamental Role of Pirouettes in C. elegans Chemotaxis. The journal of Neuroscience, 19(21):9557-9569

Group behavior

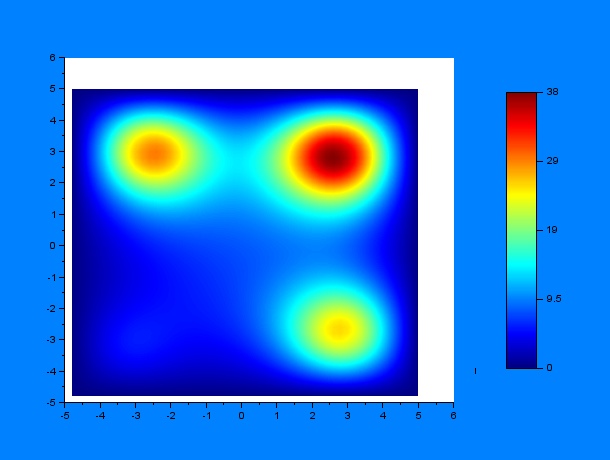

One of the 3D simulations performed in SciLab.

In practice, a single C. elegans is not employed to perform the task but a group of worms. In this case, the random walk equations obtained for a single worm behavior can be transformed into partial differential equations (PDEs), using Taylor series, to depict the distribution of the population, as the ones describing a diffusion process (![]() Click here for a mathematical proof of one dimensional diffusion process using PDEs from random walk)

Click here for a mathematical proof of one dimensional diffusion process using PDEs from random walk)

However, in our case we face a diffusion system with drift, in which the last term arises from the biased movement of C. elegans. To obtain a PDE that reflects this behavior, we employed difference equations also using Taylor series and apropiate limits (![]() Click here for a mathematical proof of two dimensional biased diffusion process (C. elegans chemotaxis behavior) using PDEs from biased random walk)

Click here for a mathematical proof of two dimensional biased diffusion process (C. elegans chemotaxis behavior) using PDEs from biased random walk)

The equation is the following:

$$\frac{\partial [C]}{\partial t} = D\;\nabla^2[C] - \nabla\cdot(\underline{\nu}\;[C]) $$

Once obtanied the equation that governs our system, we proceed to study if it works correctly for our purpose. However, analytical solutions for this equation are known for few ideal cases. For example, for a monodimensional bistable potential the stationary state is the following (Okopinska, 2002):

$$ P_{ss}=\mathscr{N}^{-1} e^{\left(-V(x)/D\right)}$$ where $ \mathscr{N} $ is the normalization constant.

As seen, our system, can theoretically work as expected, depending on the shape of the chemoattractant only. This is a great result because it shows our worms are capable of reaching each region.

Our final goal in this section is predicting the temporal and spatial behavior in 2D for non-ideal problems. In this case, using numerical methods is the only way to solve the system.

For the 2-dimensional case, $[C] = [C(x, y, t)]$ is the concentration of C. elegans at a given instant $t$ and at a given point $(x, y)$, $D$ is the diffusion coefficient and $\overrightarrow{\nu}$ is the attraction field for the C. elegans, which basically stands for its velocity. This expression naturally expands to: $$\frac{\partial [C]}{\partial t} = D \; \left(\frac{\partial^2 [C]}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 [C]}{\partial y^2}\right) - \left(\frac{\partial\nu_x}{dx}[C] + \nu_x\frac{\partial [C]}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial\nu_y}{dy}[C] + \nu_y\frac{\partial [C]}{\partial y}\right) $$

We first started by building up an explicit finite difference method, this is numerically fast but it is prone to instabilities in the solutions. Therefore, we decided to develop a Crank-Nicolson method which is unconditionally stable, thus being suitable to carry out parameter identification of a model. Nevertheless, it has the drawback of being numerically more intensive, because a set of algebraic equations must be solved in each iteration (![]() Click here for a mathematical explanation of the Crank-Nicolson method).

Click here for a mathematical explanation of the Crank-Nicolson method).

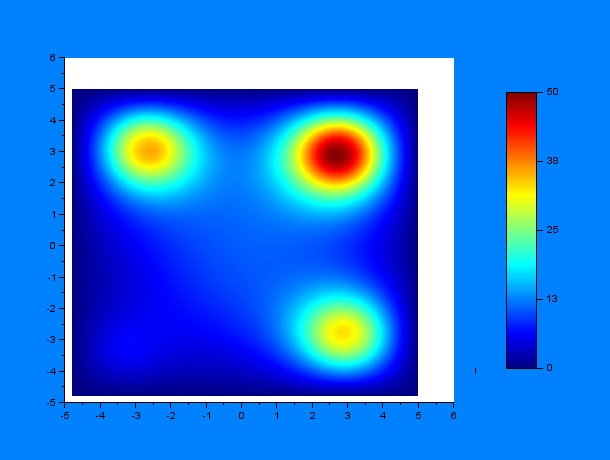

Now, we can predict the behavior of a set of worms in presence of a chemoatractant. One must have into account that the system may behave differently depending on some variables, for example, the diffusion coefficient $D$, a constant $k$ that determines the weight that the drift variable $\nu$ has and the time constants for the chemoattractant diffusion $t_1$ and $t_2$, where $t_1$ is the elapsed time since a first chemoattractant drop is put into the petri plate, $t_2$ stands for the elapsed time since a second drop of chemoattractant is put into the petri plate until a C.elegans initial distribution is added, the diffusion of chemoattractants is then assumed to be negligible for simplicity reasons. According to these parameters, we performed a lot of simulations using SciLab, what they all have in common is the position of the four chemotactic sources. The simulations were performed by first varying only $t_1$ and $t_2$ for some given $D$ and $k$ ($D = 0.2$ & $k = 0.001$):

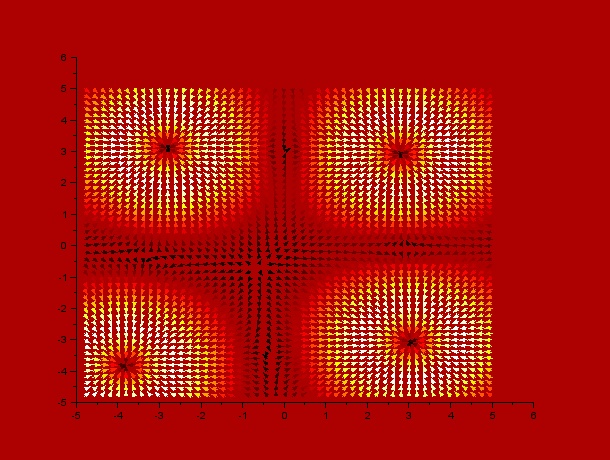

It can be observed by ploting the drift field for each case, that the final distribution is mostly dependent on the mentioned drift field, which in fact is mostly dependent on $t_1$ and $t_2$. Here we present the drift fields for each case:

Qualitatively, it can be seen through these simulations that incrementing $t_1$ or $t_2$ disperses and smoothes the drift field which actually affects the final distribution of C.elegans by dispersing it.

Videos corresponding to each simulation can also be seen here:

And then by varying only $D$ and $k$ (separately, of course) for some given $t_1$ and $t_2$ ($t_1 = 10$ hours & $t_2 = 12$ hours):

According to these results, qualitatively, higher values of $D$ or lower values of $k$ (and thus a greater $D/k$ relation) give a much more disperse distribution of C.elegans.

Videos corresponding to each simulation can be seen here:

We also carried out some simulations with different number of attractant sources. One can find simulations with $1$, $2$ and $3$ sources, and parameters $D\;=\;0.2$, $k\;=\;0.001$ (thus $D/k\;=\;200$) here:

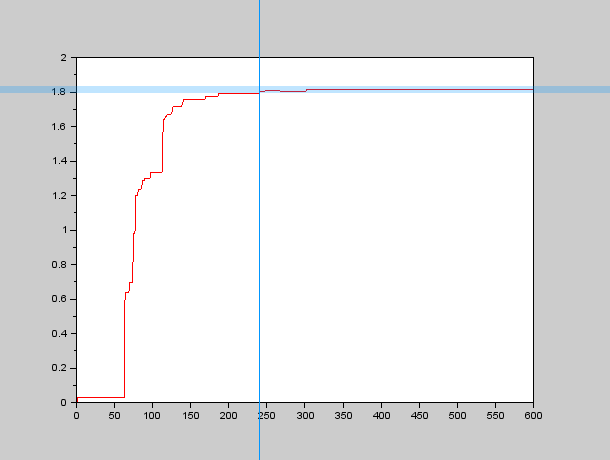

Parameter identification in PDEs is a rather complex topic, we did some research concerning our Group Behavior Model which is a Fokker-Planck Equation with a somewhat complex drift term $\nu$, which depends on position in our model (it could also depend on more factors which would add even more complexity to the system and therefore we didn't study them). We weren't lucky enough to find anything related to the topic (at least with the time we had), so we thought about implementing our own algorithms, based on an educated guess (As usual all the code we wrote can be found under the Software section). We wanted to study the spatial time constant of the system, that is, how long does it take for the system to reach an stable spatial distribution? We thought about a obtaining a variable $\mathcal{V}$ that would grow asimptotically after some time $\tau_{xy}$ (the spatial time constant). That is, our variable $\mathcal{V} \rightarrow C$ as $\tau_{xy} \rightarrow +\infty$. We then came up with the idea that local maxima would be a good way to define when the spatial distribution was stable, so we decided that the slower local maximum (that is the local maximum which is the slowest in stabilizing to its final position) would be a good approach to define the spatial time constant $\tau_{xy}$.

Therefore we needed an algorithm to calculate all the local maxima at a given instant and also to determine when they have "stopped" moving, so we programmed an approximate algorithm to find the local maxima in SciLab and used a more or less small band centered around the final value to determine $\tau_{xy}$. An example of the graphs we obtained through this process can be seen here:

So we carried out several simulations with different values for our parameters $D$ and $k$, in order to obtain the forementioned relationship between $D$, $k$ and $\tau_{xy}$.

First of all, we managed to plot and obtain the function that relates $D$ with $\tau_{xy}$, for $k=0.00025,\;0.0003,\;0.000375,\;0.0005$ and $0.001$. And as one can observe, different values of $k$ just move the curves but the main shape of the functionals remains the same, that is, exponential (with rather great coefficients of determination).

From the results we hypothesized that the general form of the functional (depending on $k$) was as follows:

$$D(\tau_{xy},k) = f(k)e^{\left(g(k)\tau_{xy}\right)}$$

We then plotted the coefficients $f(k)$ and $g(k)$ vs. $k$, as shown here:

We first obtained a quadratic regression and the resulting equations for $f(k)$ and $g(k)$ were:

$$f(k) = 3e6\;k^2 - 4658.1\;k+1.9523$$

$$g(k) = 6177.4\;k^2 - 11.907\;k-0.0013$$

But $R^2$ was about $80.17\%$ for $f(k)$, way too low, so then we decided to obtain a better model by using Lagrange's Interpolating Polynomials, which are represented by the green curves on the graphs above. Thus we obtained the following final equation for $D$:

$$D(\tau_{xy},k) = \left(-3.4061e13\;k^4+4.22776e10\;k^3+3.2955e6\;k^2-15277\;k+4.19004 \right)\;e^{\left(2.31802e11\;k^4-4.23644e8\;k^3+241467\;k^2-57.5001\;k+0.0008832 \right)\;\tau_{xy}}$$

From this the equation for $\tau_{xy}$ can be obtained:

$$\tau_{xy}(D,k) = \frac{1}{0.0008832 - 57.5001\; k + 241467\; k^2 - 4.23644e8\; k^3+2.31802e11\; k^4} log\left(\frac{D}{4.19004 - 15277\; k + 3.2955e6\; k^2 + 4.22776e10\; k^3 - 3.4061e13\; k^4}\right)$$

Where $D$ and $k$ are the mentioned parameters of the model and $\log$ refers to the natural logarithm (base $e$).

The average of the relative error is somewhat lower (at least in the studied region), about $8.00677\%$, compared to about $9.4\%$ for the first approximation.

From this equations we tried to obtain the parameters $D$ and $k$ for our model by stablishing a relationship that would not lead to dirac deltas in the final solution, which is what usually happened and is the theoretical solution provided the initial distribution of worms is also a dirac delta. Therefore we obtained the relationship $\frac{D}{k} = 502.2$ that would lead to a temporal stabilisation of the distribution, meaning no dirac deltas would arise. The intention was to provide our wetlab mates with theoretical data to improve their experiments and therefore creating a feedback loop in which they could provide data to us to improve our model even more and they would receive result back and so on. But, in fact, with the obtained relationship and our data we weren't able to find correct values for $D$ and $k$. We think this maybe due to the restricted region for $\tau_{xy}$, $D$ and $k$ that we studied. We also think that through the same process we would be able to achieve correct relationships for the variables in other regions of interests the problem is with increasingly small $D$ and $k$ parameters, come increasingly large times for the simulations to run and we weren't able to do so in our personal computers. This would therefore be a future task, to carry out more simulations maybe on a computer cluster with parallelization. We think that then the principles we followed would still hold.

Okopinska A. (2002) Fokker-Planck equation for bistable potential in the optimized expansion. Physical review E, Volume 65, 062101

System performance

All this modeling part was made to track a set of worms in a given soil. This can be used to compare our system, a non-stirred solid bioreactor, with a conventional stirred liquid bioreactor. Simple ODEs for bacterial growth and substrate consumpton are used in a cualitative fashion to determinate the industrial applications.

Modelling this part is difficult because there are a lot of factors involved. Therefore, asumptions must be made. Our first approach is the study of the stationary state in both systems: In a stirred bioreactor, the concentration of both bacteria and substrate are constant whereas in a non-stirred one exists a determinated distribution. For the concentration distribution in the non-stirred bioreactor is gaussian and the bacteria distribution (consecuence of the attraction of C. elegans for the substrate) is given by the stationary state distribution for an one-dimensional case.

The pictures are graphical examples of both situations: Stirred case (left) and non-stirred (rigth). Substrate is shown in purple, bacteria in blue, and the relation between them in grey. The total concentration is the area below the curve. Values are arbitrary.

As can be seen, a higher bacteria/concentration ratio is achieved in our system than the conventional one. Anyone can appreaciate that the ratio tends to one, being lower than the conventional case ratio, but in that region the substrate concentration is nearly zero. So it is not interesting to study.

But one question arises: Is this significant? In fact, it is not. In both cases, the average ratio in the non-stirred case is the same as the stirred one. But it is not a drawback. It means that our system can perform the same as a conventional bioreactor but with the advantages of a higher concentration. Therefore, the production yield in higher.

In general, our system behaves as well as a conventional one for the stationary, linear, ideal case. Particular cases are not studied because they have to be analyzed independently. A complex model can be developed for each case to study its viability for its practical use, but it needs more time. Because of that, we made a cualitative study for the system. While time is a problem (stirring is faster than nematode crawling), higher yields and better suitability for several problems are important advantages of our system. Also, the combination of our model and the tracking device helps to determinate the final result.

"

"