Team:Berkeley/Methods

From 2013.igem.org

| (35 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

<div id="navbar"> | <div id="navbar"> | ||

<ul class="nav"> | <ul class="nav"> | ||

| - | <li id="TitleID"> <a | + | <li id="TitleID"> <a id="TitleID" href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Berkeley/Methods">Methods</a> </li> |

| - | <li ><a href="#1"> | + | <li ><a href="#1">Degenerate Primer Design</a></li> |

| + | <li ><a href="#2">Plant total RNA Extraction</a></li> | ||

| + | <li ><a href="#3">cDNA Library Generation</a></li> | ||

| + | <li ><a href="#4">Determining Enzyme Kinetics</a></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 19: | Line 22: | ||

<div id = "Methods"> | <div id = "Methods"> | ||

| - | + | <div class = "heading-large"><a name="Undergraduates">Protocols</a></div> | |

| + | <p> Our team experimented with a number of interesting techniques during iGEM. Here, we enumerate some of them with added advice for future iGEM teams to use as a guide. </p> | ||

| + | <div id="1"><div class = "heading-large"><a name="#">Degenerate Primer Design</a></div> | ||

| + | <div style="margin: 0px 20px 20px 20px;"> | ||

| + | <h3>Purpose:</h3> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>When a particular protein sequence is known, but the codon usage per amino acid is not, designing primers that account for the codon degeneracy allows for PCR extraction of the given gene from a DNA template. This technique is especially useful when searching for a gene that has highly conserved regions in the amino acid sequence, such as actin, but may have different codon usage across the array of species in which the protein is found.</p> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | <p> | + | <p>In iGEM 2013 Berkeley’s project, identifying a B-glucosyltransferase that acts on indoxyl was key, as a sequence for an indoxyl-specific B-glucosyltransferase does not exist in literature. Furthermore, none of the genomes of the indigo producing plant species have been sequenced, making our task even more difficult. By taking advantage of conservation patterns among B-glucosyltransferases from sequenced plant species related to indigo producing plants, we were able to design degenerate primers aimed to enrich cDNA libraries of the indigo plants for B-glucosyltransferases.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Materials:</h3> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> 1. DNA sequence editor (ApE) </li> | ||

| + | <li> 2. Protein database (UniProt, NCBI) </li> | ||

| + | <li> 3. BLASTX, PBLAST </li> | ||

| + | <li> 4. Access to an Oligo synthesis facility </li> | ||

| + | <li> 5. Sequence alignment software (Clustal Omega) </li> | ||

| + | <li> 6. JalView 2.0 or other multiple sequences alignment viewer </li> | ||

| + | <li> 7. Primer design software to ensure stability of designed primers </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Method:</h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>1. Identify gene of interest </b> | ||

| + | <p> • In our case, we did not have access to the sequence of our protein of interest. So we relied on the information available for the general family of B-glucosyltransferases into which our desired enzyme falls. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>2. Gather protein sequences of homologous genes to gene of interest </b> | ||

| + | <p> • We first identified the taxonomic group that includes sequenced plant species and our indigo producing plants. This taxonomic group was the “core eudicotylions.” We then identified B-glucosyltransferases from sequenced plant species that have been characterized to act on substrates similar to indoxyl, and entered these protein sequences into the BLAST local alignment tool. This tool allows users to gather other related proteins with high sequence similarity to the query. After performing several iterations of searches like these using a variety of B-glucosyltransferases, we assembled our 200 sequences into a single document in FASTA format. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>3. Generate multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of gathered homologs </b> | ||

| + | <p> • Using a downloadable alignment tool such as MAFFT or ClustalΩ allows the user to generate an MSA from the gathered sequences. An MSA indicates the degree of conservation among the selected homologs, with dashes showing no conservation. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>4. Use MSA editor/viewer to visualize and interpret MSA </b> | ||

| + | <p> • Jalview 2.0 was used by our team to visualize the B-glucosyltransferase MSA. To easily identify conserved regions, a coloring scheme based on percent identity was applied, which showed highly conserved regions in dark blue. In the set of B-glucosyltransferases we gathered, a highly conserved region of 7 amino acids was identified. Further research into this region showed that it is referred to as the PSPG box, a sequence of amino acids that allow the enzyme to recognize UDP-glucose, the donor substrate in our pathway. We decided to take advantage of this PSPG box and a similarly conserved region towards the beginning of the MSA to enrich cDNA libraries generated from a variety of indigo producing plants for B-glucosyltranferases. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/7/74/MSA.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>5. Design Primers based on codon degeneracy table and conserved region </b> | ||

| + | <p> • For the PSPG box, the conserved amino acids we decided to take advantage of were HCGWNS. Each amino acid has a different number of codons that can code it. For example, W, tryptophan, only has a single codon that codes for it while S, serine, has 6 codons that code for it. Serine can be coded by either an A or T in the first codon position, a C or G in the second, and either A, C, G, or T in the third. This gives serine a total degeneracy of 16, indicating that there are 16 combinations of codons that must be generated in the primers to account for all different nucleotide combinations that can code serine. A simple way to represent the degenerate sequence for the serine codon is by writing WSN, where each letter corresponds to some subset of nucleotides. A complete list of degeneracies per amino acids and the corresponding single letter code for nucleotides is given. </p> | ||

| + | <p> • Choose the appropriate degenerate sequences for each amino acid that is conserved. Assemble these together and generate your degenerate primer! Ensure that the melting temperatures of the forward and reverse primers to be used in a single PCR are similar. The final primers we designed for the PSPG box are shown below. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="width:70%; margin:0 auto;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/df/PSPG_Box_Primer.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>Other Design Considerations</b> | ||

| + | <p> • To ensure that the overall concentration of primers is sufficiently high, primers with 128-fold degeneracy or less are recommended by Springer protocols. The complete degeneracy of the primer is obtained by multiplying together the degeneracy of each amino acid in the designed sequence. </p> | ||

| + | <p> • The primer should be 20-23 nucleotides long to ensure annealing. </p> | ||

| + | <p> • The gene of interest to be extracted should be between 200-1000 bps long to ensure that short PCR fragments do not dominate. </p> | ||

| + | <p> • If degeneracy is too high, using multiple sets of primers that have slightly less degeneracy could provide better results. </p> | ||

| + | <p> • If using a eukaryotic cDNA library as a template for PCR, taking advantage of the 5’ poly-T tail for PCR may prove useful. As long as a fraction of the gene is extracted, sequencing and further primer design could eventually extract the full gene. If using a 5’ RNA addition while generating a cDNA library, oligos for the 5’ addition could also be used for PCR. </p> | ||

| + | <p> • Using inosine (I) as a substitute for N or H nucleotides could reduce degeneracy between 2-4 fold. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/11/Degenerate_Primer_Table.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8d/Degenerate_Primer_Table_2.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>Design Protocol Adapted From Springer Protocols:</b> | ||

| + | <p>The design protocol from Springer can be found <a href="http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/917/chp%253A10.1007%252F978-1-61779-228-1_14.pdf?auth66=1383077314_7f47aa72588928dfc35b14f42a0ae56f&ext=.pdf">here</a>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="2"><div class = "heading-large"><a name="#">Plant Total RNA Extraction</a></div> | ||

| + | <div style="margin: 0px 20px 20px 20px;"> | ||

| + | <h3>Purpose:</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Using mRNA from plants as template for gene extraction helps avoid the complexity of intron/exon splicing mechanisms common in plants. In order to take advantage of this, we extracted total RNA from four indigo producing plants. Unlike the genome, the transcriptome (all the RNA transcripts) is a variable set. Types of transcripts and concentrations are dependent on the age of the plant, tissue type, and even time of the day. We decided to collect young leaf tissue based on literature reports of increased RNA yields in this phase of plant development and reports that B-glucosyltransferases are found in the leaves. </p> | ||

| - | < | + | <div style="width:70%; height:300px; float: left;"> |

| + | <h3>Materials:</h3> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> 1. Live plant or flash frozen leaves </li> | ||

| + | <li> 2. Liquid N<sub>2</sub> </li> | ||

| + | <li> 3. 2ml Corning Cryo Vial (Flat bottom) </li> | ||

| + | <li> 4. Metal bead </li> | ||

| + | <li> 5. RNeasy Plant Kit – Qiagen. </li> | ||

| + | <li> 6. QIA-Shredder Columns – Qiagen. </li> | ||

| + | <li> 7. RNAse free pipet tips, and Eppendorf tubes. </li> | ||

| + | <li> 8. 200-proof EtOH </li> | ||

| + | <li> 9. Beta-mercaptoethanol. </li> | ||

| + | <li> 10. Ball-Mill Shaker or Vortexer. </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="width:30%; height:300px; float: left;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/a/ab/RNA-Extraction-Materials-1.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Things to consider:</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Since RNA is the least stable of the nucleic acids, it is important to be particularly careful while following this procedure. One of the main reasons of RNA instability is the ubiquitous presence of RNAse, an RNA degrading enzyme. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>RNAse is particularly resilient, and has very fast activity. Many companies sell materials that help inhibit RNAse activity such as RNAseZAP (Sigma-Aldrich) and RNAseOut (Life Technologies). These materials are useful in preventing RNAse that exist in the environment, but have little effect on RNAse already present in your sample. Your best friends when working with RNA will be temperature and time. To prevent degradation, it is important that your sample remains frozen and that you work fast. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="width:85%; height: 320px; float: left;"> | ||

| + | <h3>Plant RNA extraction protocol (Adapted from Plant RNeasy Kit Protocol):</h3> | ||

| + | <p> 1. Use RNAseZAP or similar product to remove RNAses from working environment.</p> | ||

| + | <p> 2. Add a metal bead to pulverize plant tissue to 2ml Corning Cryo Vial. </p> | ||

| + | <p> 3. Obtain ~30mg of plant tissue, add it to the vial, and flash freeze the entire vial in Liquid N<sub>2</sub>. </p> | ||

| + | <p> a. Note that once the tissue is removed from the plant, it will begin degrading immediately. Careful handling of the tissue, and prompt freezing are of the essence. </p> | ||

| + | <p> b. Allow Liquid N<sub>2</sub> to enter the vial and be in direct contact with the tissue. Let the Liquid N<sub>2</sub> evaporate before sealing the vial. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="width:15%; height: 320px; float: left;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/03/RNA-Extraction-Materials-2.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> 4. Use a Ball-Mill shaker or a vortexer to grind the plant material to a fine powder. (Alternatively, a mortar and pestle may be used). </p> | ||

| + | <p> a. Do not allow the tissue to thaw. </p> | ||

| + | <p><b> The next steps should be carried out as quickly as possible</b><p> | ||

| + | <p> 5. Add 450ul of RTE+B-mercaptoethanol from RNeasy kit.</p> | ||

| + | <p> 6. Vortex 20 sec, then shake vial to bring all materials to the bottom (Repeat 5 times). </p> | ||

| + | <p> a. Everything in the tube should be liquid at the end of this step. BME is meant to prevent RNAse activity. </p> | ||

| + | <p> 7. Load sample into QIA-Shredder column (Obtained from Qiagen). Follow QIA-Shredder column protocol. </p> | ||

| + | <p> a. When removing sample from centrifuge, be sure to not to disturb the pellet.</p> | ||

| + | <p> 8. Transfer 400ul of supernatant to an Eppendorf tube.</p> | ||

| + | <p> 9. Add 200ul of pure EtOH – Pipete Up/Down to mix. </p> | ||

| + | <p> 10. Immediately transfer 600ul to RNeasy column. </p> | ||

| + | <p> 11. Follow Qiagen RNeasy <a href="http://www.qiagen.com/products/catalog/sample-technologies/rna-sample-technologies/total-rna/rneasy-plant-mini-kit#resources">protocol</a>.</p> | ||

| + | <p> 12. Elute with 30ul of RNAse free (DEPC treated) water.</p> | ||

| + | <p> a. Use eluted product to elute again from same column.</p> | ||

| + | <p> b. Freeze immediately and store at -80C. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>Final remarks</b> | ||

| + | <p>Concentration can be checked by Nano-Drop or RNA-Chip bioanalyzer (Agilent). Concentrations of 500ug/ul and above are ideal for most applications. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="3"><div class = "heading-large"><a name="#">cDNA Library Generation</a></div> | ||

| + | <div style="margin: 0px 20px 20px 20px;"> | ||

| + | <h3>Purpose:</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Due to the instability of RNA, generation of cDNA is ideal for the study of your transcriptome of interest. The type of cDNA library will be dependent on the downstream applications that you need. If you know the DNA sequence of your gene of interest, then a simple reverse transcription reaction will suffice. Reverse transcription relies on the existence of the Poly(A) tail of eukaryotic mRNA. Similar to PCR, reverse transcription uses a primer that binds the Poly(A), and a polymerase enzyme.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="width:70%; margin:0 auto;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d3/Mature_mRNA.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>If you don’t know the DNA sequence of your coding region, then a known sequence at the 5’end is necessary for full amplification. For the BlueGenes iGEM project, we are searching for a glucosyltransferase of unknown sequence. Here, we describe the generation of a cDNA library for the purpose of screening it with <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Berkeley/Methods#1">degenerate primers</a>.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Materials:</h3> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> 1. mRNA extracted from plant tissue (Concentration above 500ug/ul is ideal) </li> | ||

| + | <li> 2. GeneRacer<sup>TM</sup> Kit (Life Technologies) </li> | ||

| + | <li> 3. SuperScript III RT module – GeneRacer<sup>TM</sup> </li> | ||

| + | <li> 4. Mini centrifuge with temperature control (4C) </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Since RNA is the least stable of the nucleic acids, it is important to be particularly careful while following this procedure. Your best friends when working with RNA will be temperature and time. To prevent degradation, it is important that your sample remains cold, and that you work fast. In addition, maintain general sterile technique and use RNAse free materials. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Methods:</h3> | ||

| + | <p>GeneRacer<sup>TM</sup> contains protocols to dephosphorylate RNA, de-cap RNA, and ligate an RNA oligo to the 5’ end. We deviated only slightly from the protocols published by Life Technologies. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>1. Note that the diagram below suggests a 2 Day process. We obtained better results when following the entire protocol without stopping (Unfortunately, this resulted in spending the night in the laboratory). The entire process takes about 10-12 hours from RNA extraction to cDNA.</p> | ||

| + | <p>2. Due to the lack of sequence data for our coding region. We followed the 5’Race protocol (which includes the addition of an RNA oligo to the 5’ end), but performed a reverse transcription reaction with the use of the Poly(A) binding GeneRacer primer.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="width:60%; margin:0 auto;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/e4/Invitrogen_RACE-kit-13.png"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>General Suggestions</b> | ||

| + | <p>1. Controlling for genomic contamination can be carried out by simple PCR of a known gene that contains introns. The difference in size of gel bands will demonstrate if amplification happened from a mature mRNA or some other nucleic acid contamination. </p> | ||

| + | <p>2. The kit contains HeLa mRNA, which serves as a control for the successful generation of cDNA. Note that their actin primers are generally good to test other tissues, but creating your own control primers (from a known gene of the organism) provides an added degree of confidence. </p> | ||

| + | <p>3. cDNA will usually be too concentrated at the end of the protocol. Check the specifications of your favorite PCR protocols for ideal concentrations. </p> | ||

| + | <p>4. Remember that cDNA is a single stranded nucleic acid, which can form stable secondary structures. Use of DMSO, and hot-start PCR generally gave us better amplification results. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="4"><div class = "heading-large"><a name="#">Determining Enzyme Kinetics</a></div> | ||

| + | <div style="margin: 0px 20px 20px 20px;"> | ||

| + | <h3>Purpose:</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The Berkeley iGEM team 2013 has determined the enzyme kinetics of FMO and GLU (data for: <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Berkeley/Project/FMO#4" _target="new">FMO</a> and <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Berkeley/Project/GLU#3" _target="new">GLU</a>) based on the Michaelis-Menten kinetics model. Our purpose of determining kinetics was to give a quantitative data of how fast these enzymes can turnover their respective substrates, which is very useful when considering scaling up the process and for future iGEM teams when they use our enzymes. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Materials:</h3> | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li>Purified Enzyme: FMO or GLU </li> | <li>Purified Enzyme: FMO or GLU </li> | ||

| Line 36: | Line 208: | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| - | < | + | <h3>Methods:</h3> |

<b>1. Determining the Concentration of Purified Enzyme</b> | <b>1. Determining the Concentration of Purified Enzyme</b> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>We followed the protocol from <a href=” http://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/4110065A.pdf” _target=”new”>Bio-Rad’s Bradford Assay</a> to determine the concentration of purified FMO and GLU.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <div style="width:60%; margin:0 auto;"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/c/c7/Bradford_Assay.jpg"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<p>We determined the concentration of our purified enzyme to be 4.2 mg/L for FMO and 3.5 mg/L for GLU.</p> | <p>We determined the concentration of our purified enzyme to be 4.2 mg/L for FMO and 3.5 mg/L for GLU.</p> | ||

| Line 44: | Line 220: | ||

<b>2. Determining the Michaelis Menten kinetics </b> | <b>2. Determining the Michaelis Menten kinetics </b> | ||

| - | <div style=" | + | <div style="width:80%; margin:0 auto;"> |

| - | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/7/7c/Kinetics_Model.png"> | |

</div> | </div> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| - | + | <b>IMPORTANT</b>: We assumed that the oxidation step from indoxyl to indigo is much faster than the formation of indoxyl via FMO (indole to indoxyl) or GLU (indican to indoxyl). | |

</p> | </p> | ||

| - | |||

| + | <p>1. <b>FMO:</b> In each well of the TECAN plate, we added 0.3 mM of NADPH, purified FMO and various indole concentrations (0, 0.35, 0.50, 0.71, 1.02, 1.46, 2.09, 2.99, 4.27 mM) at 5% DMSO. </p> | ||

| + | <p>Note: The 5% DMSO originates from the fact that indole had to be dissolved in DMSO. We recommend minimal DMSO because FMO is sensitive to DMSO.</p> | ||

| + | <p>1. <b>GLU:</b> In each well of the TECAN plate, we added purified GLU and various indican concentrations (0, 0.10, 0.19, 0.39, 0.78, 1.55, 3.10, 6.20, 12.40 mM) dissolved in water.</p> | ||

| + | <p>2. Using a TECAN plate reader, we determined the absorbance at 620 nm (peak wavelength at which indigo absorbs) every minute for 50 minutes. </p> | ||

| + | <p>3. The absorbance data was converted into concentration of indigo based on the indigo standard we have determined previously. </p> | ||

| + | <p>4. We wrote a MATLAB code to automate analysis and generated the Michaelis-Menten Km.</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <br></div> | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</body> | </body> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <script> | ||

| + | var offset = 54; | ||

| + | $('#navbar li a').click(function(event) { | ||

| + | if ( ($(this).attr('id')) == 'TitleID') { | ||

| + | return; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | else { | ||

| + | event.preventDefault(); | ||

| + | $($(this).attr('href'))[0].scrollIntoView(); | ||

| + | scrollBy(0, -offset); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | }); | ||

| + | </script> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:39, 29 October 2013

Our team experimented with a number of interesting techniques during iGEM. Here, we enumerate some of them with added advice for future iGEM teams to use as a guide.

Purpose:

When a particular protein sequence is known, but the codon usage per amino acid is not, designing primers that account for the codon degeneracy allows for PCR extraction of the given gene from a DNA template. This technique is especially useful when searching for a gene that has highly conserved regions in the amino acid sequence, such as actin, but may have different codon usage across the array of species in which the protein is found.

In iGEM 2013 Berkeley’s project, identifying a B-glucosyltransferase that acts on indoxyl was key, as a sequence for an indoxyl-specific B-glucosyltransferase does not exist in literature. Furthermore, none of the genomes of the indigo producing plant species have been sequenced, making our task even more difficult. By taking advantage of conservation patterns among B-glucosyltransferases from sequenced plant species related to indigo producing plants, we were able to design degenerate primers aimed to enrich cDNA libraries of the indigo plants for B-glucosyltransferases.

Materials:

- 1. DNA sequence editor (ApE)

- 2. Protein database (UniProt, NCBI)

- 3. BLASTX, PBLAST

- 4. Access to an Oligo synthesis facility

- 5. Sequence alignment software (Clustal Omega)

- 6. JalView 2.0 or other multiple sequences alignment viewer

- 7. Primer design software to ensure stability of designed primers

Method:

1. Identify gene of interest• In our case, we did not have access to the sequence of our protein of interest. So we relied on the information available for the general family of B-glucosyltransferases into which our desired enzyme falls.

2. Gather protein sequences of homologous genes to gene of interest• We first identified the taxonomic group that includes sequenced plant species and our indigo producing plants. This taxonomic group was the “core eudicotylions.” We then identified B-glucosyltransferases from sequenced plant species that have been characterized to act on substrates similar to indoxyl, and entered these protein sequences into the BLAST local alignment tool. This tool allows users to gather other related proteins with high sequence similarity to the query. After performing several iterations of searches like these using a variety of B-glucosyltransferases, we assembled our 200 sequences into a single document in FASTA format.

3. Generate multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of gathered homologs• Using a downloadable alignment tool such as MAFFT or ClustalΩ allows the user to generate an MSA from the gathered sequences. An MSA indicates the degree of conservation among the selected homologs, with dashes showing no conservation.

4. Use MSA editor/viewer to visualize and interpret MSA• Jalview 2.0 was used by our team to visualize the B-glucosyltransferase MSA. To easily identify conserved regions, a coloring scheme based on percent identity was applied, which showed highly conserved regions in dark blue. In the set of B-glucosyltransferases we gathered, a highly conserved region of 7 amino acids was identified. Further research into this region showed that it is referred to as the PSPG box, a sequence of amino acids that allow the enzyme to recognize UDP-glucose, the donor substrate in our pathway. We decided to take advantage of this PSPG box and a similarly conserved region towards the beginning of the MSA to enrich cDNA libraries generated from a variety of indigo producing plants for B-glucosyltranferases.

• For the PSPG box, the conserved amino acids we decided to take advantage of were HCGWNS. Each amino acid has a different number of codons that can code it. For example, W, tryptophan, only has a single codon that codes for it while S, serine, has 6 codons that code for it. Serine can be coded by either an A or T in the first codon position, a C or G in the second, and either A, C, G, or T in the third. This gives serine a total degeneracy of 16, indicating that there are 16 combinations of codons that must be generated in the primers to account for all different nucleotide combinations that can code serine. A simple way to represent the degenerate sequence for the serine codon is by writing WSN, where each letter corresponds to some subset of nucleotides. A complete list of degeneracies per amino acids and the corresponding single letter code for nucleotides is given.

• Choose the appropriate degenerate sequences for each amino acid that is conserved. Assemble these together and generate your degenerate primer! Ensure that the melting temperatures of the forward and reverse primers to be used in a single PCR are similar. The final primers we designed for the PSPG box are shown below.

• To ensure that the overall concentration of primers is sufficiently high, primers with 128-fold degeneracy or less are recommended by Springer protocols. The complete degeneracy of the primer is obtained by multiplying together the degeneracy of each amino acid in the designed sequence.

• The primer should be 20-23 nucleotides long to ensure annealing.

• The gene of interest to be extracted should be between 200-1000 bps long to ensure that short PCR fragments do not dominate.

• If degeneracy is too high, using multiple sets of primers that have slightly less degeneracy could provide better results.

• If using a eukaryotic cDNA library as a template for PCR, taking advantage of the 5’ poly-T tail for PCR may prove useful. As long as a fraction of the gene is extracted, sequencing and further primer design could eventually extract the full gene. If using a 5’ RNA addition while generating a cDNA library, oligos for the 5’ addition could also be used for PCR.

• Using inosine (I) as a substitute for N or H nucleotides could reduce degeneracy between 2-4 fold.

The design protocol from Springer can be found here.

Purpose:

Using mRNA from plants as template for gene extraction helps avoid the complexity of intron/exon splicing mechanisms common in plants. In order to take advantage of this, we extracted total RNA from four indigo producing plants. Unlike the genome, the transcriptome (all the RNA transcripts) is a variable set. Types of transcripts and concentrations are dependent on the age of the plant, tissue type, and even time of the day. We decided to collect young leaf tissue based on literature reports of increased RNA yields in this phase of plant development and reports that B-glucosyltransferases are found in the leaves.

Materials:

- 1. Live plant or flash frozen leaves

- 2. Liquid N2

- 3. 2ml Corning Cryo Vial (Flat bottom)

- 4. Metal bead

- 5. RNeasy Plant Kit – Qiagen.

- 6. QIA-Shredder Columns – Qiagen.

- 7. RNAse free pipet tips, and Eppendorf tubes.

- 8. 200-proof EtOH

- 9. Beta-mercaptoethanol.

- 10. Ball-Mill Shaker or Vortexer.

Things to consider:

Since RNA is the least stable of the nucleic acids, it is important to be particularly careful while following this procedure. One of the main reasons of RNA instability is the ubiquitous presence of RNAse, an RNA degrading enzyme.

RNAse is particularly resilient, and has very fast activity. Many companies sell materials that help inhibit RNAse activity such as RNAseZAP (Sigma-Aldrich) and RNAseOut (Life Technologies). These materials are useful in preventing RNAse that exist in the environment, but have little effect on RNAse already present in your sample. Your best friends when working with RNA will be temperature and time. To prevent degradation, it is important that your sample remains frozen and that you work fast.

Plant RNA extraction protocol (Adapted from Plant RNeasy Kit Protocol):

1. Use RNAseZAP or similar product to remove RNAses from working environment.

2. Add a metal bead to pulverize plant tissue to 2ml Corning Cryo Vial.

3. Obtain ~30mg of plant tissue, add it to the vial, and flash freeze the entire vial in Liquid N2.

a. Note that once the tissue is removed from the plant, it will begin degrading immediately. Careful handling of the tissue, and prompt freezing are of the essence.

b. Allow Liquid N2 to enter the vial and be in direct contact with the tissue. Let the Liquid N2 evaporate before sealing the vial.

4. Use a Ball-Mill shaker or a vortexer to grind the plant material to a fine powder. (Alternatively, a mortar and pestle may be used).

a. Do not allow the tissue to thaw.

The next steps should be carried out as quickly as possible

5. Add 450ul of RTE+B-mercaptoethanol from RNeasy kit.

6. Vortex 20 sec, then shake vial to bring all materials to the bottom (Repeat 5 times).

a. Everything in the tube should be liquid at the end of this step. BME is meant to prevent RNAse activity.

7. Load sample into QIA-Shredder column (Obtained from Qiagen). Follow QIA-Shredder column protocol.

a. When removing sample from centrifuge, be sure to not to disturb the pellet.

8. Transfer 400ul of supernatant to an Eppendorf tube.

9. Add 200ul of pure EtOH – Pipete Up/Down to mix.

10. Immediately transfer 600ul to RNeasy column.

11. Follow Qiagen RNeasy protocol.

12. Elute with 30ul of RNAse free (DEPC treated) water.

a. Use eluted product to elute again from same column.

b. Freeze immediately and store at -80C.

Final remarksConcentration can be checked by Nano-Drop or RNA-Chip bioanalyzer (Agilent). Concentrations of 500ug/ul and above are ideal for most applications.

Purpose:

Due to the instability of RNA, generation of cDNA is ideal for the study of your transcriptome of interest. The type of cDNA library will be dependent on the downstream applications that you need. If you know the DNA sequence of your gene of interest, then a simple reverse transcription reaction will suffice. Reverse transcription relies on the existence of the Poly(A) tail of eukaryotic mRNA. Similar to PCR, reverse transcription uses a primer that binds the Poly(A), and a polymerase enzyme.

If you don’t know the DNA sequence of your coding region, then a known sequence at the 5’end is necessary for full amplification. For the BlueGenes iGEM project, we are searching for a glucosyltransferase of unknown sequence. Here, we describe the generation of a cDNA library for the purpose of screening it with degenerate primers.

Materials:

- 1. mRNA extracted from plant tissue (Concentration above 500ug/ul is ideal)

- 2. GeneRacerTM Kit (Life Technologies)

- 3. SuperScript III RT module – GeneRacerTM

- 4. Mini centrifuge with temperature control (4C)

Since RNA is the least stable of the nucleic acids, it is important to be particularly careful while following this procedure. Your best friends when working with RNA will be temperature and time. To prevent degradation, it is important that your sample remains cold, and that you work fast. In addition, maintain general sterile technique and use RNAse free materials.

Methods:

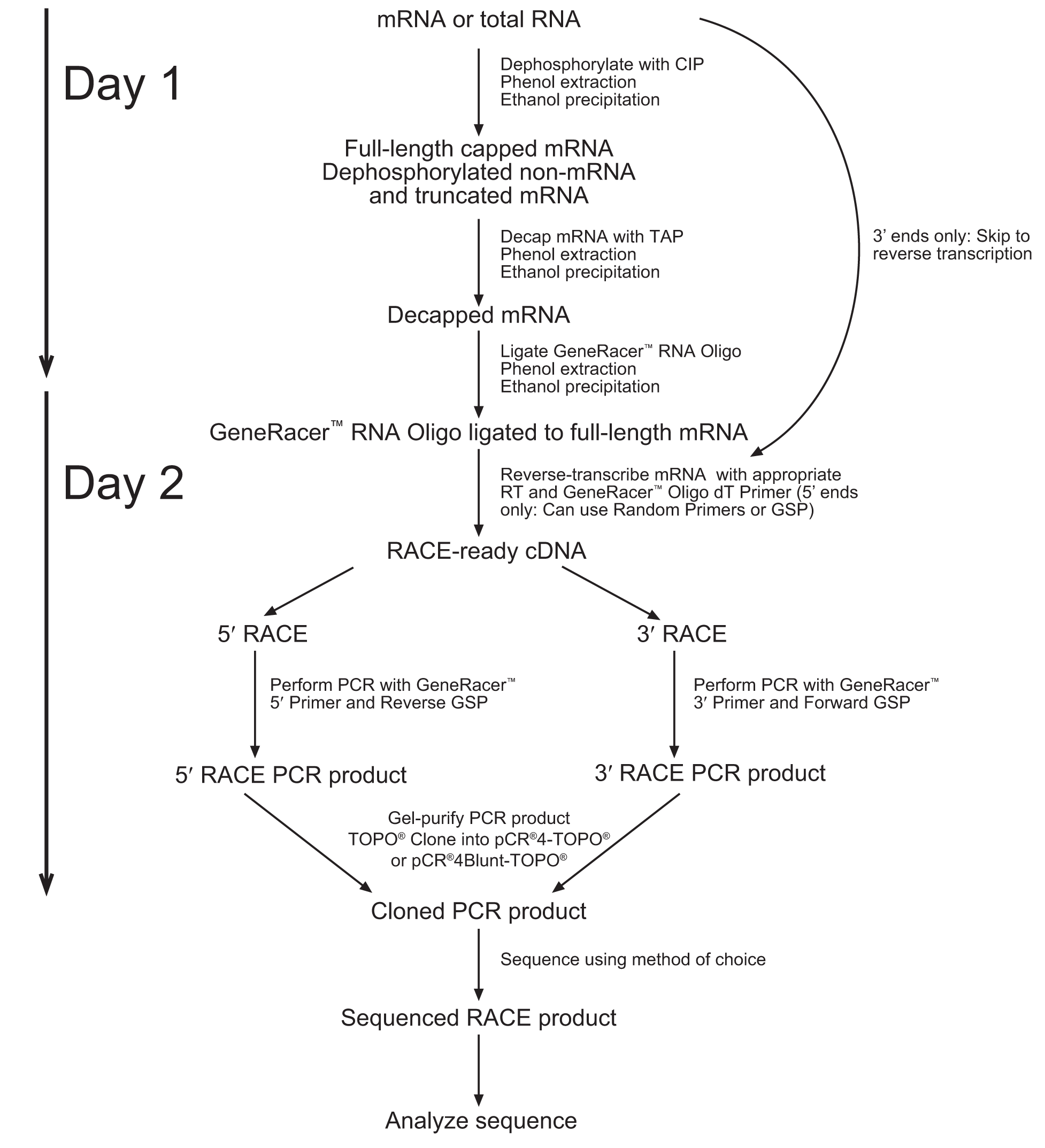

GeneRacerTM contains protocols to dephosphorylate RNA, de-cap RNA, and ligate an RNA oligo to the 5’ end. We deviated only slightly from the protocols published by Life Technologies.

1. Note that the diagram below suggests a 2 Day process. We obtained better results when following the entire protocol without stopping (Unfortunately, this resulted in spending the night in the laboratory). The entire process takes about 10-12 hours from RNA extraction to cDNA.

2. Due to the lack of sequence data for our coding region. We followed the 5’Race protocol (which includes the addition of an RNA oligo to the 5’ end), but performed a reverse transcription reaction with the use of the Poly(A) binding GeneRacer primer.

1. Controlling for genomic contamination can be carried out by simple PCR of a known gene that contains introns. The difference in size of gel bands will demonstrate if amplification happened from a mature mRNA or some other nucleic acid contamination.

2. The kit contains HeLa mRNA, which serves as a control for the successful generation of cDNA. Note that their actin primers are generally good to test other tissues, but creating your own control primers (from a known gene of the organism) provides an added degree of confidence.

3. cDNA will usually be too concentrated at the end of the protocol. Check the specifications of your favorite PCR protocols for ideal concentrations.

4. Remember that cDNA is a single stranded nucleic acid, which can form stable secondary structures. Use of DMSO, and hot-start PCR generally gave us better amplification results.

Purpose:

The Berkeley iGEM team 2013 has determined the enzyme kinetics of FMO and GLU (data for: FMO and GLU) based on the Michaelis-Menten kinetics model. Our purpose of determining kinetics was to give a quantitative data of how fast these enzymes can turnover their respective substrates, which is very useful when considering scaling up the process and for future iGEM teams when they use our enzymes.

Materials:

- Purified Enzyme: FMO or GLU

-

- Substrate:

- FMO: Indole, NADPH (co-factor)

- GLU: Indican

- TECAN Plate Reader and TECAN Plate

- Solvents: DMSO, Water

Methods:

1. Determining the Concentration of Purified EnzymeWe followed the protocol from Bio-Rad’s Bradford Assay to determine the concentration of purified FMO and GLU.

We determined the concentration of our purified enzyme to be 4.2 mg/L for FMO and 3.5 mg/L for GLU.

2. Determining the Michaelis Menten kinetics

IMPORTANT: We assumed that the oxidation step from indoxyl to indigo is much faster than the formation of indoxyl via FMO (indole to indoxyl) or GLU (indican to indoxyl).

1. FMO: In each well of the TECAN plate, we added 0.3 mM of NADPH, purified FMO and various indole concentrations (0, 0.35, 0.50, 0.71, 1.02, 1.46, 2.09, 2.99, 4.27 mM) at 5% DMSO.

Note: The 5% DMSO originates from the fact that indole had to be dissolved in DMSO. We recommend minimal DMSO because FMO is sensitive to DMSO.

1. GLU: In each well of the TECAN plate, we added purified GLU and various indican concentrations (0, 0.10, 0.19, 0.39, 0.78, 1.55, 3.10, 6.20, 12.40 mM) dissolved in water.

2. Using a TECAN plate reader, we determined the absorbance at 620 nm (peak wavelength at which indigo absorbs) every minute for 50 minutes.

3. The absorbance data was converted into concentration of indigo based on the indigo standard we have determined previously.

4. We wrote a MATLAB code to automate analysis and generated the Michaelis-Menten Km.

"

"