Team:Valencia Biocampus/Project

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 552: | Line 552: | ||

Otherwise, the medium for PHA production is tuned for the development of <i>Pseudomonas putida</i>, but not for the <i>E.coli</i>, so we had to test if | Otherwise, the medium for PHA production is tuned for the development of <i>Pseudomonas putida</i>, but not for the <i>E.coli</i>, so we had to test if | ||

this bacteria was able to grow in it. When we did this checking, we realized that the development of these bacteria did not occur in the PHA production | this bacteria was able to grow in it. When we did this checking, we realized that the development of these bacteria did not occur in the PHA production | ||

| - | media. However, with the addition of acetate (carbon source), the removal of the iron salt (added to the media to avoid the synthesis of a siderophore | + | media. However, with the addition of acetate (carbon source), the removal of the iron salt (added to the media to avoid the synthesis of a <span class="siderophore-tooltip">siderophore</span> by <i>Pseudomonas sp.</i>) and, due to serendipity, with the double |

concentration of trace elementes, we got the media for the enteric bacteria growth. | concentration of trace elementes, we got the media for the enteric bacteria growth. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| Line 566: | Line 566: | ||

emission of fluorescence due to the interaction between the Nile red and the PHA through an UV transilluminator <b>(Fig.5)</b>. By the results of the | emission of fluorescence due to the interaction between the Nile red and the PHA through an UV transilluminator <b>(Fig.5)</b>. By the results of the | ||

assays we chose to work with a <b>8mM</b> concentration of fatty acids (<b>Fig.4</b>). | assays we chose to work with a <b>8mM</b> concentration of fatty acids (<b>Fig.4</b>). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/dc/Vb_building_4.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | We also <b>checked the PHA production </b>by centrifuging the precultures, resuspending the pellet on PBS and adding Red Nile dissolved in DMSO, we could | ||

| + | see the emission of fluorescence due to the interaction between the Nile red and the PHA through an UV transilluminator <b>(Fig.5)</b>. By the results of | ||

| + | the assays we chose to work with a <b>8mM</b> concentration of fatty acids (<b>Fig.4</b>). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/c/c9/Vb_building_5.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | At this point we found that <i>E. coli </i>and <i>P. putida </i>could grow at 8mM of octanoic acid and that bioplastic (PHA) is also produced. However, | ||

| + | because <i>E. coli </i>grows better in <b>oleic acid </b>and we wanted to check if <b><i>P. putida </i></b>could produce PHA if its phaC operon was induced | ||

| + | by it, we grew both bacteria in <b>different concentrations of octanoic and oleic acid but maintaining a constant concentration of fatty acids of 8mM</b>. | ||

| + | The assays done are explained in the table below (<b>Fig.6</b>). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/6a/Vb_building_6.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | We saw that <i>E. coli </i>had grown better with the increasing of oleic acid, getting at its maximum on experiment 9, even so, the quantity of pellet | ||

| + | corresponding to 1 mL of preculture was scarce (and not visible at experiments 1 to 5). <i>E. coli </i>needed more time to grow in the PHA production | ||

| + | media. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <i>P. Putida</i> | ||

| + | had grown too, however we wanted to measure the production of bioplastic, we measured the ODs<sub>600</sub> from the precultures of <i>P. putida </i>by | ||

| + | centrifugating 2 mL of them and then washing them on 1 mL of PBS and resuspending the pellet in 500 μ<b>l </b>of PBS<b>. </b> Then, dilutions on PBS were | ||

| + | adjusted to the lowest OD<sub>600</sub><sub>,</sub>corresponding to the experiment number 9 (8mM oleic acid). The growth of <i>P. putida </i>lower in PHA | ||

| + | production media with a concentration of 8mM of oleic acid (<b>Fig. 7-8)</b>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/9/9c/Vb_building_7.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The results showed that the growth of <b><i>E. coli </i></b>on 8mM of oleic acid was better than in any other condition, then <b>experiment 9 </b> | ||

| + | conditions would be the best ones for the induction of <b>clumping. </b>However, even <b><i>P. putida </i></b>had produced bioplastic at all oleic acid | ||

| + | concentrations, the highest production levels corresponded to <b>experiment 1 </b>conditions, which means in absence of oleic acid, just on 8mM of octanoic | ||

| + | acid. Because of that, next assays were done following the conditions of <b>experiment 1 and 9</b> (<b>Fig.9</b>). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/2/2f/Vb_building_8.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | After the optimization of the media, kinetics of the production of PHA and biomass generation were realized in relation to the time (<b>Fig.10</b>). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8c/Vb_building_9.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <h3>Colonization assays</h3> | ||

| + | For establishing the right media, the one in which <i>E. coli </i>could be able to grow and induce clumping and <i>P. putida </i>produce PHA and get to a | ||

| + | balance<i> </i>between the two activities and for setting up some standard bases for doing an assay with the three microorganisms chosen for this synthetic | ||

| + | symbiosis that our team proposes, we made some colonization assays. Different ODs<sub>600</sub> of <i>E. coli </i>where plated in PHA production media in | ||

| + | the conditions of both <b>experiments 1 and 9 </b>(<b>Fig.6</b>). There were two sets of plates: | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | 1) PHA production media + 8mM oleic acid | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | 2) PHA production media + 8mM octanoic acid | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | In both of them (and their replicas) were plated the following <i>E. coli </i>ODs<sub>600 </sub>(<b>Fig.11</b>) and after let them grow for 48 hours, the | ||

| + | plates were divided into 4 parts in order to plate different <i>P. putida </i>ODs<sub>600 </sub>(<b>Fig.11</b>). The huge difference between the ODs chosen | ||

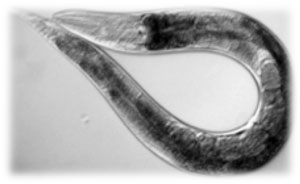

| + | for <i>E. coli </i>and <i>P. putida </i>was because we wanted to plate similar quantities of <i>the Pseudomonas </i>that <i>C. elegans </i>could afford to | ||

| + | carry, taking into account that the worm size is 1mm, approximately. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/18/Vb_building_10.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Then the production of bioplastic was seen by the fluorescence of the Nile red joined to the PHA (the samples were prepared as in <b>The right media</b>). | ||

| + | There were taken pictures of the plates but there was only growth of <i>Pseudomonas</i> in the first set of plates (PHA production media + 8mM oleic acid). | ||

| + | There was a notorious growth and production of bioplastic in the plates where <i>E. coli </i>was plated with an OD of 0,8 an 1,0 and the production of | ||

| + | bioplastic was higher at 0,03 and 0,05 OD<sub>600</sub> of <i>P. putida. </i>(<b>Fig.12</b>). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/a/a2/Vb_building_11.png" alt="" style="width:700px" /> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Revision as of 09:53, 4 October 2013

Project Overview

Why E.coli

Escherichia coli is a model organism widely use in fields as microbiology, molecular biology and genetics. Result of that is the great range of genetic manipulation techniques that can be found related to this Gram negative bacterium. There is also a lot of information about the biochemistry and genetics of this microorganism. All this allows to work easily with it in the lab and often perform assays testing different conditions that will be tried out in other organisms unstudied in such depth. Moreover, E.coli is the main food of C.elegans, organism that is able to incorporate nucleic acids from the bacteria, RNA, to its cells (Mello et al., 2004). This is the usual mechanism of transformation of the worm, introducing exogenous genetic material from the bacteria altering the expression of the worm’s genome in order to make modifications of interest.

Controlling the mechanism

The role of E.coli in our project is to carry out the synthesis of an iRNA for inducing the social feeding behavior of Caenorhabditis elegans , the clumping. To achieve this, we cloned the biobrick Bba_K1112000 in E. coli, XL1-Blue strain (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

- pSB1C3 is a high copy number plasmid (RFC [10]) carrying chloramphenicol resistance.

- The replication origin is a pUC19-derived pMB1 (copy number of 100-300 per cell).

- pSB1C3 has terminators bracketing its MCS which are designed to prevent transcription from *inside* the MCS from reading out into the vector. The efficiency of these terminators is known to be < 100%. Ideally we would construct a future set of terminators for bracketing a MCS that were 100% efficient in terminating both into and out of the MCS region.

This construction consists of the E.coli fadA promoter, which is activated in the presence of fatty acids (Clark, 1981), and the antisense sequence of the mRNA FLP-21 from C.elegans which encodes a protein involved in the solitary feeding behaviour of the worm, the formation of the dsRNA complex inhibits the expression of this protein, inducing the social feeding behavior (fig. 2).

Pseudomonas putida and PHA production

Pseudomonas putida is a gram-negative bacterium that is found in most soil and water habitats where there is oxygen. Its diverse metabolism and its capacity to break down organic harmful solvents (it has most genes involved in degrading aromatic or aliphatic hydrocarbons) in contaminated soils make this microorganism irreplaceable for research studies in the field of bioremediation but also for biosynthesis of value-added products. In addition, Pseudomonas putida has several strains including KT2440, the one we have worked with. This strain can colonize plant roots, from which they take nutrients, while at the same time it offers protection to the plant from pathogens.

For example, it is capable of converting styrene oil into the biodegradable plastic PHA. This helps to degrade the polystyrene foam which

was thought to be non-biodegradable. Styrene is a major environment toxic pollutant released from industrial sites. The conversion to PHA allows the cure

of styrene pollution but it is also beneficial to society because of its applications in tissue engineering.

PHA is also environmental friendly and has a long self-life therefore it is also used in everyday items. Unlike styrene, PHA can break down in soil or water.

Within Pseudomonas putida, PHA accumulates under unbalanced growth conditions as a means of intracellular storage, storing excess carbon and energy. These PHA polymers are synthesized by enzyme PHA synthase which is bound to the surface of the PHA granules and uses coenzyme A thioesters of hydroxyalkanoic acids as substrates.

The role of P. putida in the Synthetic symbiosis that we have designed is to be carried by C. elegans to hotspots of interest where would produce bioplastic PHA.

An overview about our nematode

One of the main characters of our work is a nematode known as Caenorhabditis elegans, from the Rhabditidae family. It was first used as an experimental model in Developmental Genetics studies and nowadays is also used in other fields such as Clinical Biology, Neurobiology and Cell Biology, being a good model to study Alzheimer disease, obesity, diabetes and aging, among others.

Another interesting thing is that it feeds on Escherichia coli. Its “favorite” strain is OP50, although we checked that it’s also able to feed on XL1-Blue strain, the one that we used in all our molecular biology experiments.

Some advantages of C. elegans when compared with other model organisms are:

- Lifespan ranges between 2 and 3 weeks, so experimentation times are reduced.

- Its maintenance and study is cheap and simple (it is transparent, which facilitates microscopic observation).

- It is very small (1 mm), so it is possible to carry out experiments with a huge number of worms in a small Petri dish having a great statistical support.

Why use C. elegans as a transport?

When we were considering on creating a new system for the transport of bacteria, we found different key advantages that made the nematode the best option. For example, C. elegans is able to move very fast around solid substrates (soil is, actually, its natural habitat) and also in agar, so it’s very useful for both lab experiments and real-environment tests.

Its movement, in addition to being very fast, has two modes: random and directed.

When there is no attractant in the medium, C. elegans moves doing uncoordinated movements in several directions in what is known as 'random walk'.

The situation changes when there is an attractant in the medium. Here, our 'transport' begins to direct his movements to the focus of the substance (volatile or soluble) which acts as an attractant in a process known as 'chemotaxis' thanks to the amazing smell of our nematode. This allows us to ‘guide’ the nematodes towards defined spots in irregular substrates.

Chemotaxis is the foundation to guide the transport of bacteria and is therefore the focus of experimentation with C. elegans, with the aim of finding the best attractant. This ability makes C. elegans a perfect 'bus' for bacteria. (simuelegans online here)

Moreover, we found two pathogens (Yersinia pestis and Xhenorhabus nematophila) with the ability to form biofilms on C. elegans thanks to the proteins of the operon hmsHFRS. When genetically-engineered strains of commonly used bacteria such as Escherichia coli or Pseudomonas putida express this hmsHFRS operon, they have the 'ticket' to travel: they are able to adhere to the worm’s surface by means of forming a synthetic biofilm.

Expanding our knowledge about C. elegans...

Once we knew that C. elegans was the best option, we began to discover interesting things for further study.

There are several strains of our nematode. The one that drew our attention was called 'N2', which had a fairly interesting behavior: under normal conditions, it eats individually, whereas under certain conditions (such as starvation), a social feeding behavior known as “clumping” is induced. But this phenomenon can also be induced if the expression of some particular genes is interfered. This fact gave us the opportunity to develop the first artificial symbiosis between worms and bacteria, based on the manipulation of the behaviour of C. elegans by simply nourishing it with transformed E.coli able to synthesize the iRNA.

With it, while C. elegans acts as transport, bacteria return the favour giving it the ability to eat in company.

Results

Parts

These are the BioBricks we have designed, constructed, and characterized. We have submitted them to the Registry of Standard Biological Parts

| Works? | Name | Type | Description | Designer | Length | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBa_K1112000 | Regulatory | fadB promoter + FLP-21 iRNA | Pedro Luis Dorado Morales | |||

| BBa_K1112001 | Regulatory | pGlnA + hmsHFRS operon | Alba Iglesias Vilches | |||

| BBa_K1112002 | DNA | Cluster PHA | Alba Iglesias Vilches |

BBa_K1112000: fadB promoter + FLP-21 iRNA

This construction is made up by a fatty acid-sensitive promoter that directs the transcription of an iRNA responsible for the social or solitary behavior of C.elegans.

BBa_K1112001: pGlnA + hmsHFRS operon

We reused our nitrogen sensitive promoter from one of our last year constructs and we employ it to control the expression on the operon that triggers the formation of a biofilm over C.elegans.

BBa_K1112002: cluster PHA

This BioBrick contains the complete natural sequence that induces the production of PHA in Pseudomonas putida (KT2440).

"

"