Team:Greensboro-Austin/Standard Proposal

From 2013.igem.org

Mhammerling (Talk | contribs) (→Conclusion) |

(→Introduction and Motivation) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

=Introduction and Motivation= | =Introduction and Motivation= | ||

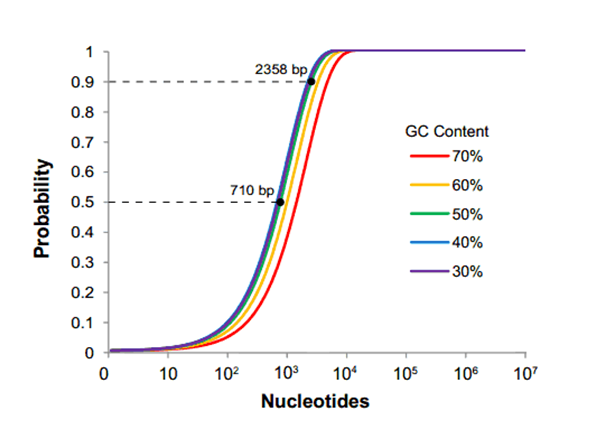

| - | As the field of Synthetic Biology emerged, arguments for | + | As the field of Synthetic Biology emerged, so did arguments for standardizing the assembly methods involved in constructing plasmids. The archetypical example of such standardization is BioBrick RFC[10], introduced in 2003 by Tom Knight at MIT. BioBricks are stored on a standard plasmid, pSB1C3, which contains prefix and suffix sequences flanking the part. These sequences contain two pairs of 6 bp restriction sites (EcoRI+XbaI and SpeI+PstI), which can be used for both part assembly and quality control. BioBricks are intended to be well-characterized biological parts, such as genes or promoters, that are predictable, ready to use, and can be combined in unique ways. The rules of this assembly method also require that none of these sites are present in the parts themselves. This requirement can be an onerous imposition for iGEM teams using large, novel parts such as genes and operons obtained from environmental samples. |

[[File:larry4.png|frame|left|500px|||Fig. 1: The probability of at least one restriction site appearing in a sequence. The length at which a sequence will have a 50% and 90% likelihood of containing a site are displayed for the 50% GC content line.]] | [[File:larry4.png|frame|left|500px|||Fig. 1: The probability of at least one restriction site appearing in a sequence. The length at which a sequence will have a 50% and 90% likelihood of containing a site are displayed for the 50% GC content line.]] | ||

Despite the problems with the current standard, it is clear that having a repository of genetic parts stored in a standard plasmid is useful to the field, especially for those with limited resources. Once these constructs are submitted into a database it is very easy for others to incorporate those parts into their own constructs because of the standardized submission; thus making collaboration much simpler. | Despite the problems with the current standard, it is clear that having a repository of genetic parts stored in a standard plasmid is useful to the field, especially for those with limited resources. Once these constructs are submitted into a database it is very easy for others to incorporate those parts into their own constructs because of the standardized submission; thus making collaboration much simpler. | ||

Revision as of 03:00, 28 September 2013

Introduction and Motivation

As the field of Synthetic Biology emerged, so did arguments for standardizing the assembly methods involved in constructing plasmids. The archetypical example of such standardization is BioBrick RFC[10], introduced in 2003 by Tom Knight at MIT. BioBricks are stored on a standard plasmid, pSB1C3, which contains prefix and suffix sequences flanking the part. These sequences contain two pairs of 6 bp restriction sites (EcoRI+XbaI and SpeI+PstI), which can be used for both part assembly and quality control. BioBricks are intended to be well-characterized biological parts, such as genes or promoters, that are predictable, ready to use, and can be combined in unique ways. The rules of this assembly method also require that none of these sites are present in the parts themselves. This requirement can be an onerous imposition for iGEM teams using large, novel parts such as genes and operons obtained from environmental samples.

Despite the problems with the current standard, it is clear that having a repository of genetic parts stored in a standard plasmid is useful to the field, especially for those with limited resources. Once these constructs are submitted into a database it is very easy for others to incorporate those parts into their own constructs because of the standardized submission; thus making collaboration much simpler.

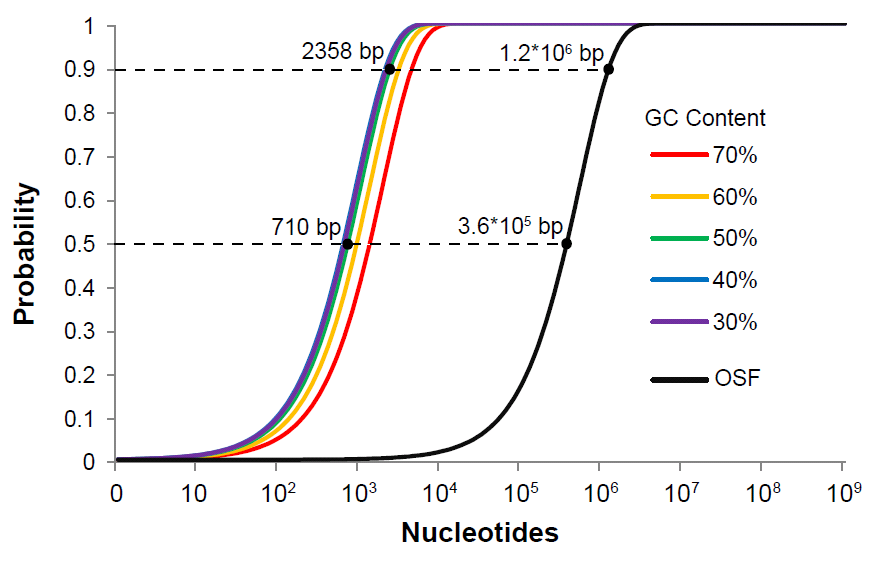

We concluded that the problem with RFC[10] lies in the fact that it requires everyone who wants to submit a part to the database to accommodate a highly restrictive assembly method. In an era when many fast, cheap, and scarless assembly methods are available, mandating a single assembly method no longer benefits the community. It is easily demonstrable that as the size of your construct increases toward the size of an average eukaryotic gene, the chance of one of the four restriction sites popping up in your sequence is rapidly surpasses 50%. We concluded from this analysis that restriction site mutagenesis likely burdens a majority of teams wishing to submit novel parts to the registry.

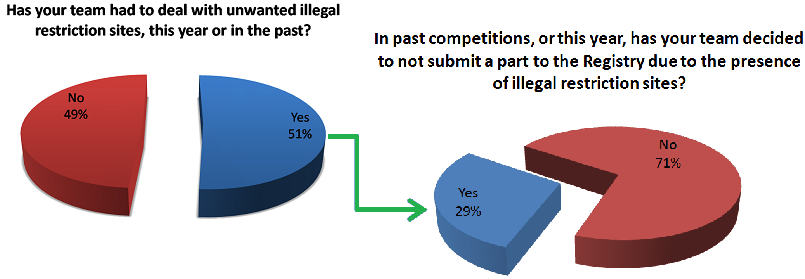

Survey Results

Fixing restriction sites requires both time and money because in order for anyone to utilize your part using the same standard you need to mutate away those unwanted restriction sites in your construct. For iGEM teams who have both limited time and funding, this is a real problem and nonetheless an obstacle for any research group trying to share their work using the Biobrick database. Furthermore, it draws resources away from better characterization of parts - a well-known deficiency of constructs submitted to the registry. Due to these major drawbacks, we speculated that other teams might be having the same issues with regards to part submission and illegal restriction sites. To find out we made a survey asking other teams if they ever come across the same sorts of problems as our team. This survey was distributed through emails to all faculty member emails found for iGEM teams, and through social media to contact student team members. As 9/27/13, we have received responses from 43 teams.

Notable Responses

Many of our respondents experienced difficulties with unwanted restriction sites in their parts, which results in fewer parts entering the the registry each year. However, some respondents were hesitant or even hostile towards the idea of changing the standard. Some notable responses from individuals at other institutions are shown below.

"I strongly agree with this statement. Having to perform site-directed mutagenesis in order to submit parts to the Registry is a complete waste of time"

Student

"Comment: the intent of the assembly standard is to lower the technical barrier for synthetic biology, not to prevent teams from getting awards. The repository is a collection of *sharable*, ready-to-use parts, not just a storage space for Team X's project. " Faculty Instructor

"We need to train our students on the way science is being done now, not back in 1980." Faculty Instructor

"If you have problems with cloning or the presence of 'illegal' restriction sites, stop complaining and deal with it." Graduate Advisor

"We started our experiments using restriction-ligation but all of these failed. Next we tried Gibson assembly and were almost immediately successful" Student

"While the current standard is archaic, movement to a new standard cannot commence without an analysis of the availability of the newest assembly kits/mechanisms, to all teams. The financial status of each team is far from equitable, and some kits can be quite expensive." Student

"Taking into account the dropping costs of chemical synthesis of DNA, molecular cloning will not be used for biotechnological purposes in a couple of years. Biobrick-based molecular cloning is obsolete." Faculty Instructor

"The biobrick R10 standard is restrictive and becomes more and more cumbersome if more than 1-2 forbidden restriction sites are present... However, I am concerned that if the standard was not available the registry might not be able to maintain and produce biobricks as easily as it can now." Student

"I agree that current "one pot" assembly methods and DNA synthesis are making the previous standard assembly methods obsolete. That said, what standard - if any - do you propose as a replacement? Does the notion of part standardization apply in synthetic biology? If so, how do you refine the definition? If not, what are the possible down sides to no longer defining part standards? I'm all for moving forward, but I'd like to know what I'm moving towards." Faculty Instructor

"About time. And good job!" Faculty Instructor

The Open Sequence Format

After many meetings and brainstorming sessions we decided to propose The Open Sequence Format via RFC95 that is intended to replace the current Biobrick standard RFC10 in order to reduce restrictions on parts submitted to the Parts Registry. Crucially, this RFC removes the sequence restrictions imposed by RFC10 regarding the removal of the restriction enzymes sites EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, and PstI from parts before they are eligible for inclusion in the Parts Registry.

You can download our most current draft of the RFC95 below:

File:9.27.13 RFC 95.pdf

Contact us with any suggestions or questions by shooting us an email at: mhammerling at gmail dot com

Quality Control and The Open Sequence Format

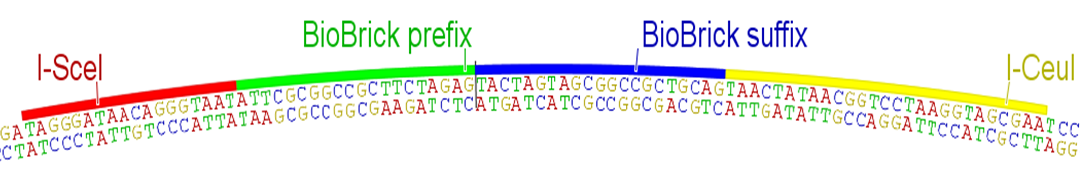

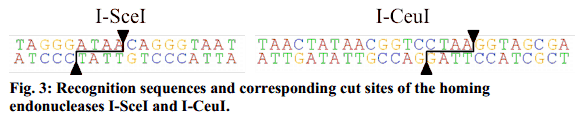

Quality control is critical for any serious engineering endeavor. While teams SHOULD sequence verify their parts to detect point mutations and small indels, the BioBricks Foundation needs a simple and rapid method for determining that parts are at least the correct size when submitted to The Registry. Currently this quality control is achieved through the use of the restriction sites present in the BioBrick prefix and suffix, resulting in highly restrictive rules for part submission. Therefore, we propose an alternative submission plasmid, pSB1C95, featuring the homing endonucleases I-SceI and I-CeuI and their corresponding restriction enzyme sites for quality control purposes. Parts MUST be submitted between the BioBrick prefix and the BioBrick suffix in pSB1C95, and the homing endonuclease sites I-SceI and I-CeuI MUST NOT be contained within the part itself, though the probability of this is negligible for gene-sized or even operon-sized parts (Fig. 4). There are no other rules or restrictions for part submission.

The Genbank file for our proposed submission standard may be found here:Media:PSB2C3.gb

Unlike typical 6 bp restriction sites, these homing endonuclease sites are 18 bp and

27 bp in length, with a tolerance of sequence degeneracy corresponding to a normal

restriction site 10 to 12 bp long. However, the probability of even a 10 bp sequence

randomly occurring in a submitted part is orders of magnitude lower than a 6 bp site,

thus effectively eliminating the problem of illegal sites for the purposes of rapid quality

control (Fig. 4).

Conclusion

Maintaining a genetic part repository is an inherently labor-intensive and error-prone process, but one that supplies a valuable service to both veteran and novice research groups. It is important to employ strategies that enable simple quality control workflows and maximize utility to the end user. We believe that the Open Sequence Format eliminates user problems associated with sequence restrictions while minimally impacting quality control workflows at the repository. Please see the RFC link above for full details.

"

"