Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Project/MFC

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

h3,h4{clear:both;} | h3,h4{clear:both;} | ||

#leftcol h4{color:#ff6600; padding-left:20px;} | #leftcol h4{color:#ff6600; padding-left:20px;} | ||

| - | #leftcol div.thumb.tleft{margin-left: | + | #leftcol div.thumb.tleft{margin-left:20px; margin-right:20px; clear:both;} |

#leftcol ul {clear:both;} | #leftcol ul {clear:both;} | ||

#leftcol ul ul{clear:both;} | #leftcol ul ul{clear:both;} | ||

Revision as of 17:17, 26 October 2013

Microbial Fuel Cell

Overview

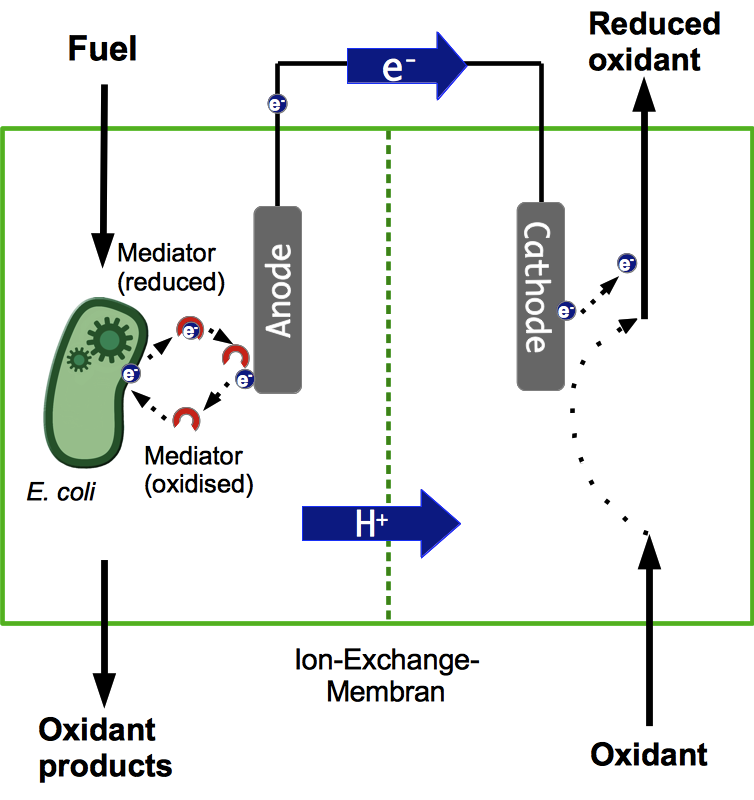

A microbial fuel cell (MFC) can be utilized for power generation through the conversion of organic and inorganic substrates by the use of microorganisms. The fuel cell generally consists of two separate units, the anode and cathode compartment which are separated by a proton exchange membrane (PEM). Microorganisms, acting as biocatalysts, release electrons during metabolic reactions and transfer them to the anode of the fuel cell. The protons being freed up during this process are transferred to the cathode compartment through the PEM. The electrons pass through an external load circuit to reduce an electron acceptor located in the cathode compartment and by doing so, create an electric current. The most significant factor in this system is the bacteria ability to transfer electrodes to the anode. There are lots of other aspects to consider though, all of which are vital for the successful operation of a fuel cell.

Most existing projects rely on using mixed cultures of different bacteria in the anode compartment. However, in most cases these systems aren’t characterized very well, often it is not even known which species are part of these cultures. This makes it almost impossible to improve the system by genetic engineering. Applying such a black box system outside of a laboratory might also pose safety risks. Another disadvantage is, that some of the species might be quite sensitive to different kinds of stress, like Geobacter sulfurreducens, which are very susceptible to oxidative stress.

For these reasons, Bielefelds 2013 iGEM Team decided to develop a system which only relies on E. coli for power generation. The main benefit being that these bacteria grow fast and are quite robust regarding cultivation conditions. Another advantage over a mixed culture is that the potential risks of using such a single-strain culture are much more easily assessed and can be reduced by systematic manipulation of the bacterial genome.

Theory

Cultivation conditions

In general microorganisms utilize three different methods to release electrons produced during the metabolic oxidation of high-energy organic or inorganic substrates. Because the reduction of oxygen, also called aerobic respiration is the most efficient possibility for many bacteria, including Escherichia coli, these metabolic pathways are preferred if oxygen is available. In a microbial fuel cell, however, an aerobic metabolism is undesired, since the electrons are directly transferred to oxygen and thereby cannot be used to produce current. Thus, anaerobic culture conditions are necessary.

Without oxygen bacteria can generate energy through different forms of fermentation and anaerobic respiration. During fermentation and anaerobic respiration, electrons are directly transferred to soluble electron acceptors. In case of Escherichia coli mixed acid fermentation under formation of metabolic end products like lactate, acetate and ethanol has to be avoided by the choice of suitable cultivation parameters.

Based on these considerations anaerobic respiration is left as the only suitable option for current generation in a fuel cell, when using the electrode as the terminal electron acceptor. For this reason, construction of the fuel cell, cultivation parameters and genetic modifications of Escherichia coli are aimed at enabling anaerobic respiration.

- Requirements:

- avoid aerobic respiration

- avoid fermentation

- accelerate anaerobic respiration

General design

The general design of a microbial fuel cell is mainly influenced by the shape of the electrode chambers. A very simple design is called the “H” shape, which usually consists of two bottles or other vessels, connected by a tube containing a suitable separation material. Further investigations underlined the general usability of this system to test materials or parameters, but the power gain seems rather low. This is most likely the case because of the slow proton exchange through the tubes and because of a high internal resistance (Oh et al., 2004; Oh and Logan, 2006).

There are many other possible shapes, like a cylindrical reactor with a concentric inner tube that acts as the cathode to enable a continuous flow. One specific design, proposed by H. P. Bennetto (Bennetto, 1990), is often used for research purposes. The system consists of plastic elements in form of two solid plates and two frames, as shown in figure 2. The frames are placed between the plates and form two reaction compartments, separated by a cation exchange membrane. Furthermore, every compartment is equipped with electrodes to enable a flow of electrons. To create a system with the option for anaerobic cultivation with simultaneous aeration and the possibility to add or remove liquid, the elements are fitted with ports. To ensure the system is air-tight, rubber gaskets are fitted between the plastic parts. The endplates are held together by four threaded rods.

- Requirements:

- formation of a closed system

- possibility for axenic cultivation

- possibility for anaerobic conditions

- large internal surface

Anode

In order to be used as an anode, a material has to be highly conductive, biocompatible and chemically stable under the conditions present inside the fuel cell. Many traditional materials like copper are not suitable, because of the highly toxic effect of heavy-metal ions to bacteria. Platinum works excellent, but is extremely expensive. Several carbon-based materials provide a cheap but practical alternative though. Regarding this, the surface area is a very important factor for high current production. Previous investigations showed that current increases with the overall internal surface in the following order: carbon felt > carbon foam > graphite (Chaudhuri and Lovley, 2003).

- Requirements:

- high conductivity

- good biocompatibility

- long-term physical and chemical stability

Cathode

Because of its low overpotential in combination with carbon electrodes and the resulting working potential, which is close to its open circuit potential, potassium ferricyanide (K3)[Fe(CN) 6]) is the most frequently used electron acceptor in microbial fuel cells in research scenarios (Logan ‘’et al.’’,2006). However, one has to consider that the reoxidation by oxygen is very low and the diffusion through the PEM is not negligible, so that the oxidation of this substance can affect the performance of the MFC when operated for long periods of time (Rabaey ‘’et al.’’ 2005). Alternatively oxygen can be used as a very effective electron acceptor in combination with an open-air electrode. For an effective oxygen reduction, however, high-cost platinum catalysts are necessary. For this reason, this option is rarely used (Sell ‘’et al.’’, 1989).

- Requirements:

- good reduction performance

- good reoxidation

- high long term stability

Compartment separation

Although almost all microbial fuel cells use proton exchange membranes as the separation element between anode and cathode compartment, it is possible to use more simple constructions like salt or agarose bridges. These basic separation systems, however, don´t reach the power output of membrane based systems because of the high internal resistance. Cation exchange membranes offer very defined properties and ensure a better current output because of their high selectivity for the passage of positive charged ions. However, in this context it has to be considered that the PEM could be permeable to chemicals and oxygen, which could influence the long term performance of the cell (Logan ‘’et al.’’,2006).

- Requirements:

- high selectivity for positive ions

- impermeability for chemicals and oxygen

Measurement system and protocol

The set up described here is intended to acquire matchable data regarding the power output gained with different bacteria strains while using mediators for the electron transfer.

When operating a microbial fuel cell, numerous different factors influence the power output that can be measured. Number and growth phase of the bacteria in the anode chamber are among the most important. The reaction taking place in the cathode is just as critical, since a bad setup can lead to the speed of the anode reaction significantly declining over time or not taking place at all. The properties of the proton exchange membrane and the electrodes are also quite important for the speed of the reaction.

Choosing an appropriate resistance is vital as well. If the resistance is too high, reduced mediator species accumulate at the anode and the voltage measured does not provide information about how fast the bacteria are able to reduce the mediator. Other factors come into play as well: The diffusion speed of the mediator, diffusion of cations through the membrane, agitation of the solution and the buildup of a biofilm at the anode have an influence at the power output of the fuel cell. When choosing a multimeter to measure the data, the internal resistance of the device has to be kept in mind.

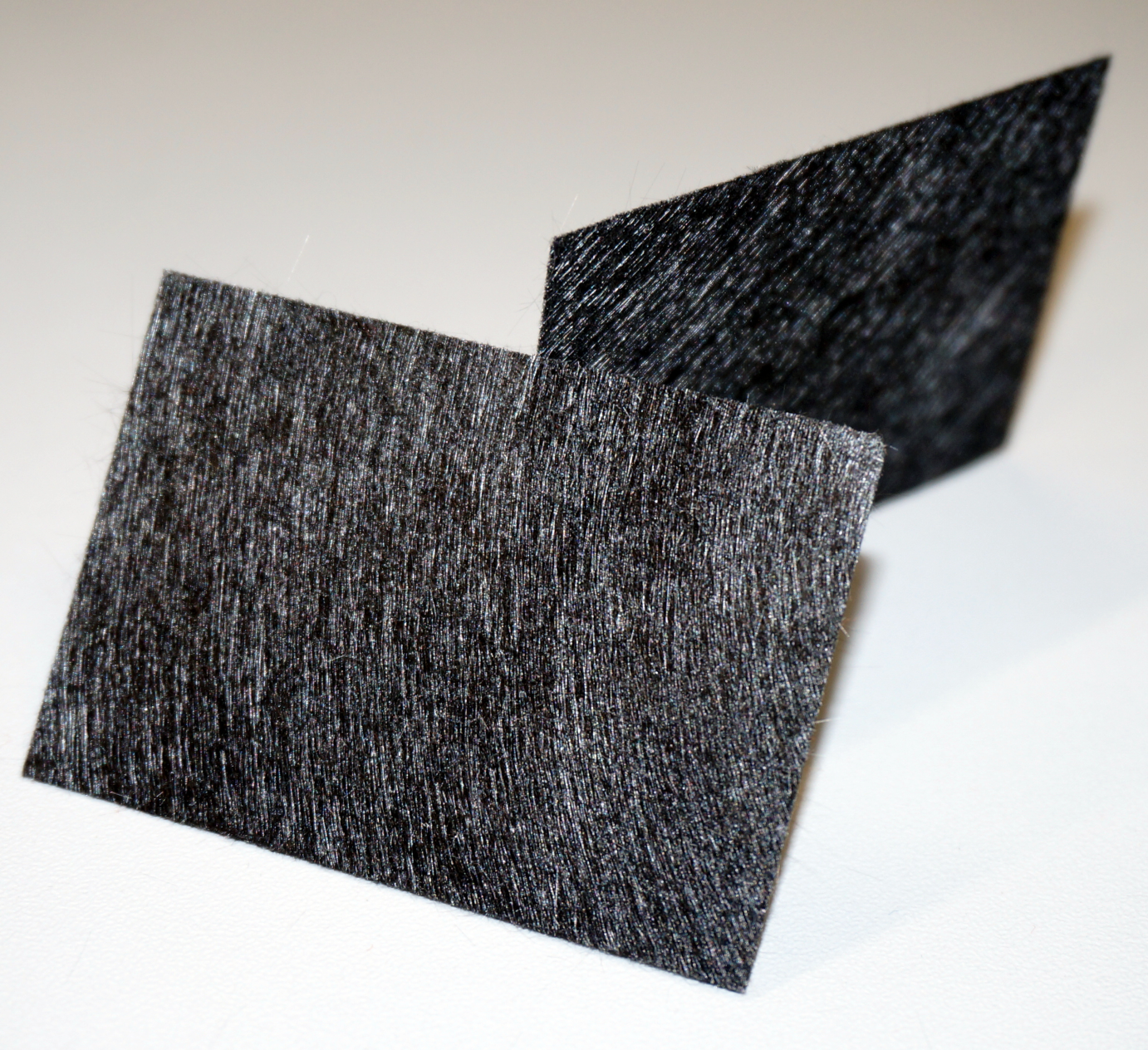

A standard measurement set up was established to generate data with fuel cell experiments. The experiment is carried out in a third generation fuel cell if not specified otherwise. A Nafion N117 proton exchange membrane manufactured by DuPont (for further information [http://www2.dupont.com/FuelCells/en_US/assets/downloads/dfc101.pdf see here]) is used to separate the anode and the cathode chamber. The surface area is 25 cm2 in each chamber. The electrodes are placed in the middle of each chambers, their dimensions are approximately 0.5 cm x 48.4 cm2. The exact surface area of the electrodes is unknown, since the carbon cloth is composed of extremely thin filaments and has a rough surface. However, it is assumed that the surface area is roughly the same for each electrode used, since the material is identical.

The cathode chamber was filled with 29 mL of a 20 mM solution of potassium ferricyanide in M9 medium. Bacteria were grown aerobically in shaker flasks on M9 minimal medium with 5.1 mg glycerol as a carbon source. In case the bacteria carry a plasmid with an inducible promoter, induction was carried out 2 hours after inoculation. The optical density of the culture was periodically measured until it reached 1. At this point, 26 mL of the medium containing the bacteria were injected into the anode chamber of the fuel cell.

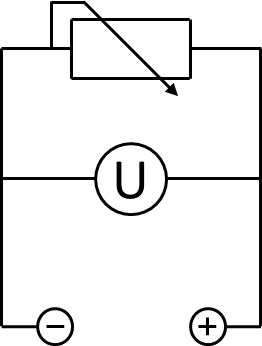

A 200 Ω resistor was wired between the anode and the cathode chamber. A UT 803 multimeter by UNI-T was used to measure the voltage across the resistor. The according electrical schematic is presented in figure 3. To generate polarization and power curves, the resistance was changed from 10 Ω to 10 kΩ in a cascade of 6 different values. The measured voltage for every resistance was registered after 10 minutes to enable the system to reach a constant value.

MFC-Evolution

To see how well the different BioBricks we create really work in the designated environment the design and construction of a suitable microbial fuel cell was necessary. This fuel cell has to meet several requirements. As explained previously it should consist of two chambers, separated by a material that is only traversable for cations. Both chambers have to contain an electrode, which has to be electrically conductive. Also, they should have a large surface area, in order to allow contact to a high number of electron donors at the same time. Both the anode and the cathode chamber also have to be air-tight, since the reaction has to take place under anaerobic conditions. For obvious reasons, we aim at keeping the costs for the cell low by using materials which cost as little as possible while still performing well.

Construction of a first prototype began in May. After initial testing, the design underwent significant changes over the course of the project. Important stages of this process are shown below, along with a description of their design and the flaws that led to the planning of a new model

The Film Canister Cell

This is a model designed to gain better understanding about the general concept of galvanic cells and microbial fuel cells. It was used with different chemicals, yeast and the E. coli KRX strain. It also allowed the collecting of experiences with the equipment used for measurement. The anode and cathode chambers are film canisters. Both have holes in their walls which are connected by roughly 2 cm long part of a 15 mL centrifugation tube. The individual parts are held together by hot-melt glue. The centrifugation tube is filled with 3 % agarose, which acts as a salt bridge to allow protons to pass from anode to cathode chamber. In both chambers, pieces of carbon tissue (see Figure 4) act as the electrode.

The biggest problem of this design is the salt bridge connecting both chambers. After being submerged in liquid for a while, it tends to become loose and glide out of the centrifugation tube. Furthermore, the construction does not allow for anaerobic operating of the fuel cell.

- Dimensions per Chamber:

- height: 50 mm

- diameter: 32 mm

- volume: 40.2 mL

The Film Canister Stack

The film canister stack consists of five film canister cells connected in series. This increases the voltage that can be obtained by connection the single cells in series. The individual canister cells are connected with copper wires. Because of the higher voltage generated it was possible to operate a single low power light-emitting diode, using a high concentrated baker's yeast suspension and methylene blue in the anode chamber.

- Dimensions per chamber

(10 total):- height: 50 mm

- diameter: 32 mm

- volume: 201 mL total

The Second Generation Fuel Cell

This cell was designed with anaerobic operation in mind. The plastic parts needed were ordered from the workshop of the faculty of biology at Bielefeld University. The overall design is inspired by the fuel cell proposed by Benetto (Bennetto, 1990). Two frames make up the anode and cathode chamber. They are enclosed with two flat plates, which each have four bores. Threaded rods are put through the bores. The construction is held together by these rods, which have tightly fastened nuts on their ends.

All plastic parts are separated by thin rubber gaskets. A nafion N117 membrane is jammed between the two frames to allow cations to travel between the chambers. The two electrodes were initially cut out of the same carbon tissue as the ones used in the film canister cells. The rims were sown together with extra durable yarn to prevent the material from frazzling. These electrodes were held in place by two plastic pars plugged in each chamber. The copper wire connecting the electrode runs through two holes on the top of each plastic frame.

Initial testing revealed that the carbon cloth electrodes didn’t seem to be as conductive as expected. For this reason they were replaced with electrodes made from another kind of carbon material, which were obtained from University of Readings [http://www.ncbe.reading.ac.uk/ National Centre for Biotechnology Education ]. However, the material is not very strong and easily ruptures, especially when wet. This made it difficult to connect the copper wires and to hold the electrodes in place within the chambers. The design also lacked a way to gas out the medium with nitrogen. This was important to establish anaerobic conditions within the fuel cell.

- Dimensions per chamber:

- height: 40mm

- width: 40mm

- depth: 14mm

- volume 22,4 mL

The Third Generation Fuel Cell

The fuel cell consists of six plastic parts. The overall design is similar to 2nd generation cell, but the frames are split up into two parts each. This allows for the carbon electrodes to be jammed between two frames, as was already the case for the membrane before. This ensures the fragile carbon cloth is fixed in the centre of each chamber and can be tapped by squeezing a wire between the gaskets. Since the material is extremely thin, bacteria and medium can diffuse through the electrode and travel between both halves of a single chamber.

The second important change from the previous design is the introduction of four tube connectors on each frame. This allows aeration of the anode chamber with nitrogen gas and further inventions in the system. The copper wire connecting the electrodes is replaced with platinum, because of the rapid copper-oxidation, resulting in a decreased conductivity.

- Dimensions per chamber:

- height: 50mm

- width: 50mm

- depth: 12mm

- volume: 30 mL

The iGEM-York Cell

Since the iGEM Team York_UK is also doing work related to microbial fuel cells this year, we offered to send them one of our fuel cells to conduct their experiments in. Our design didn’t fully meet their requirements, especially since it was too large. After consulting with two of their team members, we build a small fuel cell based on the 3rd generation design and sent it to York.

- Dimensions per chamber:

- height: 25mm

- width: 25mm

- depth: 12 mm

- volume: 7,5 mL

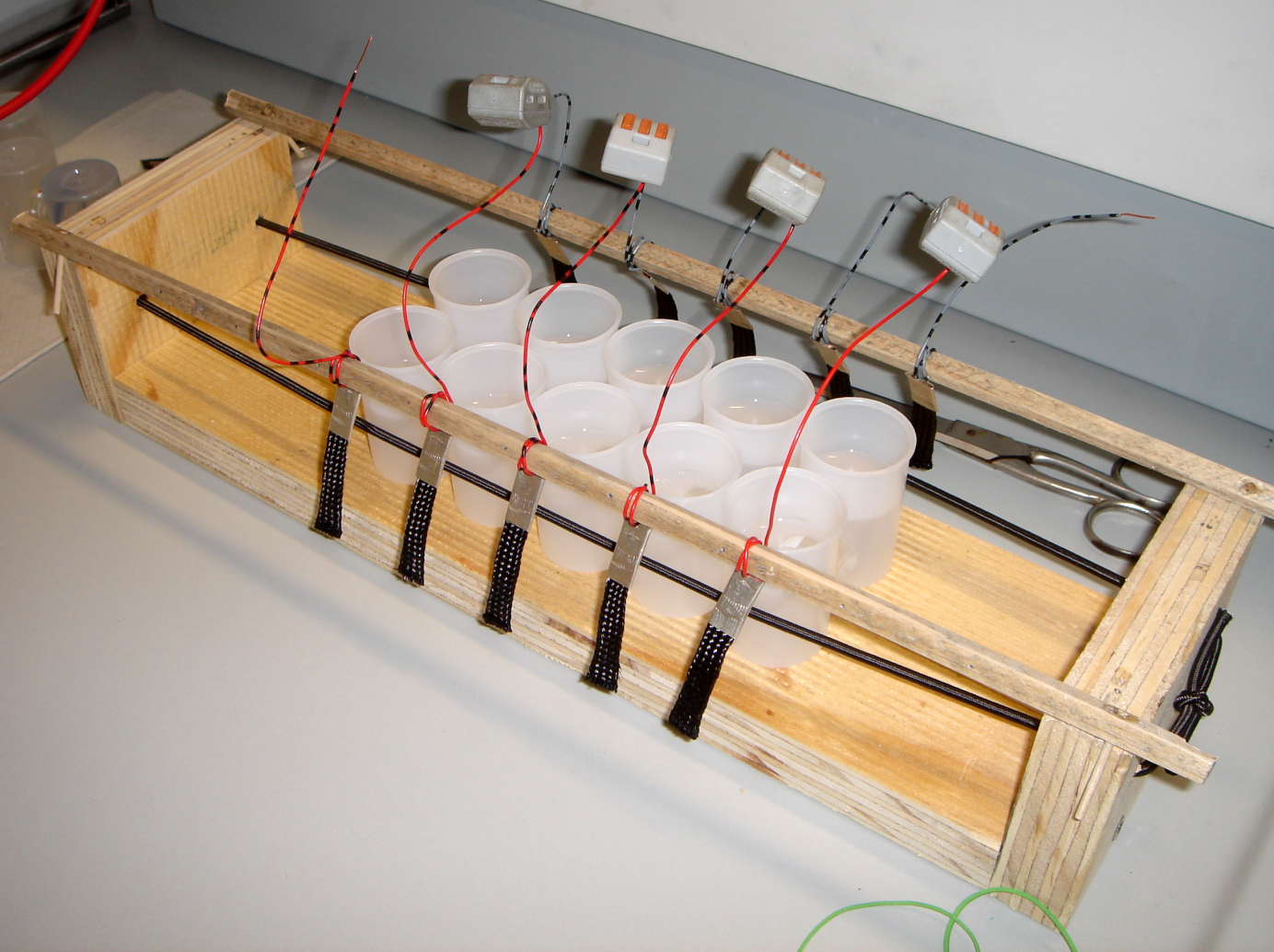

The Stack

In order to increase the power output of the fuel cell, a fuel cell stack was built based on the third generation design. It consists of alternating anode and cathode chambers, five of each, jammed between two cover plates. Using copper wiring, the five chamber-pairs are connected in series. Physically, they are separated by 1 mm thick stainless steel tiles, which act as bipolar plates.

- Dimensions per chamber

(10 total):- height: 50mm

- width: 50mm

- depth: 12mm

- volume: 150mL total

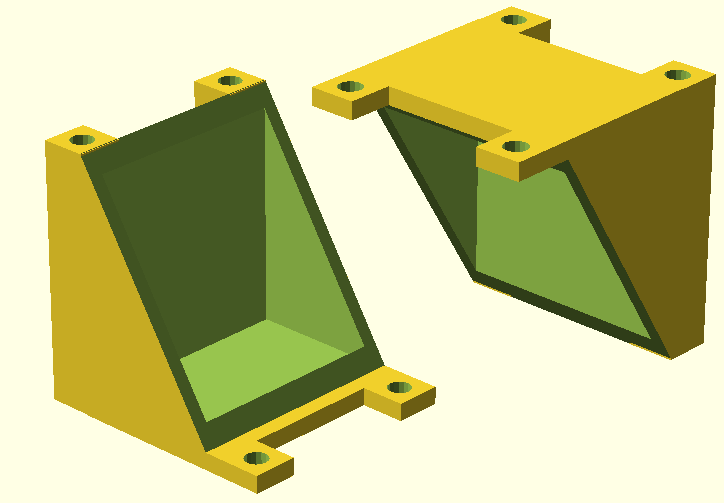

3D printing

To make the microbial fuel cell accessible to everyone, an additional model was developed which can be produced using a 3D-Printer. 3D-Printers are becoming more and more common and if none is available, the model can be ordered online from a 3D-printing shop.

For our 3D-printed microbial fuel cell it was important to apply material that does not inhibit microbial growth. To make sure this is the case, E. coli KRX was cultivated in the presence of two different kinds of plastic commonly used for 3D printing. These materials were Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and Polylactic acid (PLA), which are both thermoplastics that become moldable when heated and return to solid once the temperature drops.

A proper material for gaskets is essential as well, so different kinds of polysiloxane were tested in the same way. The rubber gaskets used in second and third generation MFC designs were also probed.

- Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene

- ABS as a polymer can take many forms and can be engineered to have many properties. In general, it is a strong plastic with mild flexibility (compared to PLA).

- It's strength, flexibility, machinability, and higher temperature resistance make it often a preferred plastic by engineers and those with mechanical uses in mind.

- ABS can be smelt down and recycled very easily provided it is available in suitable purity. Sorting methods do exist to separate ABS from mixed wastes with high efficiency.

- Polylactic acid

- Created from processing any number of plant products including corn, potatoes or sugar-beets, PLA is considered a more 'environmental friendly' plastic compared to petroleum based ABS.

- When properly cooled, PLA seems to have higher maximum printing speeds, lower layer heights, and sharper printed corners.

- PLA is biodegradable, having a typical lifetime of about 6 months to 2 years until microorganisms break it down into water and carbon dioxide.

To assess the issue of possible growth retardation, we cultivated E. coli with each material and compared the measured growth curves to a control cultivation without added plastics.

The results shown in in figure LILA PAVIAN and figure UMBRA SEEPFERDCHEN demonstrate, that both ABS and PLA are biocompatible. Also, all brands of polysiloxane except B1 and the rubber are suitable as gasket material.

Models

3D-Models were programmed with the software [http://www.openscad.org/ openSCAD], exported as .stl-files and translated into G-Code using [http://slic3r.org/ Slic3r].

Initially, slicing and printing took place at the local [http://hackerspace-bielefeld.de/ hackerspace] with counseling by the groups experienced members. The printer, a [http://printrbot.com/ Printrbot Plus v2] was made available by the hackerspace community as well. After a total of roughly 34 hours of work, a first model was successfully printed from ABS. Like the models described in the MFC-Evolution paragraph, the design was changed several times. Some of the results can be seen in Figure 17. In early August, Bielefeld Universitys faculty of physics offered their help. They printed out all subsequent designs with their [http://www.reprappro.com/products/mono-mendel/ RepRapPro Mono-Mendel] using PLA plastic and also executed the slicing process.

The final model, illustrated in figure 19, was finished in September. It features a 4-part-design like the second generation model described in the MFC-Evolution section and has tube connectors for aeration of each individual chamber. Polysiloxane is used instead of rubber gaskets, the membrane and electrodes are jammed between the four frames of the reaction chambers. The end plates are held together by M3 threaded rods with M3 nuts. The materials necessary for building this fuel cells chassis cost less than 4€ an the cell is biodegradable. The .stl-file is available for download here.

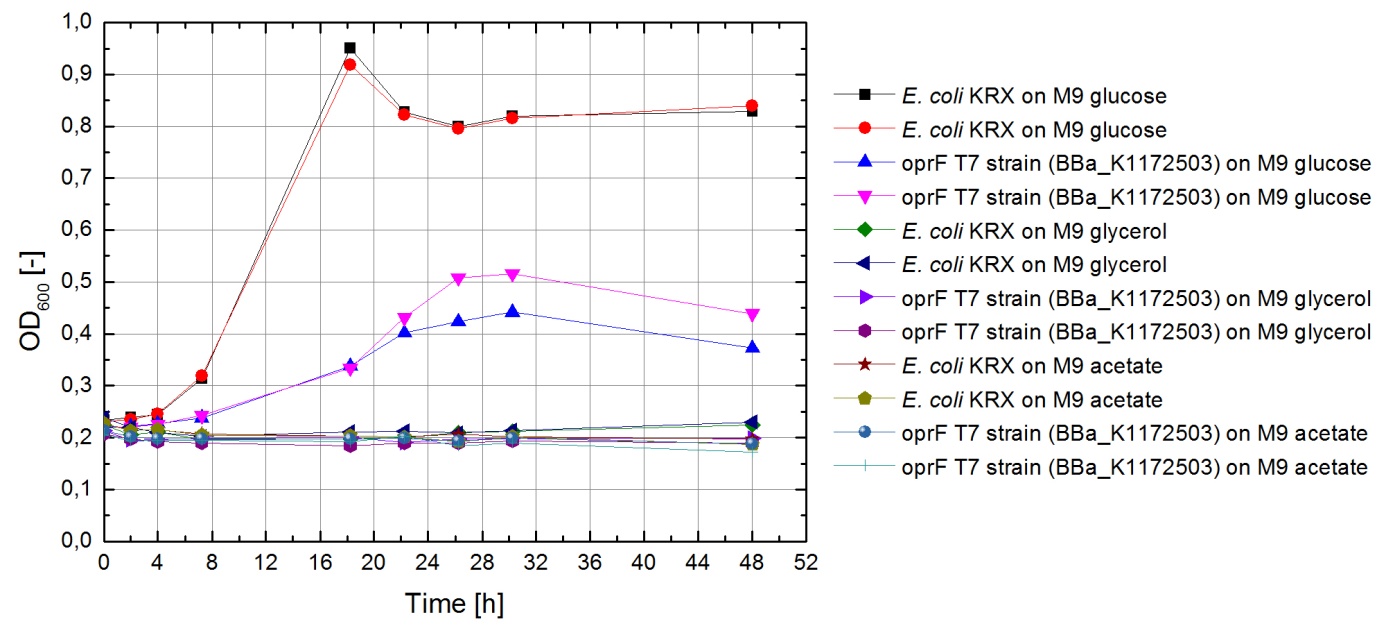

Media and carbon sources

As explained previously, E. coli have to respire under aerobic conditions in order for the microbial fuel cell to work. This can prove to be problematic when using media such as LB, because in the absence of oxygen the bacteria might use the available carbon source for fermentation. To prevent this, the different strains which were tested in the fuel cell were cultivated in M9 minimal medium. After consulting Dr. Falk Harnisch concerning the fermentation problem, we decided to supplement the M9 medium with different carbon sources to test how this affects bacterial growth under anaerobic conditions. The goal of this experiment was to find a carbon source which is well suited for aerobic respiration, but can’t be used for fermentation by the bacteria.

Tests were carried out with glucose, glycerol and acetate. The amount of substrate supplemented into the medium was adjusted, so that the amount of carbon atoms was the same for each culture. The concentrations were 5.0 g/L for glucose, 5.1 g/L for glycerol and 6.8 g/L for acetate. In all cultivation experiments, two biological replica of every strain and substrate combination were prepared and each sample was diluted and measured twice. Anaerobic cultivations were conducted in 30 mL test tubes with rubber lids. Samples were taken by piercing the lid with a syringe. For aerobic cultivations shaker flasks were used. The strains tested were the KRX wild type and the KRX OprF T7 ([http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1172502 BBa_K1172502]) strain. The latter overexpresses large porin-proteins when induced with rhamnose. Induction was carried out with 4,2 mL/L of a 240 g/L rhamnose solution 1 hour after inoculation. All cultures were inoculated with an optical density of 0.22. Temperature was kept at 37°C during cultivation.

Figure 20 shows that under anaerobic conditions both strains grow well on glucose but seem to be unable to use acetate or glycerol efficiently.

To ascertain whether glucose, glycerol or acetate are suitable substrates under aerobic conditions, eight additional cultures were inoculated with both strains. For these cultures only an end-point determination was carried out. The results can be seen in figure 21. They indicate that acetate is, as expected, not a suitable substrate. Growth is best with glucose as a substrate, but glycerol yields satisfactory results as well.

The data acquired points to glycerol being the most suitable substrate, since the bacteria seem to have difficulties using it for fermentation but show satisfactory growth under conditions allowing for aerobic respiration. To make sure glycerol can also be used for respiration with terminal electron acceptors other than oxygen, bacteria were cultivated under anaerobic conditions in M9 medium containing glycerol as a carbon source and potassium nitrate as a soluble electron acceptor.

The results of this experiment are shown in figure 23. Cultures which were supplemented with KNO3 grow significantly faster than those that weren’t, indicating that potassium nitrate is indeed used as a terminal electron acceptor for anaerobic respiration.

Based on these results, M9 medium with 5.1 g of glycerol per liter is used for all future experiments with the fuel cell.

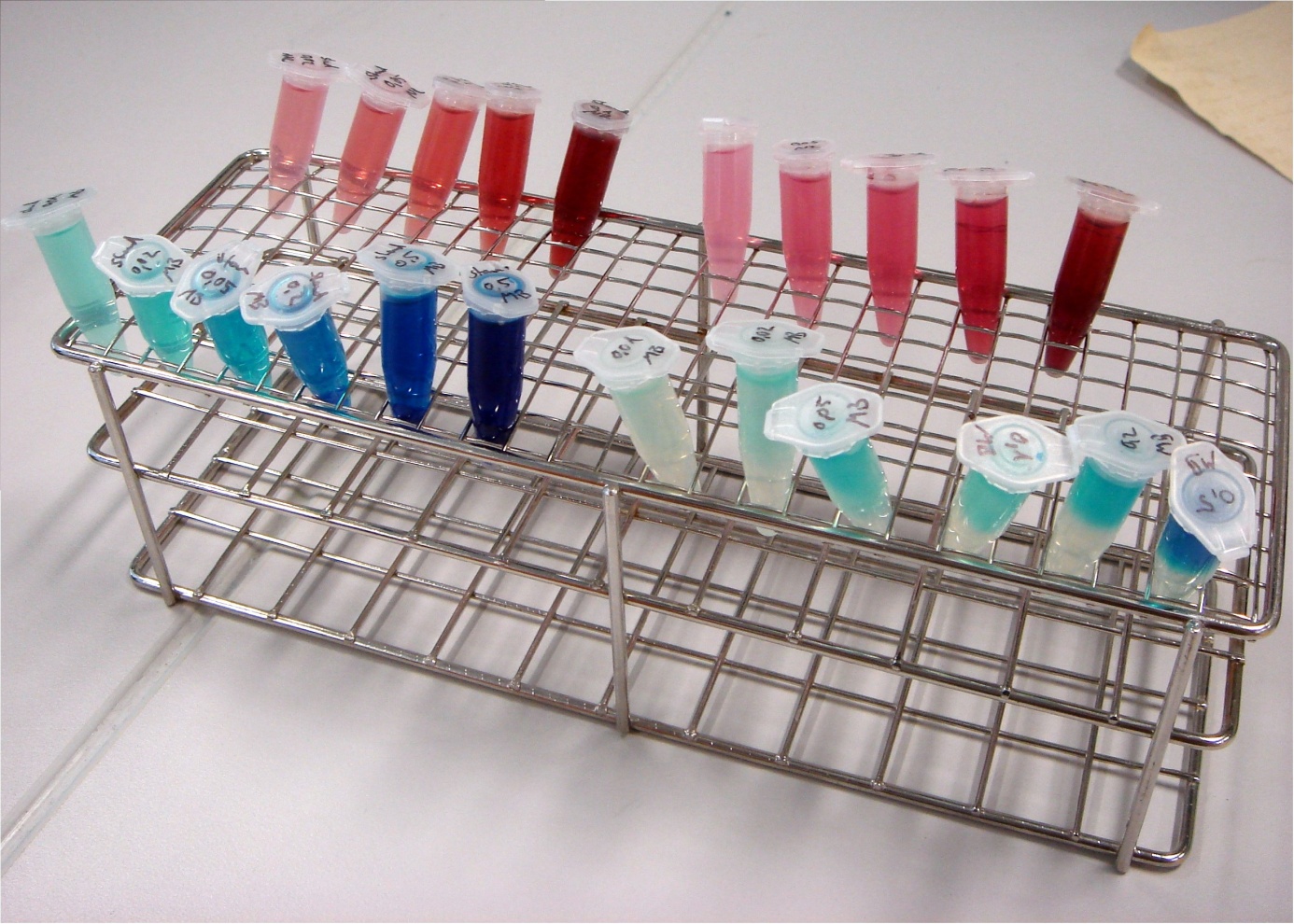

Exogenous Mediators

Look here for general information about redox mediator molecules.

Redox molecules which are chemically synthesized can be added into the anode chamber of the fuel cell to act as mediators, transporting electrons from the bacteria to the fuel cells anode. Here, these chemicals are referred to as exogenous mediators.

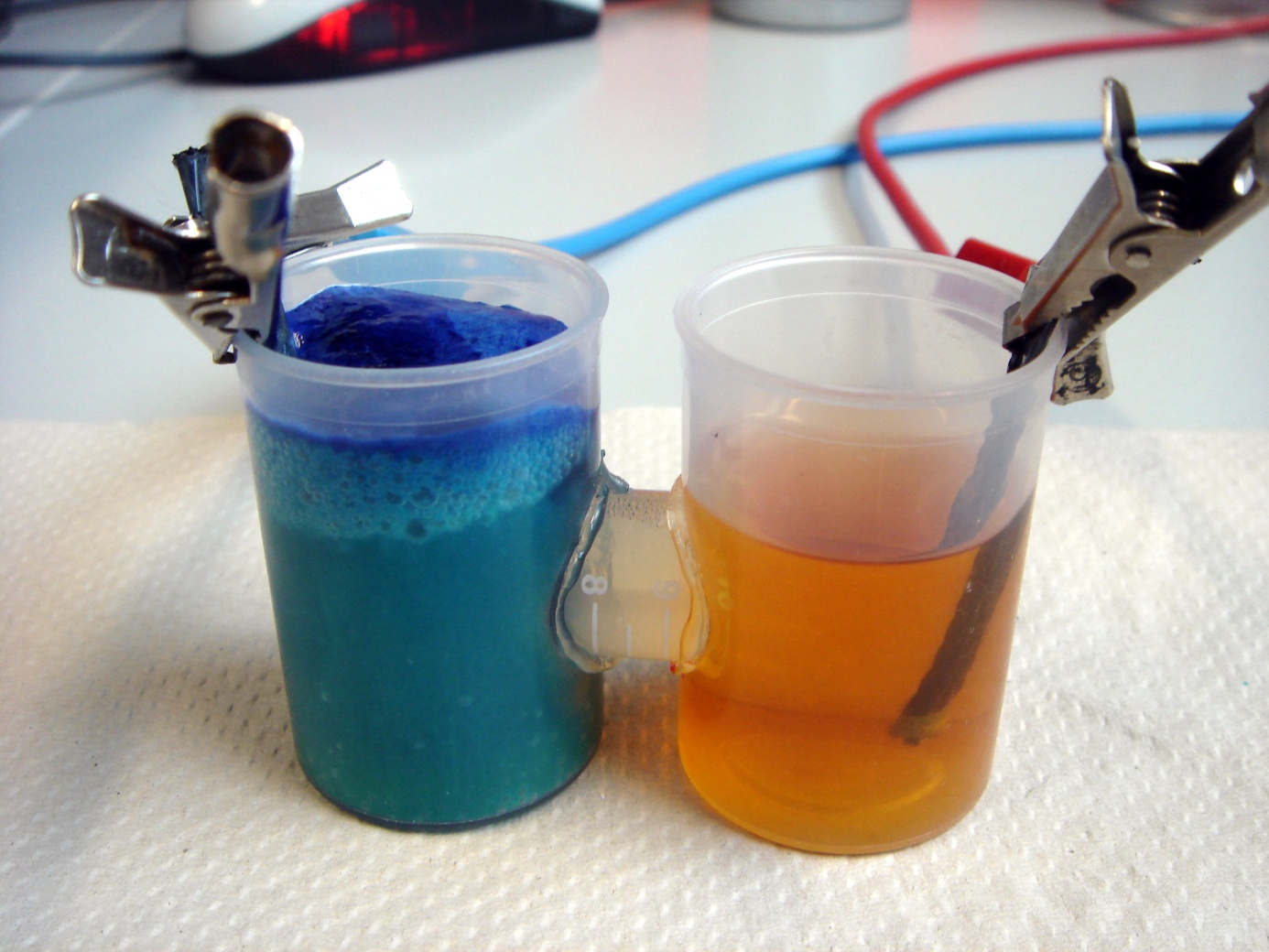

To identify a exogenous mediators which can easily be reduced by E. coli, a simple experiment was conducted. A culture of E. coli KRX was distributed into 1.5 mL reaction tubes. Methylene blue and neutral red were added in varying concentrations. Since all mediators tested lose their color when reduced, a change in the color of the solution indicates that the bacteria are able to reduce the respective compound. Incubation took place at 24°C for 24 hours.

In figure 24 it can be seen that the samples containing methylene blue show a reduction of color intensity after incubation. Oxygen is able to reoxidize leucomethylene blue to the molecules blue form, so a blue color near the liquids surface is to be expected. Based on these results, methylene blue was chosen as the preferred exogenous mediator for further experiments.

When methylene blue salts are dissolved in water, they dissociate into anions and methylene blue cations (see figure 25). The conjugated electron systems of the molecule causes methylene blue solutions to appear in a dark blue color.

The compound can be reduced, accepting an electron and a proton in the process (see figure 25). This breaks up the conjugated electron system, which is why leucomethylene blue is colorless. The [http://employees.csbsju.edu/hjakubowski/classes/ch331/oxphos/standredpotentialtab.htm standard potential] of the methylene blue/ leucomethylene blue reaction is +0.01 V.

Results

Viable possibilities for the analysis and characterization of microbial fuel cells are polarization and power curves. By using different microorganisms, while keeping all other conditions the same, this measurement method allows for a direct comparison of the electrical power provided.

To record a polarization curve for the whole cell the electrical circuit described in figure 3 is used with a variable resistor box. Beginning with the lowest resistor, a periodic increase of the used resistance from 10 Ω to 10 kΩ is performed. As presented in figure A, the system reacts expectedly with an increase of the applied voltage and, after a few minutes, reaches a constant value, which is used for further investigations. When looking at the recorded voltage values in figure 26 it is obvious, that a mediator, in this case methylene blue, is essential for electron transport.

The polarization curve presented in figure 27 underlines this fact. To calculate the appropriate current values Ohm's law was used. The application of the reached voltage as a function of the current lead to a typical course in form of a characteristic correlation between voltage and current dependent on the used resistance.

By calculating the appropriate electrical power values and plotting a power curve as a function of the current (figure 28), the differences become even more significant. While the cultivation of E. coli and the experiment where only M9 Medium was used showed no significant differences, the cultivation containing 345 µmol/L methylene blue achieved a significantly higher wattage, but could not reach the level of the experiment where bacteria and mediators were used in combination.

All in all the calculation of polarization and power curves by changing the external load of the system via different resistors showed the huge importance of a suitable electron transfer system. The intended comparison of the different fuel cell generations was not possible, because the measurement-parameters were optimized during the course of the project and cannot be compared.

Besides the calculation of power curves the temporal process of power output is a very important parameter evaluating the overall performance of a microbial fuel cell, too. Figure D illustrates the electrical power as a function of time for the wild type E. coli KRX and a genetically modified strain of E. coli KRX containing the BioBrick BBa_k1172502 with the oprF gene under control of the T7 promoter.

Because of the identical cultivation conditions, using 2 identical MFCs with equivalent cell numbers in a temperature stabilized cultivation chamber and synchronized aeration with nitrogen , the visible difference between strains has to be a result of the biobrick inserted in the oprF srtain. The expression of the OprF-protein leads to a higher power output of nearly 500 µA for a 200 Ω resistance, while the KRX strain reaches only 150 µA.

Besides these scientific results the usage of the developed microbial fuel cell for various applications is possible. Because many of these applications need higher voltages than one cell can deliver, a stack of several cells is necessary. One easy way to realize a compact multi-cell system is a stack of several cells. The construction, described in the MFC-evolution part, contains 5 membranes, 10 electrodes, 20 frames and 40 gaskets and supplies a voltage of up to 2.4 Volts. Using the GldA-expressing strain it can be used for permanent operation of LEDs or little buzzers, or to power a small ventilator like shown in the video below.

References

- Bennetto, H. P. (1990). Electricity generation by microorganisms. [http://www.ncbe.reading.ac.uk/NCBE/MATERIALS/METABOLISM/PDF/bennetto.pdf Biotechnology Education, 1](4), 163-168.

- Chaudhuri, S. K., & Lovley, D. R. (2003). Electricity generation by direct oxidation of glucose in mediatorless microbial fuel cells. [http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v21/n10/abs/nbt867.html Nature biotechnology, 21](10), 1229-1232.

- Logan, B. E., Hamelers, B., Rozendal, R., Schröder, U., Keller, J., Freguia, S., ... & Rabaey, K. (2006). Microbial fuel cells: methodology and technology. [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es0605016 Environmental science & technology, 40](17), 5181-5192.

- Oh, S., Min, B., & Logan, B. E. (2004). Cathode performance as a factor in electricity generation in microbial fuel cells. [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es049422p Environmental science & technology, 38](18), 4900-4904.

- Rabaey, K., Clauwaert, P., Aelterman, P., & Verstraete, W. (2005). Tubular microbial fuel cells for efficient electricity generation. [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es050986i Environmental science & technology, 39](20), 8077-8082.

- Sell, D., Krämer, P., & Kreysa, G. (1989). Use of an oxygen gas diffusion cathode and a three-dimensional packed bed anode in a bioelectrochemical fuel cell. [http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00262465 Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 31](2), 211-213.

"

"