Team:Virginia/Applications

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 279: | Line 279: | ||

<div class="body"> | <div class="body"> | ||

<div id="groupbio"> | <div id="groupbio"> | ||

| - | <span> | + | <span>Chassis Improvements - BioSafety</span> |

<p><b>Polysialic Acid</b></p> | <p><b>Polysialic Acid</b></p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d7/Polysialicacidvgem.png" width="800"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d7/Polysialicacidvgem.png" width="800"> | ||

Revision as of 19:18, 26 October 2013

Polysialic Acid

The K1 strain of E. coli produces and encapsulates itself in alpha-2,8-linked polysialic acid (PSA), a polysaccharide that biochemically mimics the human glycoprotein Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM). This similarity renders virulent K1 E. coli poorly immunogenic in humans because they aren’t seen as foreign and are therefore cloaked from antibody opsonization and complement-mediated killing. Clearly, equipping our minicells with such protection would be highly advantageous for improving their successful delivery rate and reducing harmful immune responses.

A significant amount of machinery (14 genes in total) is required to generate the PSA capsule in K1 E. coli and transferring this ability over to the comparatively docile K12 E. coli is quite the feat. Thankfully, we were able to find previous work by Dr. Eric Vimr that accomplished just that and obtained a single pSR23 plasmid that contains all the required genes. We are currently in the process of confirming the presence of PSA on our K12 E. coli via antibody-labeled fluorescence microscopy.

Sources:

Ail

Ironically, in order to make our minicells as non-toxic and safe as possible we had to look toward the likes of the bacteria that caused the Black Plague. While it may seem strange, bacteria that have such success when infecting the human body have developed the best ways to avoid the traps of the immune system. For our innocuous minicells, the only source of harm to the body would come from an overreaction of its own immune system. Therefore, equipping our minicells with the immunoevasive tools of virulent bacteria actually makes them less harmful.

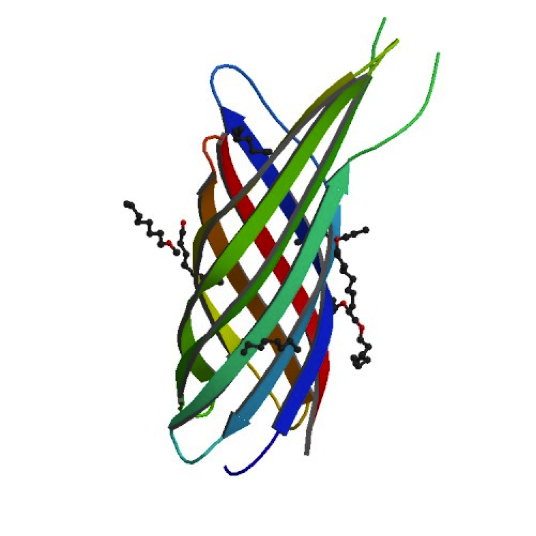

Our research led us to the Ail protein from Yersinia enterocolitica. Ail is just one of three invasion proteins cloned from Yersinia species, invasin probably being the most widely known. When present on E. coli, Ail confers a phenotype of attachment and invasion, though invasion is primarily limited to epithelial tissue. These qualities already make Ail an attractive protein for enhancing minicells role as a delivery vehicle, but they are not the primary reasons we chose to use it. Ail was also found to have both structural and functional homology with outer membrane proteins like Rck of Salmonella typhimurium, which grants high-level serum resistance. The serum resistance Ail grants to E. coli helps prevent the activation of the complement cascade—a primary defense mechanism of the immune system. The binding of complement proteins to bacteria usually spells their end: it triggers inflammation, draws phagocytic cells, facilitates phagocytosis, induces cell lysis, and coordinates opsonization by antibodies. By protecting our minicells from destruction, we can improve the chances of successful payload delivery and simultaneously reduce the risk of septic shock.

Sources:

IpxM Strain

With our FtsZ biobrick, minicells can be created in virtually any strain of E. coli. This allows us to choose strains that are best suited for a minicell’s purpose: safe delivery of contents. The use of traditionali E. coli strains is naturally limited in that regard, due to the toxic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) component of their outer membranes. LPS is a crucial part of Gram-negative bacteria’s structural integrity and also plays a protective role against certain chemicals and immune effectors. However, it is extremely endotoxic, evoking a strong immune response in human that can result in septic shock. It was found that hexa-acylated LPS is the trigger in humans, recognized by the human toll-like receptor 4 (hTLR4) and myeloid differentiation factor-2 (MD-2) complex. This complex activates the NF-kappaB transcription factor, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and eventually septic shock.

Thankfully, strains of E. coli have already been made to deal with this toxicity without significantly compromising the structural integrity of the bacteria. One such strain includes a mutation in the lpxM gene, which codes for a late-stage myristoyl transferase essential for the addition of secondary acyl chains on the Lipid A portion of LPS. This prevents the toxic hexa-acylation of LPS and exhibited a 10-fold reduction of toxicity in a murine model. We were able to obtain the lpxM mutant strain from the Yale E. coli stock center for use in our experiments. Recently, it was brought to our attention that a new strain, dubbed “Clear Coli”, utilizes six additional genetic mutations to further lower the risks of immunogenicity. While the strain is relatively new, the results are very promising with >95% reductions in endotoxin response in a Limulus amebocyte lysate test. In the future, we hope to use “Clear Coli” as our standard for minicell production.

Sources:

Targeting

Previous researchers who have worked on minicells have attached Protein A/G Fc receptors to an OmpA autotransporter located on the surface of minicells. This patented approach allowed them to add antibodies specific to their target host cell to purified minicells, thereby creating targeted minicells. Additionally, the antibody coating serves to protect the minicells from the host immune system and induce endocytosis when binding to certain target cell receptors. Such a modular targeting system is ideal for such a versatile vector. We hope to create a similar system that allows our minicells utilize the vast library of commercial antibodies available as highly specific receptors for a variety of applications.

Sources:

"

"