Team:British Columbia/Project/Caffeine

From 2013.igem.org

AnnaMüller (Talk | contribs) |

AnnaMüller (Talk | contribs) (→Characterization) |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/0/01/UBCCaf2.png" width="600"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/0/01/UBCCaf2.png" width="600"> | ||

| - | + | </center> | |

<br> | <br> | ||

<br/><b>Figure 1.</b> 12% SDS-PAGE gel with protein samples from extracted from <i>E. cloni</i>® 10G cells containing each of the caffeine constructs (under pBAD) induced with 2% arabinose for 3 hours at 37°C. No additional bands are visible in the expected range when compared to the uninduced control. | <br/><b>Figure 1.</b> 12% SDS-PAGE gel with protein samples from extracted from <i>E. cloni</i>® 10G cells containing each of the caffeine constructs (under pBAD) induced with 2% arabinose for 3 hours at 37°C. No additional bands are visible in the expected range when compared to the uninduced control. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | < | + | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Revision as of 00:32, 29 October 2013

iGEM Home

Contents |

Caffeine

Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine) is a powerful stimulant consumed in large quantities worldwide. Originally found in just coffee and tea beverage, caffeine has found its way into many different consumer products, like energy drinks (1). Following the trend of increased consumption, more and more research into the health effects of caffeine and more economical methods of production is being performed.

Currently, the most common method for the isolation of caffeine is the decaffeination of commercially harvested plants, such as green tea leaves and Coffea arabica beans. The ecological and financial burden of current caffeine production methods makes an alternative approach, such as microbial synthesis achieved through synthetic biology, much more desirable. While significant gains have been made with the microbial degradation of caffeine, its synthesis in a biological chassis is far less successful (4,5).

Rationale

The great demand for caffeine in food products and beverages makes this compound an exciting one to target for synthesis and incorporation in our ultrabiotic. The caffeine biosynthetic pathway serves as part of a proof-of-concept showing that the CRISPR system could be used to alter population dynamics in bioreactors through immunity to phage. By providing CRISPR immunity to a common phage and not to a certain rare phage, the system would allow the removal of caffeine-producing bacteria in a bioreactor through the addition of that rare phage. This has the potential to create a caffeinated or "decaffeinated" product. The mechanism of tunable populations is demonstrated in the “population control” section of our Wiki.

Objective

Our goal was to implement the caffeine biosynthetic pathway in E. coli to enable the production of caffeine in a bioreactor. This work would largely build on the previous efforts of the 2012 TU Munich team, which successfully obtained caffeine precursors when expressing caffeine’s biosynthetic machinery in yeast.

Chemistry

Caffeine biosynthesis occurs by successive modifications to purine nucleotide precursors such as AMP and GMP. Starting with xanthosine as substrate, the pathway below depicts the final stage of caffeine synthesis in organisms such as Coffee arabica. Xanthosine methyltransferase (XMT) starts by methylating xanthosine with the ubiquitous methyl donor S-adenosyl-L-Met (SAM), which acts as methyl donor for all subsequent methylations in the pathway. XMT also catalyzes the second step of the pathway, the removal of the ribose group.

Characterization

We obtained the three genes required for caffeine biosynthesis from the 2012 TU Munich. This included CaXMT, CaMXMT, and CaDXMT, which had previously been based on the natural plant genes and codon-optimized for expression in yeast. While not codon-optimized for expression in bacteria, believed that we could express them first in a rare codon-supplemented bacteria such as Rosetta Cells™. That way we could determine if it was possible for these three enzymes to be well expressed and obtained in an active form in bacteria before proceeding to the more costly step of codon-optimizing them for bacterial expression.

We proceeded by removing the yeast ribosome-binding site (rbs) and replacing it with a bacterial Shine-Dalgarno sequence. Each gene was cloned separately under an arabinose-inducible promoter (pBAD) and a constitutive promoter (pTET), in addition to a construct with all three under the same promoter. Expression was tested in a variety of conditions in E. cloni® 10G cells, but no expression was detected (Figure 1). This was expected as the genes are not optimized for normal bacterial expression. Unfortunately, Rosetta Cells™ already contain a chloramphenicol plasmid, pRARE, and as such, these caffeine constructs could not yet be transformed into the Rosetta Cells for further expression testing. Efforts are now under way for a kanamycin resistance marker to be cloned into each caffeine enzyme construct to allow for compatibility with the Rosetta Cells™.

Figure 1. 12% SDS-PAGE gel with protein samples from extracted from E. cloni® 10G cells containing each of the caffeine constructs (under pBAD) induced with 2% arabinose for 3 hours at 37°C. No additional bands are visible in the expected range when compared to the uninduced control.

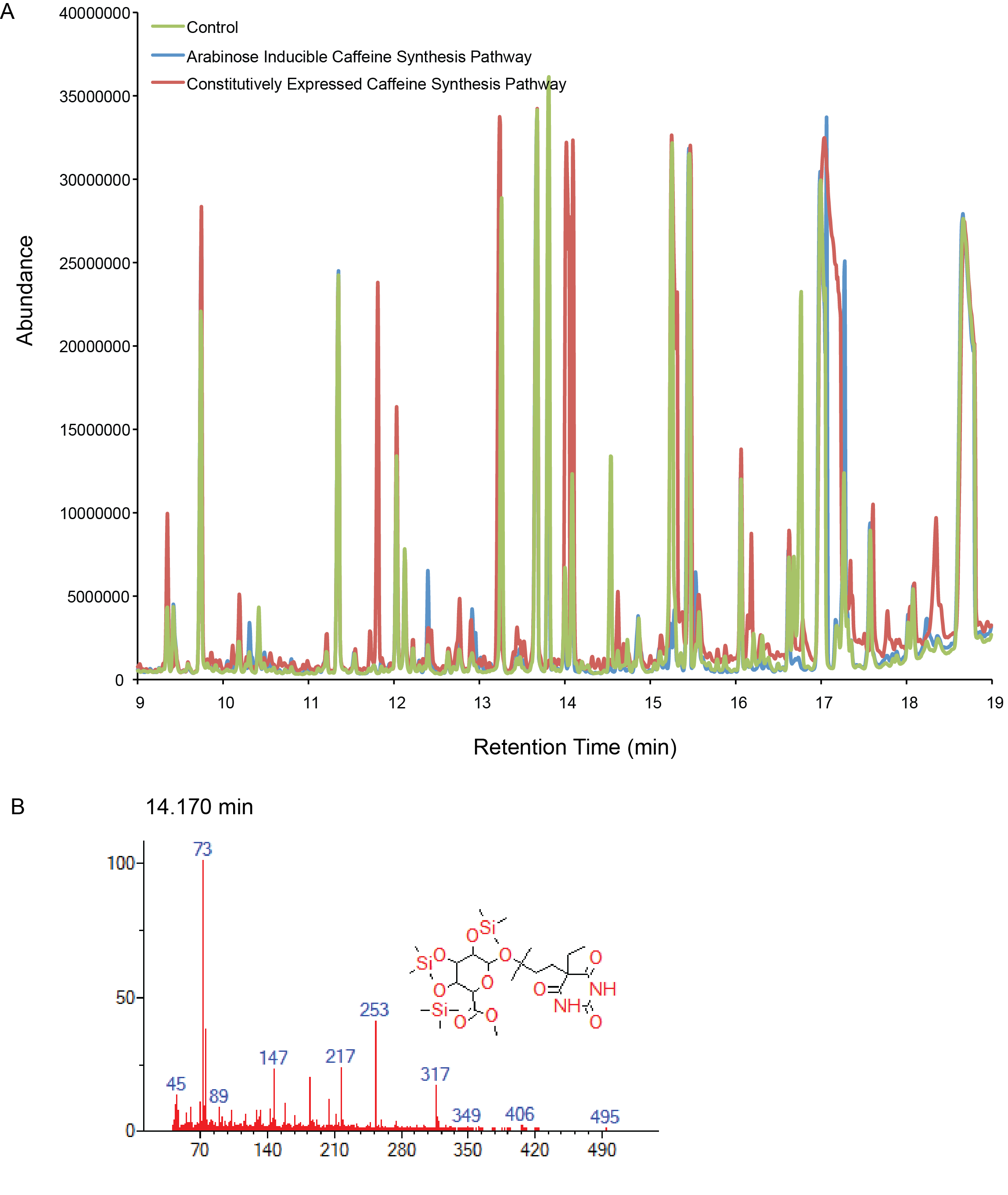

Figure 3. Compound generation identification by GC-MS. Chromatograms and mass spectra for select peaks are shown. Controls represent plasmids missing the gene of interest. A) Both the inducibly and constitutively expressed caffeine synthesis pathways. B) A compound matched to a library with low that could be related to the caffeine intermediates (xanthine derivates).

References

1) James, J.E. Caffeine. Addiction Medicine. 551-583 (2011).2) Uefuji, H., Ogita, S., Yamaguchi, Y., Koizumi, N., & Sano, H. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of three distinct N-methyltransferases involved in the caffeine biosynthetic pathway in coffee plants. Plant Physiol. 132, 372-380 (2003).

3) Vuong, Q.V., Roach, P.D. Caffeine in green tea: its removal and isolation. Separation & Purification Reviews. 43 (2013).

4) Lakshmi, V., & Das, N. Biodegradation of caffeine by Trichosporon asahii isolated from caffeine contaminated soil. Int. J. Eng. Sci. & Tech. 3, 7988 (2011).

5) Asano, Y., Komeda, T., & Yamada, H. Microbial production of theobromine from caffeine. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 57, 1286-1289 (1993).

"

"