Team:Greensboro-Austin/Smell degradation

From 2013.igem.org

Contents |

Introduction

p-Cresol (4-methyl phenol) is a volatile organic compound present in most mammal fæces, correlated with having an odor characteristic to humans as fæcal and detectable at dilute concentrations [10]. The compound is present in its highest concentrations in pig manure and is formed in this context by the anaerobic degradation of the amino acid L-tyrosine, which occurs in the metabolism of the natural intestinal flora (Antoine, Taillieu, & Thonart, 1997; Mathus & Miller, 1995).<ref>LibreOffice For Starters, First Edition, Flexible Minds, Manchester, 2002, p. 18</ref>

Pseudomonas putida

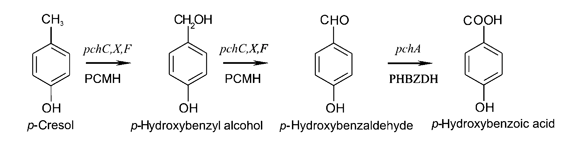

The pch gene cluster follows the protocatcechuate branch of the ortho pathway of p-cresol degradation, encoding for the enzymes p-cresol methylhydroxylase and p-hydroxybenzaldehyde dehydrogenase, which degrade p-cresol to p-hydroxybenzoic acid (Jõesaar et al., 2010). This pch cluster has been studied in multiple strains of Pseudomonas putida and other microorganisms. One of these P. putida strains, NCIMB 9866, contains the pchACXF gene cluster, its genes have been sequenced and annotated, and is readily available. If this gene cluster could be inserted into and expressed by a bacterial species that is as manipulable as Escherichia coli, it could become an effective tool for the bioremediation of p-cresol pollution.

Bacillus sp.

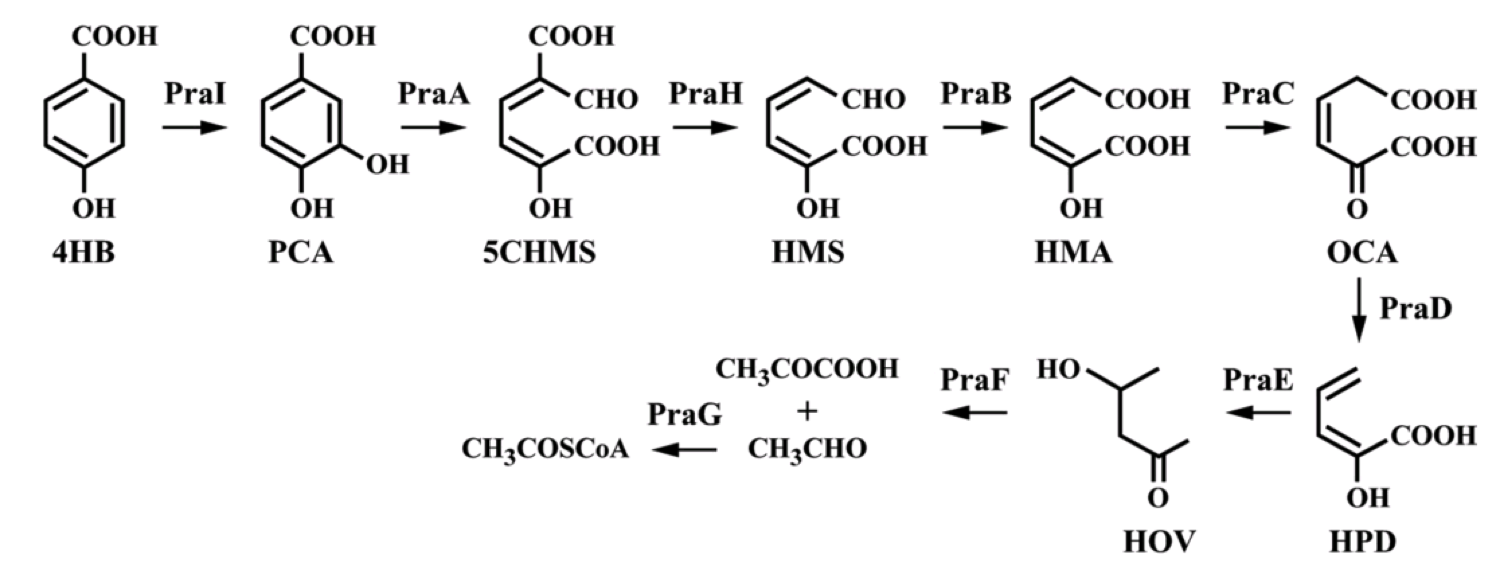

To create a self-sufficient bioremediation tool for p-cresol, the pch cluster will be accompanied by the pra cluster. This second gene cluster encodes for several enzymes that degrade the end product of the pch gene cluster, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, down a pathway that results in the formation of acetyl coenzyme A and pyruvate, which then feed into the citric acid cycle for energy production and cell growth (Crawford, 1975). The praABEGFDCHI gene cluster from the Bacillus sp. strain JJ-1b has been successfully expressed in E. coli, its genes sequenced and annotated, and is readily available (Kasai et al., 2009). A functional E. coli bacterium containing both the pch and pra gene clusters could be able to survive on p-cresol as its sole carbon source. It should be noted, however, that the pra plasmid is not necessary for deodorization of p-cresol. If successfully expressed, the pch plasmid alone would degrade p-cresol to the effectively odorless intermediate, p-hydroxybenzoic acid.

Clostridium difficile

p-Cresol has one final element of interest to humans: it is secreted by the dangerous microorganism Clostridium difficile when forming an infection in the intestine, which is common as a hospital acquired infection and can be fatal. The p-cresol secreted by C. difficile is toxic to almost all other microbes in the intestinal flora, severely disrupting gut function and allowing C. difficile to flourish in the absence of others (Dawson, Stabler, & Wren, 2008). An organism that could efficiently degrade the p-cresol being secreted might be able to restore gut function and inhibit the progression of the infection.

Strategy

Plasmid Design

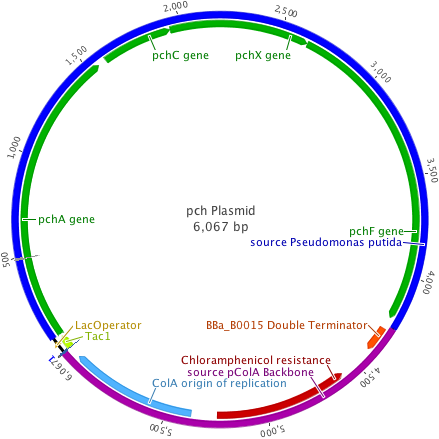

The pch plasmid was designed to insert the 4.2kb pchACXF gene cluster into a backbone vector containing the pColA origin of replication, chloramphenicol resistance, and a double terminator from the Registry of Standard Biological Parts. In addition, the hybrid trp/lac promoter, or Ptac promoter system, was built in using ultramer oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies).

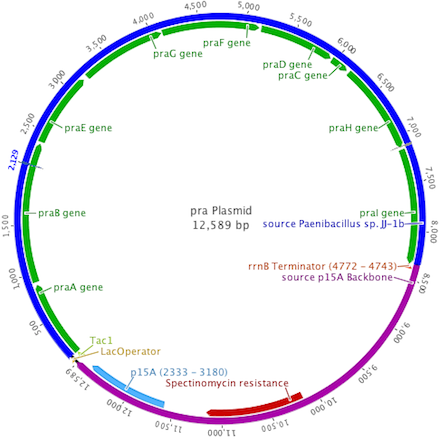

The pra plasmid was designed to insert the 8.3kb praABEGFDCHI gene cluster into a backbone vector containing the p15A origin of replication, spectinomycin resistance, and a single terminator. Transcription of pra was controlled by the Ptac promoter system.

The plasmid backbones were chosen due to their medium plasmid copy number (20-30), strong hybrid promoter with IPTG inducible expression, and a multiple antibiotic resistance selection scheme allowing for better cotransformant selection.

Plasmid Assembly

In order to construct these plasmids, the organisms P. putida NCIMB 9866 and Bacillus sp. JJ-1b were ordered from the repositories NCIMB and ATCC, respectively. Both backbones were obtained from existing samples. After being revived, genomic DNA was extracted from both organisms and purified (Invitrogen). The pchACXF gene cluster was amplified as one fragment using a standard PCR reaction with a genomic DNA sample and Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs). The praABEGFDCHI gene cluster was split into three fragments and amplified separately as praABE, praGFD, and praCHI using a standard PCR reaction with a genomic DNA sample and Phusion polymerase. Amplifications were roughly checked for success by agarose gel electrophoresis, comparing the amplified DNA’s length against a ladder. Gels were recorded using a gel imager system, and then the amplified DNA was gel extracted (Invitrogen). After gel extraction, the purified DNA’s concentration was checked using a Nanodrop ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

The plasmids containing the synthetic pch and pra operons were both constructed using Gibson isothermal assembly (Gibson et al., 2009). Primers were designed to create homology overlaps of approximately 35-45 base pairs in adjacent fragments and introduce synthetic sequences, such as the Ptac promoter system, where necessary. Purified fragments were placed in an aliquot of Gibson assembly mix and incubated at 50ºC for one hour. After plasmids were Gibson assembled, they were desalted on filters (Millipore), and then transformed by electroporation into TOP10 electrocompetent E. coli cells (Invitrogen).

After transformation, cells were recovered in Super Optimal Broth with 20mM glucose, and then spread onto LB agar plates with chloramphenicol antibiotic for the pch transformants, and LB agar plates with spectinomycin antibiotic for the pra transformants. From these plates, if there was any growth, individual colonies of varying characteristics were selected and a colony PCR performed using each pair of primers that were used to originally amplify the fragments of the plasmid.

After each colony was picked, the pipette tip used to pick it was dropped in a test tube containing 4mL of LB and placed in a shaking incubator. The resulting amplified DNA from the colony PCR reaction was checked for length with agarose gel electrophoresis and recorded with the gel imager. Any colonies that passed the gel electrophoresis test for length were recovered from their test tubes, a sample was preserved in a frozen stock, and purified plasmid extracted for Sanger sequencing.

Assays

In order to assay if the synthetic operon is functioning correctly, the pch fragments were assembled and have been transformed into the E. coli strain BW25113 ∆tnaA, which is a single gene knockout mutant with the gene coding for the tryptophanase enzyme removed (Baba et al., 2006). Tryptophanase breaks down the amino acid tyrosine into indole, pyruvate, and ammonium. With the tryptophanase gene intact, the production of indole is responsible for the characteristic fecal odor of E. coli. However, the BW25113 ∆tnaA strain does not produce indole, and therefore serves as an ideal chassis for a deodorizing construct because it is odorless. The pch and pra gene clusters will likely need to be refactored to function properly, replacing native Pseudomonas and Bacillus ribosome binding sites with those of E. coli (Quandt et al., 2013).

An ideal, albeit qualitative, experiment would be to cotransform both the pch and pra plasmids into a BW25113 ∆tnaA chassis and grow it in Davis and Mingioli (DM) minimal media supplemented only with p-cresol as a carbon source and no glucose. If the synthetic operons function as intended, the cells should be odorless before adding p-cresol, and when p-cresol is added, there should be a new, distinct malodor. Growth of the cells should result in the removal of some or all of the malodor.

A more quantitative assay will involve using ultraviolet-visible absorbance spectroscopy on the media supernatant of centrifuged cells grown in minimal media at wavelengths shown to be absorbed by p-cresol and its degradation intermediates. Further confirmation could be achieved by high performance liquid chromatography.

Directed Evolution

We are currently running a directed evolution experiment to evolve an E. coli chassis that can thrive at the highest concentrations of p-cresol possible. By implementing a strong selection pressure for survival at increasing p-cresol concentrations, mutations that improve fitness in a p-cresol saturated environment would be selected for.

The experiment began with the “odorless” and kanamycin resistant BW25113 ∆tnaA strain, grown in LB overnight and streaked out on an LB agar plate with kanamycin to select individual colonies for the three cell lines. Each selected colony was then inoculated in a flask with 10mL liquid DM media at a 500 mg/L glucose concentration. On the first day, each cell line was supplemented with p-cresol at concentrations of 2mM, 3mM and 4mM from a working stock of 0.5M p-cresol in ethanol solution along with a control flask with media and the lowest concentration of p-cresol used. After every day’s culturing , the lines were grown at 37º C in a shaking incubator at 200rpm for 24 hours, then transferred to a new flask by a 1:1000 dilution of 10µL of cells into 10mL of new minimal media.

References

- Antoine, P., Taillieu, X., & Thonart, P. (1997). The Degradation of L-Tyrosine to Phenol and Benzoate in Pig Manure. Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals (pp. 707–717).

- Baba, T., Ara, T., Hasegawa, M., Takai, Y., Okumura, Y., Baba, M., Datsenko, K. A., et al. (2006). Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Molecular Systems Biology, 2, 2006.0008.

- Crawford, R. L. (1975). Novel pathway for degradation of protocatechuic acid in Bacillus species. Journal Of Bacteriology, 121, 531–536.

- Dawson, L. F., Stabler, R. a, & Wren, B. W. (2008). Assessing the role of p-cresol tolerance in Clostridium difficile. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 57(Pt 6), 745-749.

- Gibson, D. G., Young, L., Chuang, R.-Y., Venter, J. C., Hutchison, C. A., & Smith, H. O. (2009). Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nature Methods, 6(5), 343–345.

- Jõesaar, M., Heinaru, E., Viggor, S., Vedler, E., & Heinaru, A. (2010). Diversity of the transcriptional regulation of the pch gene cluster in two indigenous p-cresol-degradative strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens. FEMS Micriobiol Ecol, 72(3), 464-475.

- Kasai, D., Fujinami, T., Abe, T., Mase, K., Katayama, Y., Fukuda, M., & Masai, E. (2009). Uncovering the protocatechuate 2,3-cleavage pathway genes. Journal of Bacteriology, 191(21), 6758–6768.

- Mathus, T. L., & Miller, W. (1995). Anaerobic biogenesis from L-tyrosine of phenol and p-cresol. Fuel, 74(10), 1505–1508.

- Quandt, E. M., Hammerling, M. J., Summers, R. M., Otoupal, P. B., Slater, B., Alnahhas, R. N., Dasgupta, A., et al. (2013). Decaffeination and Measurement of Caffeine Content by Addicted Escherichia coli with a Refactored N-Demethylation Operon from Pseudomonas putida CBB5. ACS synthetic biology, 2(6), 301–307.

- Zahn, J. A., Dispirito, A. A., Do, Y. S., Brooks, B. E., Cooper, E. E., & Hatfield, J. L. (2001). Correlation of Human Olfactory Responses to Airborne Concentrations of Malodorous. J. Environ. Qual., 30(April), 624–634.

"

"