Team:Groningen/Project/Silk

From 2013.igem.org

Spider Silk

Spider silk is a biomaterial with great potential. On one hand it has incredible high tensile strength combined with elasticity, which makes spider silk as strong as steel and tougher than kevlar[1]. On the other hand spider silk also has some peculiar medical properties. Foremost the fact that spider silk (and silk in general) does not cause a strong immune response in the human body[7]. Immune response obviously being one of the major concerns when placing implants inside patients, so our iGEM team saw a great opportunity to combine the spider silk with the implants.

Background

There are many arthropods that have the ability to produce silk, most popular being the Bombyx mori silk worm used in the production of silk for clothing. However the spider easily takes the crown in terms of applications. The spider uses its silk as their Swiss Army Knife, some of these uses include, spinnig webs for catching preys, Dragline's for better movement, and for reproduction [2]. Over the 400 million years of evolution the silk is optimized in many aspects. Like with many fascinating phenomena from nature, humans have learned to utilize the spider webs. The Nephila spiders in tropical rain forests (of Papua New Guinea) have powerful webs to catch flying birds, and ancient cultures have used these webs for fishing purposes[13].

|

The medical properties of spider silk have been known for a long time; there are many records of uses throughout history.

The oldest known application of a spider web dates back to from Ancient Greece were it was used as wound dressing[13]. Some other historical mentions date from around 1600. In the Polish book ‘With Fire and Sword’:

‘ “This is nothing, nothing at all” said he, feeling the wounds with his fingers. “He will be well to-morrow. I will take care of him. Mix up bread and spider-webs for me! ’

And in the famous Shakespearian comedy ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’:

“I shall desire you of more acquaintance, good master cobweb,

If I cut my finger, I shall make bold of you.”

|

Apparently the medical properties of spider webs have been known for a long time. Its use as wound cover improves the recovery without causing problems. What is it that gives the spider silk such excellent healing properties?

Biomedical properties

Normal cells need a scaffold to adhere to. If there is a wound the tissue is repaired very slowly, and only after that the cells from the wound are able to completely recover. When a wound is covered with a good biomedical material, the cells will start to spread, proliferate and differentiate more quickly. On an unsuitable material, the interaction can lead to immune responses and cell death.

Spider silk is suitable as biomedical material because:

- It has no toxicity<[3][4][5]. Short-term and long-term test with various cell lines have given no indication of toxicity.

- No/low immune response[7][8][9]. Different types of cells were examined for immunological response to silk. One study compared collagen, which is used as biomaterial for coating, to silk. The results favoured silk, and deemed silk as being biocompatible[7].

- No inflammation. The body will not detect the silk as a foreign material, as it consists of a smooth protein layer.

- Cell adherence[6]. This depends on the processing of the silk. With small modifications (for instance, genetic addition of an RGD motif) cell adhesion can be improved, to stimulate tissue recovery of a wound. However, for the use of implants, cell adhesion is undesired, as fibrosis can occur.

- Biodegradable. Spider silk has a slow biodegradability, which is useful for medical applications.

- Elasticity and mechanical properties. The spider silk material is strong and stable material. The elasticity of a biomedical material has shown to influence cell growth and proliferation, and therefore the flexible and adjustable spider silk is very potent.

- Does not swell. Due to the nature of the protein it is both hydrophilic and hydrophobic, the latter preventing any major uptake of water.

- No bacterial or fungal degradation[7]; this is credited to the long evolution. One can imagine that if the base of a spiders nature, its web, would be easily torn apart by the hundreds of bacteria and fungi around, then they would not have gotten this far. The silk typically has a very flat surface that does not allow cells to grow on it very easily, nor be identified by antibodies.

|

| Figure 2, Overview of biomedical advantages |

Studies performed with coated implants in mice and pigs support these medical properties. Also spider silk coated breast implants are tested in preclinical trials, and have so far shown promising results[10].

| Biomedical material | Spider Silk | Collagen |

|---|---|---|

| No inflammation | 25px | 25px |

| No immune response | 25px | 25px |

| High tensile strength | 25px | 25px |

| Low bacterial adherence | 25px | |

| Stable, slow-degrading | 25px | |

| No disease transmission | 25px | |

| Promotes cell adherence | 25px | 25px |

| Promotes regeneration | 25px | |

| Table 1: Comparison of spider silk with another biomedical material: collagen. Collagen is a mammalian fibrous protein, and in many respects similar to spider silk. However, there are still limits to collagen, and some aspects where spider silk is superiour[8] | ||

Spider silk is our choice to approach the problems of medical implants. However, so far no large scale production of spider silk is achieved, and production, purification and processing are challenging. Why is the production of the spider silk protein so difficult? How can we make a coating from the spider silk?

Silk protein

The spider silk protein is a fibrous protein. It does not have a folded state on its own; it is able to assemble (multimerize) with multiple identical proteins to form the silk material. The protein consists of roughly 3 motifs, each featuring a particular secondary structure in the assembly (table 2).

| Amino acid sequence | Secondary structure | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| AAAAAAAA | β-sheet | Tensile strenght, rigidity, hydrophobicity |

| GPG(AG)QQ / GPG(SGG)QQ / GPGGX | β-spiral / β-turn | Extensibility, elasticity |

| GGX | 310 helix | Link, alignment, flexibility |

Depending on the processing of the silk proteins the material can have a degree of these secondary structures, defining its properties (table 2). The processing inside a spider is still not completely elucidated. The spider has a special duct in which many processes take place, among which are drastic decrease in pH, and change in salts[14]. The latter is also utilized in the processing of recombinant spider silk. It was found that kosmotropic ions ("salting-out"), such as phosphate and potassium, induce beta-sheet formation and thus rigidity and hydrophobicity of the silk.

This is because the assembly of the silk proteins is induced by depletion of solvent (generally water). Any action or substance that can contribute to the removal of water, can also contribute to polymerization and structure of the spider silk. Often methanol is used to improve the formation of beta-sheets[14].

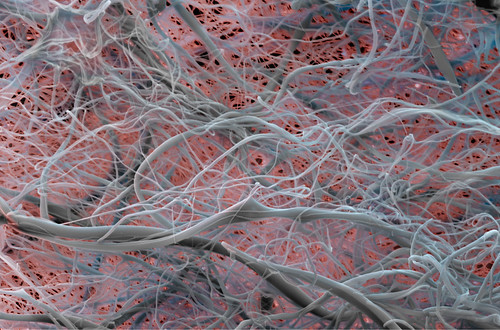

In order to make our spider silk coating material, a large amount of these proteins are required. The protein has a very repetitive nature (fig. 2), with these motifs (table 2) recurring within the protein. This makes is difficult to translate the protein, because it requires presence of the same tRNAs in a large amount. This can be solved with codon optimization. See codon optimization at the modelling section for the explanation of this approach.

|

| Figure 2, Major ampullate Spidroin 2 (MaSp2) from Argiope aurantia |

References

[1] Griffiths, J. R., and V. R. Salanitri. "The Strength of Spider Silk." Journal of Materials Science 15.2 (1980): 491-96[2] Foelix, Rainer F. Biology of Spiders. New York: Oxford UP, 1996.

[3] Liu, Tie-lian, Jing-cheng Miao, Wei-hua Sheng, Yu-feng Xie, Quan Huang, Yun-bo Shan, and Ji-cheng Yang. "Cytocompatibility of Regenerated Silk Fibroin Film: A Medical Biomaterial Applicable to Wound Healing." Journal of Zhejiang University SCIENCE B 11.1 (2010): 10-16

[4] Allmeling, Christina. "Use of Spider Silk Fibres as an Innovative Material in a Biocompatible Artificial Nerve Conduit." Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 10.3 (2006): n. pag.

[5] Acharya, C., B. Hinz, and S. Kundu. "The Effect of Lactose-conjugated Silk Biomaterials on the Development of Fibrogenic Fibroblasts." Biomaterials 29.35 (2008): 4665-675. Print.

[6] Seo, Y. K., H. H. Yoon, Y. S. Park, K. Y. Song, W. S. Lee, and J. K. Park. "Correlation between Scaffold in Vivo Biocompatibility and in Vitro Cell Compatibility Using Mesenchymal and Mononuclear Cell Cultures." Cell Biology and Toxicology 25.5 (2009): 513-22

[7] Meinel, L., S. Hofmann, V. Karageorgiou, C. Kirkerhead, J. Mccool, G. Gronowicz, L. Zichner, R. Langer, G. Vunjaknovakovic, and D. Kaplan. "The Inflammatory Responses to Silk Films in Vitro and in Vivo." Biomaterials 26.2 (2005): 147-55

[8] MacIntosh, Ana C., Victoria R. Kearns, Aileen Crawford, and Paul V. Hatton. "Skeletal Tissue Engineering Using Silk Biomaterials." Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 2.2-3 (2008): 71-80

[9] Panilaitis, B. "Macrophage Responses to Silk." Biomaterials 24.18 (2003): 3079-085

[10] AMSilk GmbH, http://www.amsilk.com/en/products/implant-coating.html, Copyright © 2013 AMSilk GmbH

[11] BASF The Chemical Company, January 26 2011, http://www.flickr.com/photos/basf/5412675961/in/set-72157624601397168, Copyright 2011 BASF

[12] Hayashi, Cheryl Y., Nichola H. Shipley, and Randolph V. Lewis. "Hypotheses That Correlate the Sequence, Structure, and Mechanical Properties of Spider Silk Proteins." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 24.2-3 (1999): 271-75

[13] Scheibel T., ETSI Caminos, "Silk structure, silk protein folding and assembly", http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=vIcMd9BjSFo#t=211

[14] Spiess, Kristina, Andreas Lammel, and Thomas Scheibel. "Recombinant Spider Silk Proteins for Applications in Biomaterials." Macromolecular Bioscience 10.9 (2010): 998-1007

"

"