Team:Greensboro-Austin/MAPs

From 2013.igem.org

Contents |

Mussel adhesion proteins (MAPs)

The mussel is a marine mollusk that lives in the inter-tidal zone on wave washed rocks. To withstand the tidal forces, they must bind themselves to these rocks with their endogenous glue. Mussels have an organ called the foot, which is used to both pull the mussel through terrain and to excrete a structure called the byssus. These byssal threads are made up of collagen and other proteins and are what allow the mussel to attach to surfaces.

The properties of mussel glue make it an attractive target for synthetic improvement; mussel glue allows attachment to many different types of surfaces, both organic and inorganic. It is strong and durable as it is able to withstand the harsh ocean environment. It is made of protein, so it is biodegradable and is environmentally friendly. Most importantly, however, it is biocompatible (non-immunogenic) and—unlike most glues—it works in aqueous environments.

There are several different proteins that make up the byssal threads, but the ones we’re most interested in are the ones that lie at the interface with the surface to which the mussel adheres. These proteins are responsible for the binding to the substrates and therefore have the most potential for use as a glue.

All of the different mussel foot proteins have a percentage of their tyrosines post-translationally modified to a molecule called L-DOPA. It turns out that the proteins closer to the adhesion surface have a much higher L-DOPA content, and in fact the L-DOPA content is linearly correlated with adhesiveness.

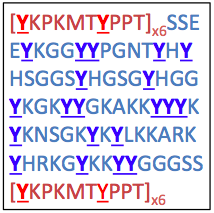

To the right is the sequence of a recombinant mussel adhesion protein, fp-151, that has good adhesive properties. Notably, it has high tyrosine content, denoted by the letter Y.

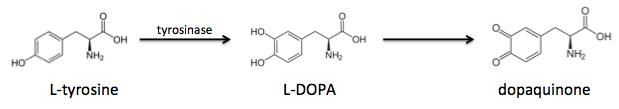

It turns out that tyrosines are critical for adhesion, but first they must undergo tyrosinase-mediated hydroxylation to L-DOPA, which can be further oxidized to dopaquinone:

These modified amino acids contribute to adhesion via two separate mechanisms: L-DOPA interacts non-covalently with inorganic surfaces by chelating metal ions, whereas dopaquinone interacts with organic surfaces through the formation of covalent bonds.

Previous work

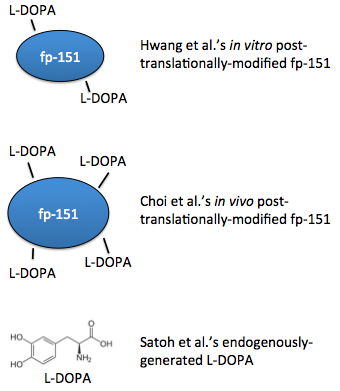

In 2007, a recombinant protein called fp-151 was first produced, which was notable for its lower cytotoxicity than previous recombinant foot proteins. After purifying the protein, tyrosine residues were hydroxylated in vitro with tyrosinase, so the protein was already folded before this modification could occur, possibly limiting access to the tyrosines [5]. Choi, et al. extended this work with a coexpression system, such that the residues were modified in vivo, simultaneously along with translation. These foot proteins had better adhesive properties [6]. Also in 2012, a system to generate L-DOPA from free tyrosine was engineered [7].

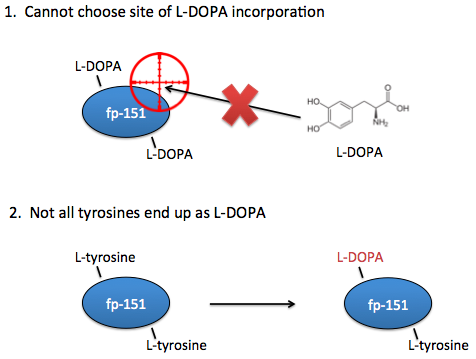

However, these systems are not yet optimal for studying the effects of L-DOPA content on adhesive properties. Ideally, you need the ability to choose exactly which sites that L-DOPA should be incorporated. In current systems, you can only choose where there should be tyrosines.

Additionally, in current systems there is no guarantee that a tyrosine placed at your desired location will even end up as an L-DOPA, so we would also want the ability to know for certain that the residues of interest are in fact L-DOPA and not tyrosine.

Our solution: direct non-canonical amino acid incorporation

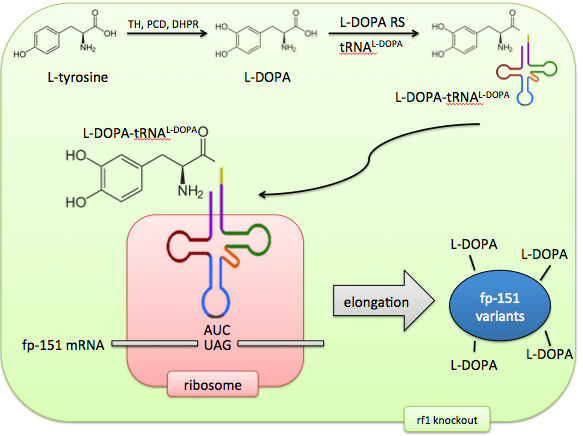

Incorporating the non-canonical amino acid L-DOPA directly would solve these problems of control and predictability. The M. jannaschiitRNA synthetase has been evolved to recognize the non-canonical amino acid L-DOPA by sequential rounds of positive and negative selection. The tRNA’s anticodon loop recognizes the UAG AMber stop codon and therefore this codon is now repurposed to code for a 21st amino acid.

In addition, release factor 1, which normally recognizes this Amber codon, can be knocked out, ensuring no competition between the stop codon’s old effect (termination) and its new effect (L-DOPA incorporation). The result of this system is an expansion of the cell’s genetic code to 21 amino acids, allowing precise control of targeted L-DOPA incorporation.

E. coli as a self-sufficient microbial factory

Our vision is of E. coli as a biosynthetic "factory" able to make complicated products with simple inputs. By giving it the machinery to charge tRNA with L-DOPA, and expanding the genetic code to include L-DOPA, this non-canonical amino acid can be incorporated at rationally targeted locations, generating a library of foot protein variants.

Appropriate with this characterization of self-sufficiency and synthetic capability, these E. coli would not even need to be supplemented with exogenous L-DOPA, as they could continually generate it from intracellular free tyrosine.

Experimental design

A two-plasmid system would be appropriate for our aims. One plasmid would code for a library of fp-151 variants, each containing Amber codons in unique locations and quantities, yielding a diverse set of foot proteins with characteristic locations and numbers of L-DOPA residues. The adhesive properties of these variants would be compared against both in vitro and in vivo tyrosinase-treated foot proteins, which would serve as positive controls.

This plasmid would also contain our L-DOPA biosynthesis cassette, ensuring a continual source of non-canonical amino acid without supplementation.

The second plasmid would code for the synthetase/tRNA pair that is responsible for adding L-DOPA to the genetic vocabulary.

Diversity of Parts

The individual components of this system are derived from a variety of organisms. The foot proteins come from mussels, the genes in the L-DOPA biosynthesis cassette come from mice and humans, and the synthetase/tRNA pair is derived from archaea, and all these components are put in bacteria.

This covers 5 different organisms from all three domains of life, and as such would be a remarkable illustration of synthetic biology!

Results

Future Directions

References

- Deiters A, and Schultz PG. In vivo incorporation of an alkyne into proteins in Escherichia coli. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005 Mar 1;15(5):1521-4.Pubmed PMID: 15713420.

- Mukai T et. al. Codon reassignment in the Escherichia coli genetic code. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 December; 38(22): 8188–8195. Pubmed PMID: 20702426

- Sakamoto et. al. Genetic Encoding of 3-Iodo-L-Tyrosine in Escherichia coli for Single-Wavelength Anomalous Dispersion Phasing in Protein Crystallography.Structure. 2009 Mar 11;17(3):335-44. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.01.008. PubMed PMID: 19278648.

- Liu CC, Schultz PG. Adding New Chemistries to the Genetic Code. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:413-44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. PubMed PMID: 20307192.

- Hwang DS, Gim Y, Yoo HJ, Cha HJ. Practical recombinant hybrid mussel bioadhesive fp-151. Biomaterials. 2007 Aug;28(24):3560-8. Epub 2007 May 3. PubMed PMID: 17507090.

- Choi YS, Yang YJ, Yang B, Cha HJ. In vivo modification of tyrosine residues in recombinant mussel adhesive protein by tyrosinase co-expression in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2012 Oct 24;11:139. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-139. PubMed PMID: 23095646; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3533756.

- Satoh Y, Tajima K, Munekata M, Keasling JD, Lee TS. Engineering of L-tyrosine oxidation in Escherichia coli and microbial production of hydroxytyrosol. Metab Eng. 2012 Nov;14(6):603-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.08.002. Epub 2012 Aug 29. PubMed PMID: 22948011.

"

"