Team:UCL/Modeling/Bioinformatics

From 2013.igem.org

A BIOINFORMATICS APPROACH

Finding New Parts

Bioinformatics creates and enhances methods for storing, retrieving, organising and analysing biological data. We decided to take a completely new approach in our dry lab work and look into bioinformatic approaches to studying Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

The rationale behind this is simple. In order to make a genetic circuit in a synthetic biological construct as effective as possible in a medical application, we may need to target key dysfunctional genes within the problematic biological entity. There are many risk factors for AD and so predicting the key, ‘driver genes’, and the group of proteins with which they interact is invaluable in knowing what we want our construct to produce, in order to mitigate AD. The idea is that bioinformatics work can feed back into synthetic biology, and though we did not have the time to demonstrate this full circle, we feel bioinformatics can have a place in iGEM, helping teams to decide which dysfunctional genes to target in medical projects.

Bioinformatics and Alzheimer’s Disease

Recent progress in characterising AD has lead to the identification of dozens of highly interconnected genetic risk factors, yet it is likely that many more remain undiscovered (Soler-Lopez et al. 2011) and the elucidation of their roles in AD could prove pivotal in beating the condition. AD is genetically complex, linked with many defects both mutational or of susceptibility. These defects produce alterations in the molecular interactions of cellular pathways, the collective effect of which may be gauged through the structure of the protein network (Zhang et al. 2013). In other words, there is a strong link between protein connectivity and the disease phenotype. AD arises from the downstream interplay between genetic and non-genetic alterations in the human protein interaction network (Zhang et al. 2013).

Recent progress in characterising AD has lead to the identification of dozens of highly interconnected genetic risk factors, yet it is likely that many more remain undiscovered ((Soler-Lopez et al. 2011) and the elucidation of their roles in AD could prove pivotal in beating the condition. AD is genetically complex [internal link to neuropathology page], linked with many defects both mutational or of susceptibility. These defects produce alterations in the molecular interactions of cellular pathways, the collective effect of which may be gauged through the structure of the protein network(Zhang et al. 2013). In other words, there is a strong link between protein connectivity and the disease phenotype. AD arises from the downstream interplay between genetic and non-genetic alterations in the human protein interaction network (Zhang et al. 2013).

In all pathologies, the most common way to predict driver genes is to target commonly recurrent genes. However, this approach misses misses rare altered genes which comprise the majority of genetic defects leading to, for example, carcinogenesis and arguably AD. This is partly because alterations in a single protein module can lead to the same disease phenotype. Thus, identification may best be attempted on a modular level. Yet it is also important to note correlation events between modules. Simply put, many rare gene alterations that influence the module they belong to and co-altered modules can collectively generate the disease pathology (Gu et al. 2013).

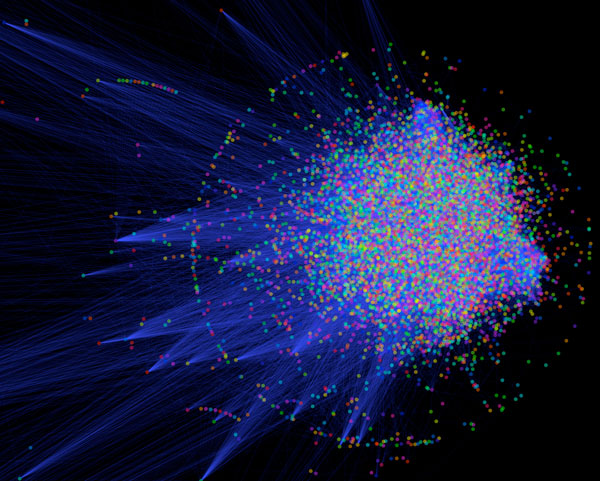

Our Programme

Under the guidance and tutelage of Dr Tammy Cheng from the Biomolecular Modelling (BMM) lab at Cancer Research UK, team member Alexander Bates coded in python a network analysis programme based on a method devised by Gu et al. and originally applied to the study of glioblastoma (brain cancer). The programme tries to reveal driver genes and co-altered functional modules for AD. The analysis procedure involves mapping altered genes (mutations, amplifications, repressions, etc.) in patient microRNA data to the protein interaction network (PIT), which currently accounts for 48,480 interactions between 10,982 human genes. This is termed the ‘AD altered network’, and is searched with the algorithm suggested by Gu et al. (which has been re-coded from scratch).

The programme builds up gene sets, two at a time, starting from two seed genes. These sets are termed 'modules'. Pairs of modules (‘G1’ and ‘G2’ in equation) are assumed to be co-altered if any gene within each module is altered in a proportion of AD sufferers, and genes between the modules are often altered together. For two modules, G1 and G2, we must calculate the probability, P, of observing than the number of the samples in the patient gene expression data that by chance simultaneously carry alterations in both gene sets. The gene expression data originates from post-mortem brain samples.

‘n’ is the total number of patient samples, ‘a’ is the number of patients with alterations in both G1 and G2, ‘b’ is the number of patients with alteration in just G1, ‘c’ is the number of patients with alterations in only G2, and ‘d’ is the number of patients with alterations in neither set. The co-altered score’ S, is defined below. A high score indicates that the two modules tend to be altered together in AD.

Fig.1 depicts the searching algorithm. It searches and builds co-altered module pairs for the gene combinations within them that have the greatest co-alteration scores. In step 1, it methodically choose two seed genes from the AD altered network. The ellipsoids in the diagram denote direct interaction partners for these genes. These are added to the seeds to make temporary module pairs. The dashed line represents co-alteration. In step 2, the co-alteration score for each temporary module pair is calculated. Only the pair with the maximal S score is retained for subsequent searching. This maximal group becomes the new seeds group in step 3. In step 4, temporary modules are again derived, this time from step 3, and the maximum score is kept. In step 5, it must determine whether or not this group of genes is going to continue to expand. Each new addition save for the original two starting seeds is removed and S is recalculated. If in one of these configurations S becomes smaller, we loop through steps 3 to 5 again. Otherwise, if all combinations equate to the S value of the gene groups chosen from step 4, the process stops, having assumed that we have reached maximal module size for the two starting seeds.

In other words, we try to build up gene sets within a module as large was we can, whilst with each new addition increasing the co-alteration score.

The P-values of the co-altered modules this algorithm identifies are modified by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure and those with an FDR < 10% are kept. If a pair of co-altered modules share more than 50% of their genes with another pair, the one with the lowest S score is discarded. We should be left with modules that frequently exhibit significant co-alteration in AD patients, and their gene products are therefore likely to be biochemically significant in the disease state.

Results

Originally we planned, as previously suggested, to use the entirety of the human interactome to create an AD interactome and then run our programme in such a way as to build modules from this interactome. However, the estimated run time of the programme over-shot the iGEM 'wiki freeze' deadline. Therefore, we used the expression data for 311 hub genes, whose proteins are points of high connectivity in the human interactome, across 62 modules defined by Zhang et al., and searched for the hub genes combinations that produced the greatest co-alteration scores. The 62 modules are named after colours.

Module groups:

Module functions:

Hub expression data:

Module matrix:

Fig.1 Histogram showing the frequency of gene sets by co-alteration score. |

|---|

We used the output of our programme to produce a histogram, which shows that the frequency of gene combinations falls exponentially with increasing co-alteration score This suggests that a significant few combinations are regularly co-altered in Alzheimer's disease, in modules that may help drive the disease state. Because we are only looking at which hub genes within modules, we are most interested in what modules are co-altered in the high score end of the histogram, and not the hub genes specifically.

Below, Fig.2 shows the twenty gene set pairs between two modules, which yielded the greatest co-alteration score. The module pair with the highest score, and that recurs most frequently in the top twenty, are the 'Khaki' and 'Honey Dew' modules. The most enriched functional category of the khaki module is the biosynthesis of a neurotransmitter called GABA. GABA is responsible for neuronal excitability and muscle tone. The Honey Dew module is primarily involved in muscle contraction, though the hub genes AHCYL1 and C9orf61 are thought to be involved in inositol signaling and are possibly associated with another brain condition, bi-polar disorder. However, since the gene expression data is from generally older patients, given the profile of AD, these muscle associated modules may be altered together because of changing muscle usage with age (there is no muscle in the brain but this may represent brain cell structural integrity). Both of these modules have almost 100% of their total brain gene expression in the prefrontal cortex, and area known to be heavily impacted in AD, causing cognitive and intellectual damage. This suggests that our genetic circuit could be adapted to target signaling mechanisms in this area.

Fig.2 Table of the top 20 gene combinations and their modules by co-alteration score. |

|---|

| Module Name and Gene Set | Module Name and Gene Set | Co-alteration Score |

|---|---|---|

| Khaki | Honey Dew | 20.3899639423 |

| SLC15A2, FXYD1 | AHCYL1, C9orf61 | |

| Khaki | Honey Dew | 19.7292263621 |

| GJA1, FXYD1 | RFX4, AHCYL1, C9orf61 | |

| Khaki | Honey Dew | 19.3733729778 |

| GJA1, FXYD1, ATP13A4 | C20orf141, RFX4, AHCYL1, DGCR6 | |

| Turquoise | Cyan | 18.9953518132 |

| DYNC2LI1, CIRBP, ACRC, RBM4 | Contig47252_RC, IFITM2, CDK2 | |

| Turquoise | Cyan | 18.8148253456 |

| DYNC2LI1, CIRBP, ACRC, RBM4 | ENST00000289005, Contig47252_RC, IFITM2, CDK2 | |

| Khaki | Honey Dew | 17.6975602146 |

| GJA1, FXYD1, SLC15A2 | RFX4, AHCYL1, C9orf61 | |

| Green 4 | Yellow 3 | 17.5748504612 |

| RRM2, NM_022346, FAM64A | OR4F5, GRAP, XM_166973 | |

| Turquoise | Wheat | 17.4863557432 |

| DYNC2LI1, RBM4 | AF087999 | |

| Green 4 | Yellow 3 | 16.9529019631 |

| HMMR | OR4F5, GRAP | |

| Green 4 | Yellow 3 | 16.9529019631 |

| HMMR | OR4F5, GRAP, CRYBA2 | |

| Turquoise | Wheat | 16.7809549575 |

| CIRBP, RBM4 | AF087999 | |

| Green 4 | Yellow 3 | 16.644270469 |

| RRM2, NMMR, FAM64A | KRTHB4, GRAP, XM_166973 | |

| Turquoise | Cyan | 16.474246077 |

| DYNC2LI1, CIRBP, ACRC, RCC1, RBM4 | Contig47252_RC, IFITM2 | |

| Turquoise | Cyan | 16.462009998 |

| DYNC2LI1, CIRBP, ACRC, RCC1, RBM4 | Contig47252_RC, IFITM2, CDK2 | |

| Forestgreen | Cyan | 16.4327971819 |

| IFITM3, CSDA | CSDA | |

| Turquoise | Cyan | 16.3777786794 |

| DYNC2LI1, CIRBP, ACRC, RCC1, RBM4 | ENST00000289005, Contig47252_RC, IFITM2 | |

| Khaki | Honey Dew | 16.2710849426 |

| FXYD1, ATP13A4, SLC15A2 | AHCYL1, C9orf61 | |

| Khaki | Honey Dew | 16.2510456217 |

| FXYD1, ATP13A4 | DGCR6, AHCYL1, C20orf141, C9orf61 | |

| Gold 2 | Honey Dew | 16.2095249953 |

| TUBB2B, NM_178525 | AHCYL1, C9orf61 | |

| Khaki | Honey Dew | 16.0377287109 |

| SPON1, FXYD1, SLC15A2 | AHCYL1, C9orf61 |

The second highest scoring module pair, and the second most frequent in the top twenty, are 'Turquoise' and 'Cyan'. The former is primarily involved with NAD(P) homeostasis, and so is significant in cells' metabolism, while the genes in the later mainly play a role in vasculature development. This suggests that co-alteration in genes involved within these two modules could impact cell vitality and trophic support and help cause AD. This suggests that our circuit could be improved by being adapted to help maintain general cell health and energy supply in the brain.

The third highest scoring module pair, and the third most frequent in the top twenty, are 'Green 4' and 'Yellow 3'. Green 4 is involved in cell cycle regulation, and area that has already been targeted by our circuit, which produces BDNF to help avoid chromosomal division in the neurons of AD patients. Yellow 3 is associated with the peripheral nervous system. Co-alteration here may again be indicative of gene expression changes with age, and its link with Green 4 may suggest that this is to do with a deficiency in cell division, regeneration and growth, but this is not directly related to AD, although hub genes like GRAP do play a role in cytoplasmic signaling in cells including neurons and glia, This suggests that our circuit could be improved by being adapted to help maintain general cell health and energy supply in the brain.

Other module pairs that feature in the top twenty include 'Wheat' and 'Turqouise', 'Forestgreen' and 'Cyan' and 'Gold 2' and 'Honey Dew'. Wheat is involved in protein folding and responses to unfolded and mis-folded protein. This is significant because incorrectly formed and folded amyloid is strongly associated with the progression of AD. This is something out circuit already seeks to address, but by targeting elements of the 'Wheat' module and similar modules it could aim to avoid mis-creation in the first place, and the nucleation of other mis-folded proteins. Forestgreen is involved in immune functions, which implicates microglia and the cellular response to inflammation in neurons - factors our circuit already tries to help address by acting to prevent neuroinflammation. Its association with Cyan could imply that negative inflammatory effects may be inked with brain vasculature in AD. Gold 2 is associated with the cytoskeleton and axonal cytoskeletal control.In AD, the formation of plaques and protein tangles disrupts the cytoskeleton and perturb axonal connections, engendering cell death. Our circuit tries to target this already by removing the plaques, but perhaps a future improvement should to be to create an element capable to supporting a healthy cytoskeleton or able to remove cytoskeletal protein tangles. Its association with Honey Dew, however, could point to unusual gene expression in this module being due to the lessened use of muscle in old age.

"

"