Team:Groningen/Project

From 2013.igem.org

Contents |

Introduction:

Silk is a natural protein fibre that is known for its use in textiles. The best know silk comes from the silk moth pupa but other arthropods are also capable of producing silk. One of the arthropods well know for its silk is the spider.

Spider Silk is amazing but currently large scale production is impossible. Various techniques to produce spider silk are being considered and one of them is letting bacteria produce the silk. This idea is promising although one of the main challenges is the low production rate of bacteria.

Silk has some really nice attributes and some of these attributes are feasible for medical devices. Silk is an inalergic biomaterial and it is proven to enhance the healing process when it is used as a cover of implants, allowing for better acceptance by the human body (vepari & kaplan 2007, Mandal et al 2012).

Though there has been some succes in producing silk in bacteria (Xia et al 2010), currently the bacteria needs to be killed in order to extract the silk. In this project the plan is to have the bacteria secrete the silk so that it can live and continue to produce more silk. Also the the design needs to be made such that most of the silk production happens at the required location to compensate for the low production volume.

Project goal:

The goal of this project is creating a bacteria that produces silk proteins and secreets it for the purpose of attaching it on the surface of an implant. For this the plan is to create a bacillus subtilis that can produce and secreet a silk like protein. Additionally, it is attempted to make the bacillus move to the location where the silk is needed. This way there should be fewer problems caused by the low silk yield. There are different methods of directing the movement. The one that will be aplied in this project is the use of temperature as the attractant/repellant. The bacillus should move away from the cold and towards the heat. This way the bacillus can move toward the implant and there it can produce and exceed silk.

Silk expression:

For the silk expression the bio-brick from the Utah team of 2012 is used. They successfully created a gene for the production of a silk like protein based on the spider silk gene. This gene was expressed in E. coli. In this project the gene is placed in bacillus suptilis. For variation, strep tacs are added to the silk to allow for binding to objects. This should allow for a coating of, among others, medical implants.

Silk secretion:

For the silk to be secreted the sec pathway is used. A signal sequence in the vector is used to secreet the proteins. This allows the bacillus to recognize the protein as an object that needs to be moved outside of the cell. (Pohl and Harwood)

The first Signal sequences that will be attempted are MotB FliZ EstA and LytB.

Abstract

The unique properties of silk have provided it with a utility that goes far beyond that of any other natural fibers known to man. Its amazing mechanical properties, 'silky smooth' softness, and bio-compatibility, has led to applications ranging from from simple clothing to high tech biomedical devices.

The industry from which silk is obtained, however, is less than ideal. Scientists have therefore begun to design silk-producing micro-organisms. The 2012 iGEM team from Utah have indeed successfully designed BioBricks for this very purpose. However, these micro-organisms remain inadequate in the secretion of silk, which is a major limiting factor on the range of potential biosynthetic designs and applications.

Our goal is to solve the secretion issue and to use it for the formation of a silk biofilm. The beauty of such a biofilm can be attributed to the properties of silk, and to the fact that any imaginable shape of seamless silk could be created since the biofilm grows in such a way as to fit its mold. We will be exploiting these properties to coat biomedical prosthetic devices, with the goal to prevent infections, and hence to prevent the required operations in dealing with such infections.

Silk

small intro here

The origin of silk

Ancient Chinese legend has it that a princess named Xi Ling Shi, who was having a relaxing afternoon under a Mulberry tree, first discovered silk 4500 years ago when a cocoon suddenly fell in her tee. After some time, Xi Ling Shi extracted a silk thread from her still steaming cup of thee, and unraveled the secret of silk along with its cocoon.

The knowledge that silk could be extracted from insect cocoons was closely guarded, and harsh conditions were set (the penalty of death) to anyone who was caught smuggling the eggs or cocoons. By such means, China realized a two thousand year monopoly of the silk industry, which was, according to yet another legend, put to an end when a Chinese princess smuggled moth eggs and mulberry seeds as a gift for her future husband. Subsequent to the princesses betrayal, the secret of silk was still kept secret from the west for another good thousand years or so, as it was only in the 12th century ACE that sericulture (the production of silk) began to develop.

Silk has thus inspired many legends and myths. Whether the stories are true or not, it is a fact that the discovery of silk has had world-wide impacts on culture, economy, development, and trade due to its much desired properties.

Princess Xi Ling Shi. [3]

The properties of silk

The unique properties of silk are a result of its highly constant and repetitive amino-acid structure. The sequence of amino-acids determines what secondary structures will arise, and thus the final preferred protein conformation. The secondary structures may be beta sheets, beta-spirals, and beta-helices, of which the sheets realize the silk's amazing tensile strength, and the spirals and helices its elongation.

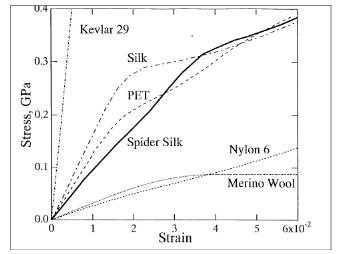

In the figure below a stress-strain diagram can be found (Frank K. Ko, et at. 2001) where Clavipus spider silk is compared to, Kevlar 29, normal silkworm silk, PET (polyethylene terephthalate), Nylon 6, and Merino wool. The stress-strain diagram relates the degree of deformation to the amount of energy absorbed.

When used as clothing, silk has many beneficial properties. Its smooth, compact surface feels and looks nice, and it enables easy removal of dirt. It is a bad conductor of heat, making it cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Furthermore, it has a water absorption efficiency similar to that of wool, and is resistant to insects and mildew.

A final general property of silk it that it can be integrated with the human body - it will not induce an immune response - potentially making it an ideal choice for many biomedical applications. Its compatibility extends to the gastrointestinal tract, that is, it is even safe to eat!

The production of silk

The farming of silk is an arduous, time consuming, and costly process. Although a single cocoon may produce up to one mile of filament, 4 to 8 filaments are needed to produce a single thread, and approximately 5500 cocoons are needed for one kilogram of silk. Eight fully grown mulberry trees would have been needed for this single kilogram, and 48 hours of man-labor required to hand-reel it. Finally, the caterpillars required a full month to mature and three to five days to spin their cocoons, after which they were brutally boiled alive. Harvesting the more desired and rare silk from spiders requires an even more labor-extensive process. Each thread actually has to be pulled individually by hand from the spiders gland - needless to say, not a viable business plan!

The silk industry itself has undergone very little development over the past few millennia. Indeed, the manner in which it is obtained follows the very same process as that of princes Xi Ling Shi's initial discovery, albeit at a much grander scale with more specialized equipment. Scientists have therefore begun to design their own silk producing organisms [2]. Moreover, the 2012 iGEM team from Utah successfully designed the first spider-silk producing Biobricks for Escherichia coli (for more information, please visit their [https://2012.igem.org/Team:Utah_State wiki]). Such advancements are needed to provide the industries and manufacturers with sufficient silk proteins for their applications.

Applications for silk

Silk's journey as a product began as luxurious clothing reserved exclusively for the emperor subsequent to its initial discovery. As the sericulture developed, however, it was soon adopted by all classes of society. New applications were discovered, and it was spun into many different products; fishing lines, musical instruments, and bowstrings to name a few. It's utility and value were also recognized by other kingdoms, and a world-wide, ever increasing demand for the material began. Indeed, the western demand for silk was so great, that the main set of trade routes between Europe and Asia became known as the Silk Road.

.... Nowadays, the variety of silk applications is even more extensive; bullet-proof clothing, all sorts of ropes and cables, artificial tendons and ligaments, bandages, sewing thread, seat belts, parachutes, biodegradable bottles, and much more.....

References

[1] Frank K. Ko, et al, (2001). "Engineering properties of spider silk". MRS Proceedings, vol. 702

[2] Charlotte Vendrely & Thomas Scheibel, (2007). Biotechnological production of spider-silk proteins enables new applications. Macromol. Biosci, vol 7, pp 401-409.

[3] [http://www.chinancient.com/chinese-ancient-four-beauties-xi-shi/xi-shi-02-2/ Current online source.] Waiting for author for more details.Charu Vepari and David L. Kaplan, Silk as biomaterial, Progress in polymer science (2007), Vol. 32 No. 8-9, pp. 991-1007.

Biman B. Mandal, Ariela Grinberg, Eun Seok Gil, Bruce Palinaitis and David L. Kaplan, High-strength silk protein scaffolds for bone repair, Proceedings of the National Acadamie of Science of the United States of America (2012),Vol. 109 No. 20, pp. 7699-7704.

Xiao-Xia Xia, Zhi-Gang Qian, Chang Seok Ki, Young Hwan Park, David L. Kaplan, and Sang Yup Lee, Native-sized recombinant spider silk protein produced in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli results in a strong fiber, Proceedings of the National Acadamie of Science of the United States of America (2010), Vol. 107 No. 32, pp. 14059-14063.

Susanne Pohl and Colin R. Harwood, Heterologous Protein Secretion by Bacillus Species: From the Cradle to the Grave, Advances in Applied Microbiology (2010),Vol. 73, pp. 1-25.

"

"