Team:Dundee/Project/MopMaking

From 2013.igem.org

Making the Mop

ToxiMop – What it is & how it works

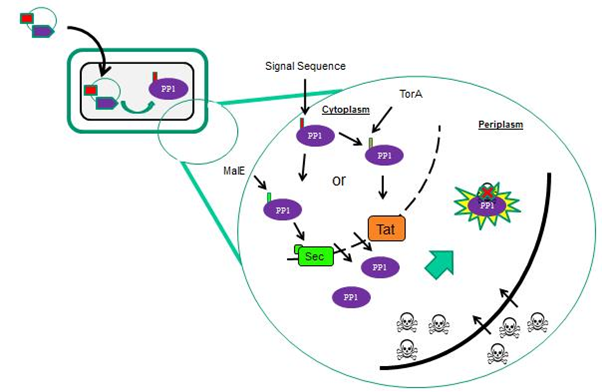

We aimed to engineer two bacterial chassis with the ability to clean up microcystin from contaminated water. These strains were engineered to express the human protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), to which microcystin binds covalently.

We used two different chassis for the expression of PP1: Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. These two organisms were selected as they have different cell envelope organisations, which allowed us to take two different approaches to developing our mop. On the one hand B. subtilis is Gram-positive, meaning that it has a single cell membrane. E. coli on the other hand is Gram-negative, and is therefore double-membraned, having both an inner, or cytoplasmic membrane, and an outer membrane. These two membranes surround a compartment called the periplasm.

In order to increase the probability of microcystin/PP1 interactions, we targeted PP1 toward the outer surface of the cells. In E. coli we targeted PP1 to the periplasm (Fig 1) and in B. subtilis we targeted PP1 to the extracytoplasmic side of the membrane. This localisation of PP1 is mediated by supplying the protein with different N-terminal signal sequences that interact with specific protein transport machineries located in the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig 2).

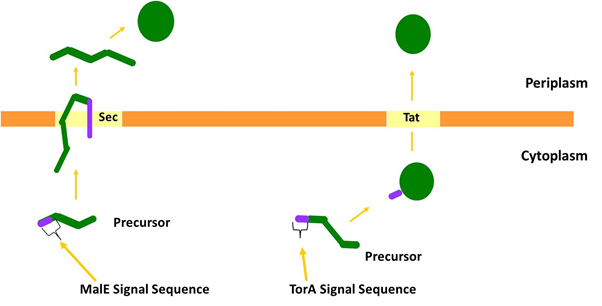

We considered two protein transport pathways for the transport of PP1, the Sec and Tat transport pathways. These pathways are very different because Sec transports unfolded proteins while Tat only transports folded proteins. We utilised both of these pathways because we did not know which transport route PP1 (which is a non-secreted human protein) would be compatible with.

Localisation of PP1 is mediated via different signal sequences

Specific sequences of amino acids called signal peptides target proteins to the Tat and Sec pathways. These signal peptides interact with the cognate transport machineries and are usually cleaved off at a late stage of transport by a periplasmically-located leader peptidase enzyme. Some signal peptides contain a special sequence called a ‘lipobox’, containing an invariant cysteine residue. These signal peptides are cleaved just before the conserved cysteine, and during this process the cysteine is fatty-acylated and the protein becomes anchored in the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane. The signal peptide cleavage and acylation reactions are carried out by a protein called lipoprotein signal peptidase (1).

In the B. subtilis chassis, we utilised the Sec pathway to export PP1. In order to achieve this we fused PP1 to the PrsA signal peptide. PrsA is a membrane-associated lipoprotein that is transported from the cytoplasm via the Sec pathway, and the ultimate aim was to anchor PP1 to the cell surface through this lipoprotein signal sequence.

We chose to target PP1 to the periplasm of E. coli by both the Sec and Tat protein transport systems. The periplasmic maltose-binding protein (MalE) is transported by the Sec machinery and we fused the signal sequence from this protein to PP1 to target it through Sec. Separately we targeted PP1 to the Tat machinery by fusing the signal sequence of TMAO Reductase (TorA), a well-characterised Tat substrate protein, to PP1.

Figure 2: The two major pathways by which proteins are transported across the cytoplasmic membrane. The Sec pathway transports proteins in an unfolded conformation; they are then folded at the opposite side of the membrane. Often Sec substrate proteins contain disulphide bonds that are inserted into the substrate during folding in the periplasm. The Tat pathway exports folded proteins. Many Tat substrates in E. coli, for example TorA, contain non-covalently bound metal cofactors that are inserted into the protein prior to export.

How was toximop made in the lab?

A pGEX6P plasmid encoding PP1 was kindly gifted to us by scientists in the Division of Signal Transduction Therapy at the University of Dundee.

To adhere to the iGEM rules and regulations, it was necessary to remove the specified illegal PstI restriction site present in PP1. The modified gene was then cloned into both pUniprom and pSB1C3 plasmids. In order to facilitate immunochemistry we chose to supply PP1 with an influenza virus hemagglutanin (HA) tag which can be detected with commercial antibodies. This tag was added to the C-terminus of PP1 and this modified PP1 is referred to as PP1-HA.

Signal sequences

TorAsp-PP1-HA: DNA encoding the TorA signal sequence (TorAsp) was obtained from the Division of Molecular Microbiology at the University of Dundee.

MalEsp-PP1-HA: DNA encoding the MalE signal sequence (MalEsp) was obtained by PCR using the chromosomal DNA of E. coli MG1655 as template.

PrsAss-PP1-HA: DNA encoding the PrsA signal sequence (PrsAss) was obtained by PCR using chromosomal DNA of B. Subtillis 3610 as template.

DNA encoding each of the signal sequences was cloned individually into the pUniprom vector. After the sequence of the inserts had been verified, DNA encoding PP1-HA was cloned downstream and in frame. Since the pUniprom plasmid can be expressed in E. coli MC4100 but not B. Subtillis, the resultant PrsAss-PP1-HA construct had to be re-cloned into the Bacillus vector pDR110. The aim was then to integrate the construct into the B. subtilis chromosome via recombination with the amyE locus.

Making the Mop

PP1 expression and targettingE. coli MC4100 cells express our engineered PP1 protein

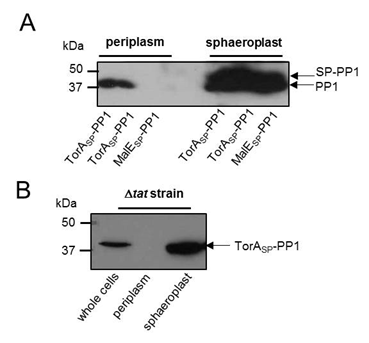

Firstly we wanted to confirm that our constructs were being expressed. Therefore E. coli MC4100 cells carrying plasmids producing PP1 fused to either TorAsp (TorASP-PP1) or MalEsp (MalESP-PP1) were fractionated by permeabilisation of the outer membrane and digestion of the cell wall. This generates a periplasmic fraction and a sphaeroplast fraction (which is the cytoplasm of E. coli bounded by the inner membrane). The periplasm and sphaeroplast samples were analysed by western blotting using an anti-PP1 antibody (Kindly gifted to us by Prof. Tricia Cohen of the Protein Phosphorylation and Ubiquitylation Unit at the University of Dundee). As shown in Fig 1A, PP1 was successfully produced in both TorASP-PP1 and MalESP-PP1 -cells.

TorASP-PP1 can be exported to the periplasm by the Tat pathway

Analysis of the periplasmic fractions from cells producing TorASP-PP1 and MalESP-PP1 clearly shows the presence of PP1 in the periplasmic fraction when supplied with a Tat targeting signal peptide but not a Sec-targeting signal peptide.

To confirm that the Tat pathway was definitely responsible for the transport of PP1 fused to the TorA signal peptide, a mutant of MC4100 lacking a functional Tat pathway (ΔtatABC) was used. ΔtatABC cells producing our TorASP-PP1 construct were fractionated and analysed by western blotting, as above, PP1 was present in whole cell and sphaeroplast fractions but absent in the periplasmic fraction. Thus, TorASP-PP1 is transported across the inner membrane by the Tat pathway.

Figure 3: PP1 can be exported to the periplasm by the Tat pathway. (A) E. coli MC4100 cells producing PP1 fused to the signal peptides of (i) TorA (TorASP-PP1; Tat-targeting) or MalE (MalESP-PP1; Sec-targeting) or (B) E. coli strain MC4100 ΔtatABC (which lacks a functional Tat pathway) producing TorASP-PP1 were cultured in LB medium, cells harvested, washed and the periplasmic and sphaeroplast fractions prepared. Samples were separated by SDS PAGE (15% acrylamide), transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with anti-PP1 antibody. All the samples represent the same proportion of total protein present in the two fractions.

References

- Palmer, T. and Berks, B.C. (2012) “The twin-arginine translocation (Tat) protein export pathway”. Nature Reviews Microbiology 10, 483-4

</div>

</div>

</div>

<script src="http://code.jquery.com/jquery-latest.js"></script> <script src="http://www.kyleharrison.co.uk/igem/js/bootstrap.min.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

"

"