Team:Groningen/Safety

From 2013.igem.org

Safety forms were approved on September 29, 2013 by the iGEM Safety Committee

Safety

On this page the safety related ethics and issues are discussed.

First with a general introduction and eventually the specific related safety of our project.

First with a general introduction and eventually the specific related safety of our project.

Introduction

In 1983 the World Health Organization (WHO) published the first edition of the laboratory biosafety manual. This manual was composed for countries over the world to accept and implement the concepts of biological safety. This gave countries a scaffold to develop their national regulations in handeling pathogenic microorganisms.

The revised version of this manual in 2004, also addresses the current biosafety issues we are facing today, e.g. the use of genetic modified organisms (GMOs) [1]. Also a more recent development is the upcoming field of synthetic biology, which brings along more biosafety and ethical issues (discussed below).

In here, we will address the biological safety issues directly on our project with detailed information described by various organisations such as the WHO and the Commission on Genetic Modification (COGEM).

Infective microorganisms are classified, for laboratory work, by four risk groups. In this iGEM project we are working with Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. For E. coli it is known that it can cause irritation to skin, eyes, and respiratory tract, and could affect kidneys, however this is a low individual and community risk [2]. B. subtilis is unlikey to cause any harm to individual and community, and is also Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) [3].

In this case, the only relevant risk group for our project is Risk Group 1 (no or low individual and community risk). Microorganisms classified in this group are unlikely to cause human or animal diseases are classified in this group. For Risk Group 1 a Basic Biosafety Level 1 (BSL1) laboratory is required.

For our project we work on a BSL1 lab and all persons that do laboratory related work have a Good Microbiological Techniques (GMT) certificate. With this certificate we are approved to work with Risk Group 2 organisms in a BSL2 laboratory according to the advice of the Royal Dutch Society of Microbiology.

|

|

Figure 1: An example of a BSL1 laboratory. |

Synthetic Biology

The synthetic biology is an emerging discipline in biology with possible great potential, however it brings along new biosafety and ethical questions [4]. Nowadays, the risk assessment framework is still applicable of the developments in synthetic biology, however, eventually when new developments in synthetic biology will arise the current risk assessments will not be adequate anymore [5].

The International Risk Governance Council (IRSC) stated risks that arose from reports of various organisations [4]:

Insufficient basic knowledge about the potential risks posed by designed and synthetic organisms.

Uncontrolled release of novel genetically modified organisms with potential environmental or human health implications, either arising from accidental release into the environment or from applications entailing deliberate release.

Bio-terrorism, biological warfare and the construction of novel organisms designed to be hostile to human interests.

The possible emergence of a ‘bio-hacker’ culture in which lone individuals develop dangerous organisms much as they currently create computer viruses.

Patenting and the creation of monopolies, inhibiting basic research and restricting product development to large companies.

Many of those safety and ethical questions have been discussed in Schmidt, M. 2009 [6].

Our Project: The Coating GEMs

Safety Precautions on the lab

DNA stain

Ethidium Bromide (EB) is a fluorescent nucleic acid stain that is commonly used in agarose gel electrophoresis. However, EB is a hazardous chemical in case of ingestion, skin contact (irritant), eye contact (irritant), and inhalation [7]. It was observed that EB concentrations of 0.1-5µg/ml inhibit cell growth and the mitochondrial DNA synthesis of cultured L and BHK cells. EB treatment to these cell lines showed a structural alternation of covalently closed mitochondrial DNA. Also an increased degree of supercoiling and breakage of circular DNA was observed. These changes occurred in the pre-existing as in the newly synthesized DNA. The caused changes in the DNA by EB were reversible by growth of cells in EB-free medium [8].

On the carcinogenic effects of EB no data is available, however it is highly plausible that, because of its interaction with DNA, it may cause mutations and may lead to carcinogen effects.

Therefore, we choose to use SERVA DNA Stain G. This stain is non-carcinogenic and according to the AMES test it causes significantly fewer mutations than EB according to SERVA (see safety test results).

Safety Aspects of Our Project

In our projected we created a Coating Genetically Engineered Machine.

The machine is an engineered B. subtilis strain that can swim to the heated implant and secrete silk. We visualized our idea in the movie shown below.

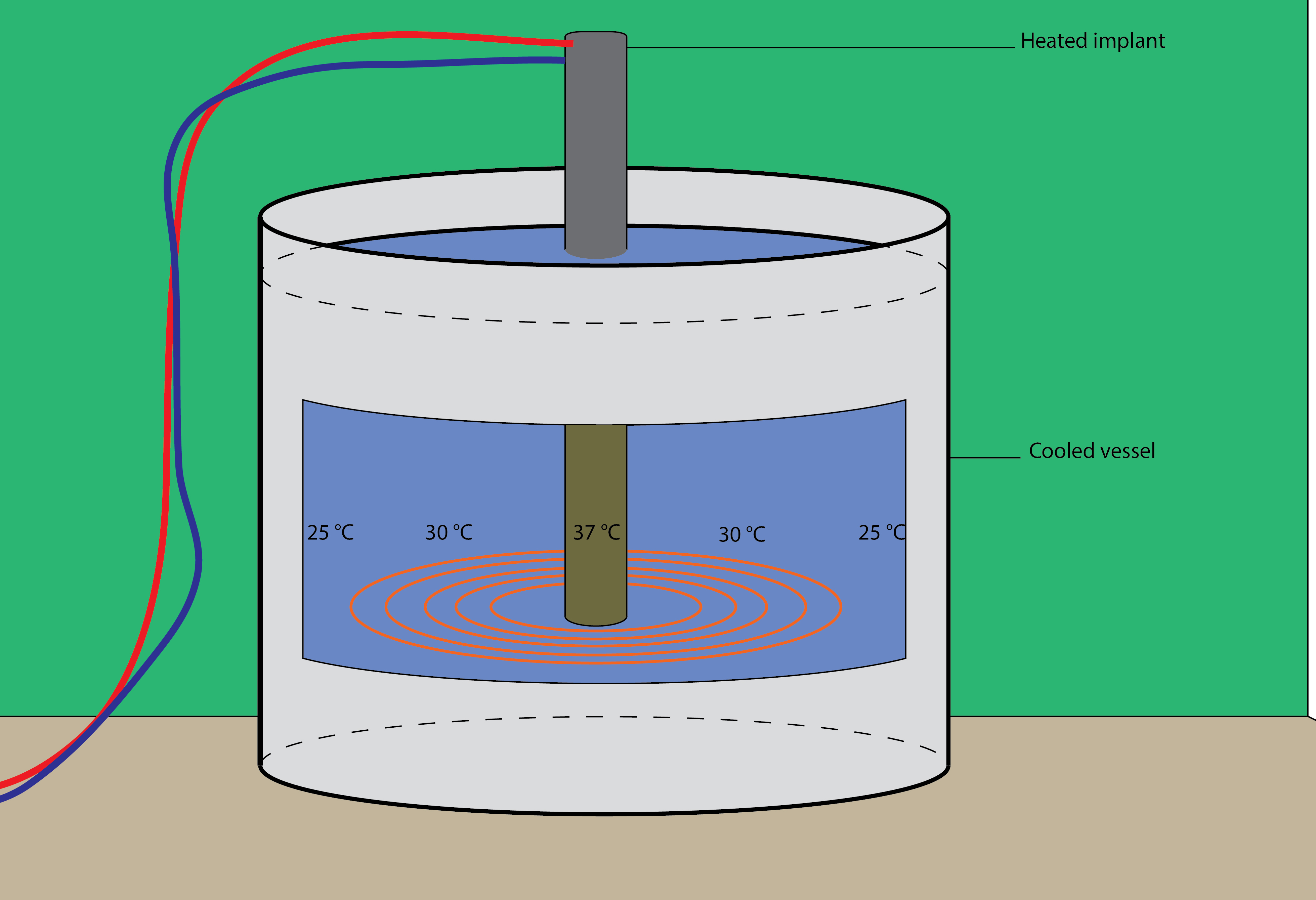

The coating of the implant will be performed in vitro in a laboratory and can be scaled up to industrial levels easily. A possible setup is shown in Figure 1.

| The Coating GEMs | Possible Experimental Setup: |

|---|---|

|

Figure 2: A possible setup of our project |

The coating GEM its swimming behavior is adapted by linking circuits of genes in another way. Thus, at that point no new genes are introduced. However to introduce the new gene circuit we use a standard laboratory technique involving resistance genes that normally not occur in B. subtilis.

The silk protein gene (masp2) originating from Argiope Aurantia is an eukaryotic gene that is codon optimized for B. subtilis.

To make sure we have the first layer of our silk on our implant, the silk has an Strep-Tag that can bind to the streptavidin coated implant. Implants are widely used and will not be discussed in the risk assessments, however streptavidin, that is coated on the implant, is a non human protein and will be discussed in 3.1.1.

Our project is designed for use that is inside a laboratory, however accidents can occur and can cause release from our 'Coating GEM' into the community and environment. These possible risks are discussed in 3.1.2.

Risk Assessments

Streptavidin coated implant

The implant we coat in vitro under laboratory condition has streptavidin coated covalently to its surface. The implants can be sterilized, after the coating procedure, so all bacteria will be removed after this sterillisation process. However the implant is still coated with streptavidin and this could raise questions for the risk assessment.

In Xu & Screaton 2002 a in vivo visualization method of tumor cells is described involving stretavidin marked tumor cells [9]. This shows that streptavidin can be used in the body and this indicates that no complications will occur.

Release in Community & Enviroment

B. subtilis is a GRAS[3], non-pathogenic, gram positive bacterium and is commonly found in soil. A accidental release of the 'Coating GEM' would not give any risks to to the environment or human health. However due the short time-span of the iGEM competition we used 'standard' cloning techniques involving antibiotic resistance. So our 'Coating GEM' still contains an antibiotic resistance however, at the end of our project we want to use an antibiotic-free cloning technique described below.

A novel genetic manipulation technique, free of selection markers.

The authors of Zhang et al. 2006 [10] created a novel antibiotic-free cloning approach for B. subtilis. An E. coli toxin gene called mazF was used as counter selectable marker. MazF (mazF) is an endoribonuclease that specifically cleaves free mRNAs at ACA sequences and inhibits cell growth.

The mazF gene was placed under an IPTG inducible promoter in a cassette containing spectinomycin resistance gene and two directly-repeated (DR) sequences. When the cassette was transformed to B. subtilis by double crossover homologue recombination, it resulted in a IPTG sensitive strain. The right strain, selected for spectinomycin resistance, was cultivated for 24h in an antibiotic-free medium and sequentially plated on LB plates containing 1mM IPTG. This resulted in a single cross-over between the DR sequences, excising the mazF-cassete. An overview is shown in figure 3 below.

|

Figure 3: Image adapted from Zhang et al. 2006 [10]. Antibiotic-free cloning technique we want to use. |

References

[1] Laboratory biosafety manual 3rd revision, WHO[2] Website from American Biological Safety Association (ABSA): www.absa.org/riskgroups/bacteriasearch.php?genus=&species=coli

[3] Singh, M et al. Microbial Cell Factories 2009, 8:38

[4] Policy Brief: Guidelines for the Appropriate Risk Governance of Synthetic Biology from the International Risk Governance Council (IRGC) 2010

[5] Synthetic Biology – Update 2013: Anticipating developments in synthetic biology, COGEM Topic Report, CGM/130117-01

[6] Schmidt, M. Systems and Synthetic Biology 3, 1-4, Special Issue: Societal Aspects of Synthetic Biology

[7] Material Safety Data Sheet: Ethidium Bromide

[8] Margit M.K. Nass, Differential effects of ethidium bromide on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA synthesis in vivo in cultured mammalian cells, Experimental Cell

Research, Volume 72, Issue 1, May 1972, Pages 211-222, ISSN 0014-4827

[9] Xiao-Ning Xu, Gavin R Screaton, MHC/peptide tetramer-based studies of T cell function, Journal of Immunological Methods,

Volume 268, Issue 1, 1 October 2002, Pages 21-28, ISSN 0022-1759.

[10] Zhang, X. Z., Yan, X., Cui, Z. L., Hong, Q., & Li, S. P. (2006). mazF, a novel counter-selectable marker for unmarked chromosomal manipulation in Bacillus subtilis.

Nucleic acids research, 34(9), e71-e71.

"

"