Team:Minnesota/Project/Pichia Expression System

From 2013.igem.org

Template:Minnesota Main Styles2

Engineering Caffeine Biosynthesis in Baker’s Yeast

The second project explored during the summer was the cloning of genes from Coffea canephora into Saccharomyces cerevisiae to facilitate caffeine biosynthesis in yeast. Caffeine is the one of the most widely consumed substances in many areas of the U.S. but despite this, many problems exist with the current caffeine production system, such as the plant-based production, which is not only dependent on climate and nutrients but is susceptible to disease and pests; the extraction process which is slow and relatively costly; relatively limited modes of consumption—coffee (bitter and a potential allergen) and energy/ soft drinks (linked to tooth decay, high body weight and Type II Diabetes). Yeast is an ideal organism in which to produce caffeine for a number of reasons. Yeast is used in food products and consumed regularly. It is non-pathogenic and is a model organism preferred in industry use. Working with S. cerevisiae is also a great way to contribute parts to the registry, as parts are lacking for yeast. Providing caffeine biosynthesis genes to the registry will allow future teams to explore and compare this well-characterized caffeine biosynthetic pathway to less characterized pathways (i.e. caffeine biosynthesis in Mate). Additionally, these genes allow for comparison of biosynthesis of other alkaloids in yeast, which is an area that is not yet well studied. In addition to caffeine biosynthesis genes, a yeast-E. coli shuttle vector was also designed and pieced together via Gibson Assembly for use by future iGEM participants. Previously submitted shuttle vectors use auxotrophic markers for selection in yeast, which results in two potential weaknesses: rich media cannot be used, which can hinders yeast biosynthetic capacity, and cell death can cause nutrients from dying cells to diffuse into media, creating the potential for false positives. The use of an antibiotic resistance marker (specifically G418-resistance) as the selectable marker for yeast in our shuttle vector overcomes these two weaknesses. With the help of the parts we’ve developed, a caffeine-producing yeast strain could be used to add caffeine to fermented foods and beverages, such as bread. Don’t have time for that cup of coffee? Have caffeinated toast instead!

Goal

To achieve exogenous production of caffeine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and to create tools to ease the process of introducing protein expression pathways in yeast for future research.

Background

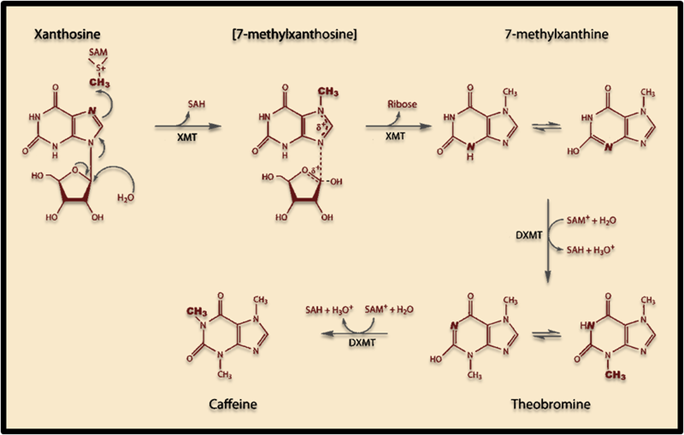

Caffeine synthesis in most caffeine producing plants requires three enzymes to convert Xanthosine to the final product: Monomethylxanthine methyltransferase (MXMT1), 7-methylxanthosine synthase (XMT1), and 3,7-dimethylxanthine N-methyltransferase (DXMT1). Both the XMT1 and DXMT1 genes produce bifunctional enzymes and this particular pathway was chosen so that one less enzyme would be required in the synthesis (compared to three in Coffea Arabica)

The induction of this novel pathway in S. cerevisiae requires two additional enzymes from C. canephora: XMT1 and DXMT1. S. cerevisiae will produce the required metabolic precursors to Xanthosine, where after the XMT1 enzyme from C. canephora will use the substrate to synthesize 7-methylxanthosine, then 7-Methylxanthine. DXMT1 will then convert it to Theobromine and finally caffeine.

Figure 1. Scheme showing proposed caffeine biosynthetic pathway in S. cerevisiae.

Methods

After settling on the two genes, the sequences were taken from NCBI and finalized for synthetic synthesis (XMT1 accession number DQ422954 and DXMT1 accession number DQ422955). A program was designed to optimize these plant genes for yeast use. Because of the similarity of the two genes (~88% similarity) the program was also designed to identify regions of homology between the two genes and adjust the codon usage such that homologous recombination will not occur at the nucleotide level while the overall protein sequence would be retained. The codons were chosen in descending order of complementary tRNA abundance. Any BioBrick cut sites found within the gene sequences were also removed.

To synthesize the overall plasmid backbone, PCR primers were designed to amplify five desired fragments (with 25-30 bp overlap) from different plasmids, which could be joined by Gibson Assembly:

1. BioBrick destination plasmid pSB1C3 containing the MCS and rep (pMB1).

2. BioBrick destination plasmid pSB1C3 containing the Chloramphenical resistance gene.

3. 2u Gibson Extract provided by the Schmidt-Dannert lab (University of Minnesota) containing the 2u ORI for yeast.

4. pkT127 provided by the Schmidt-Dannert lab containing G418 resistance genes and tTEF1.

5. ATCC plasmid provided by the Schmidt-Dannert lab containing the ADH1 promoter to drive the G418 R gene.

Parts List

BBa_K814000 dehydroquinate synthase (DHQS) generator

BBa_K814001 ATP-grasp (ATPG) generator

BBa_K814002 dehydroquinate O-methyltrasferase (O-MT) generator

BBa_K814003 shinorine non-ribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) generator

BBa_K814004 mycosporine-glycine biosynthetic pathway

BBa_K814005 shinorine biosynthetic pathway

BBa_K814006 negative control for mycosporine-like amino acid biosynthesis

BBa_K814007 ScyA (acetolactate synthase) generator

BBa_K814008 ScyB (leucine dehydrogenase) generator

BBa_K814009 ScyC generator

BBa_K814010 partial scytonemin biosynthetic pathway, scyCB

BBa_K814011 scytonemin biosynthetic pathway, scyBAC

BBa_K814012 XMT1 protein generator

BBa_K814013 DXMT1 protein generator

Figure 2: Pieces for Gibson assembly of our novel, shuttle backbone. The individual pieces relate to the described components enumerated above. 1. Purple arrow; 2. Orange arrow; 3. Green arrow; 4. Blue arrow; 5. Light green arrow.

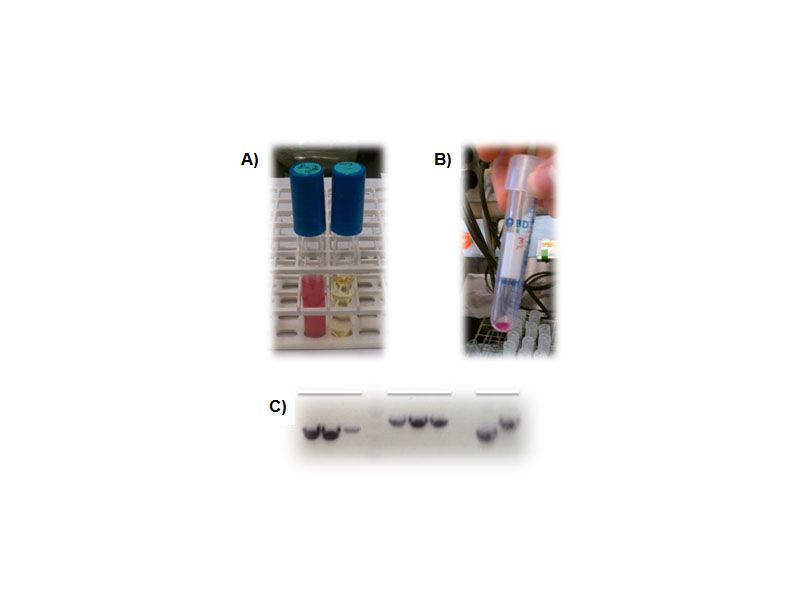

Figure 3. Creation of a shuttle vector designed for BioBrick components. A), Overnight culture of the pSB1C3 shipping vector showing RFP expression (a blank LB tube is shown as a control on the right). B), RFP expression in the pGHMM2012 shuttle vector. Cell pellets clearly indicate expression of RFP from this plasmid. C), PCR screening for caffeine biosynthetic components into pGHMM2012. The panels from left to right are positive clones for Xmt, Dxmt and controls for each of these components.

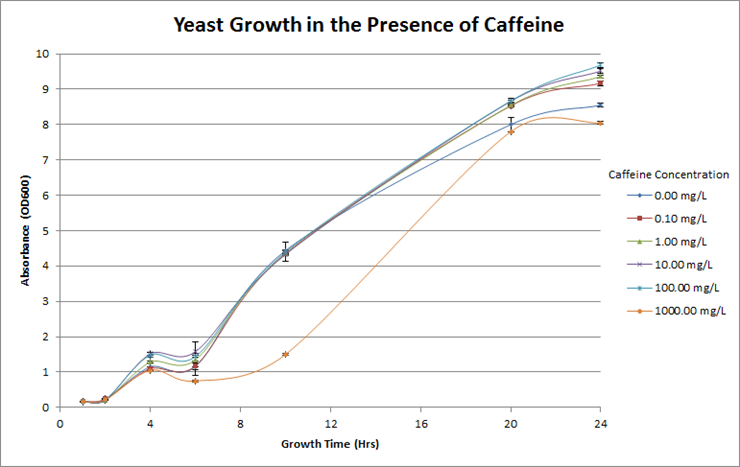

Figure 4. Investigation of caffeine toxicity in yeast. The yeast were resilient in the presence of caffeine and there was no significant decrease in growth overtime at each different concentration. For reference, the concentration of caffeine in coffee is roughly 600mg/L.

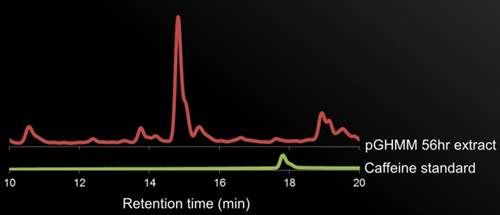

Figure 5. HPLC Data. description.

Conclusions

We were able to design and synthesize a novel yeast- E. coli hybrid plasmid which was optimized to prevent homologous recombination in our two synthetic genes: XMT1 and DXMT1.

If the HPLC results can confirm the presence of caffeine in the yeast cultures, we would confirm the presence of the two target proteins by SDS-PAGE, possibly even performing antibody detection if there is difficulty confirming the presence.

If the HPLC results cannot confirm the presence of caffeine, the first step would be to sequence our genes and align them with the sequences submitted to IDT for the gBlocks. We could also measure the production of the intermediates compared to the cultures to test whether caffeine synthesis is being arrested in the pathway.

Click here to return to Projects page.

"

"