Team:UCLA/Project/ProjectDesign

Contents |

Project Design

Inspired by the natural Bordetella phage's diversity-generating retroelement (DGR) system, we sought to develop an in vitro analog that could produce even greater numbers of possible major tropism determinant (Mtd) protein variants. This would test the structural limits of the Mtd and its target-binding ability, provide a broader perspective on the bacteriophage’s host-range specificity, and potentially introduce a new method of generating antibody-like proteins that can bind onto selected targets.

Generating Diversity

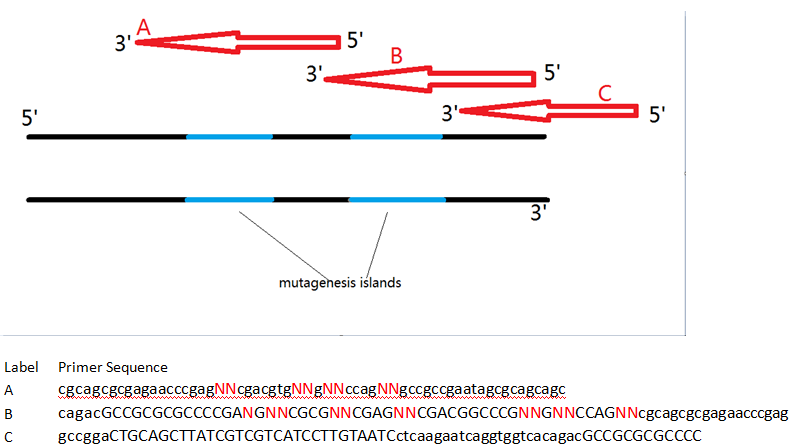

To this end, we first isolated the Major tropism determinant (mtd) gene from the Bordetella phage genome, which was generously donated to us by Jeff Miller’s lab at UCLA. Initial attempts at moving the components of the DGR into E. coli have not successfully yielded a functional product. However, the Mtd protein is still a choice candidate for our project given its ability to resist structural deformation following mutagenesis of the variable binding domain. Without the native reverse transcriptase-mediated homologous recombination system to generate diversity, we designed a series of overlapping oligonucleotides with mutagenic islands that bind to the mtd gene’s variable repeat and introduce random nucleotides during PCR. The farthest oligonucleotide at the 3’ end of the gene also contains a Serine-Glycine linker and a FLAG-tag that would facilitate purification from undesirable byproducts during mRNA display.

This in vitro system has several advantages over the natural DGR, and boasts even greater possible protein diversity. Naturally, only adenine bases within the mtd gene’s variable repeat region are modifiable. While this still provides a significantly large number of possible variants, the primers used in our experiments do not have to follow the same adenine site-specific mutation restrictions, and permit entire sections to be modified. Primer-mediated mutagenesis thus provides even greater sequence variation than the normal DGR system. An enormous library of unique variants can increase the chances of identifying a protein-binding species in a screen. Having a large copy number of each variant is also important, as this number invariably decreases during purification steps – too few, and an actual protein-binding variant might be lost even before the final screening step!

There are few cost-efficient methods of calculating the number of copies per mtd variant within a given sample. However, the maximum average copy number per variant within a given sample can be calculated assuming that every possible variant is present at least once before copies of the variants are formed. This maximum is only useful as a loose reference since it is unrealistic to assume that the obtained sample contains at least one of every possible variant. Our protocol involves two separate PCR setups, the second of which uses only a subset of the variants generated from the first. This step limits the sequence variation at the first mutagenic island in the variants present in the final assembled library.

Displaying Diversity

At this time of writing, we have been unable to complete mRNA display and screening of the Mtd library. However, we will discuss the steps we have taken and are still optimizing, as well as future directions. We encourage you to stay tuned for the final results which will be posted here!

mRNA display links each protein variant within our library to its corresponding coding sequence. This allows for identification of successful protein-binding variants following screening. The technique has been widely used throughout the literature for similar screening and protein selection applications. Our mRNA display protocol can be completed in two days once optimized, and like other published protocols, is done entirely in vitro.

As previously mentioned, it is important to monitor and take steps to reduce the loss of sample diversity through the purification steps. A measure of the sample’s OD can be taken after purification steps to track any losses. Following purification of the in vitro transcription products, the sample should be ligated to the puromycin-linker. Maintaining near-equimolar amounts of RNA, splint (the oligonucleotide which connects the RNA to the puromycin-linker), and puromycin-linker has given us optimal results. RNA tertiary structures can reduce efficiency in these processes and should be avoided. Heating samples at 65 degrees Celsius for a few minutes can help prevent this from occurring. Prior to ligation, it is important to heat the RNA sample in the absence of DNA ligation buffer or ligase since these reagents often include magnesium ions, which may facilitate formation of tertiary structures. Following ligation, RNA samples should be run on a gel by electrophoresis to separate the fully ligated RNA-splint-linker species from the smaller splint and linker fragments. The size difference between the unligated and ligated RNA may be too small to resolve separately on a gel. However, they can be isolated by using oligo-dT columns. The splint and linker provide the ligated RNA with a poly-A tail which can bind onto the column.

The sample can then be translated in vitro using commercial kits. It is important to translate the RNA after purifying the sample through oligo-dT columns, since keeping unligated RNA will reduce translation efficiency. High salt concentrations used during oligo-dT column purification could also disrupt the conjugated proteins. The protein-RNA samples can then be separated from untranslated RNA by pulling down the translated FLAG tag using antibodies or affinity columns. Finally, purified protein-RNA samples can be reverse transcribed into protein-DNA samples. While converting RNA to DNA earlier may decrease the chance of allowing RNase or harsh experimental conditions to degrade RNA, the order described provides the greatest efficiency of reverse transcription by removing competing incomplete samples. Steps following translation should all be done with as few freeze/thaw cycles in between. Completing the remaining procedures in one shot is preferred.

Screening the sample

We plan on using the final protein-DNA library to screen for Mtd variants that can bind to proteins expressed on the surface of E. coli. If successful, our results would highlight the remarkable structural properties of the Mtd, and provide evidence that the DiversiPhage system could potentially be used to generate antibody-like proteins that can bind to specified targets. We are not immediately concerned about what protein the Mtd will specifically bind to, since binding to any surface protein on E. coli will demonstrate a change in specificity from its natural target. As a negative control, we will use the wild-type Mtd in the same screen against E. coli. 3D images of Mtd-target interactions suggest that the Mtd forms into a trimer through interactions at the static scaffold region. The mutagenic islands only modify the variable binding region. Since it is possible that each of the three associated monomers has a unique variable region, the possible permutations of complexes may enable binding to an even greater range of targets.

It is important to mention that the screening methods will vary depending on the nature of the desired target – a different setup can be used to screen for binding against free-floating proteins than proteins fixed to a surface. A pre-clear (negative selection) step may be necessary if a pre-specified target will be bound to beads or a defined matrix. For example, if beads are to be loaded with the desired target, the sample should first be run through the beads alone as a control. The flow-through can then be collected and used in the final screen. There are multiple approaches we can take to test binding of our library to E. coli and determine which screening method is most efficient. These include applying our sample over a lawn of E. coli, into a liquid culture solution, or to a target-immobilized bound to a scaffold

Alberts, B., et al. "The Generation of Antibody Diversity." ''Molecular Biology of the Cell.'' New York: Garland Science, 2002. Print.

Dai, W., et al. "Three-dimensional structure of tropism-switching Bordetella bacteriophage." PNAS. 107.9 (2010):4347-52. Print.

Guo, H., et al. "Target Site Recognition by a Diversity-Generating Retroelement." PLoS Genetics. 7.12 (2011). Web.

Lipovsek. D., A. Pluckthun. "In vitro protein evolution by ribosome display and mRNA display." Journal of Immunological Methods. 290 (2004):51–67. Print.

Liu, R., et al. "Optimized synthesis of RNA-protein fusions for in vitro protein selection". Meth Enzymol. 318 (2000):268–93. Print.

Liu, M., et al. "Reverse Transcriptase-Mediated Tropism Switching in Bordetella Bacteriophage." Science. 295.5562 (2002): 2091-4. Print.

Medhekar, B., J. Miller. "Diversity-Generating Retroelements." Curr Opin Microbiol. 10.4 (2007):388-95. Print.

Roberts, R.W., J.W. Szostak. "RNA-peptide fusions for the in vitro selection of peptides and proteins." Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94.23 (1997):12297-302. Print

Smith, G., V. Petrenko. "Phage Display." Chem. Rev. 97 (1997):391-410. Print.

"Podoviridae." ViralZone. ExPASy, n.d. Web. 2013.

Yuan, T.Z., et al. "Protein Engineering with Biosynthesized Libraries from Bordetella bronchiseptica Bacteriophage." PLoS ONE. 8.2 (2013). Web.

"

"