Header

Contents |

Overview :

We decided to use nanoparticles as our carrier. We then had to find which kind of nanoparticles would suit our project the best. We first thought about polymers, but we needed something that could easily be degraded. So, we decided to use gelatin, which can be specifically degraded by enzymes. What's more, we found that many different kinds of gelatin nanoparticles had been made, with various loadings, such as proteins, organic molecules or DNA. We made our gelatin nanoparticles using a modified two-step desolvation method, and loaded them with fluorescently labeled dextran and recombinant GFP. We also labeled the nanoparticles directly with a dye. In addition, all of them were biotinylated, so that they could be linked to bacteria expressing streptavidin on their surface.

Making nanoparticles :

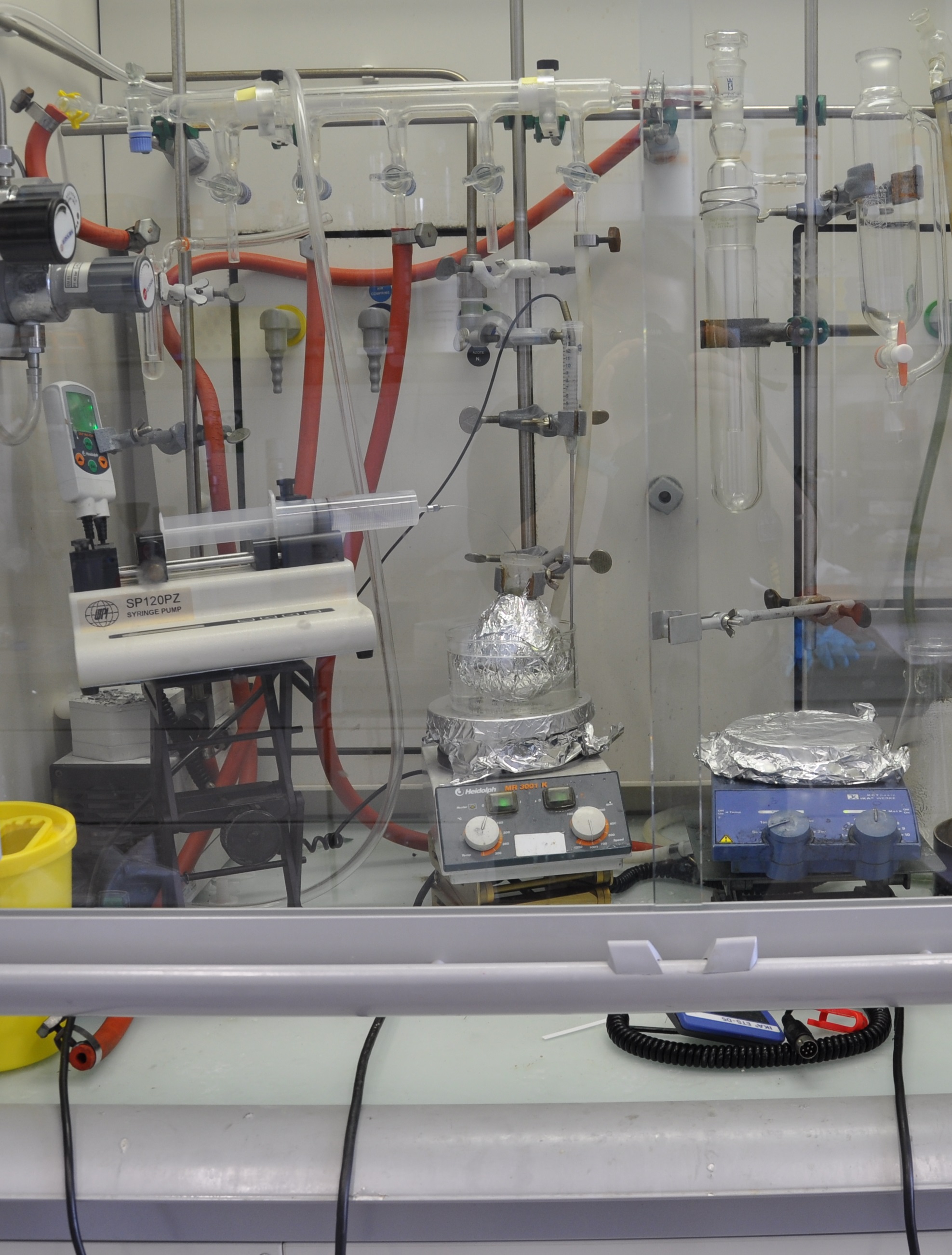

We made our gelatin nanoparticles using a modified two-step desolvation method [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19534472 [1]]. In this method, acetone is progressively added to a gelatin solution under constant stirring. Since gelatin is not soluble in acetone, two phases start to form: the acetone-water solution (organic) and the aqueous gelatin (non organic). In order to minimize the system's energy, the gelatin struggles to reduce its surface over volume ratio, hence forming nanospheres. At the end of the reaction, the nanoparticles are stabilized by glutaraldehyde crosslinking.

Before we found this protocol, we tried making similar nanoparticles using a protocol from another paper [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16849014 [2]]. However, the results weren't conclusive.

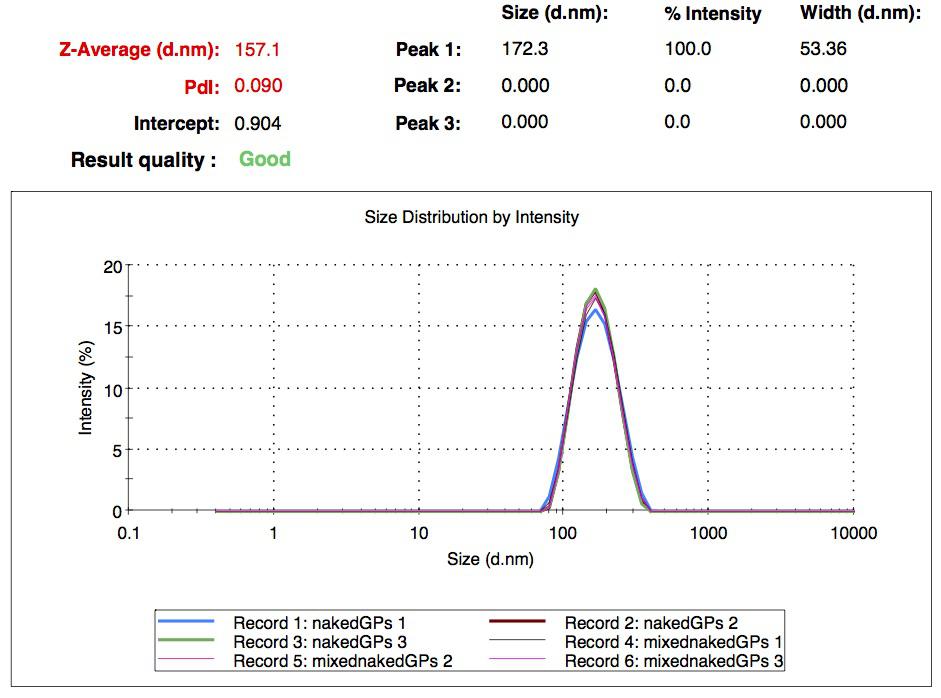

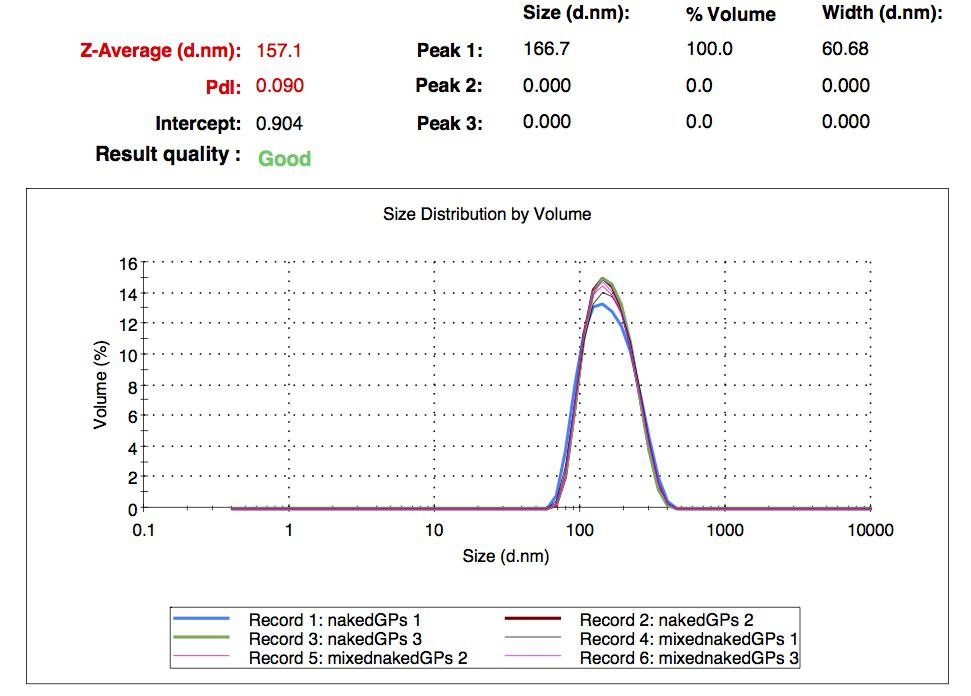

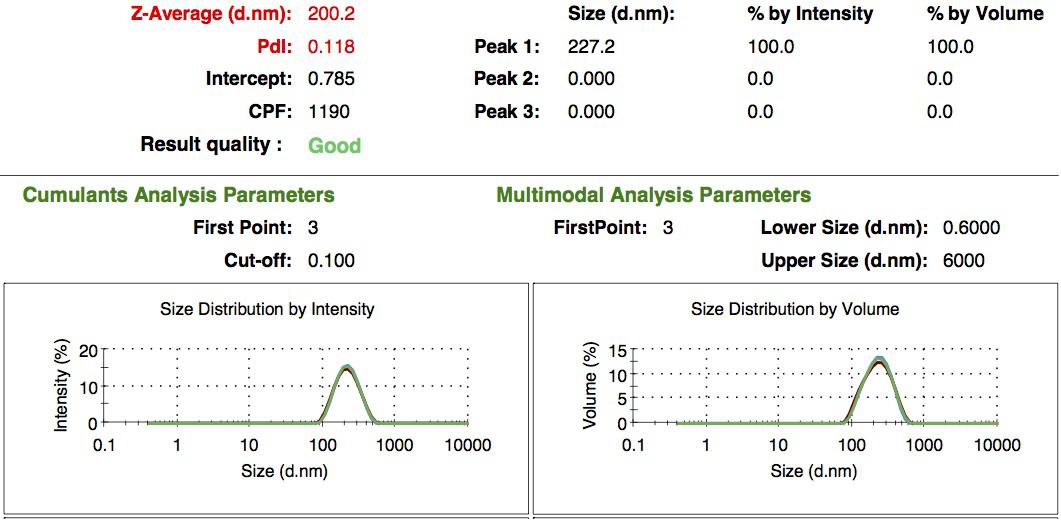

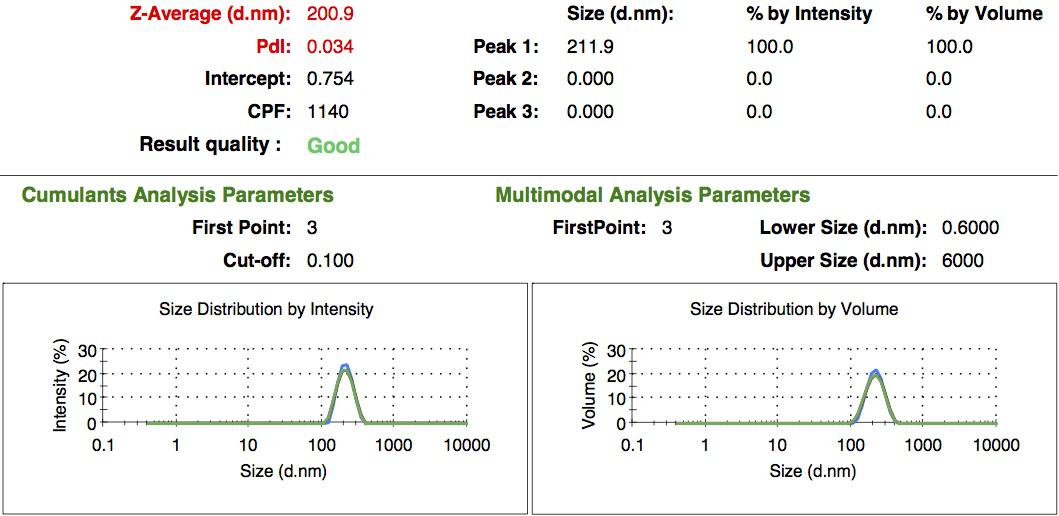

We characterized the nanoparticles using dynamic light scattering (DLS). This technique allows the determination of the size distribution profile of small particles in suspension. Indeed, small particles scatter light in all direction (Rayleigh scattering), but also undergo brownian motion. Hence, the intensity of the scattered light as a function of time is representative of the size of the particles. The first particles we made with this protocol have an average diameter of about 200 nm.

Biotinylating nanoparticles :

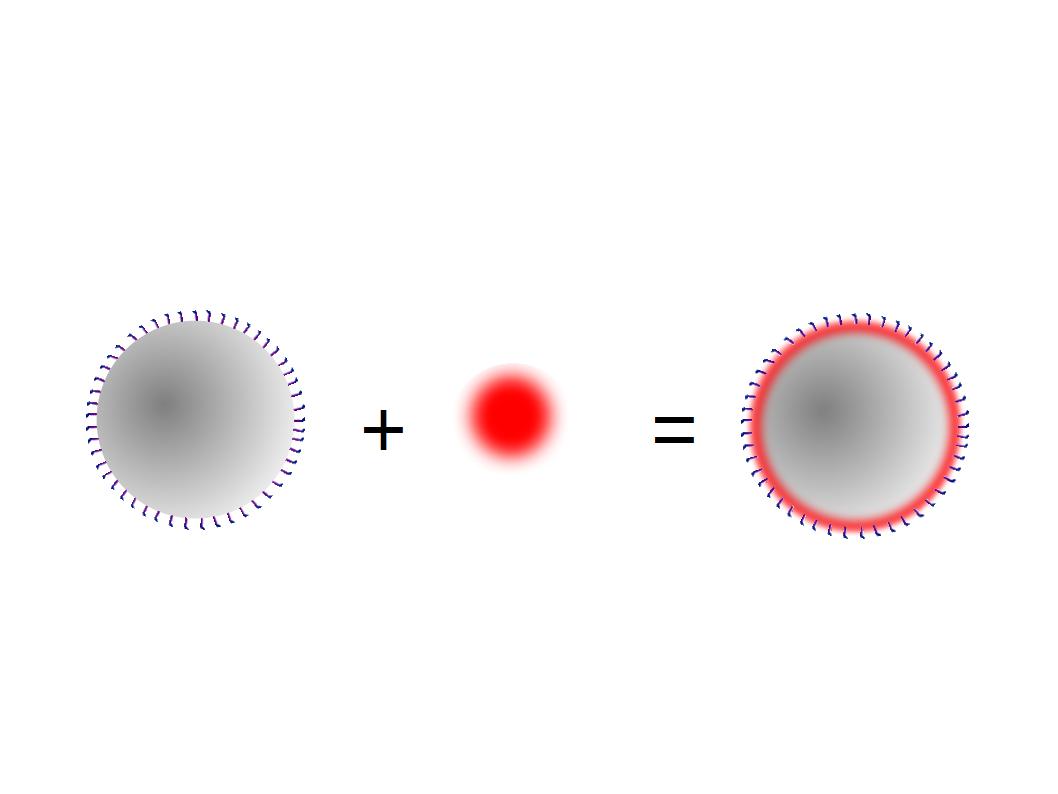

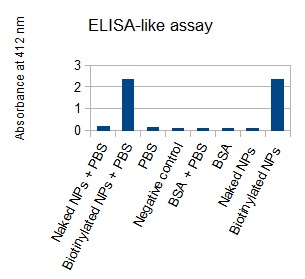

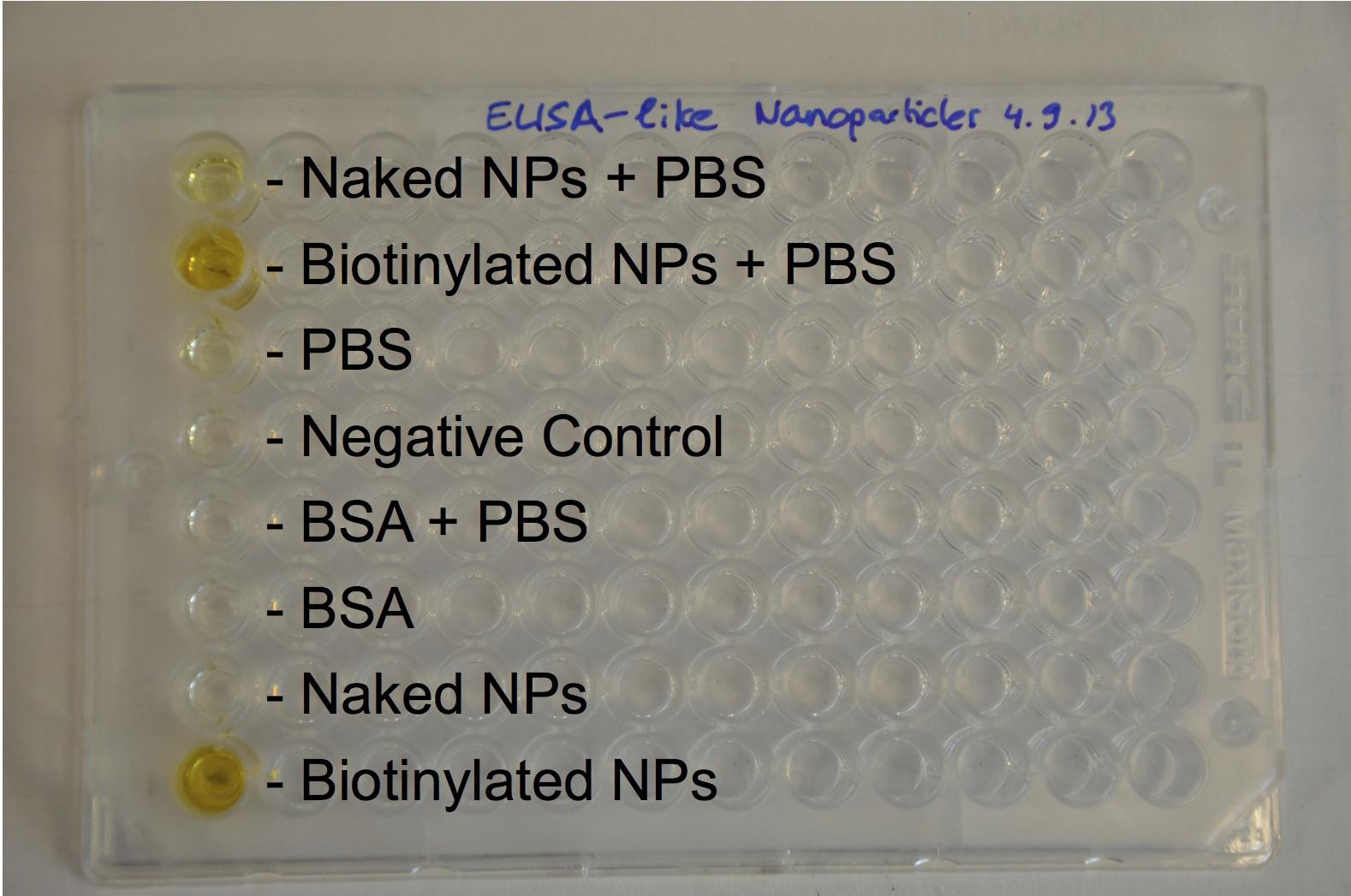

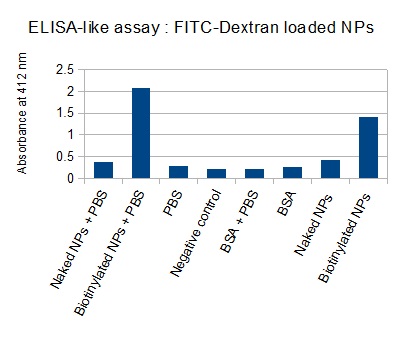

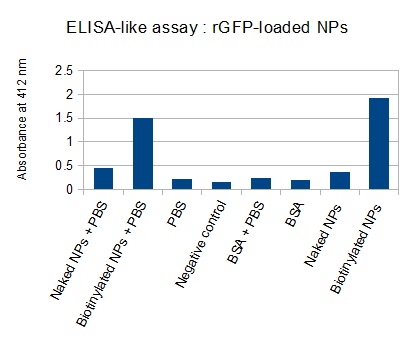

The next step was to biotinylate our nanoparticles. Biotin is a very small vitamin (244 Da) that binds very strongly to avidin and streptavidin proteins (Kd = 10 -15 M). Biotinylation was made using activated biotin (Sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-Biotin), which binds primary amino groups (-NH2) and forms stable amide bonds. We used an ELISA-like assay to assess the biotinylation. It showed that biotin was indeed present on the nanoparticles. Classical Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) allows detection of an antigen using a correspondent biotinylated antibody, which in turn is detected by avidin-HRP. Since we wanted to detect biotin directly , we skipped the first part of the assay (i.e. we started directly by adding avidin-HRP). We detected HRP activity using TMB ELISA Substrate, yielding a blue color where HRP, hence biotin, has been detected. Upon addition of ELISA stop solution (2N H2SO4), the positive samples turned yellow. Quantitative data can be obtained by measuring absorbance at 412 nm with a plate reader.

Labeling the nanoparticles :

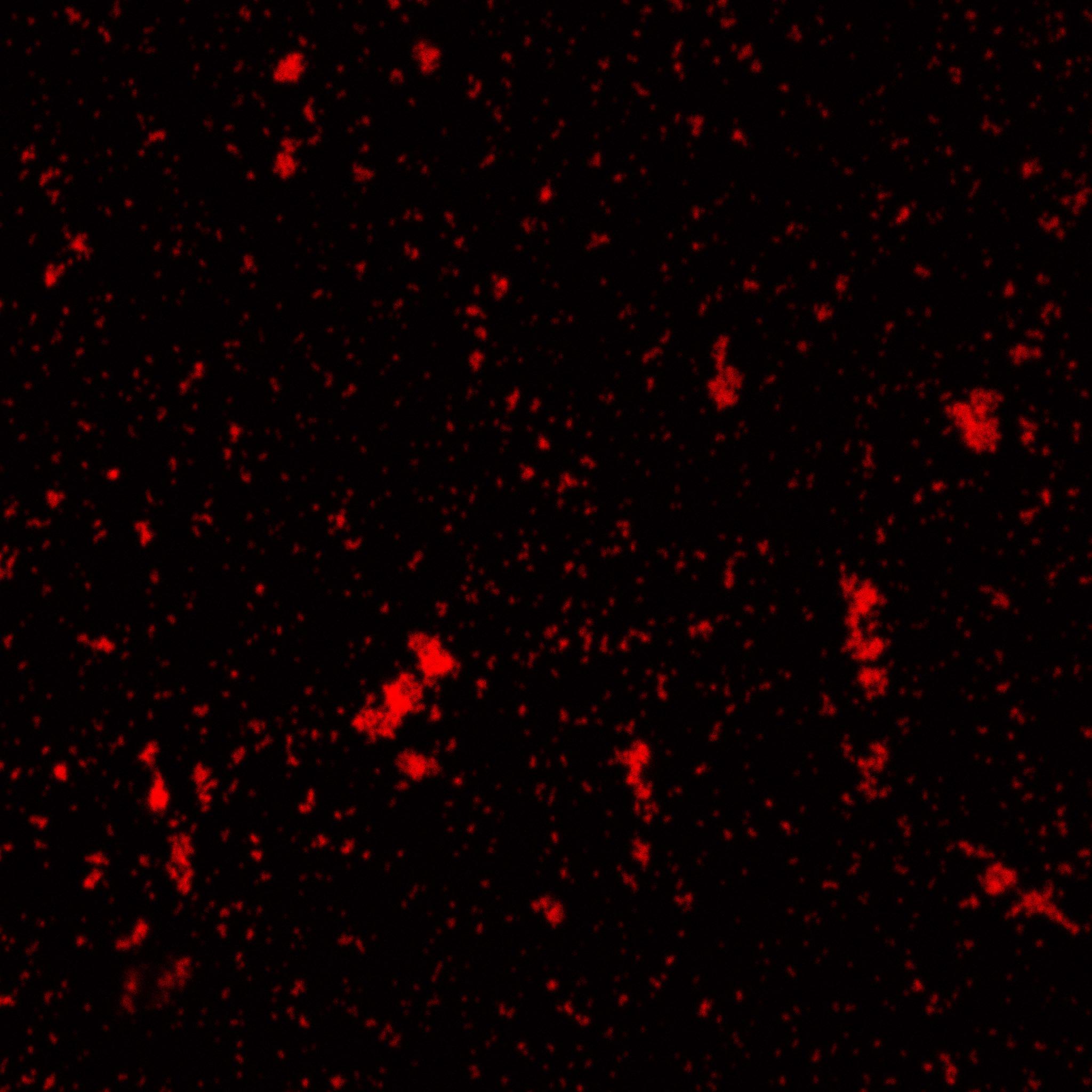

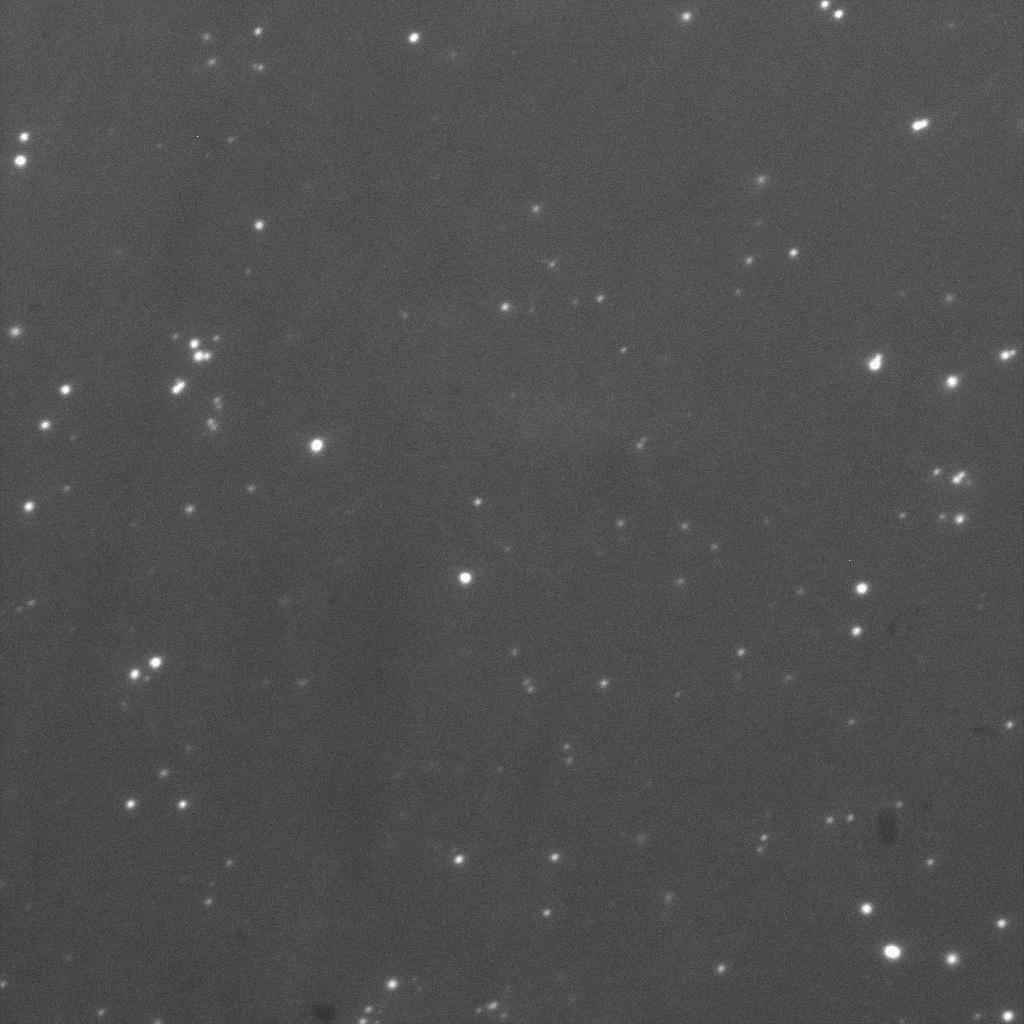

The biotinylated gelatin nanoparticles were labeled with an NHS-ester dye. This allowed visualization of the nanoparticles with a confocal microscope.

We can see that the nanoparticles were successfully labeled. However, there were many clusters. Hence, a second image was taken (using a fluorescent microscope) after sonication which separated the nanoparticles from each other.

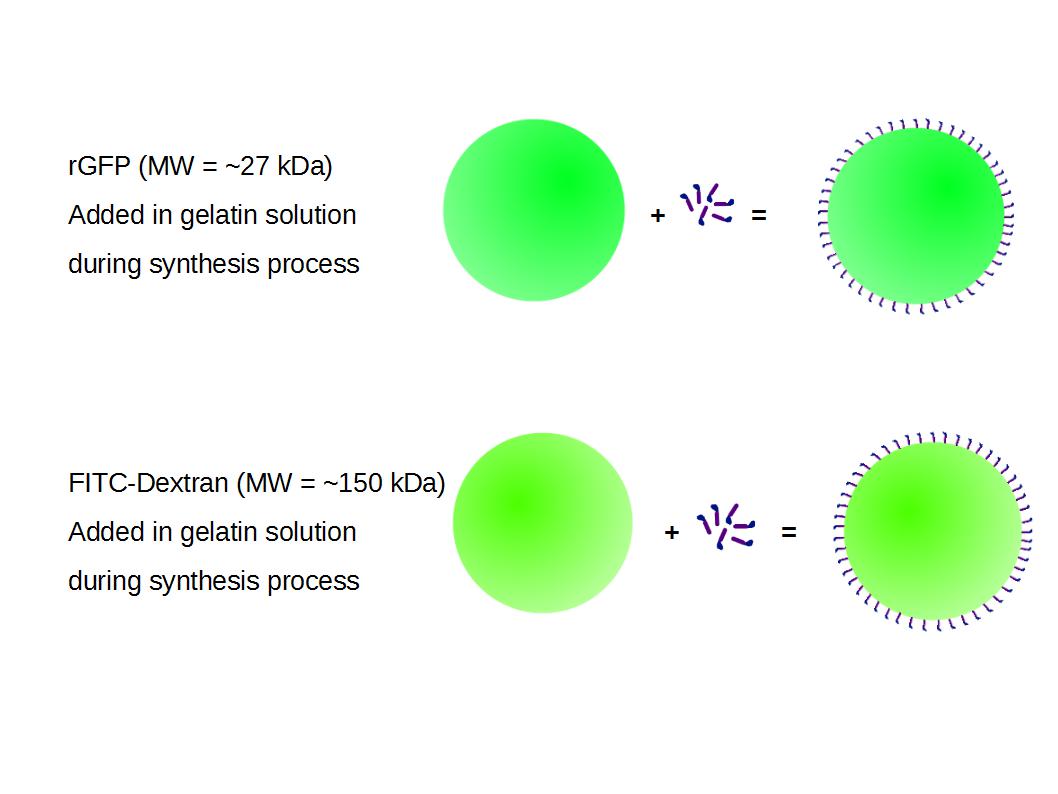

Making loaded nanoparticles :

We made two new batches of gelatin nanoparticles using the same modified two-step desolvation method. This time, we loaded them with recombinant GFP (molecular weight of ~25 kDa) and FITC-labeled dextran (molecular weight of ~150 kDa), both of which are fluorescent. The new nanoparticles have a mean diameter of about 200 nm, as shown by the DLS measurements. We tested the loading by microscopy. Though the FITC-dextran was successfully introduced into the nanoparticles, it was not the case for the recombinant GFP. It is probably due to its smaller molecular weight, which allowed it to come out of the nanoparticles. What's more, the procedure implies incubation in acetone, which denatures proteins.

Biotynylating loaded nanoparticles :

The FITC-dextran-loaded nanoparticles and the rGFP-loaded nanoparticles were biotinylated using the same activated biotin as for the previous nanoparticles. Biotinylation was successful, as shown by the ELISA-like assay.

We thought about making a third batch of nanoparticles, loading them with antibodies. However, we wanted to test first whether they could survive the low pH and the acetone, both of which they would have to endure during synthesis. We found that the low pH (2.5) didn't denature antibodies. However, the acetone does. Thus, what could be done is to chemically attach antibodies on the nanoparticles surface, as done with NHS-ester dye (see above). Something similar has been done at the National Taiwan University [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18436301 [3]].

Cargo transport alternatives :

During our project, two cargo transport strategies emerged: external labeling with a chemically activated cargo that directly reacts with the nanoparticles outer layer, or internal loading during nanoparticles synthesis. Both have their advantages and drawbacks. External loading is quick and can be achieved after synthesis. The release of the cargo only requires the digestion of the outer layer of the nanoparticles. However, the cargo must be chemically activated, i.e should ideally contain free sulfur radicals. Furthermore, with such a layout, the cargo is exposed to the environment. On the other hand, internal loading isolates the cargo. However, we saw that it requires a big protein and the cargo protein encounters denaturation during nanoparticles synthesis. This loading strategy would however still be very efficient for small resistant molecules comparable to FITC: they could be easily loaded after being attached to dextran.

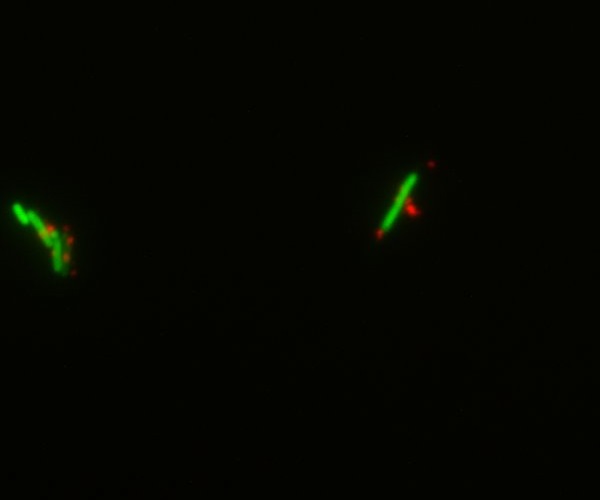

Linking nanoparticles to bacteria :

We decided to chemically attach streptavidin to bacteria (using streptavidin hydrazide) in order to be able to link biotinylated nanoparticles to them. This was done both on simple DH5-alpha cells and GFP-expressing E.coli. Though the cells were dead by the time we visualized them under the microscope, we could show that the nanoparticles indeed bind specifically to the bacteria. This gives a preview of what the final Taxi.Coli device could look like!

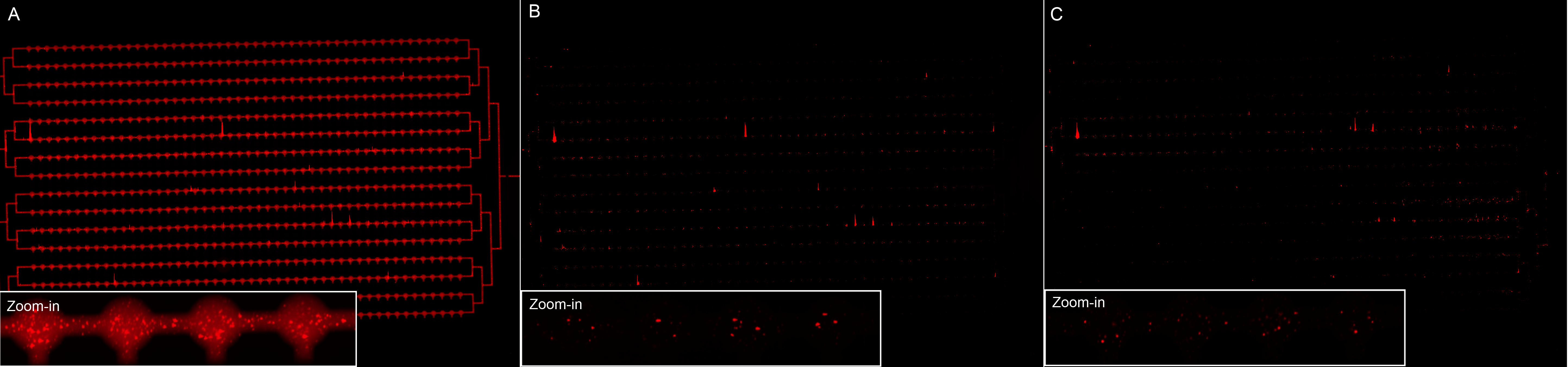

Microfluidics experiment :

We did a microfluidics experiment (MITOMI : Mechanically Induced Trapping Of Molecular Interactions) in order to visualize the nanoparticles digestion by the enzyme MMP2. We had some difficulties making the chip (one button was not working), so that in the end neutravidin was on the surface everywhere, instead of being only present on distinct spots. However, we were still able to see that our biotinylated nanoparticles were binding to neutravidin (Figure 17 A).

Additionally, it seems that the addition of MMP2 (in the first four channels) results in less fluorescence.

The experiment should however be repeated, since we had many problems with the chip. Indeed, another difficulty was that the buffers (flown on the lower part) affected the chip material, so that we don't have our controls.

To learn more about how we would continue, see Next Steps or Perspectives.

References :

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19534472 [1]] Layer-by-Layer-Coated Gelatin Nanoparticles as a Vehicle for Delivery of Natural Polyphenols,Shutava TG et al. (2009)

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16849014 [2]] Optimization of a two-step desolvation method for preparing gelatin nanoparticles and cell uptake studies in 143B osteosarcoma cancer cells, Azarmi S et al. (2006)

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18436301 [3]] Targeting efficiency and biodistribution of biotinylated-EGF-conjugated gelatin nanoparticles administered via aerosol delivery in nude mice with lung cancer, Tseng CL et al. (2008)

Below is a list of papers that we used as inspiration :

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20420904 [3]] Matrix-loaded biodegradable gelatin nanoparticles as new approach to improve drug loading and delivery, Ofokansi K et al. (2010)

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18848591 [4]] Polysaccharides-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems, Liu Z et al. (2008)

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22124766 [5]] Experiment on the feasibility of using modified gelatin nanoparticles as insulin pulmonary administration system for diabetes therapy, Zhao YZ et al. (2012)

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/516287238 [6]] Preparation and evaluation of thiol-modified gelatin nanoparticles for intracellular DNA delivery in response to glutathione, Kommareddy S, Amiji M. (2005)

"

"