Team:UCLA/Project/NaturalSystem

From 2013.igem.org

Michaelc1618 (Talk | contribs) |

Michaelc1618 (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

<h4>Comparable Systems in Nature</h4> | <h4>Comparable Systems in Nature</h4> | ||

| - | <p>A | + | <p>A classic example of natural diversity generation is the Human immune system. Humans can make more than 10<sup>12</sup> different antibody molecules. One of the cells they make are B cells. With repeated stimulation, B cells can make antibodies that bind to an antigen with higher affinity. B cells can alter the tail region of the antibody they make, while keeping the antigen-binding site unchanged. This allows the B cell to switch from making one class of antibody to another without changing the antigen-specificity of the antibody. Antibody genes are assembled from separate gene segments during B cell development. V, J, and D gene segments that encode for antibody chains are combined to diversify antigen-binding sites of antibodies (Alberts).</p> |

Revision as of 01:32, 28 September 2013

Contents |

The Natural Host

Bordetella is the natural host of the BPP-1 bacteriophage. It expresses a protein on its surface, pertactin, that BPP-1 binds to in the first step of the infection process. However, Bordetella does not always express pertactin. It cycles between two phases: Bvg+ and Bvg-. Pertactin is only expressed in the Bvg+ phase, while in the Bvg- phase, pertactin expression is inhibited. Infection by BPP-1 during this phase is much less common, but it still occurs (Liu). This indicates that the BPP-1 virus has a mechanism for changing its host specificity, and thus, the binding properties of the proteins on its tail fibers.

The Virus

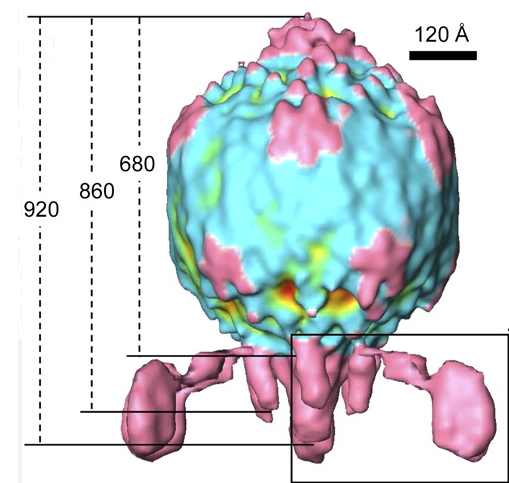

The BPP-1 virus is a bacteriophage belonging to the Podoviridae family. It has an icosahedral head with T=7 symmetry, and a short, noncontractile tail with six tail “spikes” attached to tail fibers. At the end of these tail fibers are major tropism determinant (Mtd) proteins, which bind to the pertactin proteins expressed on the surface of Bordetella. The Mtd protein does not display high affinity for pertactin, but the multiple Mtd proteins possessed by each phage particle coupled with the flexibility of the tail fibers allow BPP-1 as a whole to have high avidity for its host (Liu). Following infection, the virus is lytic, and destroys the bacterial host to release more copies of itself (ViralZone).

Diversity Generation

The BPP-1 phage contains a diversity generating retroelement (DGR) for diversifying its Mtd protein. DGRs generate variability in the viral receptor protein that specifies tropism for ligand molecules, and encode polypeptides that are designed to tolerate sequence variation. A C-type lectin fold displays amino acid sequence variability. The lectin fold provides a static scaffold that helps balance diversity with protein stability. A reverse transcriptase mediates the exchange between two repeats, a variable repeat (VR) and a template repeat (TR).

The BPP-1 genome contains a variable repeat (VR) of 134 base pairs on the gene coding for the Mtd. This variable repeat is variable across every specimen of BPP-1, with variations isolated to 23 discrete nucleotides. Downstream from the variable repeat is the template repeat (TR), which serves as a master copy and is never permanently altered in wild-type phage (Medhekar).

Occasionally, during the viral assembly process, the TR is transcribed, and then reverse transcribed by a reverse transcriptase coded for by the brt gene further downstream from the mtd gene. This process introduces site mutations at the 23 extremely specific nucleotide locations. These nucleotides are all adenines, and are changed to any of the four possible nucleotides. The resulting cDNA strand is then directed to the location of the VR and integrated into the genome, replacing the VR itself (Guo). All of this results in the assembled viral particle having a different sequence in the mtd gene, and thus a different Mtd protein that is capable of binding to another target on the surface of Bordetella.

Comparable Systems in Nature

A classic example of natural diversity generation is the Human immune system. Humans can make more than 1012 different antibody molecules. One of the cells they make are B cells. With repeated stimulation, B cells can make antibodies that bind to an antigen with higher affinity. B cells can alter the tail region of the antibody they make, while keeping the antigen-binding site unchanged. This allows the B cell to switch from making one class of antibody to another without changing the antigen-specificity of the antibody. Antibody genes are assembled from separate gene segments during B cell development. V, J, and D gene segments that encode for antibody chains are combined to diversify antigen-binding sites of antibodies (Alberts).

Alberts, B., et al. "The Generation of Antibody Diversity." ''Molecular Biology of the Cell.'' New York: Garland Science, 2002. Print.

Dai, W., et al. "Three-dimensional structure of tropism-switching Bordetella bacteriophage." PNAS. 107.9 (2010):4347-52. Print.

Guo, H., et al. "Target Site Recognition by a Diversity-Generating Retroelement." PLoS Genetics. 7.12 (2011). Web.

Liu, M., et al. "Reverse Transcriptase-Mediated Tropism Switching in Bordetella Bacteriophage." Science. 295.5562 (2002): 2091-4. Print.

Medhekar, B., J. Miller. "Diversity-Generating Retroelements." Curr Opin Microbiol. 10.4 (2007):388-95. Print.

"Podoviridae." ViralZone. ExPASy, n.d. Web. 2013.

"

"