Header

Contents |

Sensing

Overview

The idea of this module was to transform bacteria with a plasmid that contains a promoter which senses a specific signal. Once this promoter senses the signal, it would initiate transcription of an enzyme which degrades the nanoparticle, thus releasing its contents. We decided to use pH as the specific trigger that activates the promoter. As a proof of principle, we inserted three different promoters into three plasmids in front of the BioBrick BBa_I746916 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I746908 BBa_I746916, Main Page]) which encodes superfolded GFP. Then, we transformed cells with these plasmids and let them grow in media with different pHs in order to check the expression.

Experiments

We chose the following three pH sensitive promoters:

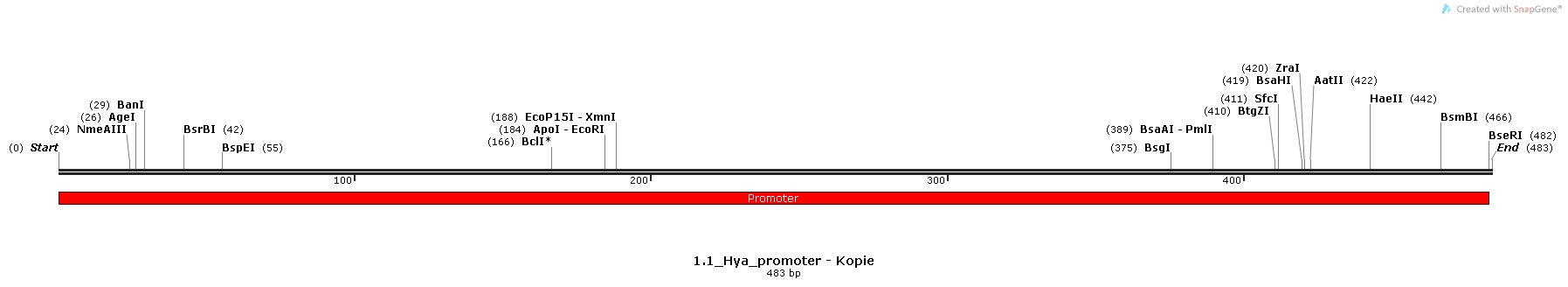

1.) Hya-promoter, isolated from the Escherichia Coli K-12 MG1655 strain [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1111002 BBa_K1111002]

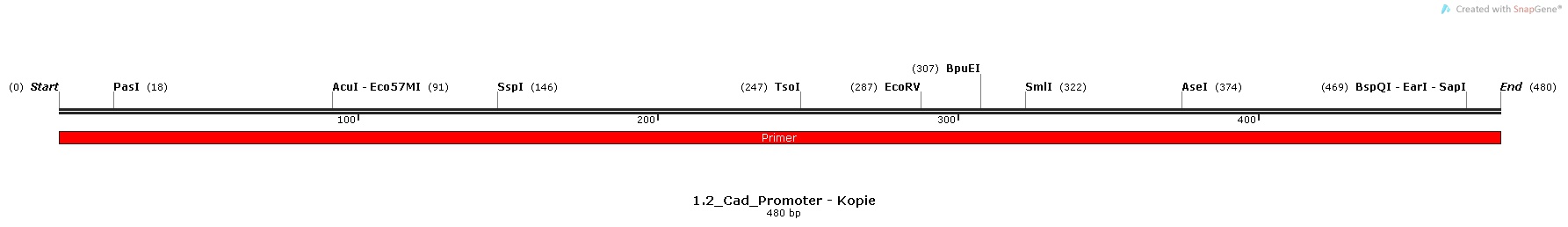

2.) Cad-promoter, isolated from the Escherichia Coli K-12 MG1655 strain [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1111004 BBa_K1111004]

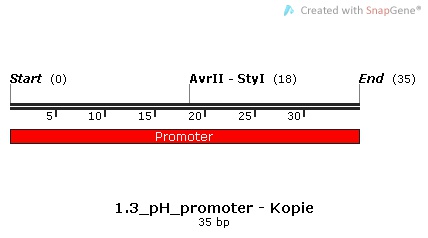

3.) BioBrick BBa_J23119, a constitutive promoter that was made by the 2006 Berkley team. [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1111005 BBa_K1111005]

Promoter Sequences

Restriction Digest

We digested the plasmid containing the biobrick BBa_I746908 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I746908 BBa_I746908]) which would serve as backbone for our constructs.

PCRs and Gibson Assemblies

All the promoters were isolated by PCR and then assembled into the pSB1C3 Plasmid in front of the superfolded GFP.

Then, each of the constructs was used to transform DH5-alpha competent cells, which were first plated on chloramphenicol containing LB agar plates for selection of positive transformants, and then incubated into media with different pHs.

We used four media:

1.) LB-Chloramphenicol with a final pH of 5 (Adjusted with 10X MOPS+HCl)

2.) LB-Chloramphenicol with a final pH of 6 (Adjusted with 10X MOPS)

3.) LB-Chloramphenicol with a final pH of 7 (Adjusted with water)

4.) LB-Chloramphenicol with a final pH of 8.5 (with 10X HEPES)

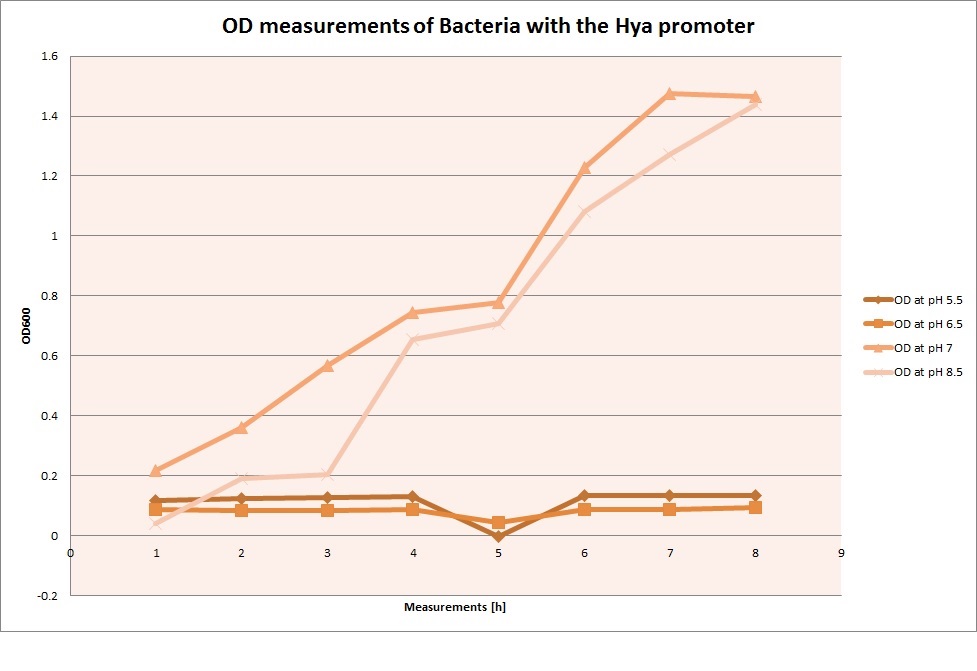

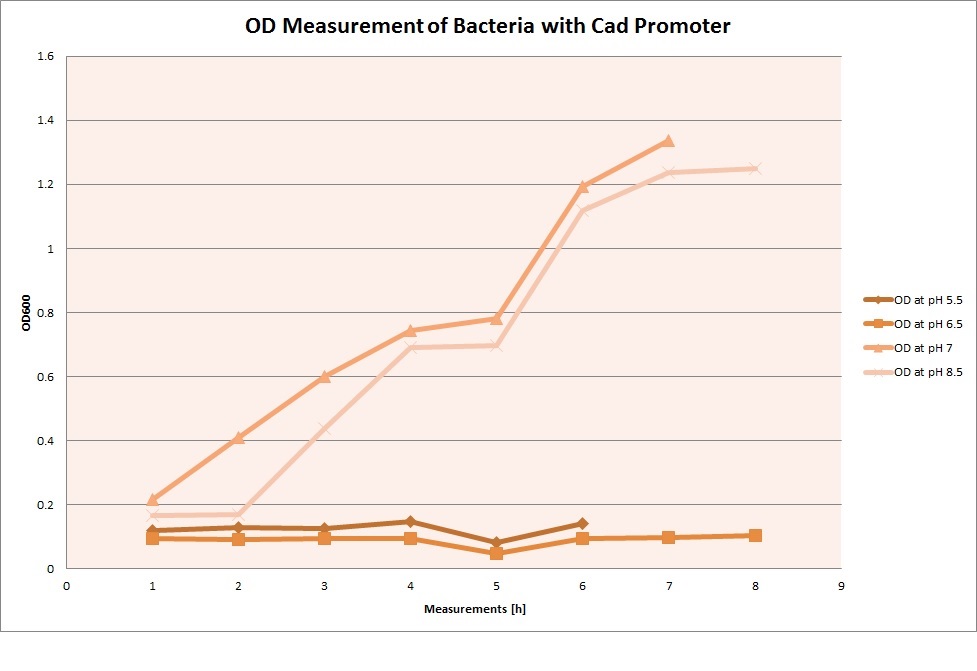

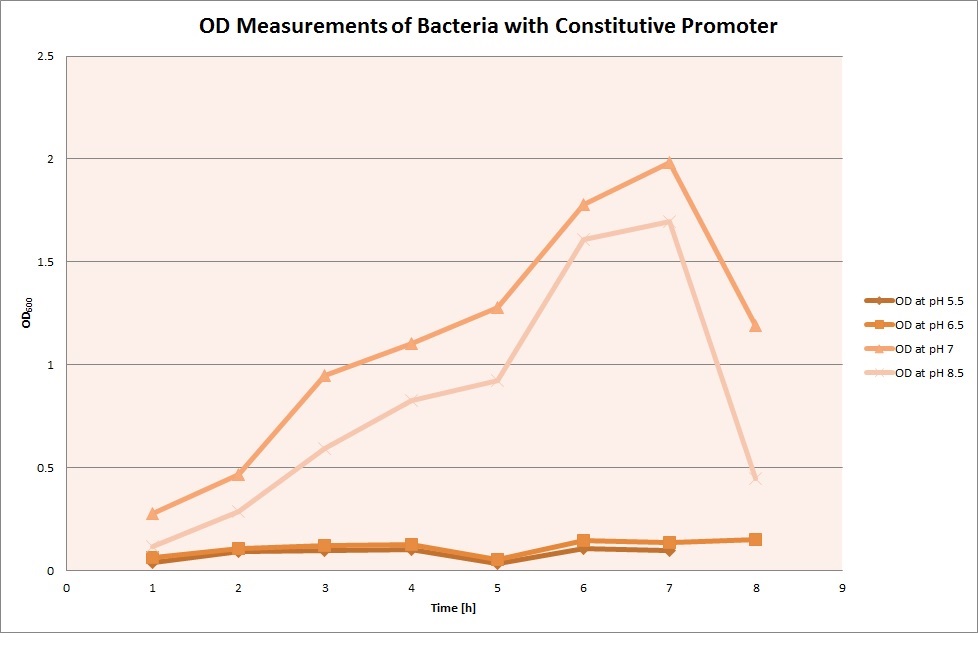

For each medium, we measured the OD of the cells. This helped us establish whether a low expression of GFP was really due to the fact that the promoters did not work, or simply resulting from the cells dying before they could initiate transcription and translation of the protein. It would also tell us whether an increase of fluorescence was only due to an accumulation of bacteria or to the actual accumulation of GFP.

OD measurements

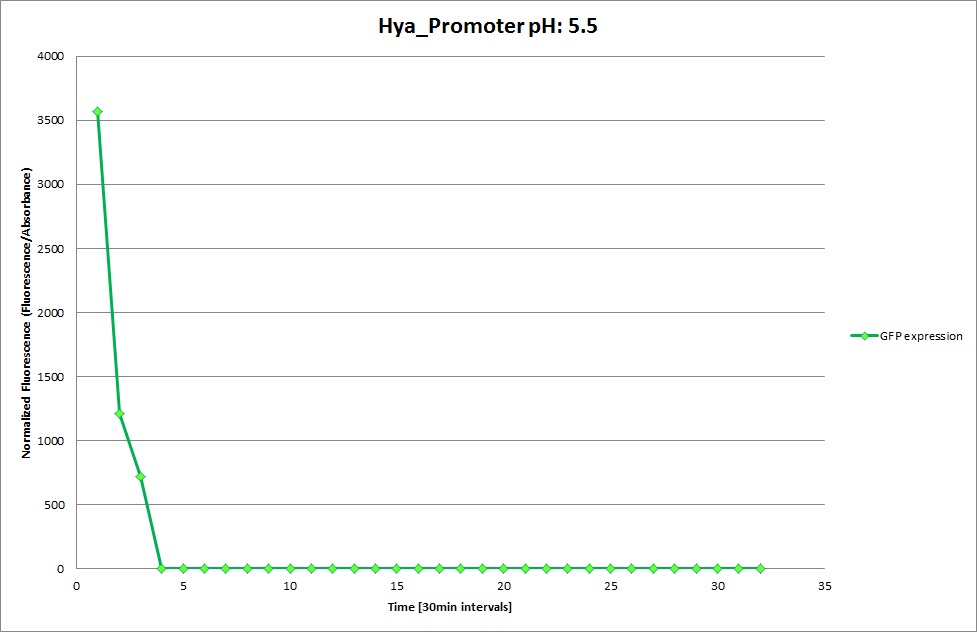

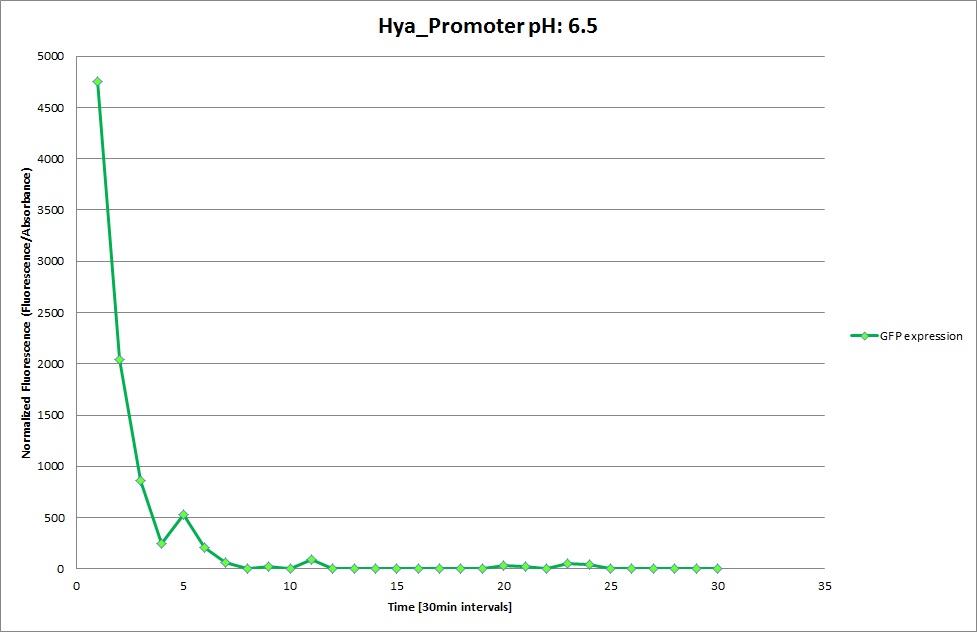

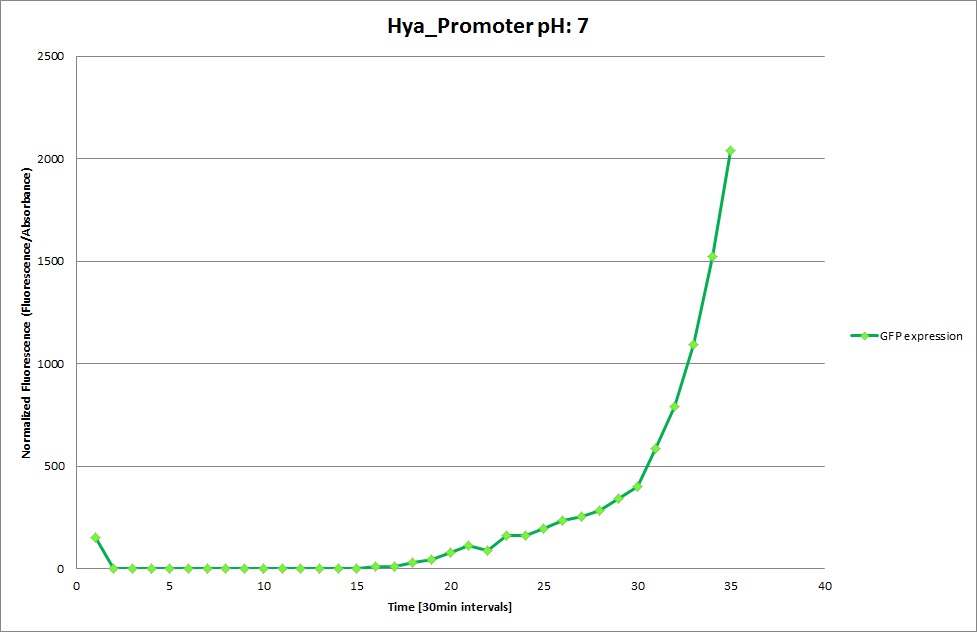

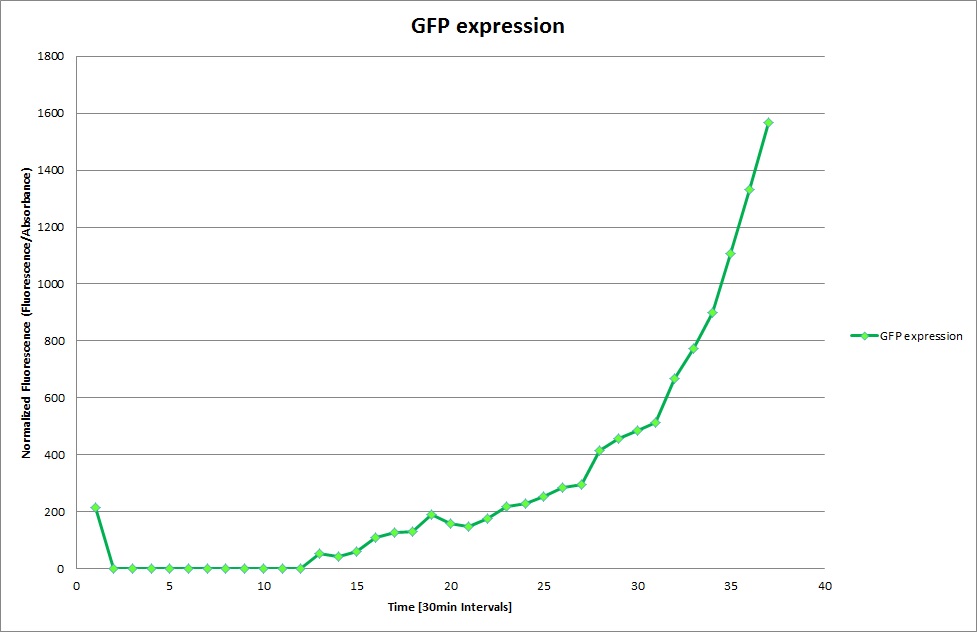

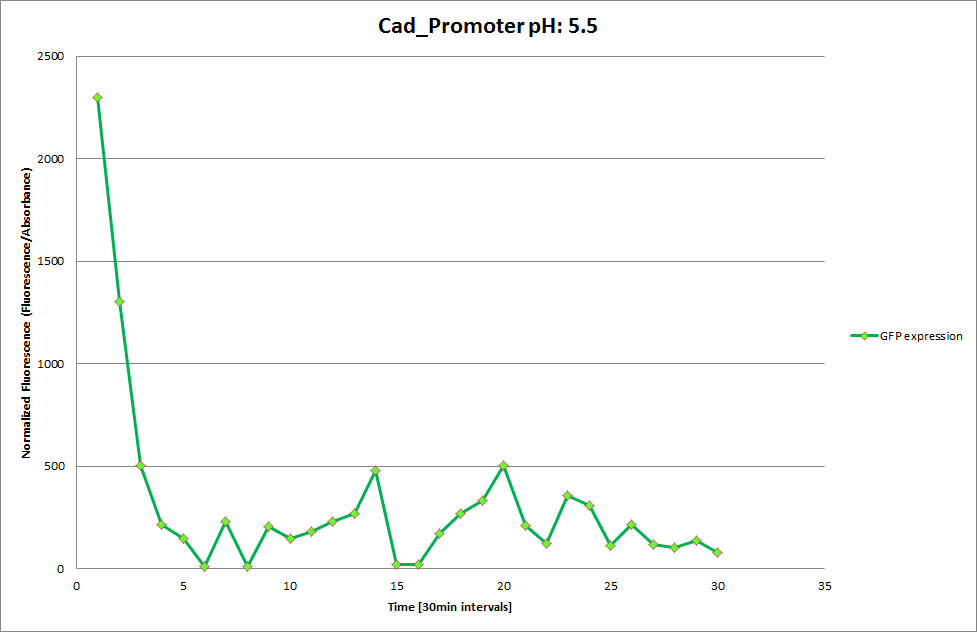

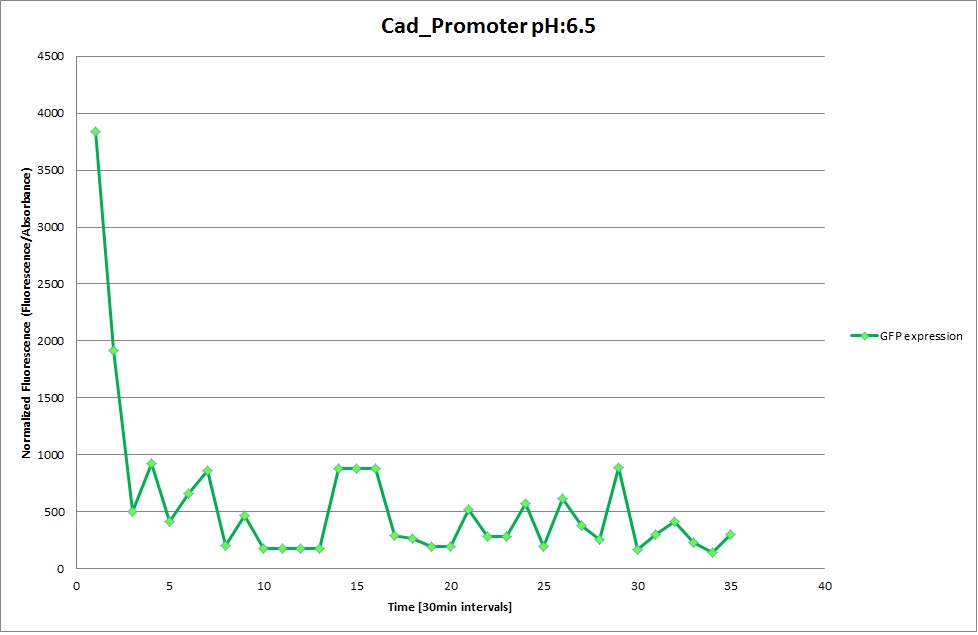

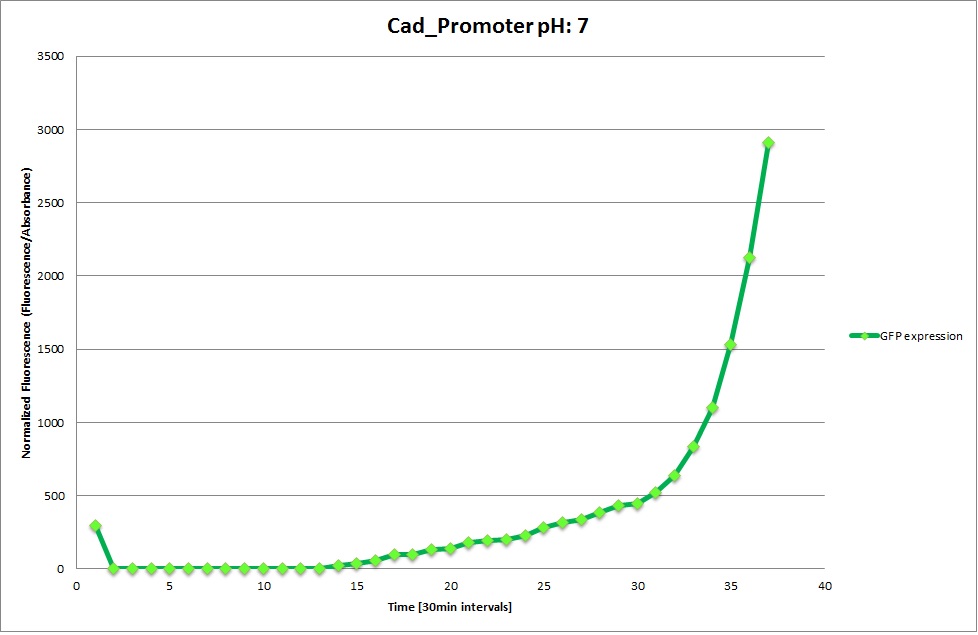

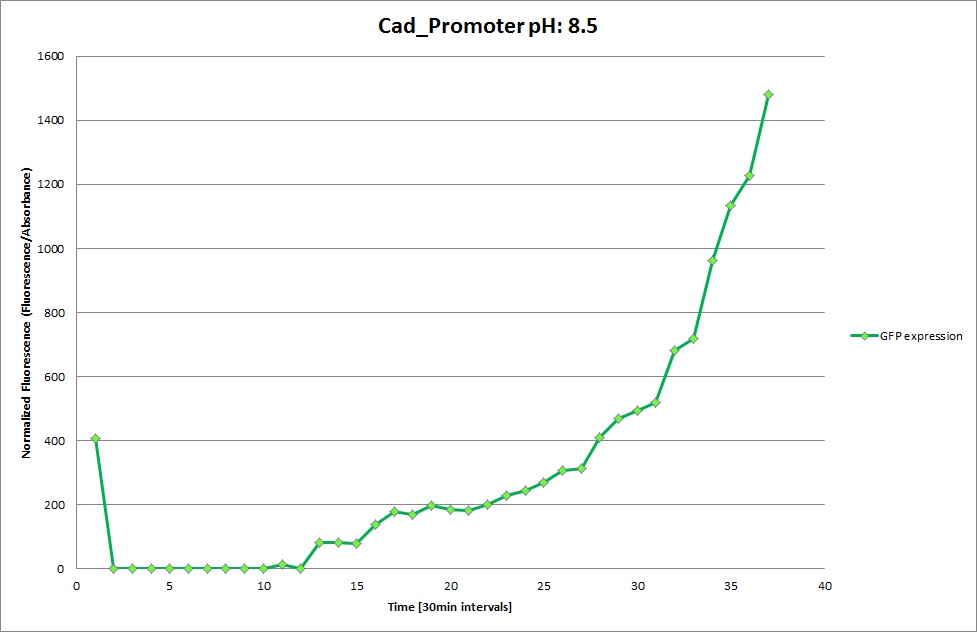

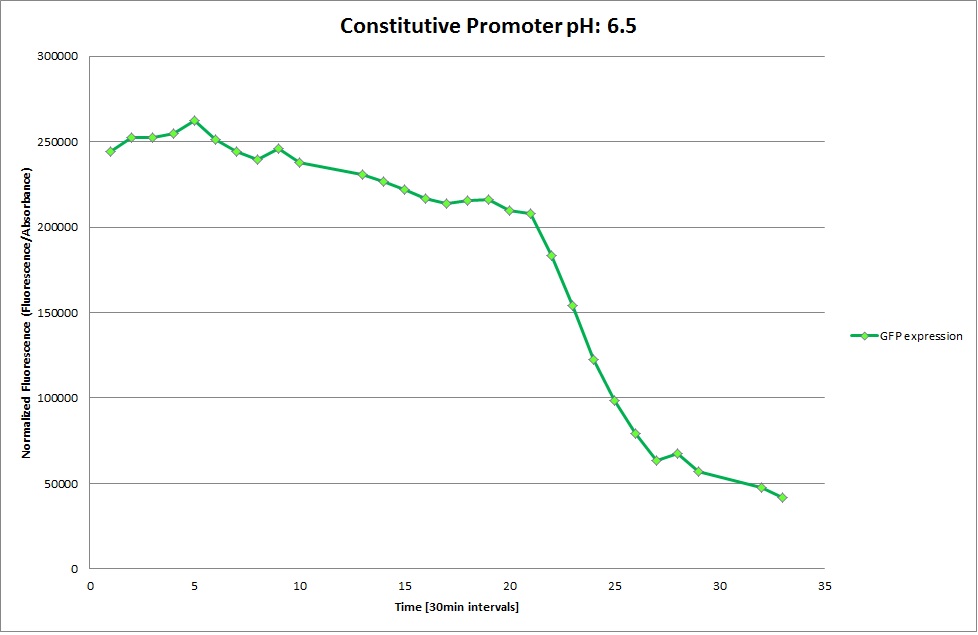

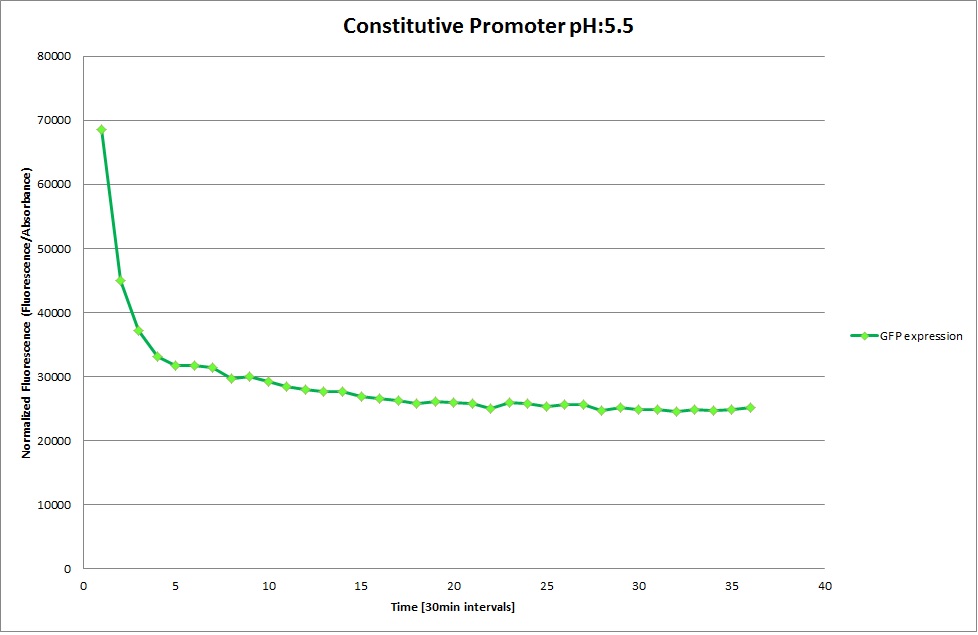

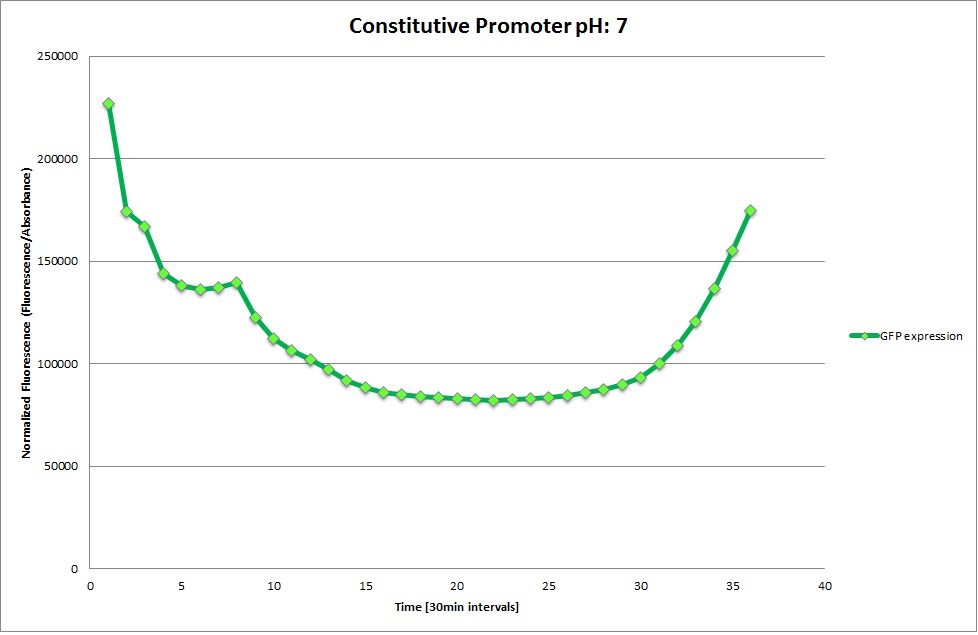

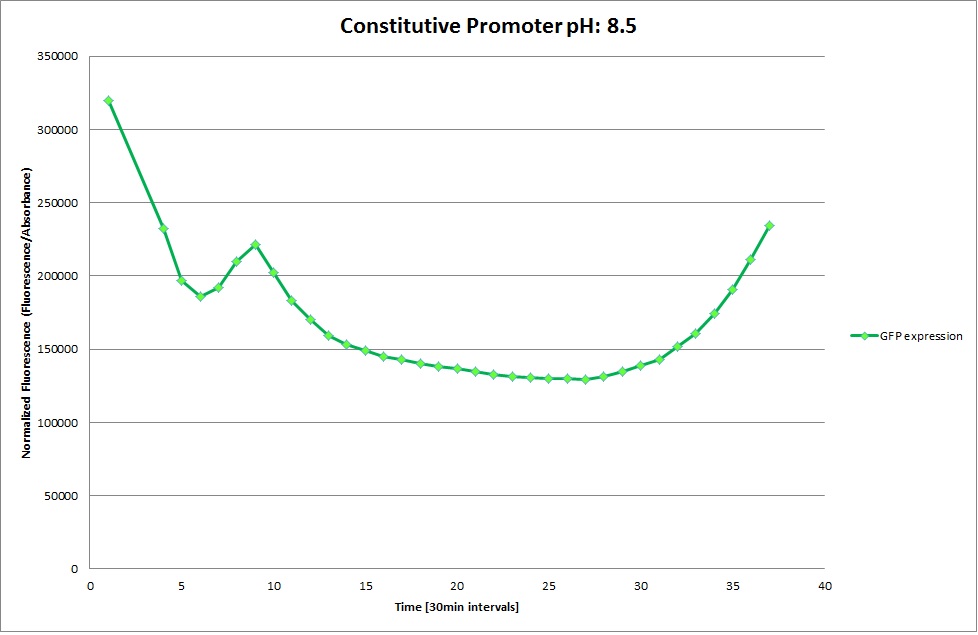

GFP expression was measured using a plate reader. We made three replicates for each promoter with each pH. Both the fluorescence and the 1:600 absorbance were measured, in order to normalize the obtained fluorescence. Then, the average for each replicate was calculated and used to establish a curve depicting GFP expression within each medium.

GFP Measurements

Hya Promoter

Cad Promoter

Constitutive Promoter

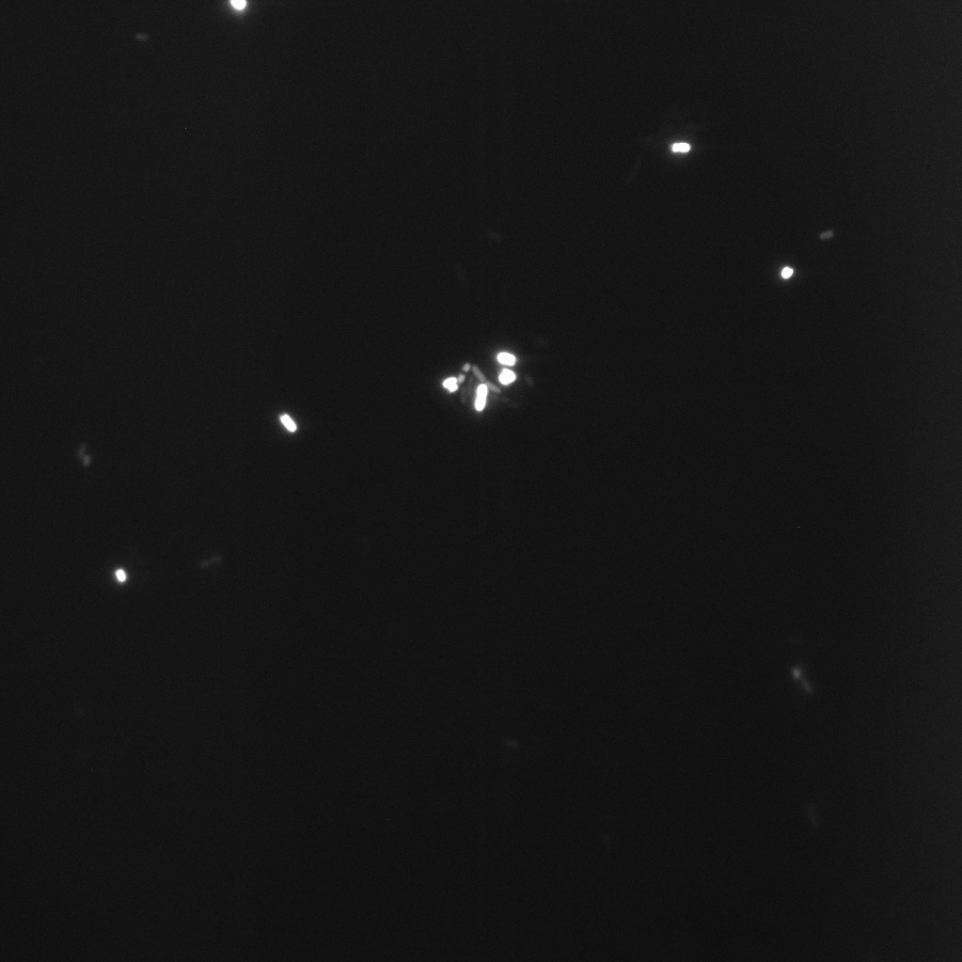

Microscopy

The Cells were also looked at under a microscope to qualitatively study their GFP expression.

Hya Promoter

Cad Promoter

Constitutive Promoter (Positive Control)

Note

We overexposed some of the images to be sure that there was no fluorescence in the bacteria in these media.

Expected outcome

The promoters Hya and Cad were supposed to initiate transcription upon external acidification, which would then cause the bacteria to express superfolded GFP and turn bright green. The biobrick BBa_J23119, being a constitutive promoter, would turn the bacteria green independently of their medium. For our project, the promoters were inserted in front of a gelatinase so that the latter would be expressed upon arrival in an acidic medium. The bacterium would then secrete the gelatinase causing the degradation of the naonoparticle and the release of its contents.

Results

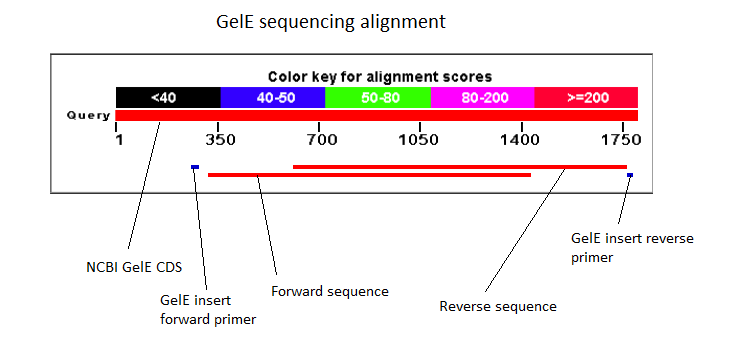

We successfully managed to PCR amplify each of the three promoters as well as to insert them by Gibson Assembly into the pSB1C3 plasmid so that they would control the expression of superfolded GFP. These assemblies were all successful, which was determined by sequencing the plasmid isolated from the positive transformants on the plate. This sequencing result showed a 100% match between the reference promoter sequence and the inserted sequence that the bacteria contained. Also, the bacteria containing the biobrick promoter turned green on the plates as well as in liquid culture, as expected.

Discussion

GFP expression under the hya and the cad promoters

From the measurements we made on the plate reader, we were not able to conclude whether the promoters are really induced at low pH as the cells died very quickly. This was also supported by the OD measurements we took. On those graphs one can see very clearly that the cells which are in the acidic media die almost immediately. Furthermore, there was some expression in both the neutral and the basic medium. This would indicate that the promoter is either a constitutive promoter or that it is inducible but leaky.

Comparing these graphs with the microscopy pictures, one cannot say conclusively that the promoter is inducible by pH. Even though under the microscope there are only fluorescent bacteria at acidic pH, the results from the plate reader clearly indicate that there are also fluorescent bacteria at neutral and high pH. However, one can see a trend that for both the hya and the cad promoter, the fluorescence is strongest at acidic pH and weakest at basic pH under the microscope. This trend cannot be seen in the Plate Reader measurements, as the bacteria at low pH die before being able to express GFP.

Using the constitutive promoter as a positive control one can see that both hya and cad are weak promoters, as the fluorescence in the bacteria with the constitutive promoter is much stronger in acidic, neutral and basic media than the fluorescence in bacteria containing the hya or the cad promoter. Furthermore, a comparison with the constitutive promoter again supports the hypothesis that the bacteria grow best at neutral pH, as there are much more bacteria at pH 7 and at pH 6.5 or 8.5.

Conclusion

Thus, we can conclude that the hya promoter and the cad promoter work, in the sense that they in fact induce expression of GFP. But from our data, we were not able to conclusively say that they are inducible by low pH.

Nevertheless, we were able to show that they are weak promoters that can be used to express a protein that should be present at low concentrations.

With respect to our project

In order to be sure that hya and cad are induced only at low pH, we would need to do further testing. As soon as their inducibility would be confirmed, we would insert them by gibson assemly in front of either GelE gelatinase or MMP2 gelatinase. Upon arrival in a medium with pH below 7 the enzyme would be synthesized and released.

References:

[http://jb.asm.org/content/181/17/5250.full [1]] Journal of Bacteriology

Response of hya Expression to External pH in Escherichia coli

Paul W. King and Alan E. Przybyla

J.Bacteriol. 1990

[http://jb.asm.org/content/173/15/4851.abstract?sid=2a119bc7-0c26-4543-a671-d3a50521253f [2]] Journal of Bacteriology

Mutational analysis and charecterization of the Escherichia coli hya operin, which encodes [NiFe] hydrogenase1

N K Menon, J Robbins, J C Wendt, K T Shanmuagam and A E Przybyla

J. Bacteriol 1991

[http://jb.asm.org/content/174/8/2659.short [3]] Journal of Bacteriology

Nucleotode Sequence of the Escherichiea coli cad Operon: a system for neutralization of Low Extracellular pH

Shi-Yuan meng and George N. Bennett

J. Bacteriol 1992

[http://jb.asm.org/content/174/8/2670.short [4]] Journal of Bacteriology

Regulation of the Escherichia coli cad Operon: Location of a Site Required for Acid Induction

Shi-Yuan meng and George N. Bennett

J. Bacteriol 1992

Effecting

Overview

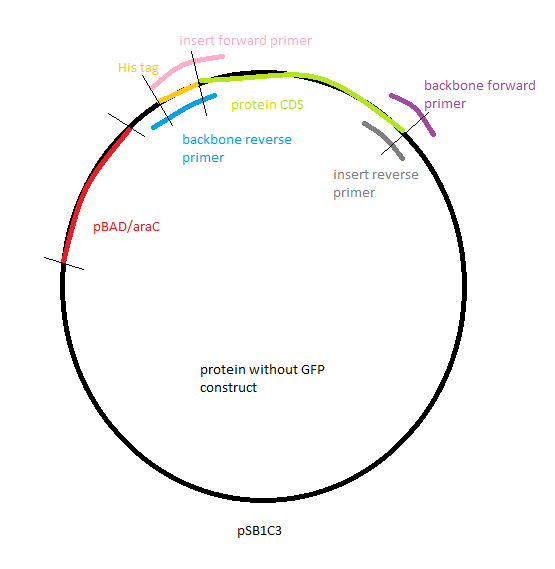

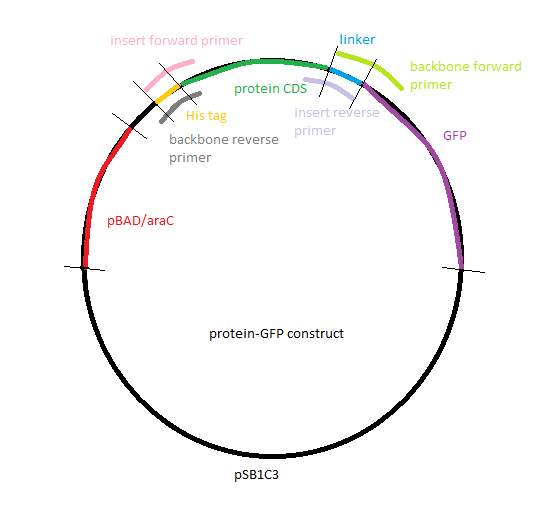

The goal of the effecting part was to build a plasmid containing an arabinose-inducible promoter driving a tagged enzyme able to cleave gelatin, the polymer used to build our nanoparticles. We chose three different enzymes that were inserted into part BBa_I746908([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I746908 [BBa_I746908, Main Page]) either between the promoter and GFP or replacing the GFP. All of the constructs were designed to have a His tag at the beginning of the protein so we could extract and purify our expressed protein.

We would then transform cells with our construct, make them express the gelatinase by inducing the promoter and then isolate and purify the protein.

Experiments

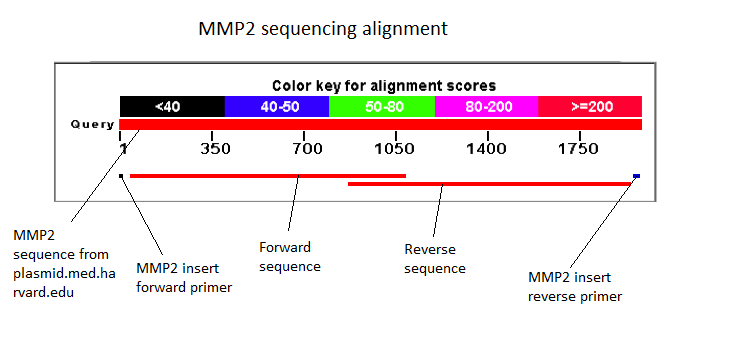

The three different enzymes that we chose to use were gelatinase E (gelE) from Gram positive bacterium E.faecalis [http://www.example.com [1]], metalloprotease 2 (MMP2) from H. sapiens [http://plasmid.med.harvard.edu/PLASMID/GetCloneDetail.do?cloneid=2849&species=Homo%20sapiens [2]] and metalloprotease 9 (MMP9) from M. musculus. We ordered the genomic DNA of E.faecalis as well as two plasmids containing the CDSs of MMP2 and MMP9 from plasmid.med.harvard.edu.

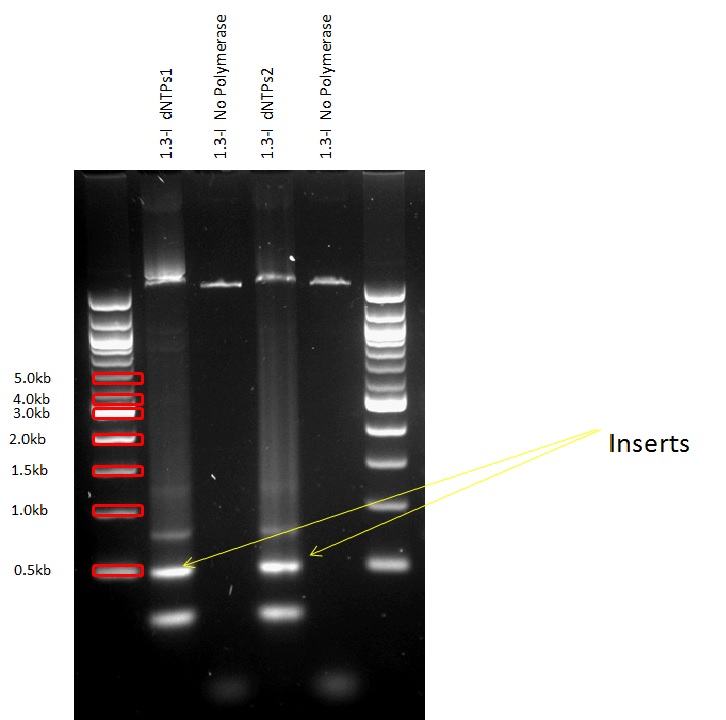

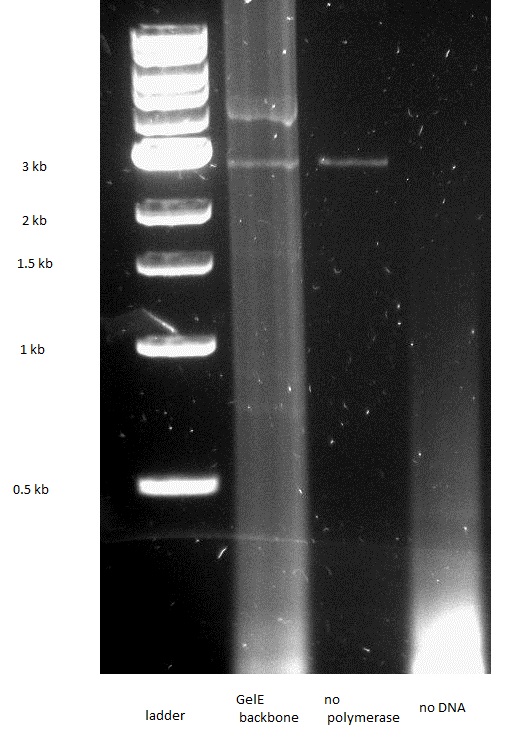

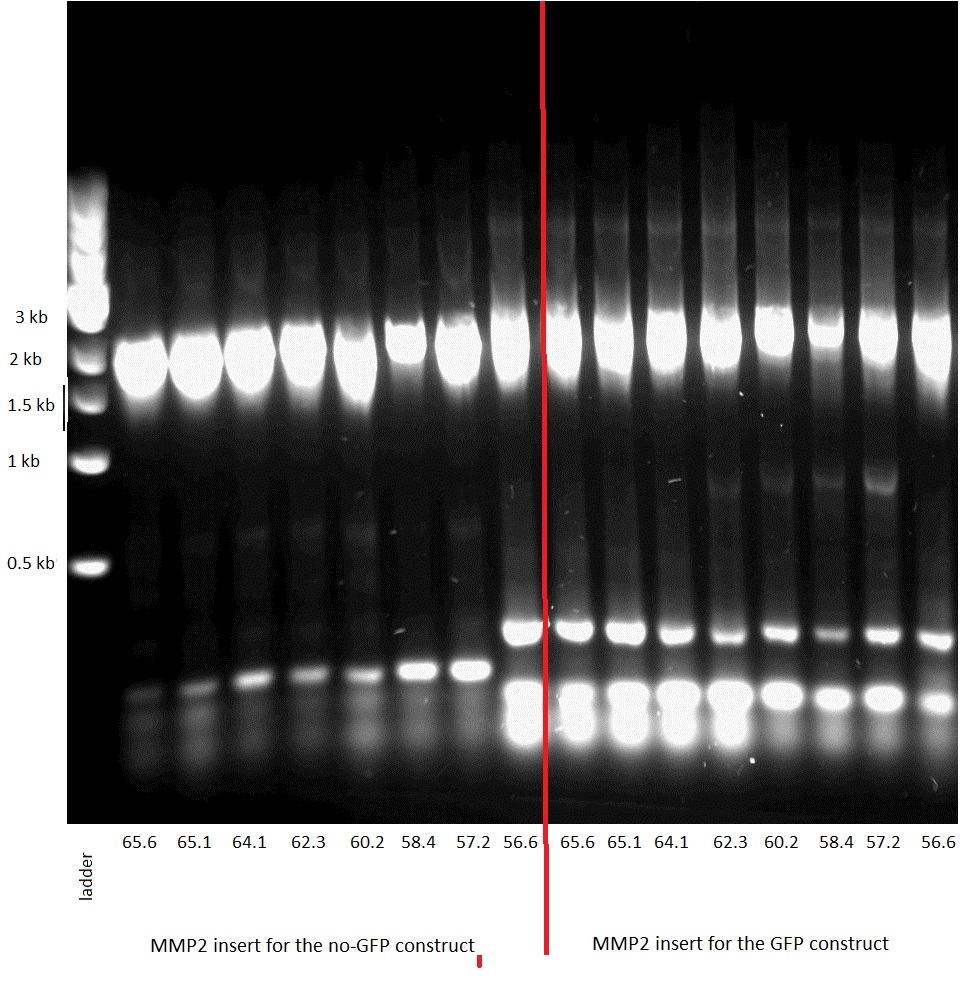

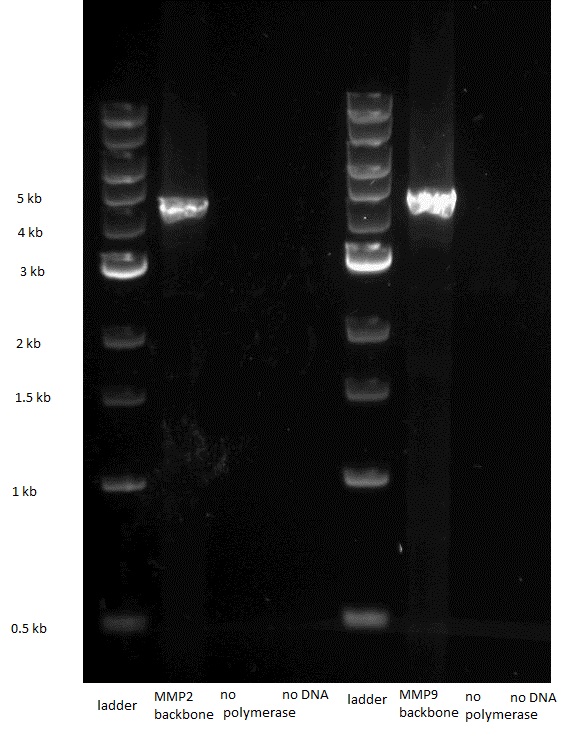

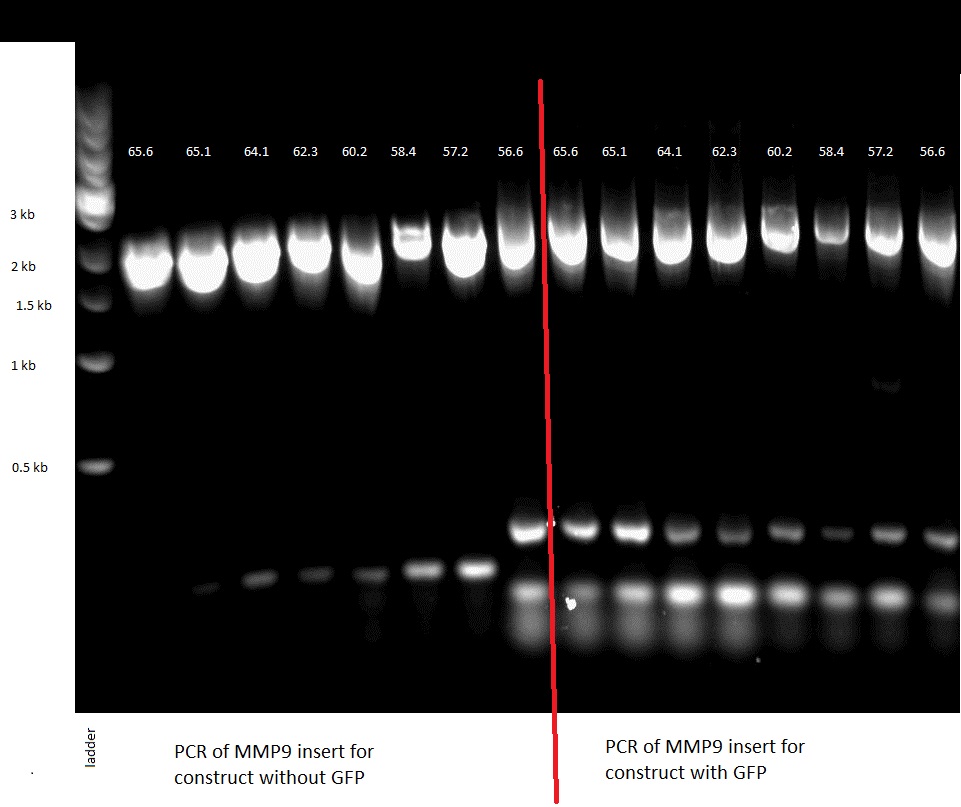

PCR

We first amplified the CDS of our three proteins by PCR, using the primers described in the "Strategy" paragraph. The expected weights for our products were: 1,5 kb for the GelE insert, 2 kb for the MMP2 and MMP9 inserts, 3.2 for the backbone without GFP and 4.2 kb for the backbone still containing GFP. The PCRs for the backbones having the GFP removed did unfortunately not work, so we had to leave the three constructs that needed them behind.

Then, we proceeded to a PCR purification.

Gibson Assembly

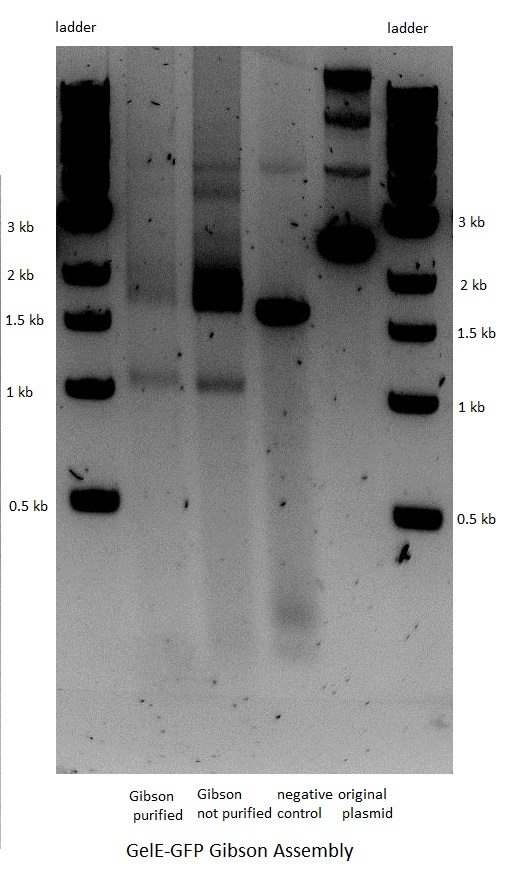

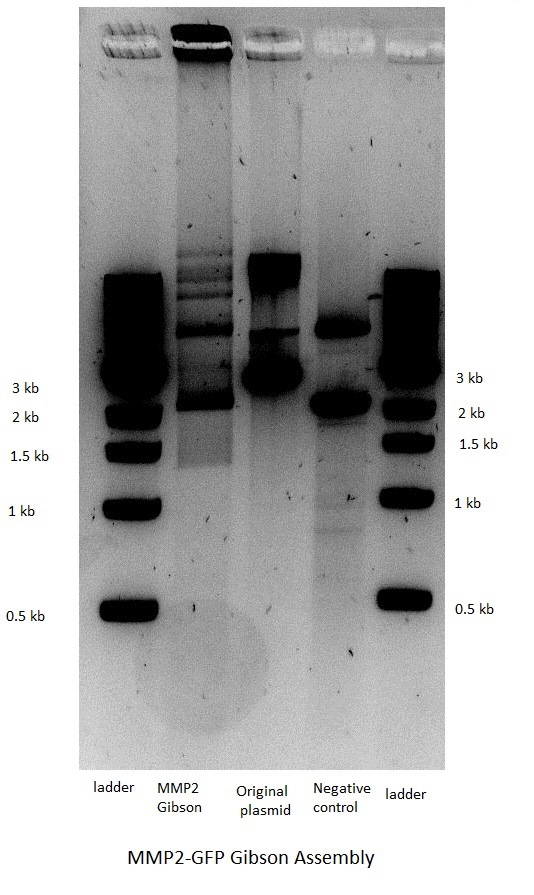

The next step was the Gibson assembly reaction which would put together the inserts and their corresponding backbones, thus assembling our constructs. The reaction was performed only for the constructs that were built to have the GFP reporter in the plasmid, the three other constructs being left aside due to a PCR issue.

The assembly worked for both the GelE-GFP and MMP2-GFP constructs, but not for MMP9.

The expected weights of the constructs were of 5.7 kb for the GelE-GFP and 6.2 kb for the MMP2-GFP. The band at 6 kb is clear for the MMP2-GFP construct, but the one at 5.7 isn't really visible for the GelE-GFP construct. We would be able to check for the presence of both constructs at the next step, after the minipreps were done.

Transformation and sequencing

We then transformed bacteria with the plasmids, isolated them and sent the minipreps for sequencing. The sequencing revealed the presence of an unexpected STOP codon just before the start of the GFP sequence. We still performed the glowing assay by adding 50ul of 20% arabinose to the 5ml culture medium in which we had grown the transformed bacteria overnight but the result came out negative.

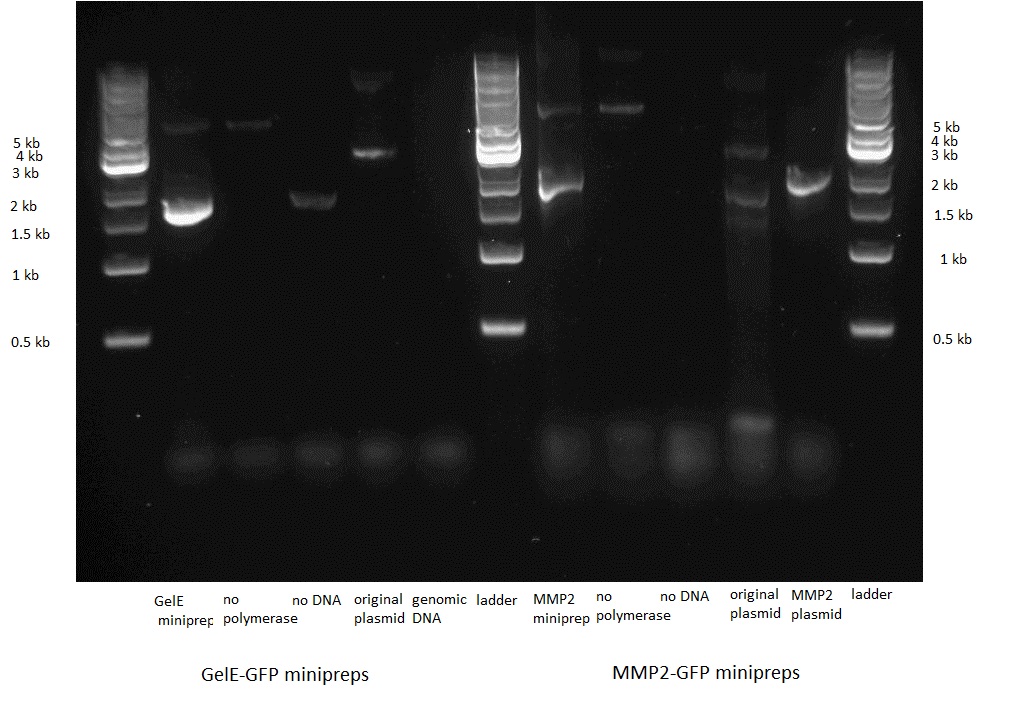

The minipreps show the presence of the two expected constructs at 5.7 kb and 6.2 kb, repectively.

Western Blot

The next assay to test the expression and secretion of our fusion proteins was a Western Blot, performed on the medium and cell lysate fractions of our liquid cell culture. The antibody used to detect our protein was an anti-His tag antibody, which was supposed to detect the his tag that had been added to the CDS of our fusion proteins. This assay unfortunately also came out negative. Also, we were unable to check for the presence of the His tag with the sequencing because the primers we used to do it were the same as for the Gibson. Thus, the sequencing starts a bit downstream of the primers, not sequencing them. However, their sequence was correct when we checked the order we had made.

His-tag purification and SDS-PAGE

A His tag purification method under native conditions using a Ni-NTA spin kit was performed. The native conditions were chosen because we wanted to perform a digestion assay with the purified protein on the nanoparticles to assess their digestion capacities.

The lysates, flow-through, wash and final eluate (supposed to contain the purified protein) were kept and analysed with a NanoDrop before being used for an SDS-PAGE. The NanoDrop revealed that the eluates contained no protein, but that the wash fraction contained about 0.4 mg/ml of protein. The two possible reasons for this were: 1) the His tag was not properly added to the protein CDS (PCR mutation, ...) or 2) the His tag was hidden in the protein structure and could not bind to the column since the purification was done under native conditions. Therefore, the SDS-PAGE could reveal the presence of our protein by comparing the SDS-PAGE results of the protein from the arabinose-induced cell culture and those from the un-induced cells (negative control).

Unfortunately, the experiment did not work due to a Coomassie stain issue: nothing could be visualized.

Discussion and Future

We unfortunately could not come to a satisfying final result in the effecting part of the project because we could not prove that the plasmids actually conferred to the bacteria the ability to secrete a gelatin-degrading protein. We can later perform the digestion assay with the wash fraction of the Ni-NTA purification to see whether a gelatin-degrading protein is indeed present in it. Also, the next experiment would be to redo the SDS-PAGE on the remaining of the Ni-NTA purification.

References & Information

GelE-GFP insert forward primer: 5'-ATG CACCACCACCACCACCAC AAG GGA AAT AAA ATT TTA TAC CAT TTT A-3'

GelE-GFP insert reverse primer: 5'-ACC ACC AGA TTG AAA ATA CAA ATT TTC ACC TTC ATT GAC CAG AAC AGA TTC-3'

BBa_I746908 backbone forward primer: 5'-GGT GAA AAT TTG TAT TTT CAA TCT GGT GGT GAT GCG TAA AGG CGA AGA GCT-3'

BBa_I746908 backbone reverse primer: 5'-ATT TCC CTT GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG CAT TAG TAT TTC TCC TCT TTC TCT AGT AGC TAG-3'

MMP2-GFP insert forward primer: 5'-ATG CACCACCACCACCACCAC GAG GCG CTA ATG GCC C-3'

MMP2-GFP insert reverse primer: 5'-ACC ACC AGA TTG AAA ATA CAA ATT TTC ACC GCA GCC TAG CCA GTC GGA TTT GAT-3'

BBa_I746908 backbone forward primer: 5'-GGT GAA AAT TTG TAT TTT CAA TCT GGT GGT GAT GCG TAA AGG CGA AGA GCT-3'

BBa_I746908 backbone reverse primer: 5'-TAG CGC CTC GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG CAT TAG TAT TTC TCC TCT TTC TCT AGT AGC TAG-3'

"

"