Team:KU Leuven/Project/Glucosemodel/EBF

From 2013.igem.org

Secret garden

Congratulations! You've found our secret garden! Follow the instructions below and win a great prize at the World jamboree!

- A video shows that two of our team members are having great fun at our favourite company. Do you know the name of the second member that appears in the video?

- For one of our models we had to do very extensive computations. To prevent our own computers from overheating and to keep the temperature in our iGEM room at a normal level, we used a supercomputer. Which centre maintains this supercomputer? (Dutch abbreviation)

- We organised a symposium with a debate, some seminars and 2 iGEM project presentations. An iGEM team came all the way from the Netherlands to present their project. What is the name of their city?

Now put all of these in this URL:https://2013.igem.org/Team:KU_Leuven/(firstname)(abbreviation)(city), (loose the brackets and put everything in lowercase) and follow the very last instruction to get your special jamboree prize!

E-β-Farnesene

In this part, we will give some more information about the E-β-farnesene (EBF) part of the project. EBF is an alarm pheromone, released by almost all of the 4000 aphid species known thus far in response to the presence of predators (e.g. the ladybug) or other disturbances. In response to the produced EBF, aphids change their metabolism and turn into a winged form, allowing them to "flee the scene" and thus increase their survival rate. Apart from the short term repelling effect, EBF can also cause long term effects: changes in aphid’s development, fecundity, survival when introduced to different growth stages, etc. Moreover, natural aphid predators such as the ladybugs are attracted by EBF.

Hence, having our BanAphids produce EBF should help to repel aphids from our plant of choice. In the following sections, we will give you a general background of EBF synthase followed by an overview of the model and the genes, the wetlab work and the biobricks we built for the EBF part. We were also able to characterise these biobricks. We showed that our biobrick has an effect on aphids and used SDS-PAGE to show that it was EBF-synthase was produced. Finally we have made some suggestion how to optimise the production of EBF in the future. For this we will take you on a tour through the pathways that result in EBF and the problems that arise with this. Of course we have added possible solutions to these problems.

We cloned and expressed the EBF synthase gene in E. coli. This enzyme will break down (2E,6E)-farnesyl diphosphate into (E)-β-farnesene (EBF) and diphosphate (see reaction scheme below).

The enzyme prefers bivalent cations as cofactors; a Mg2+ concentration of 5 mM should be beneficial for EBF synthase function. The ideal pH for EBF synthase will be between 5.5 and 7.

The EBF construct we designed consists of a constitutive promoter with a lac operator, the EBF synthase itself and a double terminator. We used BBa_B0015 for the double terminator. EBF is not only made by aphids but also by plants and other organisms in a form of biomimicry. We obtained two different sources of the EBF gene. One gene originates from the soil bacteriumStreptomyces coelicolor (Centre of Microbial and Plant Genetics of KU Leuven). We chose this plant-residing bacterium because it would be a perfect chassis for the ultimate expression of EBF in our E. coligy system. The other EBF gene is from the plant Artemisia annua (sweet wormwood) and was a kind gift from Professor Peter Brodelius (Kalmar University, Sweden). Here we were inspired with the plant origin. The KM for the Artemisia annua protein is calculated at 0.0021 mM, with a Kcat/KM=4.5 and a turnover number of 0.0095 s-1. For the Streptomyces coelicolor protein the KM is 0.0168 mM and the turnover number 0.019 s-1.

Unfortunately, the EBF synthase from Streptomyces coelicolor is a bifunctional enzyme, not only processing β-farnesene but also containing albaflavenone synthase activity. For this reason, we chose to follow up on the Artemisia annua gene and product.

For our construct, our first choice was a medium strength promoter with medium RBS (BBa_K608006); we nonetheless also made the construct with a strong promoter and RBS. The lac operator in front of the EBF synthase gene will allow us to switch the transcription of the EBF synthase gene on and off.

Gettin' the gene

In the case of the EBF synthase gene from Streptomyces coelicolor, we amplified this gene with a colony PCR. The EBF synthase gene from Artemisia annua was received in the pET28 vector from professor Brodelius (Kalmar University, Sweden). In this gene an additional EcoRI restriction site was present, which would conflict with the standard iGEM cloning work. Therefore we removed this site via site directed mutagenesis after transferring the gene into the iGEM pSB1C3 backbone.

Cutting and pasting

Once we obtained the target gene (EBF) in the standard pSB1C3 backbone, we started our cloning work. We used plasmid pSB1C3 with a promoter or terminator as chassis, cut this open and inserted the gene of interest. When ligating the insert in front of the double terminator, we cut the vector with EcoRI and XbaI, and the insert with EcoRI and SpeI. The promotor vector on the other hand is cut with SpeI and PstI restriction sites, and the insert is cut with XbaI and PstI restriction sites. This works because SpeI and XbaI are isoschizomers.

Ligations were performed in parallel in two different ways. In one setup we ligated for 20 minutes at 16 ℃, and in comparison, the second ligation of the same products was conducted at 16 ℃ overnight.

For transformation, we used both chemically competent cells and electrocompetent cells. Electroporation had a higher efficiency when compared to heat shock transformation.

Confirmation

After we observed colonies the next day, we needed to confirm the products. The first step we did was usually a colony PCR to check if the insert was in the vector, this was followed up by digestion confirmation after the plasmid extraction. Only the plasmids which succeeded in both controls were send for sequencing, the final confirmation.

gBlocks

Meanwhile, we also built the EBF construct with a lac operator between the promoter and gene, using the gBlock principle. We designed the gBlocks, assembled them and ligated the insert into pSB1C3 backbone. The colonies obtained also went through the three confirmation steps mentioned above before we were satisfied.

For more details on the labwork and the wetlab difficulties as well as how we overcame them, please consult our wetlab journal.

After we overcame a lot of difficulties, we finally made the following bricks at the end of the summer.

With our EBF synthase constructs ready, we tested them with several aphid experiments.

Our pilot experiment tested the medium strength EBF synthase producing brick BBa_K1060009. We placed aphids on a leaf in the middle of a huge petri dish, an EBF-producing bacterium plate on the left, a control on the right. In the resulting video we observed that the general trend of aphid movement was away from the EBF-producing bacterium. These results suggest our EBF synthase producing bacteria seemed to work.

Moreover, we also tried another set-up with our high strength EBF synthase producing brick BBa_K1060011. This time we connected the leaves that were on the EBF-producing bacteria plate with those on the control plate and with the leaf in the middle where the aphids resided. This facilitates movement of the aphids to other leaves. However, there was no significant difference between the amount of aphids on the control leaves versus the BBa_K106011 leaves. The lac operator in this construct may interfere with the production of significant amounts of EBF.

In addition, we also examined the aphid's behavior without a leaf as a starting point. We put 30 aphids in the middle of a huge petri dish, on the left side we placed a leaf with 10µl of EBF-producing bacteria and on the right side we placed a non-treated leaf as control. Thus, we offered the aphids the chance to go searching for food. After 2 hours we counted the number of aphids on the leaves, there were 4 aphids on the leaf where the EBF was produced and 6 aphids on the control leaf, the rest of aphids just walked randomly in the big petri dish. For lack of time, we could unfortunately not repeat this experiment.

Our pilot experiments indicated a trend in the right direction. Several aspects of the setup can still be optimized in the future, for example the amount of bacteria, the strength of the promoter, the ventilation of the setup, the incubation time and the temperature, etc. The reason for this is that the concentration of EBF is essential to trigger the desired response in the aphids. Both too high and too low concentrations will lead to aphid insensitivity.

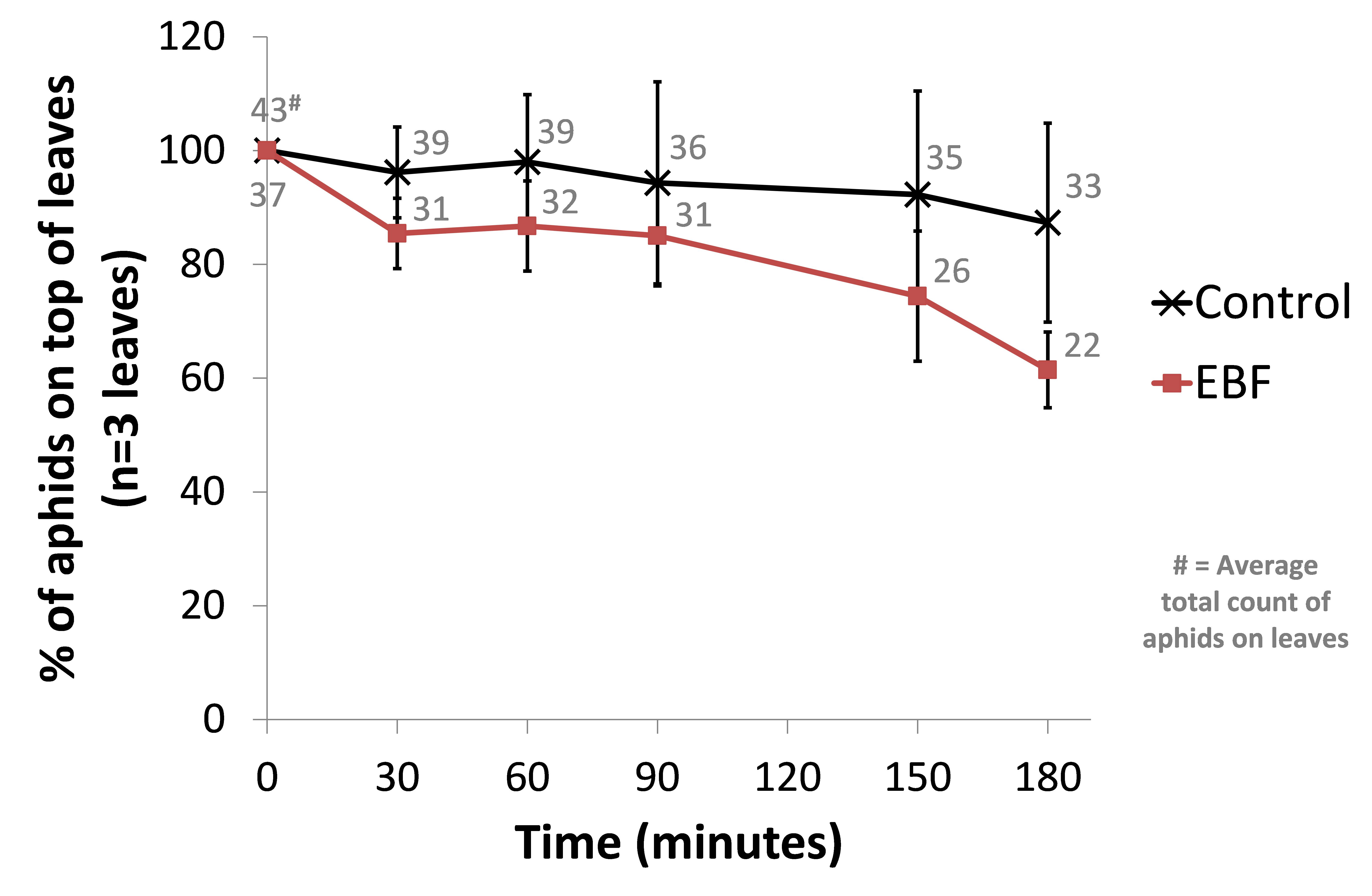

To back-up our pilot experiment, we tested again our medium strength EBF synthase producing brick BBa_K1060009.

This time we used 3 biological repeats for both a control setup (BL21 wild-type) and our EBF producing strain. From an infested Capsicum annuum (‘sweet pepper’ or ‘belt pepper’) plant, leaves from similar sizes were cut and placed it in the glass containers with sufficient natural ventilation. The aphids were then left for one hour before introducing our bacterial plates. Petri dishes with 10µl of a fresh overnight culture (~OD 1.6) were place under each leaf. The amount of aphids on the top side of each leaf were counted and used as a reference point (t=0). Every half hour the aphids were counted in a standardized manner. The amount of aphids moving on each leaf were also counted at each time point. We observed a trend of more aphids scattering away from the leave in the EBF setup but no statistical differences were seen (see Figure 1).

When looking at the percentage of aphids moving at each time point, we observed a similar trend of aphids being more agitated in the EBF setup compared to the control (see Figure 2). This difference was statistacilly significant (P-value = 0.013) at 180 minutes after introducing our bacteria.

Figuur 1: BBa_K1060009 (EBF) or BL21 (control) bacterial plates were placed underneath leaves (n=3) from Capsicum annuum. The amount of aphids on the top side of each leaf were counted at 0, 30, 60, 90, 150 and 180 minutes after the introduction of the bacteria. Data are represented as % of aphids compared to time point 0 ± standard error of mean. The average total count of aphids on the 3 leaves for EBF and control are also shown.

Figuur 2: BBa_K1060009 (EBF) or BL21 (control) bacterial plates were placed underneath leaves (n=3) from Capsicum annuum. The amount of aphids moving around on the top of each leaf were counted at 0, 30, 60, 90, 150 and 180 minutes after the introduction of the bacteria. Data are represented as % of aphids moving compared to the amount of aphids on the top side of each leaf ± standard error of mean. The average total count of aphids moving on the 3 leaves for EBF and control are also shown.

As another approach to prove our constructs (BBa_K1060009, BBa_K1060011 and BBa_K1060014), we transformed our different EBF synthase bricks in an E.coli expression strain, grew these under different temperatures, times and, if possible, IPTG induction levels. Bacterial pellets were harvested and proteins extracted.

Here we show the most interesting results. The figure shows some slight additional bands in lane a (around 110kDa and around 60kDa), the protein extract from the lacI operator medium strength promoter construct. These bands are less clear in the medium and high strength promoter lane. The expected size of the EBF synthase protein is around 66kDa which could fit with the lower band. Gel extraction and Mass Spectrometry based identification will confirm if these bands represent the EBF synthase gene and possibly the increased production of a secondary protein. Interestingly, the lacI medium promoter construct did not influence aphid behaviour. Possibly the expression of EBF synthase is just too high, which would be equally inhibitory as a too low concentration. Other approaches to better identify the functionality of this construct would be via a gas chromatography analysis to directly measure the amounts of EBF produced.

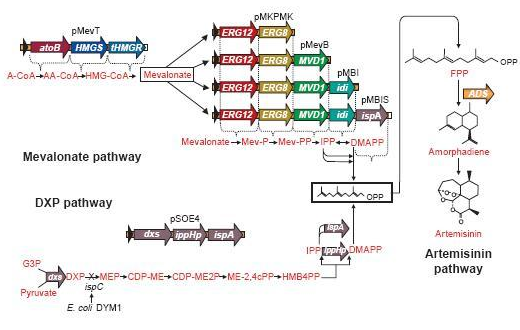

β-farnesene is a terpenoid that is converted from farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) by the enzyme β-farnesene synthase (EC 4.2.3.47).

FPP is the precursor of β-farnesene, that is produced by the building blocks, the molecules isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallylpyrophosphate (DMAPP).

These precursors of farnesyl pyrophosphate can be produced by several metabolic pathways. Most prokaryotes use the non-mevalonate or DXP pathway, producing IPP starting from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and pyruvate. Eukaryotes, except for plants, exclusively use the mevalonate pathway, producing IPP starting from acetyl-CoA. Plants use both pathways.

On the left you can see the non-mevalonate pathway or DXP pathway, showing the conversion of pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to the terpenoid precursor IPP and its isomer DMAPP.

Pyr = pyruvate, G3P = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, DXP = 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, MEP = 2-C-methylerythritol 4-phosphate, CDP-ME = 4-phosphocytidyl-2-C-methylerythritol, CDP-MEP = 4-phosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2-phosphate, MEcPP = 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclopyrophosphate, HMB-PP = (E)-4-Hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate, DXS = DXP synthase, DXR = DXP reductase, CMS = CDP-ME synthase, CMK = CDP-ME kinase, MCS = MEcPP synthase, HDS = HMB-PP synthase, HDR = HMB-PP reductase

FPP is an important precursor, used for the biosynthesis of lots and lots of compounds. Once we insert a plasmid containing the β-farnesene synthase gene, we may obtain only a very small amount of β-farnesene, since the precursor amount wasn't increased and there simply isn’t enough FPP available to produce the amount of β-farnesene to fully use the capacity of the EBF synthase enzyme we brought in.

A solution may be to co-transform plasmids to engineer a mevalonate pathway in E. coli, thereby upregulating the production of FPP. This larger amount of FPP may then be converted to β-farnesene, creating a large enough amount of this volatile. This was demonstrated many times by J.D. Keasling in S. cerervisiae, while Martin et al., (2003) implemented this mevalonate pathway in E. coli. In the article, they described their successful efforts to create a high level production of amorphadiene by introducing the mevalonate pathway in E. coli. However, expression of this heterologous pathway led to such an abundance of isoprenoid precursors that cells ceased to grow or mutated to overcome the toxicity. This once again shows the need for a controlled production of the elements in this pathway; too much is equally detrimental as too little.

Since there are eight genes responsible for the mevalonate pathway, Martin et al. decided to split them up into two parts. A first plasmid named pMevT, responsible for the conversion of acetyl-CoA to mevalonate, harboring the atoB, HMGS and tHMGR genes into a pBAD33 vector, and a second one named pMBIS, harboring the ERG12, ERG8, MVD1, idi and ispA genes into a pBBR1MCS-3 plasmid. Coexpression of these two operons in an ispC deficient E. coli strain produced the terpenes, even in the absence of mevalonate, indicating that the mevalonate pathway works. A combined expression of their recombinant mevalonate pathway and the synthetic gene product (ADS in their case) resulted in greatly improved yields.

Even though we do not need a very high production of EBF it would be definitely better to optimise the pathway, by using the plasmids pMevT and pMBIS, described above. Implementing them into our BanAphids along with the synthetic β-farnesene synthase gene could result into high yields of β-farnesene. This way the amount of EBF can be easily changed via the amount of bacteria used or the concentration of the cofactor Mg2+.

Due to the short amount of time iGEM offered we did not yet started doing this, but this is definitely something future teams might look into.

Kajiwara S., Fraser P., Kondo K., Misawa N., Expression of an exogenous isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase gene enhances isoprenoid synthesis in Escherichia coli, Biochem J. 324, 421-426 (1997).

Martin V., Pitera D., Withers S., Newman J., Keasling J., Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids, Nature Biotechnology 21(7), 796-802 (2003).

"

"