Team:Manchester/KnowledgeDeficit

From 2013.igem.org

Introduction

It is widely believed that there is a lot of hostility between scientific and non scientific communities (often generalised under the term “the public”). In some cases this is true. One only has to look at the Monsanto-driven GM food crisis of the late 20th and early 21st centuries to see the effects large biotechnology companies can have on developing countries, and the tension this can cause. But where does the public truly stand on issues of science, in particular synthetic biology? Is there is a division of opinion between scientists and non-scientists; why is it there, and how should scientists approach this issue?

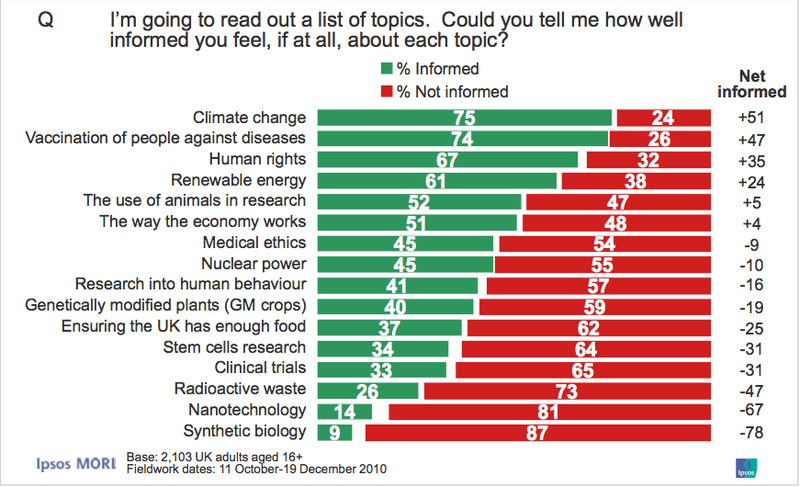

On first inspection, the current level of support for synthetic biology is looking poor. A 2011 study carried out by the UK Government Department for Business and Skills showed that just 8% of the British public felt informed about synthetic biology (the results in full can be seen below)[1]. You could be forgiven for thinking that synthetic biology is a PR disaster waiting to happen: an ethical minefield that scientists can’t help the public traverse. However, let us not jump to conclusions. Of the modest portion of Brits who said they had heard of synthetic biology, a third believed the benefits of synthetic biology would outweigh the risk, 12% thought the opposite, and the remaining 55% were unsure.

A modest start then, but still a long way to go in terms of mass public acceptance. In order for scientists to get the public to strongly support synthetic biology, a careful approach must be taken in regards to science communication. One very important factor to consider is the knowledge deficit assumption.

The knowledge deficit assumption is the concept that the public won't accept new technologies because they do not have sufficient fundamental scientific knowledge to understand them[2]. If somebody does not accept a new technology or idea, it must therefore be because they do not know science. It produces a linear model of acceptance, suggesting that more teaching leads to more acceptance. This model is flawed on two main levels:

Issue 1: The Sheep and the Goats

The knowledge deficit assumption establishes two distinct groups of ‘expert’ and ‘non-expert’. This leads to the idea that if scientists are experts and the public is not, so only the opinion of the scientist is a valid one. Of course, a scientist who has spent years working on a project is going to have an in depth knowledge in their field of study, there is no doubt about that. However this expertise can give a very narrow scope when looking at the bigger picture. A researcher can spend a lot of time agonising over each tiny detail of their project; such as product yield, kill switches or containment. What they may not consider are some of the social implications that the public would raise.

An example of this comes from a case study carried out in Mexico in 2004[2][3]. The study was investigating the effects of a recent cross-contamination between Monsanto-brand transgenic maize grown in the USA and native maize growing in Mexico. This was a major issue as Mexico is the main source of all genetic diversity of maize crops, with a population that gets 80% from its nutrition from maize products. GM maize was already banned by the Mexican government, so this cross-contamination was a serious concern. A study was carried out by the Commission on Environmental Cooperation (CEC). At a meeting between the scientists and the local campesinos, the scientists presented lots of technical data in an attempt to reassure the locals that there is no reason to be concerned. There was no evidence of any adverse effects on the maize, and no reason to suggest that the problem would escalate. However, despite solid scientific backing, their attempt to calm the locals felt unconvinced. Mexico has been cultivating maize for over 6000 years[4], and so it is deeply ingrained within Mexican culture. The campesinos gave passionate speeches, fearing a change in their livelihood and their future. The scientists, acting in the way the knowledge deficit model would suggest, thought that the locals had just simply misunderstood what they were saying. The issue was not that the public had ignored the science. The issue was that the scientists had ignored the concerns the locals actually had. This leads to the second major issue with the knowledge deficit assumption:

Issue 2: Knowledge Doesn’t Necessarily Equal Power

As highlighted in the previous example, an audience hostile to what you have to say isn’t going to necessarily be on your side after simply explaining the technical facts. Anecdotally, this makes sense. You can explain to someone who’s arachnophobic that the spider they’re running away from is completely non-venomous, or how it has no reason or ability to harm them, but they’re still going to be afraid of the spider. In a similar vein, the campesinos who feared their livelihoods would be ruined were still fearful after they were presented with the evidence.

Of course, one cannot make a valid claim on anecdotal evidence alone, There are some slightly more empirical data to back this point up, coming from a British House Of Lords report carried out in the year 2000[5]. In this report, the results of a survey carried out by Sir Robert May in the early 90s are discussed. He found that European countries with a deeper level of understanding of the scientific method, such as the UK and Denmark, were not as instantly enthusiastic or supportive of some aspects of science compared to other countries where scientific education was of a lower standard. A similar American study carried out in 2004 [6] found that although 63% of people never discuss GM food and 44% of people hadn’t really heard much about it, only 23% of people were actually against the concept of GM plants. The fact that the GM food industry is growing in the US, whereas the EU has a tight grip on GM with stringent regulation shows that this is still the case. In essence, an informed public may use the information given to conclude they are not comfortable with potential risks[7]

Knowledge Deficit In Practice: Industry and the Public

Few in the field can deny that synthetic biology is going to grow, thrive and have a great impact on society. It is therefore imperative that the public is comfortable with the new technologies that will have an effect on them. Synthetic biology promises a sustainable future, with countless possibilities, and preventing its growth would truly be a shame. Given the fact that the possibilities will be put in action by industry, it is important that they present a good image of SynBio. As previously discussed, however, telling the public facts isn’t going to make them accept synthetic biology (unless they’re already supporters). So what can be done? To find out, the team contacted members of three large biotechnological companies; in addition to small business and local environmentalists. We discussed a range of topics: the direction synthetic biology is heading, how this will impact society, how we can control the impact, and why there may be public mistrust in industry.

The Industry

The talks with industry revealed a number of recurring themes, but also a few interesting divisions of opinion. Each industry agreed that research done in universities is trusted more than research done by industry. They shared the opinion that university research is seen as more philanthropic, being driven by the desire for knowledge and the good of humanity. In contrast, industry is seen as being seen as profit-driven, and science is driven by the will of the shareholder. So how do we circumvent this issue? Two of the companies went along the lines of educating the public, claiming the public are uninformed on issues of synthetic biology. Fortunately, they both appreciated that this may not be effective. There will always be fear, anticipation or surprises in emerging technologies, even amongst scientists. Right now, synthetic biology doesn’t have much to show for itself in everyday life, but the two companies agreed that having a concrete product that the public can see the benefits of will help convince the product round to ‘our’ way of thinking.

The final company believed that the two main problems come from distrust of monopoly and distrust of business practices. These two issues are very distinct, but are often fused together to create a ‘big scary biotechnology’ image. This has implications: tighter regulations (to try and improve business practices) and less funding (to halt monopolies) are both acting in a vicious cycle. It is becoming more difficult for startup companies to get the funding, and because there are so many rules, it is actually creating a worse monopolistic culture.

The Public

After speaking with industry, we wanted to see how the public really feel about synthetic biology so the team visited a local environmentalist group. Perhaps surprisingly, there was very little hostility to the concept of synthetic biology. The usual hostile comments about ‘playing with nature’ were absent. Instead, the most prominent area of discussion was based around ownership and usage. How will the products be regulated? Is is morally right that some people can benefit from synthetic biology, but others cannot? (Incidentally, these points have influenced us during the rest of the human practices side of our project. You can read more about it here )

So what do the public want? The public something more than simply ‘communication’. They want a two-way dialogue. Scientists educating the public about their research can increase the scientific knowledge of non-scientists, but scientists also need to appreciate the concern of the public. As addressed previously in issue 1, dividing the public in to ‘experts’ and ‘non-experts’ is going to hinder discussion, widening the gap between the two groups of people. The environmentalists we spoke to said they would like to see more debates, more often. The industries agreed to some extent, highlighting the need for large public consultations including people from a wide range of backgrounds; scientists and non-scientists alike. It was stated that iGEM is a great force for science communication, as it gives the public something they can relate to (it’s much easier to talk to some undergrad students than a large faceless organisation).

Manchester was a large part of the industrial revolution in the 19th Century. We hope for it to play a large part in the next, great industrial revolution. It is imperative that scientists, both academic and industrial, engage with the public and encourage open dialogue to ensure it can reach its full potential as we have done during the course of our project.

References

(1) http://www.ipsos-mori.com/Assets/Docs/Polls/sri-pas-2011-summary-report.pdf

(2) http://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/92654

(3) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC523889/

(4) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC29388/

(5) http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199900/ldselect/ldsctech/38/3801.htm

(6) http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/18175/1/rr040007.pdf

(7)http://www.sciencewise-erc.org.uk/cms/listening-or-explaining-avoiding-a-deficit-approach-to-public-engagement-in-synthetic-biology/

(8) We would like to thank all of the representatives of companies and organisations who gave up their time to speak to us about these issues

"

"