Team:Newcastle/Project

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

[[File:SyntheticBiologyEngineeringLifeCycle.jpg|500px|center]] | [[File:SyntheticBiologyEngineeringLifeCycle.jpg|500px|center]] | ||

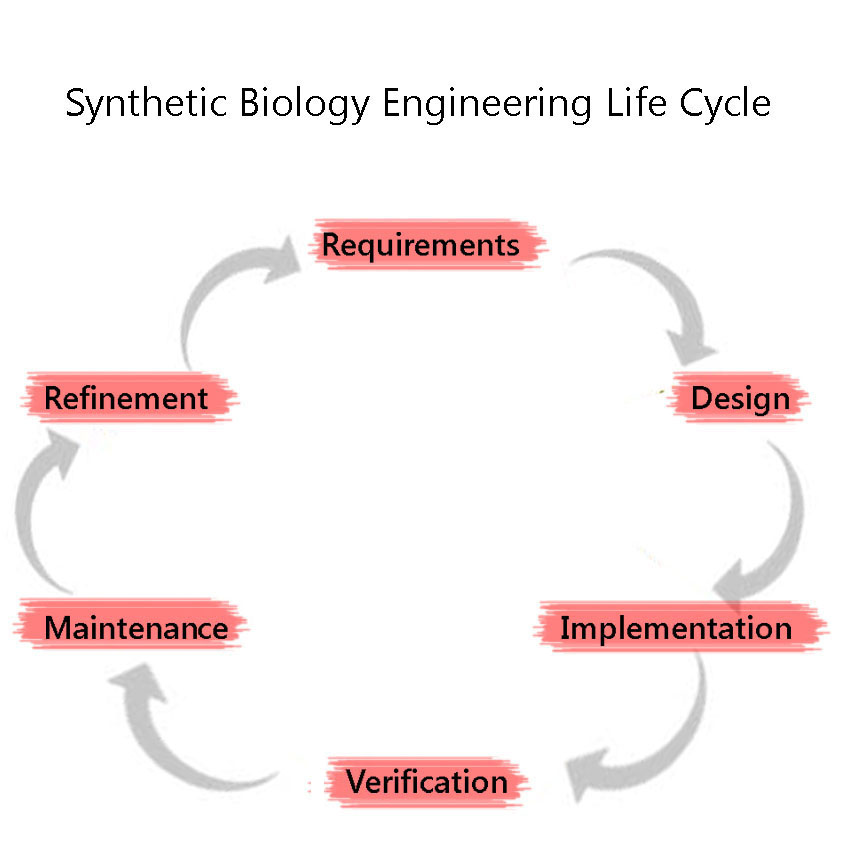

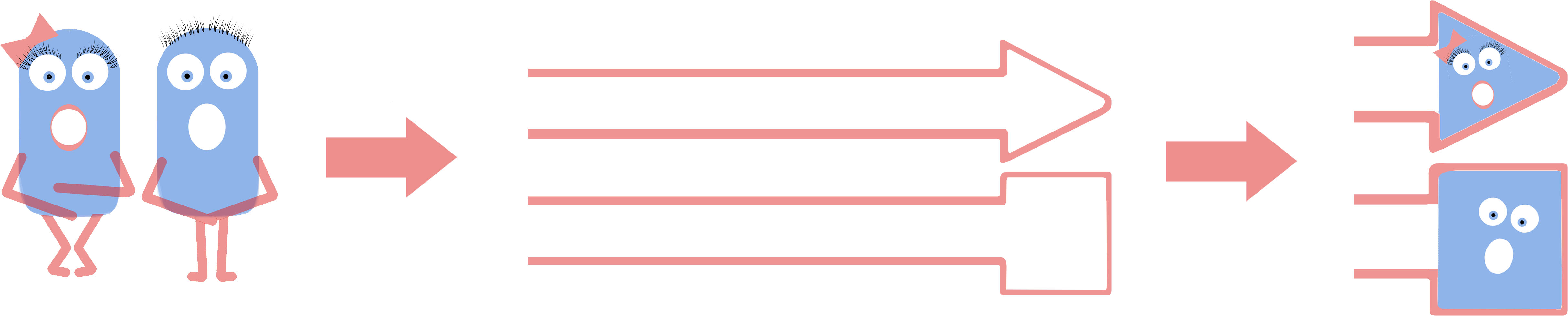

| - | Synthetic Biology is a discipline which heavily employs engineering principles. One of these principles is the Engineering Lifecycle, a framework in which the project is split into clearly defined sections, based on the development of the project. These are, in sequential order: 1) Requirements 2) Design (including Modelling) 3) Implementation 4) Verification 5) Maintenance 6)Refinement and the cycle is iterated through again, as we attempt to improve the system further. We adhered to this cycle throughout our project including the development and | + | Synthetic Biology is a discipline which heavily employs engineering principles. One of these principles is the Engineering Lifecycle, a framework in which the project is split into clearly defined sections, based on the development of the project. These are, in sequential order: 1) Requirements 2) Design (including Modelling) 3) Implementation 4) Verification 5) Maintenance 6)Refinement and the cycle is iterated through again, as we attempt to improve the system further. We adhered to this cycle throughout our project including the development and characterization of our BioBricks. This included modelling our BioBricks and sub-project outcomes before any experiments were conducted. This helped us better understand our engineered systems and predict the results of our ‘wet’ lab experiments. |

| - | Click on the links below to view each model or visit our modelling page | + | Click on the links below to view each model or visit our [https://2013.igem.org/Team:Newcastle/Modelling/Introduction introductory modelling page]: |

*[https://2013.igem.org/Team:Newcastle/Modelling/L-form_Switch L-form switch] | *[https://2013.igem.org/Team:Newcastle/Modelling/L-form_Switch L-form switch] | ||

*[https://2013.igem.org/Team:Newcastle/Modelling/CellShapeModel Cell Shape] | *[https://2013.igem.org/Team:Newcastle/Modelling/CellShapeModel Cell Shape] | ||

Revision as of 21:53, 4 October 2013

Contents |

Project Overview

Synthetic Biology is a discipline which heavily employs engineering principles. One of these principles is the Engineering Lifecycle, a framework in which the project is split into clearly defined sections, based on the development of the project. These are, in sequential order: 1) Requirements 2) Design (including Modelling) 3) Implementation 4) Verification 5) Maintenance 6)Refinement and the cycle is iterated through again, as we attempt to improve the system further. We adhered to this cycle throughout our project including the development and characterization of our BioBricks. This included modelling our BioBricks and sub-project outcomes before any experiments were conducted. This helped us better understand our engineered systems and predict the results of our ‘wet’ lab experiments.

Click on the links below to view each model or visit our introductory modelling page:

A Foundational Advance

While researching Synthetic Biology we found that a cell wall, one of the standard components of the bacterial cell, often causes difficulties in many techniques. These included transformation efficiency, secretion of recombinant proteins, adaption to the environment etc. So we thought to ourselves: is there any way to remove the cell wall and still have a viable cell?

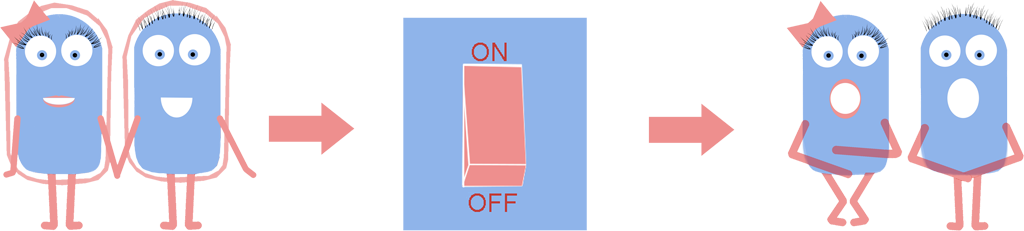

As a result we have developed a new chassis with the potential to revolutionise how Synthetic Biology is performed. The main BioBrick(BBa_K1185000) that we have introduced enables the switching on and off of the bacterial cell wall in the model Gram positive bacteria Bacillus subtilis, at the demand of the synthetic biologist, while still allowing cells to grow and divide. Employing bacterial cells without a cell wall can both enable the synthetic biologist to explore new applications and research areas, and also build-upon and improve areas that are already being explored in Synthetic Biology. Rather than the application-oriented nature of many iGEM projects, we think that the use of cell wall-less bacteria as a novel chassis in Synthetic Biology, as we propose, can benefit across the whole subject area, and furthermore be utilised as a tool to allow for even greater feats to be achieved by future iGEM teams.

Bacteria which have lost their cell wall yet are still able to grow and divide are called L-forms, or as we prefer to call them, naked bacteria. If you would like to learn more about L-forms, please take a look at our L-form page or click here to watch a short video summarising our project.

Once we had created L-forms with our Switch BioBrick, we were unable to ignore the new opportunities that L-forms bring to Synthetic Biology:

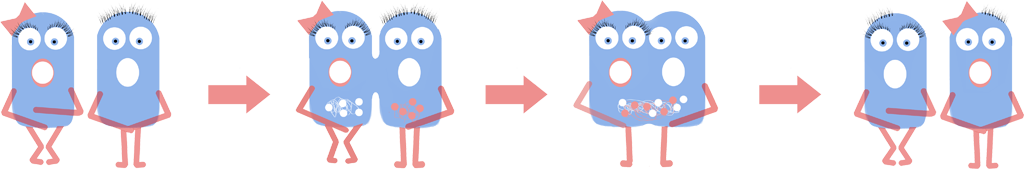

Genome Shuffling

We investigated using genome shuffling and L-forms to artificially evolve B. subtilis. Genome shuffling increases the rate of evolution, allowing the improvement of any biological system or phenotype in a feasible time frame. Over the past eight years iGEM teams have dreamt up innovative ways of harnessing Synthetic Biology. However this relatively new field faces challenges such as producing high quality yield of the desired product. Using L-forms allows the use of genome shuffling to solve this problem. If harnessed this could improve the efficiency of hundreds of iGEM projects as well as cell factories across the field of synthetic biology.

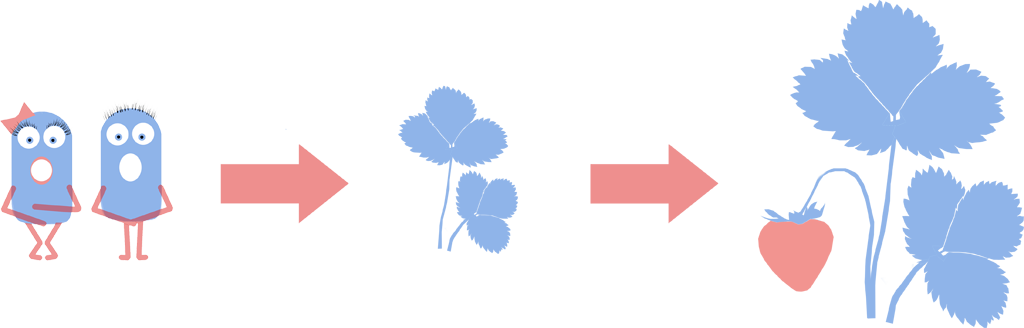

Introduction and Detection of Naked Bacteria in Plants

We successfully inoculated HBsu-GFP tagged L-forms into Brassica pekinens (Chinese cabbage). L-forms have been shown to form symbiotic relationships in plants such as Chinese cabbage and strawberries. Plants with naked bacteria show increased resistance to fungus and L-forms could be engineered to deliver useful compounds to crops; an artificial symbiotic relationship. In the future L-forms could be engineered to provide their host plants with beneficial compounds such as nitrogen, plant hormones or antifungals. This could give better crop yields, more nutritious harvests and reduce the need for spraying of fertiliser, pesticides or other compounds. Crucially, we have shown that L-forms will burst if they are not in an osmotically stable environment. This makes them a better delivery system than cell walled bacteria as they will die if they exit their host plant.

Shape Shifting

The loss of the cell wall leaves L-forms protected by only a cell membrane. The plasma membrane of L-forms is quite fluid. The advantage of this is that these cells would be able to adapt to shapes of various cracks and cavities, or will be able to "squeeze through" tiny channels and deliver cargo to hard-to reach targets.

This isn’t a finite list of what can be done with naked bacteria, there’s loads more! L-forms are currently used to discover novel antibiotics which don’t act on the cell wall. L-forms can also teach us a great deal about how bacterial life has evolved, through acting as a model for a cell wall-less bacterial progenitor, and through being able to test the ease of induction of endosymbiosis in cell wall-less organisms (Mercier et al. 2013).

In addition to our work above, we characterized Part: BBa_K818000 showing that it does not work in B. Subtilis. We then sequenced this part, noted that its sequence differed from its entry on the iGEM registry and created a new registry page for Part: BBa_K1185004 with the correct sequence.

Modelling

For every research theme we have constructed a model to help us understand the systems we engineered. Click on the links to view each model or visit our modelling page:

References

"

"