Team:UNITN-Trento/Project/Methyl Salicylate

From 2013.igem.org

Cridelbianco (Talk | contribs) |

Cridelbianco (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

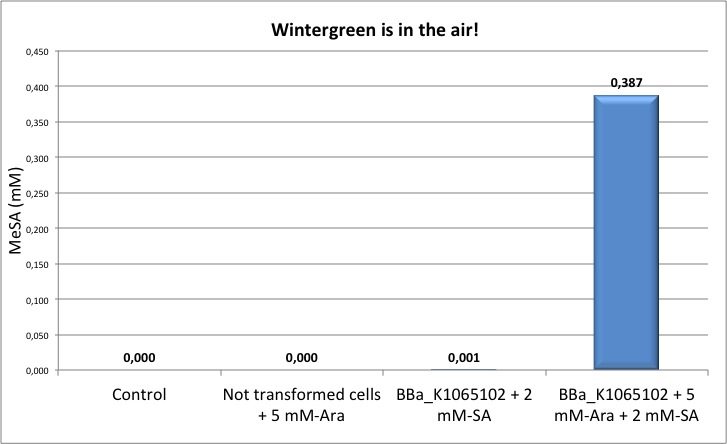

| - | Our MeSA device <a href="">BBa_K1065102</a> was able to produce a significant concentration of MeSA only in the presence of salycilic acid. This finding was also previously observed by the MIT team in 2006 with their device XX. This result was initially imputed to the lack of SAM synthetase. However, after we received the DNA sequencing results of the MIT part (xx) and of our complete device (built with MIT parts) we realised that the pLAC promoter was missing the -35 box, thus generating a less strong promoter. We believe that this problem can significantly affect the correct functioning of the device. We are now in the process of improving this part by mutagenesis to | + | Our MeSA device <a href="">BBa_K1065102</a> was able to produce a significant concentration of MeSA only in the presence of salycilic acid. This finding was also previously observed by the MIT team in 2006 with their device XX. This result was initially imputed to the lack of SAM synthetase. However, after we received the DNA sequencing results of the MIT part (xx) and of our complete device (built with MIT parts) we realised that the pLAC promoter was missing the -35 box, thus generating a less strong promoter. We believe that this problem can significantly affect the correct functioning of the device. We are now in the process of improving this part by mutagenesis to rebuild a full functional pLAC promoter. |

Revision as of 20:29, 30 September 2013

B. fruity needed also a fruit ripening ihnibitor. It was difficult to find a volatile molecule that could be enzymatically produced by a bacteria and also proofed to be an efficient ripening inhbitor. There were not many candidates to choose from and after a long search we found methyl salicylate (MeSA). Previous work suggested that MeSA inhibits the ripening of kiwifruit (Aghdam M. et al., Journal of Agricultural Science. June 2011, Vol. 3, 2, pp. 149-156) and tomatoes, at a concentration of 0.5 mM (Ding, C. and Wang, Plant Science 2003, Y. 164 pp. 589-596).

We were happy to find out that many of the needed parts to produce MeSA were already available in the registry. These parts were initally built by the MIT 2006 iGEM team for the project Eau de coli.

Figure 1: In this picture is shown the pathway that was exploited to produce Methyl Salicyalte. The precursor is the chorismate, a metabolic intermediate of the Shikimate pathway which many plants and bacteria (like E.coli and B.subtilis ) have. The chorismate undergoes firstly a reaction of isomerization by the isochorismate synthase, PchA and then the salicylate is obtained by the action of PchB an isochorismate pyruvate lyase. Both enzymes are from the micro-organism Pseudomonas aeruginosa . In the final part of the reaction, BSMT1, a methyltransferase, transfer a methyl group from the S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthesized by the SAM synthetase.

Figure 1: In this picture is shown the pathway that was exploited to produce Methyl Salicyalte. The precursor is the chorismate, a metabolic intermediate of the Shikimate pathway which many plants and bacteria (like E.coli and B.subtilis ) have. The chorismate undergoes firstly a reaction of isomerization by the isochorismate synthase, PchA and then the salicylate is obtained by the action of PchB an isochorismate pyruvate lyase. Both enzymes are from the micro-organism Pseudomonas aeruginosa . In the final part of the reaction, BSMT1, a methyltransferase, transfer a methyl group from the S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthesized by the SAM synthetase.

We modified and improved these parts and resubmitted them to the registry. For example, we substituted the pTet promoter controlling the BSMT1 enzyme with an araC-pBAD promoter. Additionally the MIT team did not include in their MeSA generator device the enzyme SAM synthetase, that we hope will boost MeSA production. We also have re-submitted in pSB1C3 the single enzymes of the pathway.

MeSA detection

MeSA detection

MeSA is an highly volatile liquid with a distinct minty fragrance. We exploited the physical properties of MeSA to quantify its production by gas chromatography using a Finnigan Trace GC ULTRA connected to a flame ionization detector (FID). This kind of instrument, is able to detect ions formed during MeSA combustion in a hydrogen flame. The generation of this ions is proportional to MeSA concentration in the sample stream. A calibration curve was initially created using samples with a well known pure MeSA concentration (0 mM, 0.2 mM, 0.5 mM, 1.0 mM, 2 mM).

NEB10β cells transformed with BBa_K1065102 were grown in M9 medium, induced with 5 mM arabinose and in some cases supplemented with salicylic acid. All the gas chromatography measures here reported were done in liquid phase, by injecting 1 ul of pre-filtered culture in the instrument. Figure 3: induced sample produces MeSA. A culture of cells transformed with BBa_K1065102 was grown until O.D. 0.6 was reached. The culture was then splitted in 2 samples and one was induced with 5 mM arabinose. 2 mM salycilic acid was added to these samples. After about 4 h the samples were connected to the Gas Chromatograph. The induced sample (blue trace) shows the characteristic peak of methyl salicylate, as opposed to non induced cells (red trace).

Figure 3: induced sample produces MeSA. A culture of cells transformed with BBa_K1065102 was grown until O.D. 0.6 was reached. The culture was then splitted in 2 samples and one was induced with 5 mM arabinose. 2 mM salycilic acid was added to these samples. After about 4 h the samples were connected to the Gas Chromatograph. The induced sample (blue trace) shows the characteristic peak of methyl salicylate, as opposed to non induced cells (red trace).

"

"