DAC Team

Introduction

In order to find new antibacterial compounds, we focused on the signaling molecule bis-(3’,5’)-cyclic dimeric adenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP) as it has proven to be an essential second messenger in many pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria (Witte et al., 2008). It was reported to have a crucial functions in cell wall synthesis and spore formation in Bacillus subtilis (Oppenheimer-Shaanan et al., 2011; Mehne et al., 2013). Interestingly, both absence and excess of c-di-AMP have detrimental effects on cell growth and morphology (Luo and Helmann, 2012; Mehne et al., 2013).

Knowing this information it makes sense that we take a closer look at the enzyme, the diadenylate cyclase, which produces c-di-AMP.

The cyclase domain is conserved among several Gram-positive bacteria like B. subtilis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes (Corrigan and Gründling, 2013). So far, the diadenylate cyclase DisA from B. subtilis has been purified (Witte et al., 2008). However, the purification and crystallization of DisA comes along with some difficulties so we decided to concentrate on the diadenylate cyclase in L. monocytogenes, DacA.

Results and Discussion

As the cloning of the full-length (273 aa) membrane-bound DacA (Lmo2120) into Escherichia coli failed, we excluded the trans-membrane domains meaning we chopped off the first 100 amino acids. Nevertheless, the resulting truncated part still included the essential cyclase domain, and therefore represents one of our favorite BioBricks: [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1045003 BBa_K1045003]!

As the cloning of the full-length (273 aa) membrane-bound DacA (Lmo2120) into Escherichia coli failed, we excluded the trans-membrane domains meaning we chopped off the first 100 amino acids. Nevertheless, the resulting truncated part still included the essential cyclase domain, and therefore represents one of our favorite BioBricks: [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1045003 BBa_K1045003]!

Conducting several experiments we proved that the truncated DacA protein ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1045003 BBa_K1045003]) was not only active in vivo, but also in vitro. Moreover, we were able to purify the diadenylate cyclase in large scale for determining its protein structure! One can now further search for chemical compounds that interfere with the activity of the cyclase by computational modeling.

Following, the experiments will be explained in more detail. However, if you wish to get even more details, please visit the Parts Registry or our LabBook.

The truncated DacA protein ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1045003 BBa_K1045003]) was extended with an N-terminal Strep-tag allowing easy purification steps. Moreover, this construct was brought under the control of a T7-promoter enabling us to induce the expression by addition of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranosid (IPTG). The E. coli strain BL21 was then transformed with this construct. (The Gram-negative bacterium E. coli does not produce c-di-AMP and is not severely affected by the signaling molecule in contrast to Gram-positive bacteria.)

In order to analyze the cyclase activity in vivo, the E. coli clones were induced to express the protein by the addition of IPTG. The cells were then lysed to extract c-di-AMP from the cells.

By performing SDS gel electrophoresis it was nicely shown that the desired protein was highly expressed (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the presence of c-di-AMP in the supernatant of the lysed bacteria was confirmed using LC-MS/MS. Thus, one can conclude that our truncated DacA protein codes for an active adenylate cyclase domain in vivo.

Fig. 1. Confirmation of the high expression of DacA. The SDS gel electrophoresis confirmed the high expression of DacA Lmo2120 in three biological replicates showing a thick band at about 20 kDa; Lane 1: Thermo Scientific Page Ruler Plus Prestained Protein Ladder.

Diadenylate cyclases catalyze the condensation reaction of two molecules ATP to a single molecule c-di-AMP while releasing two pyrophosphate molecules consisting of the β-γ-phosphates of each ATP (Fig. 2). In order to analyze the cyclase activity of DacA in vitro, we performed an assay in which these pyrophosphate molecules were used as evidence for the reaction. Among other things, the assay included a pyrophosphatase that cleaves the pyrophosphate molecule in free phosphate molecules, malachite-green and molybdate. Malachite-green forms a complex with free phosphate molecules and molybdate that can be measured due to its absorption spectrum. With this in vitro assay the concentration of free phosphate molecules and thus the conversion rate of ATP to c-di-AMP was analyzed.

Our results confirmed that DacA Lmo2120 acts as an active enzyme in the presence of a divalent cation, ATP and a buffer system at pH 8 (in vitro), however, the catalysis rate in vivo seems to be much more efficient.

Fig. 2. Cyclic di-AMP production and degradation. Cyclic di-AMP is produced from two molecules of ATP by diadenylyl cyclase (DAC) enzymes and degraded to pApA by phosphodiasterases. (Edited from Corrigan and Gründling, 2013)

Finally, we are coming to the core of our project, the protein structure of DacA! The molecular structure of DacA can lead to the discovery of new antibacterial substance classes in silico, which later can be used to treat patients.

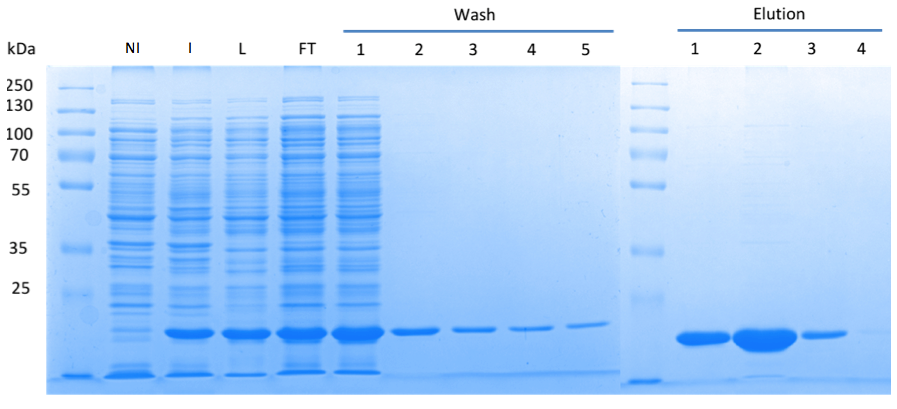

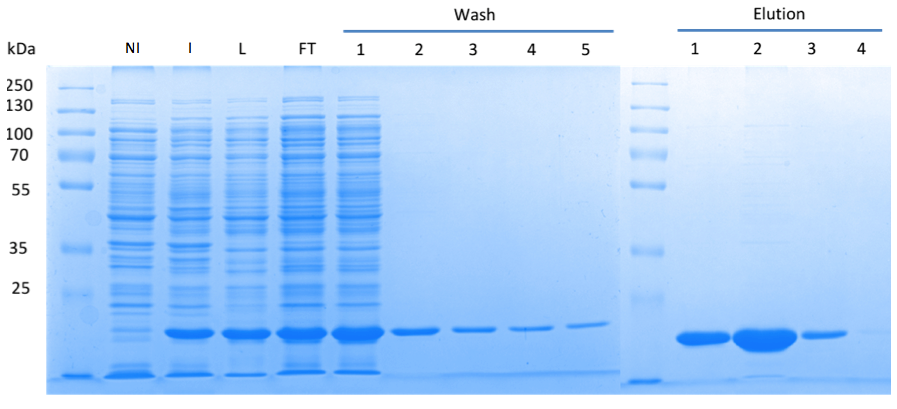

In order to purify a large amount of this protein, our BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K1045003 BBa_K1045003] with an N-terminal Strep-tag was expressed in E. coli under the control of a T7-promoter. The expression was again induced by supplementing the growth medium with IPTG. The high expression was confirmed by SDS gel electrophoresis with a resulting thick band at the size of 20 kDa (Fig. 3). The E. coli strain was grown in large scale with the result that 10 l of cell cultures were lysed and purified (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. SDS gel showing overexpression and purification of DacA. (A) Lane 1: Thermo Scientific PageRuler Plus Prestained Protein Ladder; NI: Non-induced, Clone contained the cyclase domain of which the activity was not induced; I: Induced, Clone contained the cyclase domain of which the activity was induced by addition of isopropyl-ß-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG); L: Lysate; FT: Flow-through; After wash 1 our protein was purified.

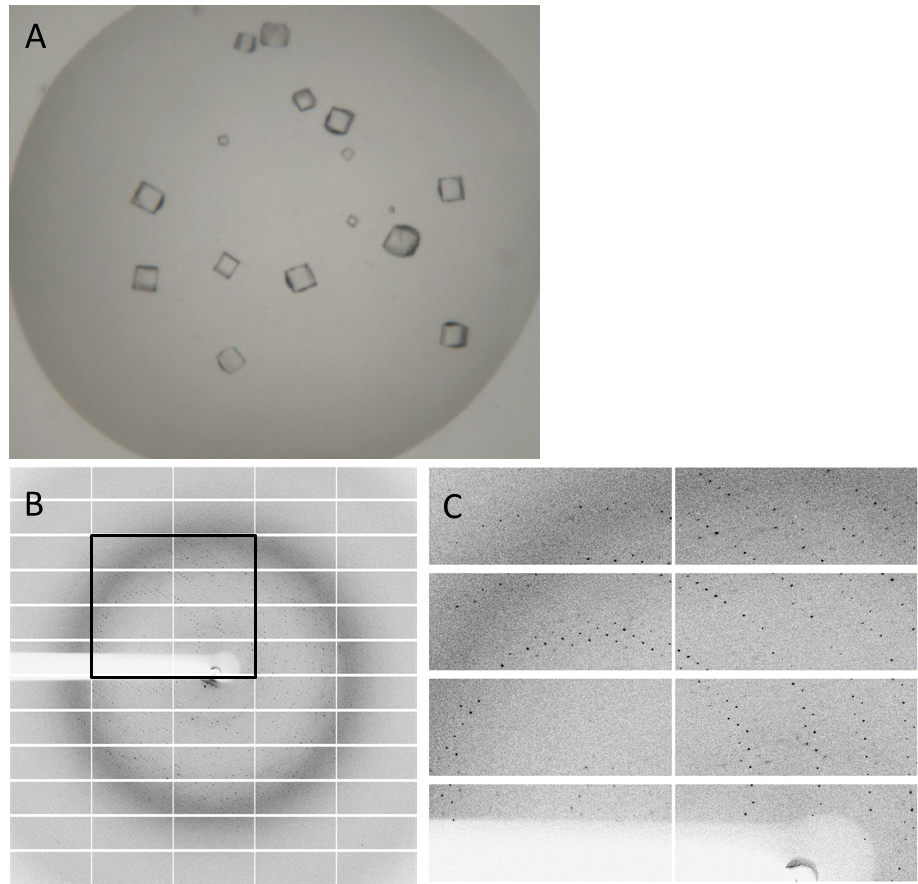

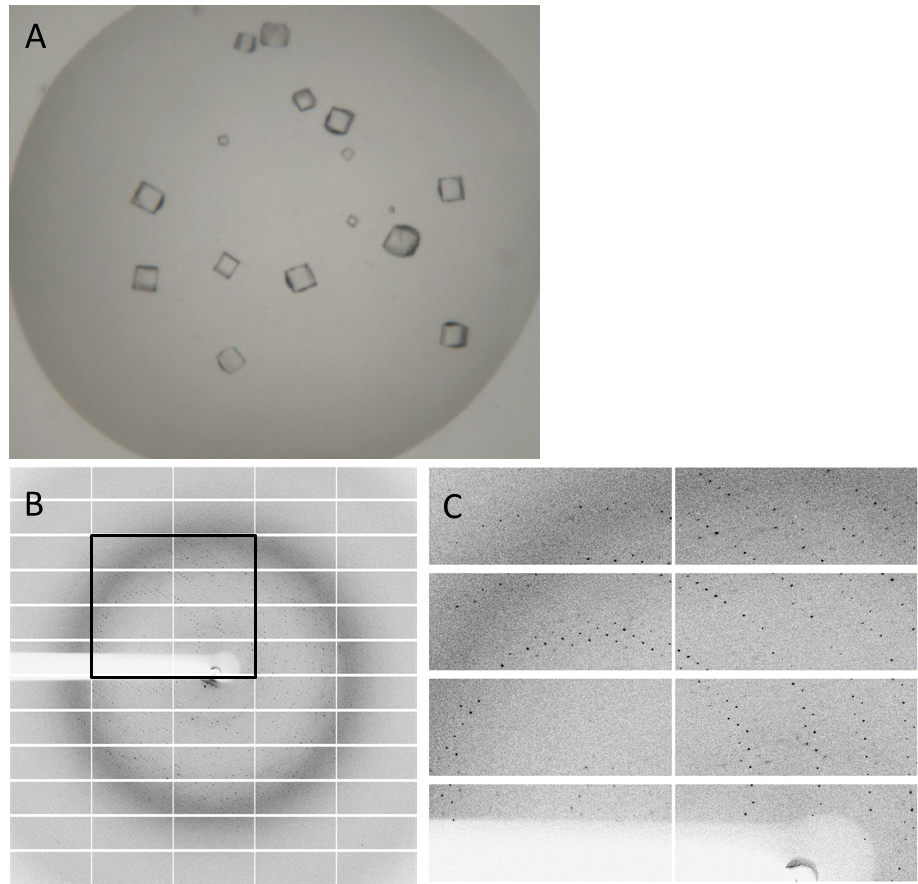

Having dialyzed and concentrated the eluted protein, we obtained a protein concentration of 10 mg/ml, which was sufficient to perform the crystallization reaction. Very nice crystals were already received in a trial when testing different conditions (Fig. 4A). In order to find the perfect supplements for growing our crystals, the whole procedure was repeated. The crystal yields an x-ray diffraction pattern with a resolution of 2,8 Å (Fig. 4B,C). The dataset was measured at the EMBL Hamburg Beamline P13 at the PETRA III synchrotron on the DESY campus.

Finally, we were also able to obtain the protein structure (Fig. 5)! The structure shows a globular protein with a distinct ATP-binding cleft. The ribbon model demonstrates the general structure composed of α-helices and β-sheets.

Fig. 4. Crystals and diffraction pattern. Nice crystals were received with a medium concentration of alcohol and other supplements (A). X-ray diffraction image of DacA (Lmo2120) crystals (B); the highlighted box is shown enlarged (C). The dataset was measured at the EMBL Hamburg Beamline P13 at the PETRA III synchrotron on the DESY campus.

Fig. 6. Protein structure of DacA. (A, B) Ribbon representation of DacA in the ATP bound state. (C, D) Surface structure of DacA and the ATP-binding pocket. (E) Magnified view into the ATP-binding pocket

References

Corrigan RM and Gründling A. (2013) Cyclic di-AMP: another second messenger enters the fray. Nat Rev Microbiol. 11(8):513-524

Luo Y and Helmann JD. (2012) Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis σ(M) in β-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol Microbiol. 83(3):623-639

Mehne FM, Gunka K, Eilers H, Herzberg C, Kaever V, Stülke J. (2013) Cyclic di-AMP homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis: both lack and high level accumulation of the nucleotide are detrimental for cell growth. J Biol Chem. 288(3):2004-2017

Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Wexselblatt E, Katzenhendler J, Yavin E, Ben-Yehuda S. (2011) c-di-AMP reports DNA integrity during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO Rep. 12(6):594-601

Witte G, Hartung S, Büttner K, Hopfner KP. (2008) Structural biochemistry of a bacterial checkpoint protein reveals diadenylate cyclase activity regulated by DNA recombination intermediates. Mol Cell. 30(2):167-178

Previous

Next

"

"

As the cloning of the full-length (273 aa) membrane-bound DacA (Lmo2120) into Escherichia coli failed, we excluded the trans-membrane domains meaning we chopped off the first 100 amino acids. Nevertheless, the resulting truncated part still included the essential cyclase domain, and therefore represents one of our favorite BioBricks: [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1045003 BBa_K1045003]!

As the cloning of the full-length (273 aa) membrane-bound DacA (Lmo2120) into Escherichia coli failed, we excluded the trans-membrane domains meaning we chopped off the first 100 amino acids. Nevertheless, the resulting truncated part still included the essential cyclase domain, and therefore represents one of our favorite BioBricks: [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1045003 BBa_K1045003]!