Team:Edinburgh/Project/Results/Bioethanol Results

From 2013.igem.org

Krothschild (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (10 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

The same set of primers was used for sequencing of pdc-adhB fusion construct. Obtained results indicate that the fused state was present on a DNA level: | The same set of primers was used for sequencing of pdc-adhB fusion construct. Obtained results indicate that the fused state was present on a DNA level: | ||

| - | + | [[File:chromatogram_data_fusion.zip]] | |

| - | Presence of following DNA sequence: GTAAACCGGTGAATAAACTGCTGGCATCAAGCACCTTTTATATCC corresponding to reverse complement of reverse primer followed by forward primer sequences indicates that gene fusion was obtained. | + | |

| + | Note: Presence of following DNA sequence: GTAAACCGGTGAATAAACTGCTGGCATCAAGCACCTTTTATATCC corresponding to reverse complement of the reverse primer followed by the forward primer sequences indicates that the gene fusion was obtained. | ||

<h2> Protein level evidence: </h2> | <h2> Protein level evidence: </h2> | ||

| - | In order to express fused pdc-adhB the construct was placed under the control of J33207 – IPTG inducible promoter combined with LacZ reporter. | + | In order to express fused pdc-adhB, the construct was placed under the control of the J33207 – IPTG inducible promoter combined with LacZ reporter. |

| - | Full grown cultures expressing pdc-adhB fusion and non-fusion were lysed and analysed on SDS-PAGE | + | Full grown cultures expressing pdc-adhB fusion and non-fusion were lysed and analysed on SDS-PAGE (Figure 4). |

[[File:Bioethanol_results4.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results4.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 4.''' | + | '''Figure 4.''' This shows the SDS-PAGE following Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 staining. Within the induced non-fusion lanes, two intense bands are present (with size corresponding to pdc and adhB). Within the induced fusion lanes, the previously described bands are missing but an additional band of increased size is observed. In the vector only lane, none of above described bands are present. To see full SDS-PAGE go to Appendix Figure 2 |

| - | In order to present that functionality of adhB is attributed to a peptide of a different mass in fusion state than in non-fusion state a native PAGE was performed. | + | In order to present that functionality of adhB is attributed to a peptide of a different mass in fusion state than in non-fusion state, a native PAGE was performed (Figure 5). |

[[File:Bioethanol_results5.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results5.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 5.''' Native PAGE stained for AdhB activity. Enzymatic activity can be attributed to a peptide of an increased mass in the fusion state than in non-fusion state. | + | '''Figure 5.''' Native PAGE stained for AdhB activity. Enzymatic activity can be attributed to a peptide of an increased mass in the fusion state than in non-fusion state. |

| - | Moreover, it was presented that pdc and adhB activity can be attributed to same gel band showing that fusion state was indeed obtained | + | Moreover, it was presented that the pdc and adhB activity can be attributed to same gel band showing that fusion state was indeed obtained (Figure 6). |

[[File:Bioethanol_results6.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results6.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 6.''' Native pages with adhB and pdc | + | '''Figure 6.''' Native pages with both adhB and pdc stained. Both activities are present in a band just below the well. Due to the different acrylamide concentrations used, the fused protein was unable to migrate into the gel as opposed to in PAGE gel present in Figure 5. |

<h3>Ethanol production using fused pdc and adhB:</h3> | <h3>Ethanol production using fused pdc and adhB:</h3> | ||

| - | Pdc and adhB catalyse conversion of pyruvate to ethanol via acetaldehyde intermediate | + | Pdc and adhB catalyse conversion of pyruvate to ethanol via acetaldehyde intermediate. |

| - | + | We hypothesized that generation of the pdc-adhB fusion would increase ethanol yields. This suggestion was based on two main observations: | |

| - | 1. Flow of substrate from one enzyme to another should be facilitated in fused protein state; | + | 1. Flow of substrate from one enzyme to another should be facilitated in the fused protein state; |

| - | 2. Due to better flow of intermediate product less of it should be released into the cell. As this intermediate is a toxic acetaldehyde moiety the fusion state could decrease toxicity of ethanol production | + | 2. Due to better flow of the intermediate product, less of it should be released into the cell. As this intermediate is a toxic acetaldehyde moiety, the fusion state could decrease toxicity of ethanol production for the bacterial cell; |

| - | It was established that highest ethanol yields | + | It was established that the highest ethanol yields could be achieved in glucose as a carbon source. LB+ 4% glucose was used for ethanol production. Following ethanol levels were achieved in the experiment (Figure 7). |

[[File:Bioethanol_results7.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results7.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 7.''' | + | '''Figure 7.''' This is an ethanol production graph. The cultures were first incubated for 24 hr in an aerobic environment. Following that, they were switched into fermentative conditions for 48 hr. For statistical analysis considering multiple runs of the experiment see Figures 3 and 4 in Appendix |

<h2>Analysis of adhB activity in the fusion protein state:</h2> | <h2>Analysis of adhB activity in the fusion protein state:</h2> | ||

| - | It was observed that the adhB activity seems to be lower in the | + | It was observed that the adhB activity seems to be lower in the fused state than in the non-fused state (Figure 5). To quantify this an NAD+ reduction assay was performed (Figure 8). |

[[File:Bioethanol_results8.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results8.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 8.''' OD340 readings over time correspond to ctivity of adhB in fused (blue) and non-fused (red) state. | + | '''Figure 8.''' OD340 readings over time correspond to ctivity of adhB in the fused (blue) and non-fused (red) state. |

| - | From those measurements and protein concentration data obtained using Pierce assay specific activity was calculated: | + | From those measurements and protein concentration data obtained using the Pierce assay, specific activity was calculated: |

AdhB – fusion: 0.091 U/mg. | AdhB – fusion: 0.091 U/mg. | ||

AdhB – non-fusion: 1.79 U/mg | AdhB – non-fusion: 1.79 U/mg | ||

| - | Those indicate that | + | Those numbers indicate that adhB has lower activity in the fusion state. Yet despite this, an increased ethanol concentration was obtained. This observation provides evidence that the fusion itself is the reason for the increased ethanol production, not highier activity of one enzyme in fusion state. |

| - | Microscopy of cells expressing fusion and non-fusion constructs : | + | <h2>Microscopy of cells expressing fusion and non-fusion constructs:</h2> |

| - | + | A phase contrast microscopy of cell cultures (Figure 9) indicates that cells expressing fused pdc-adhB constructs are more likely to be elongated. | |

[[File:Bioethanol_results9.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results9.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 9.''' Phase contrast microscopy images (x100) obtained for selected cultures. To see full microscopy slides | + | '''Figure 9.''' Phase contrast microscopy images (x100) obtained for selected cultures. To see full microscopy slides see Appendix Figures 5 to 7. This might be explained by the possible formation of long clusters of fused proteins. This phenomenon could be achieved due to the dimeric nature of the active adhB as well as the tetrameric nature of the active pdc. |

| - | + | ||

| - | This might be explained by possible formation of long clusters of fused proteins. This | + | |

<h3>Ethanol production from waste :</h3> | <h3>Ethanol production from waste :</h3> | ||

| - | In order to facilitate ethanol production we | + | In order to facilitate ethanol production, we decided to build a device, which would convert either D- or L-lactate straight to ethanol (Figure 10). |

[[File:Bioethanol_results10.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results10.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 10.''' | + | '''Figure 10.''' This shows the direct conversion of lactic acid to ethanol using LDH and our fusion protein. Note that the NADH co-factor is recycled over the course of reaction. This is what delineates the reversible steps catalysed by both LDH and ADHB. |

| - | In order to achieve direct conversion of | + | In order to achieve the direct conversion of lactate to ethanol, L-LDH and D-LDH were cloned with their native RBS (Figure 11). |

[[File:Bioethanol_results11.png]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results11.png]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 11.''' PCR products have an expected size of about | + | '''Figure 11.''' PCR products have an expected size of about 1 kb. |

| - | + | Then the genes were placed under the control of BBa_J33207 and transformed into competent ''E. coli'' cells expressing the PDC-ADHB fusion protein (in pSB1K3). Double-transformed cells were plated out on CML+KAN plates. Phenotypic differences were observed in resulting colony apperance (Figure 12) | |

[[File:Bioethanol_results12.png|600px]] | [[File:Bioethanol_results12.png|600px]] | ||

| - | '''Figure 12.''' Cells overexpressing the L-LDH (right) are much smaller than those overexpressing D-LDH (left). We hypothesise that this could be attributed to increased ethanol production using this enzyme. | + | '''Figure 12.''' Cells overexpressing the L-LDH (right) are much smaller than those overexpressing D-LDH (left). We hypothesise that this could be attributed to the increased ethanol production using this enzyme. |

<h3>Production of ethanol in ''B. subtilis'' :</h3> | <h3>Production of ethanol in ''B. subtilis'' :</h3> | ||

| - | The pLac_LacZ_fused_PDC_ADHB construct would not enable expression of the | + | The pLac_LacZ_fused_PDC_ADHB construct would not enable expression of the ethanol production module in ''B. subtilis'' due to low activity of ''E. coli'' pLac promoter in this particular bacterium. In order to overcome that, MABEL primers were designed, which will convert the pLac promoter into the pSpac promoter (see Appendix for details). |

| - | Following a | + | Following a successful PCR and a blunt-ended ligation, the construct was transferred into pTG262 vector and used for transformation of competent ''B. subtilis'' 168. Ethanol production was then induced using IPTG. |

</div> | </div> | ||

{{Team:Edinburgh/Footer}} | {{Team:Edinburgh/Footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 01:06, 5 October 2013

Contents |

Generation of pET fusion:

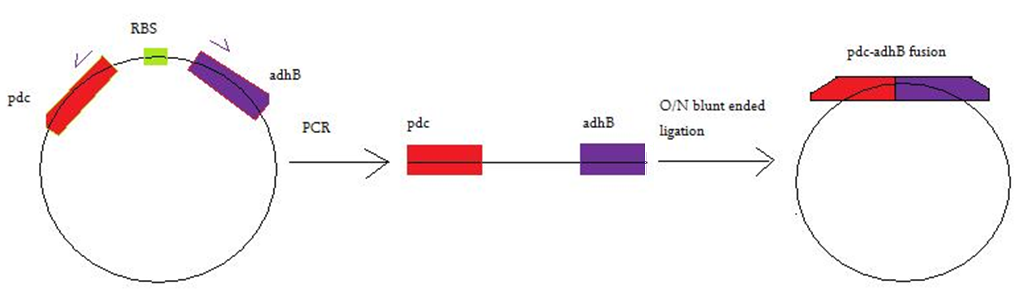

In order to generate a fusion of Pyruvate decarboxylase (pdc) and Alcohol dehydrogense B (adhB), Mutagenesis with Blunt- Ended Ligation (MABEL) was used. A pair of primers were designed complementary with 3' end of pdc and 5' end of adhB. Figure 1 represents the MABEL process.

Figure 1. Represents MABEL process used for generation of fused pdc-adhB construct. The primer sequences used are: forward: GCATCAAGCACCTTTTATATCC and reverse: CAGCAGTTTATTCACCGGTTTAC. See appendix Figure 1 for full details on the part sequence, primer binding sites and deleted region.

Generated PCR product was analysed on an agarose gel (Figure 2):

Figure 2. This shows the presence of a single PCR product of correct size (app. 6000 bp) on a 0.8% agarose gel. A 1 kb NEB DNA ladder was used, along with several replicates of the reaction were loaded on a gel.

Evidence for presence of fused pdc-adhB:

DNA level evidence:

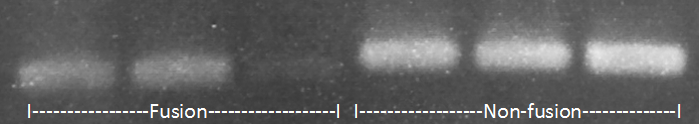

We then designed primers to amplify the region of fusion (region with deleted RBS), which were used for PCR on the fused and non-fused pdc and adhB.

Figure 3. 2.5% agarose gel analysing PCR product created using primers amplifying the region of putative gene fusion. PCR products amplyfing fused protein region (first 3 lanes) are smaller than those amplyfing the same region in non-fused genes(last 3 lanes).

The same set of primers was used for sequencing of pdc-adhB fusion construct. Obtained results indicate that the fused state was present on a DNA level:

File:Chromatogram data fusion.zip

Note: Presence of following DNA sequence: GTAAACCGGTGAATAAACTGCTGGCATCAAGCACCTTTTATATCC corresponding to reverse complement of the reverse primer followed by the forward primer sequences indicates that the gene fusion was obtained.

Protein level evidence:

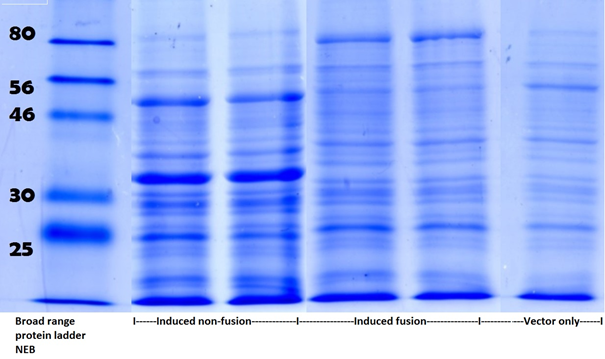

In order to express fused pdc-adhB, the construct was placed under the control of the J33207 – IPTG inducible promoter combined with LacZ reporter.

Full grown cultures expressing pdc-adhB fusion and non-fusion were lysed and analysed on SDS-PAGE (Figure 4).

Figure 4. This shows the SDS-PAGE following Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 staining. Within the induced non-fusion lanes, two intense bands are present (with size corresponding to pdc and adhB). Within the induced fusion lanes, the previously described bands are missing but an additional band of increased size is observed. In the vector only lane, none of above described bands are present. To see full SDS-PAGE go to Appendix Figure 2

In order to present that functionality of adhB is attributed to a peptide of a different mass in fusion state than in non-fusion state, a native PAGE was performed (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Native PAGE stained for AdhB activity. Enzymatic activity can be attributed to a peptide of an increased mass in the fusion state than in non-fusion state.

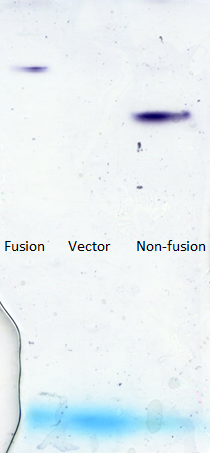

Moreover, it was presented that the pdc and adhB activity can be attributed to same gel band showing that fusion state was indeed obtained (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Native pages with both adhB and pdc stained. Both activities are present in a band just below the well. Due to the different acrylamide concentrations used, the fused protein was unable to migrate into the gel as opposed to in PAGE gel present in Figure 5.

Ethanol production using fused pdc and adhB:

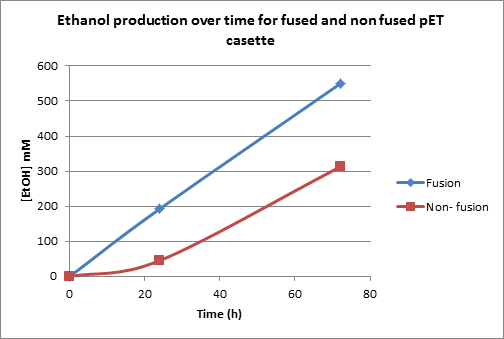

Pdc and adhB catalyse conversion of pyruvate to ethanol via acetaldehyde intermediate.

We hypothesized that generation of the pdc-adhB fusion would increase ethanol yields. This suggestion was based on two main observations: 1. Flow of substrate from one enzyme to another should be facilitated in the fused protein state; 2. Due to better flow of the intermediate product, less of it should be released into the cell. As this intermediate is a toxic acetaldehyde moiety, the fusion state could decrease toxicity of ethanol production for the bacterial cell;

It was established that the highest ethanol yields could be achieved in glucose as a carbon source. LB+ 4% glucose was used for ethanol production. Following ethanol levels were achieved in the experiment (Figure 7).

Figure 7. This is an ethanol production graph. The cultures were first incubated for 24 hr in an aerobic environment. Following that, they were switched into fermentative conditions for 48 hr. For statistical analysis considering multiple runs of the experiment see Figures 3 and 4 in Appendix

Analysis of adhB activity in the fusion protein state:

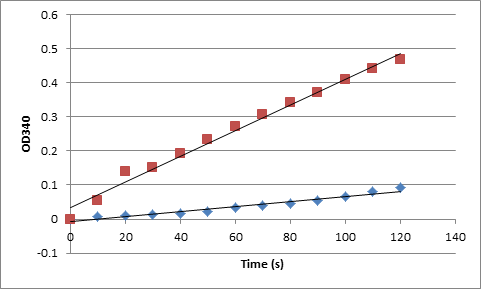

It was observed that the adhB activity seems to be lower in the fused state than in the non-fused state (Figure 5). To quantify this an NAD+ reduction assay was performed (Figure 8).

Figure 8. OD340 readings over time correspond to ctivity of adhB in the fused (blue) and non-fused (red) state. From those measurements and protein concentration data obtained using the Pierce assay, specific activity was calculated: AdhB – fusion: 0.091 U/mg. AdhB – non-fusion: 1.79 U/mg

Those numbers indicate that adhB has lower activity in the fusion state. Yet despite this, an increased ethanol concentration was obtained. This observation provides evidence that the fusion itself is the reason for the increased ethanol production, not highier activity of one enzyme in fusion state.

Microscopy of cells expressing fusion and non-fusion constructs:

A phase contrast microscopy of cell cultures (Figure 9) indicates that cells expressing fused pdc-adhB constructs are more likely to be elongated.

Figure 9. Phase contrast microscopy images (x100) obtained for selected cultures. To see full microscopy slides see Appendix Figures 5 to 7. This might be explained by the possible formation of long clusters of fused proteins. This phenomenon could be achieved due to the dimeric nature of the active adhB as well as the tetrameric nature of the active pdc.

Ethanol production from waste :

In order to facilitate ethanol production, we decided to build a device, which would convert either D- or L-lactate straight to ethanol (Figure 10).

Figure 10. This shows the direct conversion of lactic acid to ethanol using LDH and our fusion protein. Note that the NADH co-factor is recycled over the course of reaction. This is what delineates the reversible steps catalysed by both LDH and ADHB.

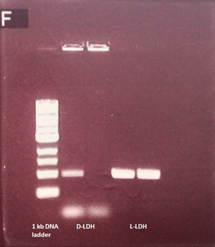

In order to achieve the direct conversion of lactate to ethanol, L-LDH and D-LDH were cloned with their native RBS (Figure 11).

Figure 11. PCR products have an expected size of about 1 kb.

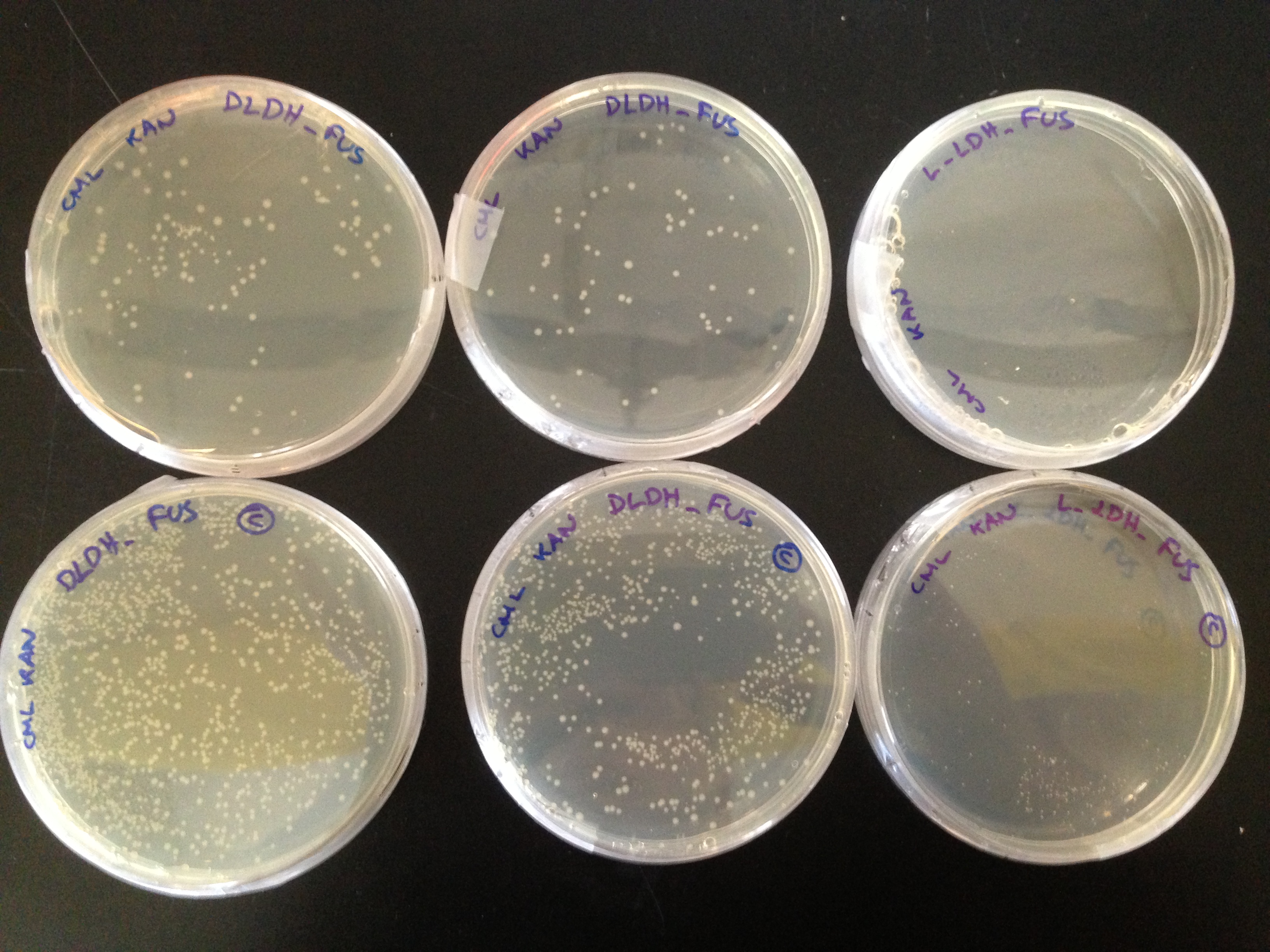

Then the genes were placed under the control of BBa_J33207 and transformed into competent E. coli cells expressing the PDC-ADHB fusion protein (in pSB1K3). Double-transformed cells were plated out on CML+KAN plates. Phenotypic differences were observed in resulting colony apperance (Figure 12)

Figure 12. Cells overexpressing the L-LDH (right) are much smaller than those overexpressing D-LDH (left). We hypothesise that this could be attributed to the increased ethanol production using this enzyme.

Production of ethanol in B. subtilis :

The pLac_LacZ_fused_PDC_ADHB construct would not enable expression of the ethanol production module in B. subtilis due to low activity of E. coli pLac promoter in this particular bacterium. In order to overcome that, MABEL primers were designed, which will convert the pLac promoter into the pSpac promoter (see Appendix for details).

Following a successful PCR and a blunt-ended ligation, the construct was transferred into pTG262 vector and used for transformation of competent B. subtilis 168. Ethanol production was then induced using IPTG.

|

| | | |

|

| This iGEM team has been funded by the MSD Scottish Life Sciences Fund. The opinions expressed by this iGEM team are those of the team members and do not necessarily represent those of MSD | |||||

"

"