Team:UGent/LiteratureStudy

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

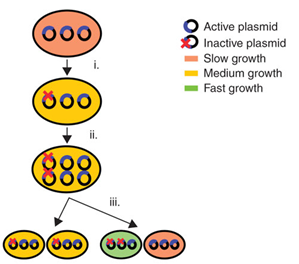

| - | <p></html>[[File:UGent_2013_AlleleSegregation.png|thumb|250px|Allele segregation results in a rapid loss of productivity in plasmids | + | <p></html>[[File:UGent_2013_AlleleSegregation.png|thumb|250px|Allele segregation results in a rapid loss of productivity in plasmids]]<html> |

<br></p> | <br></p> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

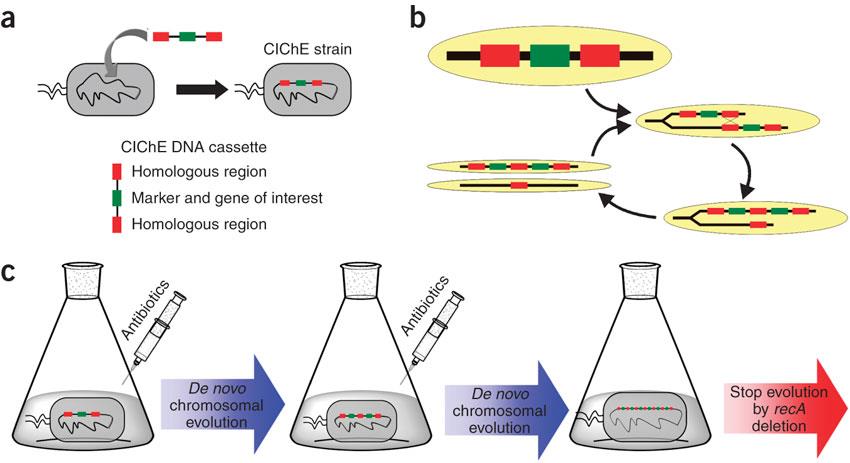

<p>CIChE works as follows: First a construct, containing the gene(s) of interest and the antibiotic marker <i>chloramphenicol acetyl transferase</i> (<i>cat</i>) flanked by homologous regions, is delivered to and subsequently integrated into the <i>E. coli</i> genome. The construct can be amplified in the genome through tandem gene duplication by <i>recA</i> homologous recombination. Then the strain is cultured in increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol, providing a growth advantage for cells with increased repeats of the construct and thereby selecting for bacteria with a higher gene copy number (<b>Figure</b>).</p> | <p>CIChE works as follows: First a construct, containing the gene(s) of interest and the antibiotic marker <i>chloramphenicol acetyl transferase</i> (<i>cat</i>) flanked by homologous regions, is delivered to and subsequently integrated into the <i>E. coli</i> genome. The construct can be amplified in the genome through tandem gene duplication by <i>recA</i> homologous recombination. Then the strain is cultured in increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol, providing a growth advantage for cells with increased repeats of the construct and thereby selecting for bacteria with a higher gene copy number (<b>Figure</b>).</p> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | [[File:UGent_2013_CIChE.jpg|thumb|400px|center|Tyo et al., 2009 | + | [[File:UGent_2013_CIChE.jpg|thumb|400px|center|Tyo et al., 2009]] |

<html> | <html> | ||

<p>This process is called chromosomal evolution. When the desired gene copy number is reached <i>recA</i> is deleted, thereby fixing the copy number.</p> | <p>This process is called chromosomal evolution. When the desired gene copy number is reached <i>recA</i> is deleted, thereby fixing the copy number.</p> | ||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

<p></html> | <p></html> | ||

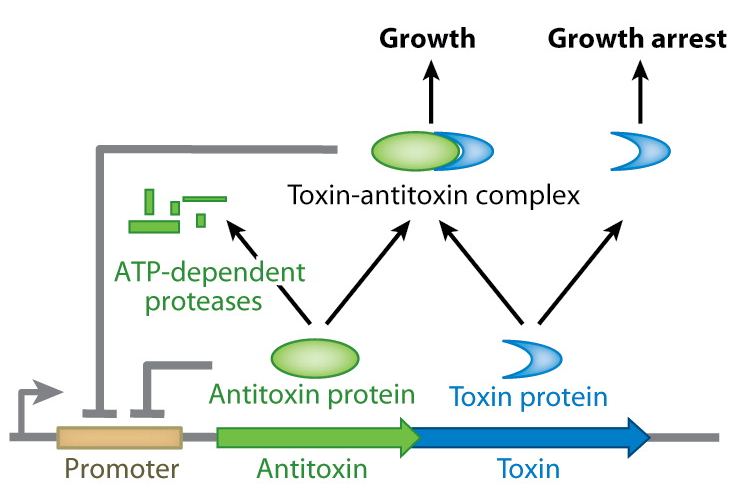

| - | [[File:UGent_2013_TA_TypeII.png|thumb|320px|center|<b>Mechanism of type II TA systems.</b> The antitoxin protein inhibits the toxin protein by forming a sstable complex with the toxin. This complex (as well as the antitoxin itself) is part of a feedback inhibition of the promoter. | + | [[File:UGent_2013_TA_TypeII.png|thumb|320px|center|<b>Mechanism of type II TA systems.</b> The antitoxin protein inhibits the toxin protein by forming a sstable complex with the toxin. This complex (as well as the antitoxin itself) is part of a feedback inhibition of the promoter.]] |

<html></p> | <html></p> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 128: | Line 128: | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

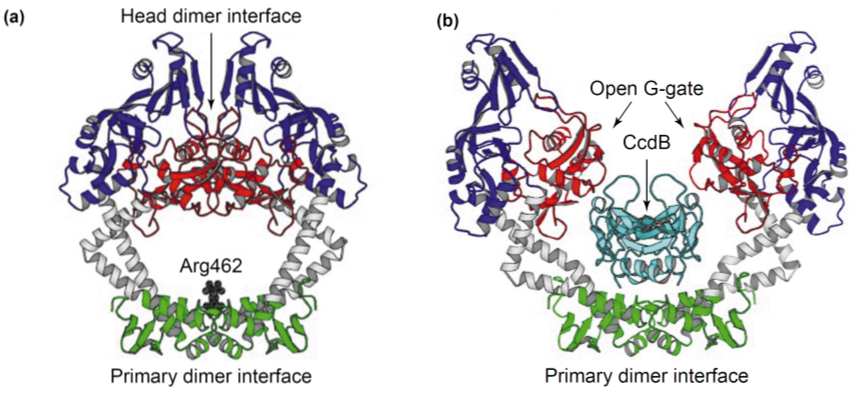

| - | [[File:UGent_2013_GyrA_CcdB.png|thumb|360px|center|<b>Interaction between CcdB and the A subunit of DNA gyrase (GyrA).</b> (a) Free GyrA59 (the 59 kDa amino-terminal breaking rejoining domain of GyrA) in its closed conformation. (b) Opening up of the GyrA dimer creates space for a CcdB dimer. When CcdB binds to this conformation, normal working mechanism of gyrase is prohibited. | + | [[File:UGent_2013_GyrA_CcdB.png|thumb|360px|center|<b>Interaction between CcdB and the A subunit of DNA gyrase (GyrA).</b> (a) Free GyrA59 (the 59 kDa amino-terminal breaking rejoining domain of GyrA) in its closed conformation. (b) Opening up of the GyrA dimer creates space for a CcdB dimer. When CcdB binds to this conformation, normal working mechanism of gyrase is prohibited.]] |

<html> | <html> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 143: | Line 143: | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | [[File:UGent_2013_Model.jpg|thumb|700px|center|Our model for CIChE | + | [[File:UGent_2013_Model.jpg|thumb|700px|center|Our model for CIChE]] |

<html> | <html> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:45, 5 October 2013

|

You can read our entire literature study about our new model for stabilised gene duplication here. Below you can read the most important aspects of it. Introduction: high gene expression in industrial biotechnologyThe main goal of industrial biotechnology is to increase the yield of biochemical products using microorganisms as production hosts. This includes engineering large synthetic pathways and improving their expression. Overexpression of genes has mainly been achieved by using high or medium copy plasmids. However, studies have demonstrated that plasmid-bearing cells lose their productivity fairly quickly as a result of genetic instability.

In industrial biotechnology, a common technique to express new synthetic products and pathways is the use of plasmids as vectors. Plasmids are circular pieces of DNA. They are easy to insert into cells and replicate independently from the genome, allowing strong gene expression. Overexpression is easily achieved by using plasmids with a medium or high copy number, different promoter systems, ribosome binding sites (RBS), etc. Thanks to plasmids, the industrial biotechnology has grown substantially over the past years. However, the use of plasmids entails some important disadvantages: plasmid maintenance imposes a metabolic burden on cells and plasmids suffer from genetic instability. Metabolic burdenWhen plasmids are present in cells and replicate, they create a metabolic burden. This is defined by Bentley et al. (1990) as “the amount of resources that are taken from the host cell metabolism for foreign DNA maintenance and replication”. As a result, metabolic load causes many alterations to the physiology and metabolism of the cell and reduces the cellular fitness. The most common change is a delayed growth. This can be caused by the fact that new pathways for energy generation are activated due to the competition between cell propagation and plasmid replication. This growth retardation leads to a lower yield of the desired product. Genetic instabilityPlasmids are genetically instable due to three processes: segregational instability, structural instability and allele segregation.

Therefore a new method was developed for the overexpression of a gene of interest in the bacterial chromosome: Chemically Inducible Chromosomal evolution (CIChE). In this technique the chromosome is evolved to contain a higher number of gene copies by adding a chemical inducer.

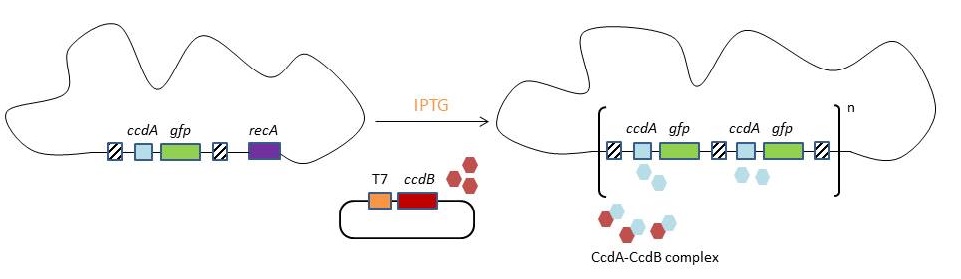

In 2009, Tyo et al. developed a technique for the stable, high copy expression of a gene of interest in E. coli without the use of high copy number plasmids, thus avoiding their previously stated negative characteristics. They called this plasmid-free, high gene copy expression system ‘chemically inducible chromosomal evolution’. In this method, the gene of interest is integrated in the microbial genome and then amplified to achieve multiple copies and reach the desired expression level. Genomic integration guarantees ordered inheritance, resolving the problem of allele segregation. CIChE works as follows: First a construct, containing the gene(s) of interest and the antibiotic marker chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (cat) flanked by homologous regions, is delivered to and subsequently integrated into the E. coli genome. The construct can be amplified in the genome through tandem gene duplication by recA homologous recombination. Then the strain is cultured in increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol, providing a growth advantage for cells with increased repeats of the construct and thereby selecting for bacteria with a higher gene copy number (Figure).

This process is called chromosomal evolution. When the desired gene copy number is reached recA is deleted, thereby fixing the copy number. The use of CIChE-strains poses several advantages. They require no selection markers and can be cultured without the addition of antibiotics to the medium. This is in contrast to strains containing plasmids, which still need antibiotic selection. Also, in CIChE-strains yields can be tuned by varying the antibiotic concentration during chromosomal evolution. CloseIt has been shown that approximately 40 and even up to 50 gene copies can be attained using chromosomal evolution. It has also been demonstrated that, while plasmid-bearing strains lose their productivity after 40 generations due to allele segregation, gene copy number and productivity of CIChE-strains remain stable even after 70 generations. This genetic stability is considered to be the most important asset of CIChE. The original model for CIChE, however, results in bacterial strains containing a large number of antibiotic resistance genes. To make this valuable technique more widely applicable in the industry, we developed a model for chromosomal evolution based on a toxin-antitoxin system instead of antibiotic resistance. | |||

"

"