Team:Paris Bettencourt/Project/Infiltrate

From 2013.igem.org

Background

Latent tuberculosis persists inside macrophages of the lungs, where it is partially protected from both the host immune system and conventional antibiotics.

Results

- We expressed the enzyme Trehalose Dimycolate Hydrolase (TDMH) in E.coli and showed that it is highly toxic to mycobacteria in culture.

- We expressed the lysteriolyin O (LLO) gene in E. coli and showed that it is capable of entering the macrophage cytosol.

- We co-infected macrophages with both mycobacteria and our engineered E. coli to characterize the resulting phagocytosis and killing.

BioBricks

Aim

To create an E. coli strain capable of entering the macrophage cytosol and delivering a lytic enzyme to kill mycobacteria.

Skip to Introduction

Skip to Design

Skip to Killing Assay

Skip to Drug Delivery

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the bacterium responsible for tuberculosis (TB), spreads by aerosol and infects its host through the airways. The bacterium is phagocytosed by macrophages in the lung, yet often evades death in the lysosome. Mtb can persist for years or even decades inside macrophages by inhibiting phagosome/lysosome fusion and supressing the normal acidification of the lysosome.

An efficient treatment for persistent TB must enter infected macrophages and kill the pathogen there. In our system, E. coli is both the vector and the therapeutic agent agent by expressing the gene LLO to enter macrophages and TDMH to kill mycobacteria.

BOX 1: Why is it difficult to treat tuberculosis?

- Mtb can survive and replicate for years inside the macrophages by supressing the normal process of phagocytosis.

- The cell wall of M. tuberculosis is thick, waxy and rich in mycolic acids. It it difficult to penetrate with a small-molecule drug.

- The pathogen grows very slowly inside macrophages. Most conventional antibiotics target processes like DNA replication that are specific to growing cells.

TDMH and the mycobacterial cell wall

Mycobacterium species share a characteristic cell wall: thick, waxy, hydrophobic, and rich in mycolic acids. The low permeability of the envelope to hydrophilic solutes contributes to the intrinsic drug tolerance in mycobacteria.

Trehalose Dimycolate Hydrolase (TDMH) is a cutinase-like serine esterase that triggers rapid lysis of the mycobacterial cell wall by degrading the mycolate layer. The enzyme was first isolated from Mycobacterium smegmatis and subsequently shown to hydrolyze purified TDM from various mycobacterial species. Exposure to TDMH triggers an immediate release of free mycolic acids, ultimately leading to lysis of many mycobacteria including Mtb (Yang et al. 2012).

We have used M. smegmatis as a model system because Mtb are highly pathogenic and difficult to culture in the lab. M. smegmatis is a close relative of Mtb, shares many of its membrane properties, and is commonly used as a stand-in for Mtb physiology in the lab.

In our system, described in the methods below, we used E. coli BL21 (DE3) as a chassis to express TDMH from an IPTG-inducible strong T7 promoter.

Killing mycobacteria with TDMH

Figure 1 (below) shows the killing of M. smegmatis with TDMH expressed by E. coli. We mixed liquid cultures of E. coli and M. smegmatis at equal cell densities as determined by plating assays. When expression of TMDH was induced with IPTG, nearly 99% of the M. smegmatis were killed within six hours. We saw no change in viability in cultures of M. smegmatis alone or when mixed with uninduced E. coli.

We next sought to quantify the effectiveness of TDMH killing. We mixed induced E. coli and mycobacteria in different ratios and used plating assays to measure viability. As shown in figure 2 mycobacterial killing displayed dose dependence on the E. coli cell density. Small numbers of E. coli could kill many mycobacteria. For example, in mixed populations with 100 mycobactera for each E. coli, we still observed >50% mycobacterial killing after 2 hours. This indicates that, on average, each E. coli produced enough TDMH to kill 50 mycobacterial. We reason that this killing may be even more effective inside macrophages, where constrained volumes will increase the effective TDMH concentration.

Figure 0 Experimental setup of the M.smegmatis killing assay.

Figure 1 TDMH-expressing E. coli kill mycobacteria in culture.

Figure 2 Dose-dependence in killing of mycobacteria by E. coli.

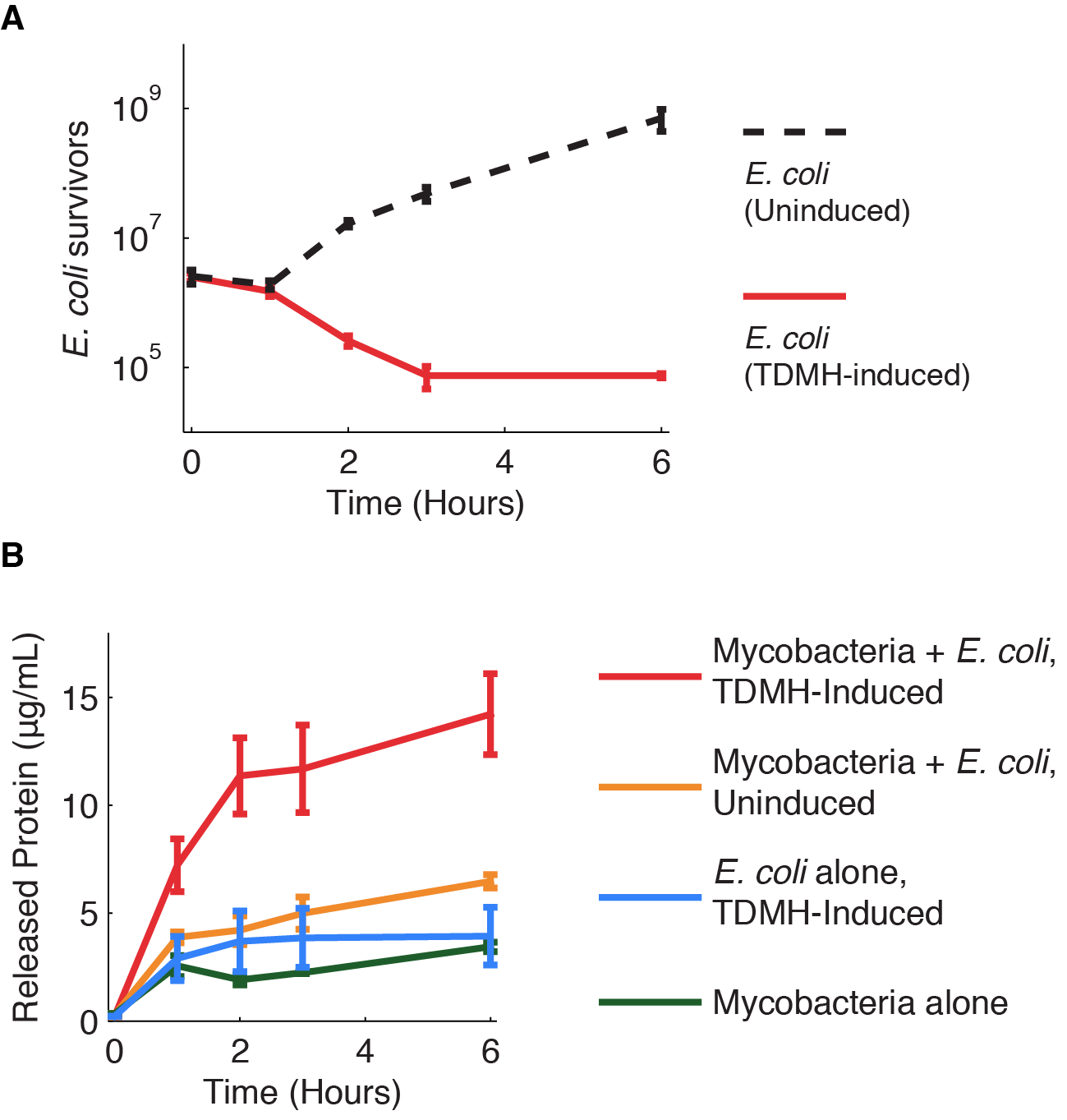

We investigated further the mechanism of TDMH-mediated cell killing. The TDMH enyme in our system does not carry a secretion tag. Therefore, lysis of the E. coli membrane is probably required for the protein to reach (and lyse) M. smegmatis. We used plating assays to investigate the effect of TDMH induction on E. coli viability and Bradford assays to measure released protein. The results are presented in figure 3.

Figure 3A shows that inducing TDMH-expressing E. coli with IPTG rapidly kills the E. coli. In figure 3B, we show that inducing TDMH expression increases the concentration of free protein in the media. In our model, TDMH induction leads to spontaneous lysis of TDMH-expressing E. coli. This could be simply due to the extremely high protein expression levels driven by the T7 promoter, or it may be partially due to the esterase activities of the TDMH enzyme. Once the TDMH is released from the E. coli it is free to act on mycobacterial membranes, causing lysis and the release of additional proteins.

Figure 3 Induction of TDMH kills E. coli and relases protein to the media.

Programmed drug delivery with LLO

Listeria monocytogenes is a bacterial pathogen that replicates in the cytosol of mammalian cells. The pathogen is initially internalized in host phagosomes, then lyses them to obtain access to the cytosol. A single gene, LLO, is responsible for this activity and is sufficient to convey the phenotype to E. coli.

The LLO protein is activated by the low pH of the lysosme. By forming large pores in the lysosomal membrane, it allows protein delivery to the cytosol of macrophages (Higgins et al. 1999). Using E. coli as a protein vector means we don't need to isolate and purify the TDMH enzyme.

We hypothesized that a bacterial delivery system could be efficient and specific in targeting mycobacterial-infected macrophages. In effect, we might take advantage of the natural tendency of macrophages to phagocytose E. coli and their enzymatic payload.

Because LLO expression is known to be associated with Listeria pathogenicity, we took extra precautions in our cloning and experiments. These measures are detailed on our team safety page. Briefly, we worked in a Biosafety Level 2 lab under the supervision of two full-time lab managers. We researched and complied with French national and insitutional biosafety rules as they apply to this gene.

Figure 7 Experimental design of the killing assay inside the macrophages. We infected them with M.smegmatis and washed after 1 hour. Then, we infected them with E.coli and washed after 1 hour. The end of this final infection step refers to the time 0 on our graphs. At this time we started the observation under the microscope

E. coli and M. smegmatis coinfections

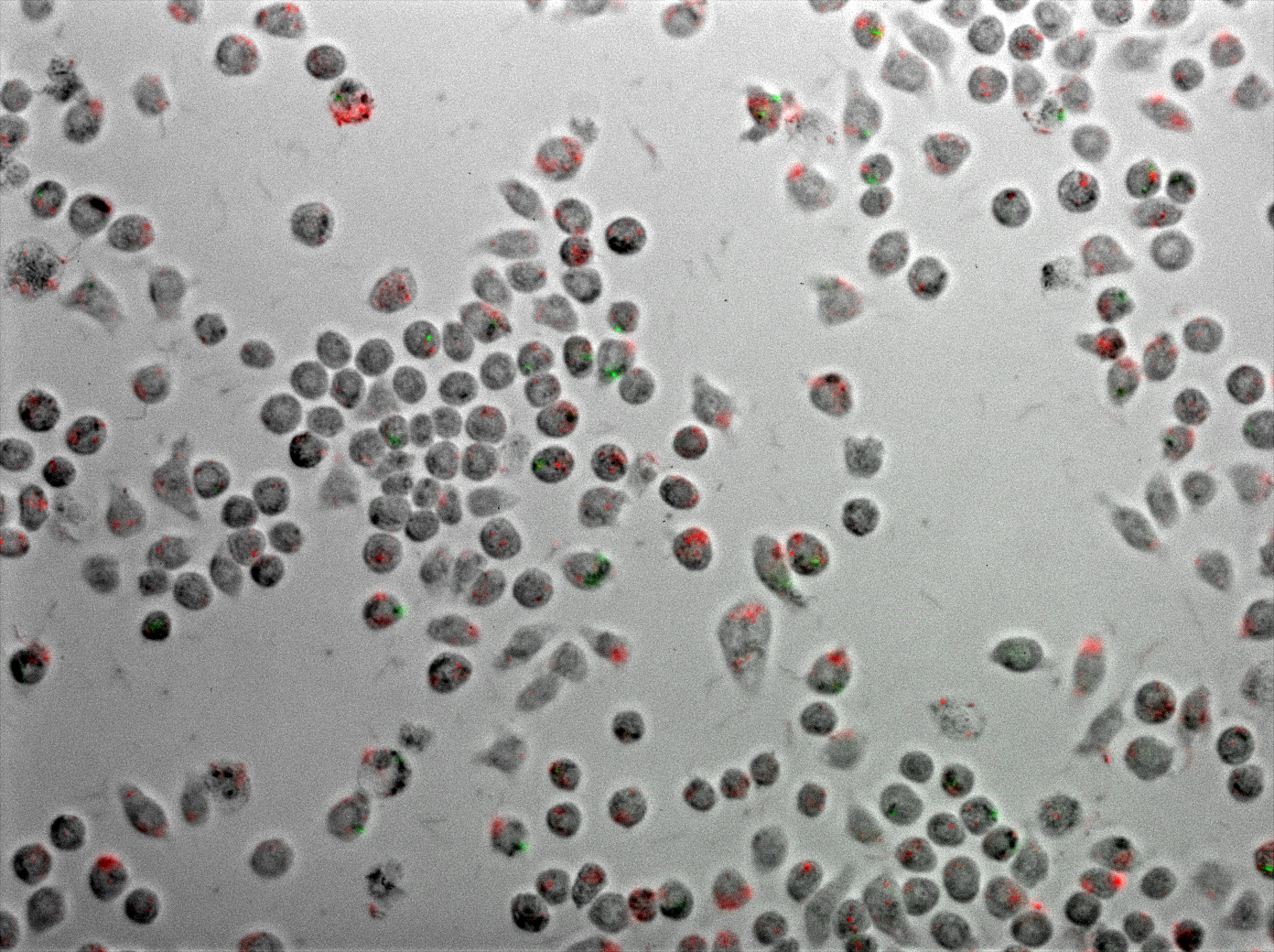

Figure 4 displays J774 macrophages one hour after coinfection with E. coli and M. smegmatis. As described in the methods, the E. coli express TDMH and LLO and fluorescent mRFP as a label. The M. smegmatis express GFP as a label, but are otherwise wild type.

The two movies displayed in figure 5 are time-lapse microscopy of live coinfected macrophages collected over a period of 6 hours. Fluorescence patterns revealing the localization of E. coli and M. smegmatis within the macrophages are relatively stable over this time period.

We next applied quantitative microscopy to characterize the behavior of our system inside live macrophages. We imaged macrophage populations under several conditions and time points and scored their rates of infection with E. coli, M. smegmatis or both. In all we scored over 13,000 individual cells collected from more than 100 separate images.

Figure 4 Coinfection of J774 macrophages with mycobacteria and E. coli expressing TDMH and LLO

Figure 5 Temporal dynamics of macrophages coinfected with E. coli and M. smegmatis.

Conclusions and continuing work

We have shown that E. coli can effectively kill mycobacteria in culture by expressing the TDMH enzyme, now a BioBrick. We have further shown that E. coli and mycobateria may co-localize within macrophages, where LLO-based systems can effectively deliver protein payloads.

In the coming weeks, we will continue to refine our cell culture techniques to precisely characterize the effectiveness of our system in situ, within the living macrophage.

Figure 6 The effect of TDMH-induced E. coli on macrophage infection rates after 3 hours.

Bibliography

- Yang Y, Bhatti A, Ke D, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Lenaerts A, Kremer L, Guerardel Y, Zhang P, Ojha AK (2012) : Exposure to a cutinase-like serine esterase triggers rapid lysis of multiple mycobacterial species. J Biol Chem. 2013 Jan 4;288(1):382-92.

- Rajesh Jayachandran, Varadharajan Sundaramurthy, Benoit Combaluzier , Philipp Mueller, Hannelie Korf, Kris Huygen, Toru Miyazaki, Imke Albrecht, Jan Massner, Jean Pieters (2007) : Survival of Mycobacteria in Macrophages Is Mediated by Coronin 1-Dependent Activation of Calcineurin. Cell, Volume 130, Issue 1, 13 July 2007, Pages 12-14

"

"

+33 1 44 41 25 22/25

+33 1 44 41 25 22/25