Team:SydneyUni Australia/Project/Design

From 2013.igem.org

Gibson

Gibson Assembly *should* make for a much easier, simpler, rapid assembly of different genes than conventional PCR and cloning, plus there’s much more flexibility for optimisation through gene synthesis.

- The assembly works on fragments of DNA with ~30bp of overlapping sequence, which is exposed as 5’ single-stranded overhangs by an exonuclease. A ligase joins the overlapping regions and a polymerase fills in any gaps left by the exonuclease. These enzymes can all work together in a single reaction tube with many different overlapping fragments, making the assembly a very, very simple activity. Gibson Assembly is based on the older technique of [http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/32/12/e98.full PCR Assembly], with the similar reliance on the initial construction of 200+bp fragments from smaller oligos, but with a greater degree of sequence fidelity due to less polymerase activity.

- Here’s a great introduction from IDT’s magazine, [http://www.idtdna.com/pages/decoded/decoded-articles/core-concepts/decoded/2012/01/10/isothermal-assembly-quick-easy-gene-construction DECODED], and a more in-depth webinar.

- If you’re historically-minded or want more detail, try the [http://diyhpl.us/~bryan/papers2/bio/venter/Enzymatic%20assembly%20of%20DNA%20molecules%20up%20to%20several%20hundred%20kilobases.pdf original paper] in which Gibson Assembly was described - or one of the coolest and most famous applications of Gibson, building a [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK84435/ synthetic genome].

Design

Choice of genes

Mox, chloroethanol dehydrogenase

- In sketches of our project (February-March), we planned to use Mox as the alcohol dehydrogenase converting chloroethanol to chloroacetaldehyde. After a little more research we discovered that this enzyme requires the co-factor PQQ, and unfortunately for us, this co-factor requires many genes for its synthesis, which would have made our constructs too complex (Khairnar et al, 2003).

- Mox had seemed like an obvious choice because it would be sourced from Xanthobacter autotrophicus GJ10, the most well-documented DCA-degrader ([http://mic.sgmjournals.org/content/133/1/85.full.pdf Janssen et al, 1987])

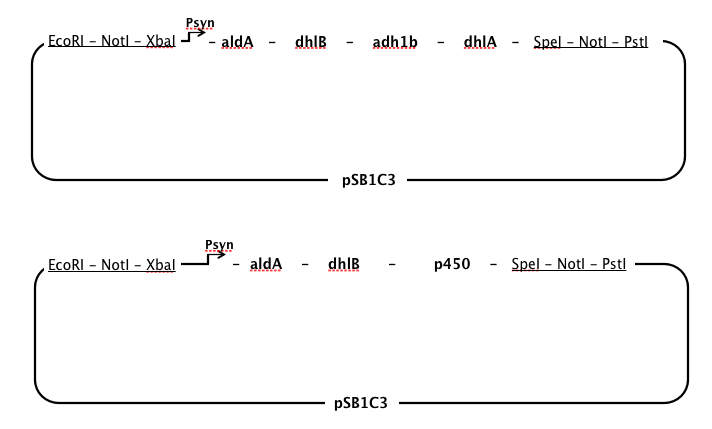

aldA, chloroacetaldehyde dehydrogenase, dhlB, haloacid dehalogenase, and dhlA, haloalkane dehalogenase

- We used a sequence for aldA from Xanthobacter autrophicus GJ10, but used sequences for dhlB and dhlA from a different strain, Xanthobacter autrophicus EL4, which was isolated and characterised in the Coleman lab. These two genes had been identified and cloned into pUC19 by Jake Munro, a research assistant in the Coleman lab. When our Gibson Assembly ran into problems, we continued to work with dhlB and dhlA from EL4 in our lab and submitted these two genes as parts.

- These genes are shared by a few different species of bacteria that degrade DCA (Janssen et al, 1994), and most have been conventionally characterised by extraction and heterologous expression of a single gene at a time.

ToMO, toluene-o-xylene monooxygenase

- Early in our project we showed that ToMO can degrade DCA. This would not only eliminate the need for something like PQQ-synthase, but also make for a shorter, less complex pathway involving just 3 enzymes (a monooxygenase, dehydrogenase and dehalogenase).

- We initially planned to synthesise ToMO, allowing us to remove forbidden restriction sites in the process (EcoRI and PstI). However, due to the sheer size of the monooxygenase cluster (~5kb) we could not afford to have this gene and all of our others synthesised.

- The gene we worked with initially has been extensively used for protein engineering by [http://fenske.che.psu.edu/faculty/wood/group/publications/pdf/ToMO%20TCE%20mutagenesis%20Vardar[1].pdf Varder & Wood (2005)].

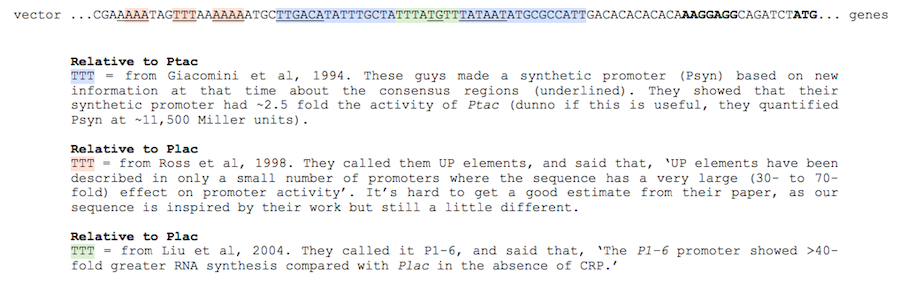

p450, cytochrome p450 monooxygenase

- Early in 2013 it was discovered that a monooxygenase from a Polaromonas sp. (JS666) was responsible for the initial steps of DCE and DCA degradation by heterologous expression in E. Coli ([http://aem.asm.org/content/79/7/2263.short) Nishino et al, 2013]). As far as we know, this enzyme effectively substitutes for ToMO in our pathway. Due to the shorter length of the three-gene p450 complex (~3kb) we decided to synthesise this enzyme instead of ToMO.

- The strain that carries this enzyme was first isolated from chloroethene contaminated sites by our primary supervisor, Nick Coleman, in the Stone Age ([http://aem.asm.org/content/68/6/2726.full Coleman et al, 2002]).

adh1b2, human liver alcohol dehydrogenase

- Human liver alcohol dehydrogenases have been shown to be active on a broad range of substrates, including haloalcohols and haloaldehydes ([http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/bi00870a034 Blair & Vallee, 1966]). They’ve also been expressed in E. Coli before (eg, [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00849.x/abstract Zheng et al, 1993]) using cDNA, but we were able to use a modified mRNA sequence from GenBank ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/BC033009 BC033009.2]). We were also able to choose between many types and classes of human liver enzyme, so we picked the one with the greatest turnover on ethanol as substrate (Edenberg, 2007).

Order of gene expression

- We chose to have a single, strong constitutive promoter in our pathway (see below, promoter), so it made sense to place our genes in order from last to first in order that at every step in the pathway there would be an excess of the enzyme required for the substrate, thus minimising the build-up of toxic intermediates.

- However, chloroacetaldehyde appears to be the most toxic of the intermediates produced while DCA is degraded (Janssen et al, 1994). It seemed necessary to position the enzyme specific to aldA immediately after the promoter to ensure that chloroacetaldehyde was rapidly removed from the cell.

Optimising a promoter

- We used a single synthetic promoter region based on Plac, but including changes that other people have shown increase RNA polymerase binding at the promoter region. All the changes were made to maximise RNA polymerase recognition.

Ribosome binding sites

We added or modfied the same RBS (AAGGAGG) before all our genes, for a mix of these reasons:

- The natural sequences we borrowed were from diverse hosts and didn’t contain RBS optimal for E. coli.

- Sequences were found as annotated coding regions without an RBS.

- Sequences had apparently sub-optimal RBSs too close or distant to the start codon.

Restriction sites

We removed all restriction sites in our sequences that are forbidden within Registry parts (EcoRI, NotI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI). This had to be done while ensuring not to change codon usage, or change to an rare codon. We used this [http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/cgi-bin/showcodon.cgi?species=83333&aa=11&style=GCG codon table].

Codon usage

An online [http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/RACC/ application] was used to identify codons rarely used by E. Coli. Again, changes had to be made while ensuring not to change codon usage. All stop codons were converted to the more common variant and included as double-stops (TAATAA).

GC content and hairpins

- The template we used for Gibson Assembly was purchased as gBlocks from IDT with their iGEM discount.

- Due to the assembly of larger fragments (~500bp) from smaller oligos (60-120bp) during gene synthesis, some regions need to be avoided. These are regions contain extremes of GC content and regions that form small, six-base hairpins. We tried to avoid problems by running all our sequences through the [http://www.idtdna.com/order/gblockwizard.aspx gBlocks wizard] before ordering, and addressing any problems. However, the application failed to find a few problematic regions and these caused delay before the arrival of our gBlocks.

References

- Blair, A. H., & Vallee, B. L. (1966). Some Catalytic Properties of Human Liver Alcohol Dehydrogenase*. Biochemistry, 5(6), 2026-2034.

- Edenberg, H. J. (2007). The genetics of alcohol metabolism: role of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase variants. Alcohol Research & Health.

- Giacomini, Alessio, et al. "Construction of multipurpose gene cartridges based on a novel synthetic promoter for high-level gene expression in Gram-negative bacteria." Gene 144.1 (1994): 17-24.

- Janssen, D. B., Keuning, S., & Witholt, B. (1987). Involvement of a quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase and an NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase in 2-chloroethanol metabolism in Xanthobacter autotrophicus GJ10. Journal of general microbiology, 133(1), 85-92.

- Janssen, D. B., Pries, F., & Van der Ploeg, J. R. (1994). Genetics and biochemistry of dehalogenating enzymes. Annual Reviews in Microbiology, 48(1), 163-191.

- Khairnar, N. P., Misra, H. S., & Apte, S. K. (2003). Pyrroloquinoline–quinone synthesized in< i> Escherichia coli</i> by pyrroloquinoline–quinone synthase of< i> Deinococcus radiodurans</i> plays a role beyond mineral phosphate solubilization. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 312(2), 303-308.

- Liu, Mofang, et al. "A mutant spacer sequence between-35 and-10 elements makes the Plac promoter hyperactive and cAMP receptor protein-independent."Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101.18 (2004): 6911-6916.

- Ross, Wilma, et al. "Escherichia coli promoters with UP elements of different strengths: modular structure of bacterial promoters." Journal of bacteriology180.20 (1998): 5375-5383.

- Vardar, G., & Wood, T. K. (2005). Protein engineering of toluene-o-xylene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1 for enhanced chlorinated ethene degradation and o-xylene oxidation. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 68(4), 510-517.

- Zheng, C. F., Wang, T. T., & Weiner, H. (1993). Cloning and Expression of the Full‐Length cDNAS Encoding Human Liver Class 1 and Class 2 Aldehyde Dehydrogenase. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 17(4), 828-831.

"

"