Team:Newcastle/Project/shape shifting

From 2013.igem.org

Contents |

Shape Shifting

Background

Most bacteria have evolved to have a cell wall, and those which do not, have cell walled ancestry (Trachtenberg 1998)(Errington 2013). The cell wall is a rigid structure which protects the bacteria from the variety of environmental hazards such as mechanical stress, osmotic rupture and lysis. The cell wall often serves as a docking point to many proteins including various receptors and adherence sites. In addition to these features, the cell wall provides the cell with a rigid boundary and helps bacteria to acquire and preserve their shape. In Bacillus subtilis a group of proteins termed Penicillin Binding Proteins (Pbp),along with other proteins, usually anchored in the cell wall, along with other proteins, are involved in the formation of the rod shape. When the cells lose their cell wall they automatically lose these proteins to the environment as they are being made. The cells lose their support and turn into a sphere as it is the most energetically favourable state (ratio of surface area to volume is minimal, and membrane curvature is more-or-less constant).

The idea

It has been previously observed that these cell wall-less bacteria can become elongated and 'squeeze' into the spaces with a smaller diameter than theirs. This fact sparked our interest and led us to ask some questions. L-forms are an improved secretory machine; the cell wall hinders excretion of some proteins. Could L-forms be used as a delivery vehicle in small or out-of-reach areas? Out of reach areas include intercellular spaces and micro-cracks in solid materials, which are smaller than 1 μm. B.subtilis in L-form state, can grow to large sizes before they divide. Is it possible to fill spaces of various shapes and sizes with L-forms?

To research into these areas, we were to manipulate L-forms microfluidics. Microfluidics allows manipulation of single cells via precise movement of fluids in the micro scale. Microfluidic chips were designed on autoCAD which were to be used to produce silicon wafer master moulds. Unfortunately these were not created in time.

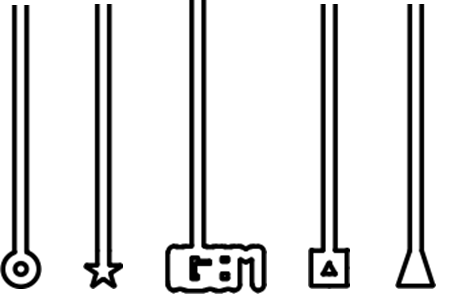

The idea was to use directed flow within the microfluidic wafer to physically manoeuvre L-form cells into designed chambers of different shapes, such as those shown in figure 1. The membranes of the L-forms were to be stained with FM.595 and in this way we would be able to visualise whether the L-forms were able to adopt different shapes.

Figure 1. The design of the chambers which L-forms would be forced into. The L-forms would potentially adopt the shape of the terminal part of the chambers.

Modelling

To show the flexibility of the L-forms we have planned to trap them in a microfluidics chamber whose shape differs from that of a normal L-form e.g. a star, square or triangle.

Before we began to design the experiments, we wished to illustrate the process which we predict to occur inside of the terminal chamber as the cell grows. For this, we constructed a model of the predicted cell behaviour as it grows inside a square. This model was based on the knowledge that we have about the processes inside the cell which are involved in membrane synthesis and growth. We would like to thank Dr. David Swailes from the School of Mechanical Engineering at Newcastle University for the great amount of help with the mathematical aspects of this modelling.

For the purposes of this study, the complexity of a growing cell inside a confined space can be broken down to simpler models of the system at two phases. The first phase is a constantly growing cell, this phase is followed by the cell gradually adopting the shape of the boundaries.

The full description of the model can be found on this page.

This model can be improved by conducting experiments which would allow us to find accurate parameters such as for the rate of membrane synthesis and maximum membrane torsion. Freeing the model of a few assumptions would also be beneficial. For example if the effects of nutrient depletion were found, and if the maximum size the cell could grow to before dividing was derived, then these could be worked into the model. The model could also be expanded in terms of factoring in the bending energy of the membrane in a particular shape. This would allow us to compare the models of the cells adopting different shapes and to evaluate which shape would me more readily assumed.

It would also be interesting to see whether the state of the cell (i.e. L- or rod form) before it enters the chamber has any bearing on the way it fills the space.

References

Trachtenberg S. (1998) Mollicutes-wall-less bacteria with internal cytoskeletons. Journal of Structural Biology. 124, 244-256.

Errington J. (2013) L-form bacteria, cell walls and the origins of life. Open Biology, 3, 120143

"

"