Team:Edinburgh/Modeling

From 2013.igem.org

Motivation

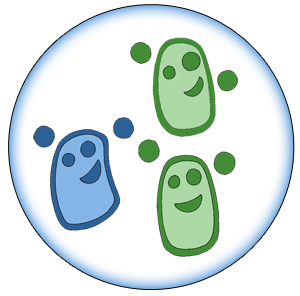

Synthetic biologists often design genetic circuitry in isolation, taking little consideration of the host cells in which these circuits will operate. They tend to create specific, local models which don't capture the circuits' interactions with other host components. This is an oversimplification because the circuit genes and products interact with the host cell in various ways:

- The circuit is dependent upon the resources and machinery available to the cell – so if resources are scarce, this is likely to hinder the circuit transcription and translation.

- The cell needs to replicate, translate and transcribe the additional genes inserted into it and this draws upon the host’s resources which could otherwise be used for metabolism and growth. As a result, if the circuit is long or the genes on it are overexpressed, this can slow down the growth of the host cell.

- The gene products of the circuit might interact with the cell metabolism in an undesirable manner. For example, they might be toxic to the host. Alternatively, some of the host's metabolic enzymes might inhibit the circuit's production rate; an obviously unwanted side effect.

Failing to take account of those interactions and their consequences at the design stage can cause designs to fail or be sub-optimal.

Goals

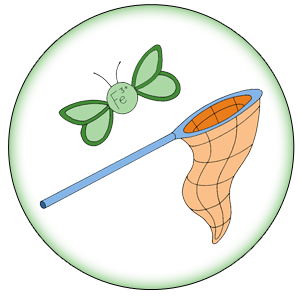

With this in mind, we decided to introduce the concept of whole-cell modeling to iGEM: picturing the entire cell and capturing key factors of its life cycle and metabolism. A very abstract, high-level cell "template" could be made thus, or instead a very detailed, richly-informative model, depending on the data available and on the specific application.

Our whole-cell model is founded upon a modular platform that serves as a cellular task manager; each process that takes place within the cell becomes simply an independent plugin, a function that is inserted into the platform and reads the various available cellular resources, then changes them appropriately as a result. The task manager cycles through all the processes, then updates the resources and takes a small step forward in time. This way, we simulate the interactions between the various cellular processes, be they native or introduced; hopefully we gain insight as to how the artificial circuit operates in the wider context of the cell. This information aids the development of better-informed designs, which have a symbiotic rather than a parasitic relationship with their host.

Better yet than a living breathing computer cell is a computer cell that is accessible to everyone, despite its turbid programmatic depths. The modular platform at this model's core allows for easy mix-and-match of prepared modules (a.k.a. cellular processes) that are defined by the "black box" principle: the platform doesn't care about the module's internal workings; all it needs to know is the modified cell state (e.g. substance amounts, environment variables, resource availability, etc.) that each module produces in a given amount of time.

This idea can be extended to make the whole-cell model itself into a module which can run on a superplatform. It would be possible to choose the specific whole cell model that is required from a library of models (each depicting a different cell species or strain), or to create and program your own one. It may also be possible to specify some options, like turning on and off some features of the whole cell model or scaling the accuracy of the simulation, thus customizing it to be more coarse- or fine-grained according to tastes and inner beliefs.

Keeping our eyes trained on this ambitious goal we set off on an auspicious journey to explore this idea and make a first few steps towards implementing it.

|

| | | |

|

| This iGEM team has been funded by the MSD Scottish Life Sciences Fund. The opinions expressed by this iGEM team are those of the team members and do not necessarily represent those of MSD | |||||

"

"