Team:SydneyUni Australia/Project/Background

From 2013.igem.org

Botany

There is evidence of settlement by the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eora Eora people] in Sydney for many thousands of years. Many household English words are inherited from their language, including dingo, wombat, waratah, wallaby, etc. The best explanation for this is that when Captain Cook initially landed on the continent of Australia, way back in 1770 at Botany Bay, the Eora people were first he met. Thus Botany Bay is not only a significant historical landmark, but represents a collision of worlds, languages, cultures, and relationships to the environment.

Today, Botany is part of the modern city of Sydney - it’s a suburb with schools, supermarkets, churches, and so on. It’s also been the site of an Orica (previously ICI Australia) manufacturing plant since the [http://www.oricabotanytransformation.com/?page=25 1940’s]. During this period of industrial activity in a period of relatively absent environmental awareness and regulation, there has been extensive chemical pollution of the Botany Industrial Park site, leading to contamination of the groundwater. In 1998, a plume of DCA (1,2-dichloroethane) was discovered in the groundwater. Since then the contamination has been tracked, treated, modelled, debated, and more. Residents are [http://www.water.nsw.gov.au/Water-management/Water-quality/Groundwater/Botany-Sand-Beds-aquifer/Botany-Sands-Aquifer/default.aspx banned] from using the water for drinking, washing, watering the garden - anything.

The pollution at Botany Bay is not only a hassle for local residents or a justification for Orica’s new [http://www.oricabotanytransformation.com/?page=30 Groundwater Treatment Plant]. It is a symbol of a people out of touch with their environment.

Chlorinated Hydrocarbons

“These chemicals are soluble, volatile and stable, which are useful properties and they have utility in society, so we do not want to stop using them, but we need to handle them better and find better ways to clean them up.” - [http://www.sustainabilitymatters.net.au/articles/61838-Matchmaking-bacteria-on-contaminated-sites Mike Manefield]

The literature on the toxic and carcinogenic status of chlorinated hydrocarbons is confusing and sometimes contradictory (eg, see [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20146755 Mattes et al, 2010]), but it is generally accepted that they're pretty nasty, should be handled with care, and if possible removed from our groundwater.

Conventional Treatment

Pumping and heat-treating

Orica is responsible for managing the groundwater contamination at the Botany Industrial Park. The aquifer water is pumped to the groundwater treatment plant, where the volatile pollutants are removed by air-stripping, then thermal oxidation, and by deliberate positioning of the pumps around the region they can effectively contain the contaminated groundwater and prevent it from leaking into Botany Bay. The Groundwater Treatment Plant cost around $170 million to build and pumps around 6ML of water every day. The [http://www.oricabotanytransformation.com/?page=30 Groundwater Treatment Plant] is designed to last for 30 years. With the [http://www.smh.com.au/news/environment/botany-cleanup-may-take-a-century/2008/11/26/1227491636580.html current estimates] of contaminant removal, the groundwater will not be clean by then.

Bioaugmentation and biostimulation

Bioaugmentation means adding known pollutant-degraders to the environment. Biostimulation means adding energy or nutrients that may assist indigenous bacteria to degrade pollutants. Some [http://www.oricabotanytransformation.com/files/pdf/Reports/GW/CSM/CSM2010_FILES/107623162_001_R_Rev0_CSM%2020110131.pdf limited success] has been met with both methods in Botany Bay, with the main difficulty of scaling-up any treatment to a size comparable with the contamination.

Our Project

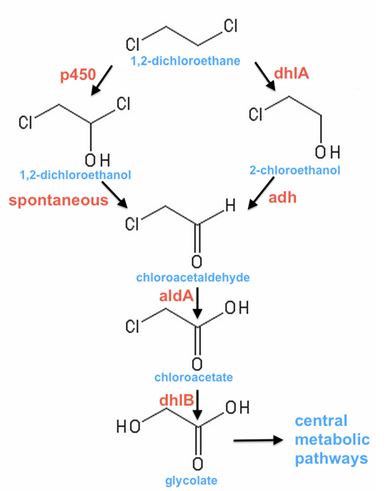

There are only two paths of aerobic DCA degradation, as in the picture below.

- One begins with oxidation, and has been documented in Pseudomonas spp. [strains DE2 (Stucki et al. 1983) and DCA1 (Hage and Hartmans, 1999)], as well as toluene degraders [Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 (McClay, 1996)] and also a DCA-degrader that our supervisor Nick Coleman, isolated a decade ago [Polaromonas JS666 (Nishino et al, 2013)].

- The other pathway begins by hydrolytic removal of a Cl- ion, eg, Xanthobacter autotrophicus GJ10 (Janssen, 1994), A. aquaticus strains AD25 and AD27 (van den Wijngaard et al., 1992) and some South African strains isolated from contaminated waste-water (Govender & Pillay, 2011). Jake Munro and Elissa Liew from the Coleman lab have isolated and characterised several hydrolytic DCA degraders from the Botany site.

Neither of these pathways have been built from scratch.

- This is true in the sense that people have learned about DCA-degradation by taking the pathway apart, ie, by cloning a single gene and testing it out in a foreign host (usually E. Coli) and seeing whether it degrades a substrate or set of substrates. Part of the philosophy behind Synthetic Biology is learning by building, which makes our project a neat way to build on extensive research characterising individual genes.

- It is also true in the sense that pollutant-degrading bacteria of interest can learn to degrade xenobiotics by piecing together genes from vastly different origins, and enzymes with activity on very different substrates, often by horizontal gene transfer ([http://www.ce.gatech.edu/people/faculty/671/overview Jim Spain] gave a talk at our school describing this process). Our project has involved a similar process of appropriating genes from different origins, but using online databases of sequences rather than the genepool of a particular microcosm.

Goals

- Construct and compare two of the proposed pathways of DCA biodegradation.

- Characterise the components of the DCA-degradation pathway for admission into the Registry of Standard Parts.

References

- Govender, A., & Pillay, B. (2011). Characterization of 1, 2-dichloroethane(DCA) degrading bacteria isolated from South African waste water. African Journal of Biotechnology, 10(55), 11567-11573.

- Hage, J. C., & Hartmans, S. (1999). Monooxygenase-mediated 1, 2-dichloroethane degradation by Pseudomonas sp. strain DCA1. Applied and environmental microbiology, 65(6), 2466-2470.

- Janssen, D. B., Pries, F., & Van der Ploeg, J. R. (1994). Genetics and biochemistry of dehalogenating enzymes. Annual Reviews in Microbiology, 48(1), 163-191.

- McClay, K., Fox, B. G., & Steffan, R. J. (1996). Chloroform mineralization by toluene-oxidizing bacteria. Applied and environmental microbiology, 62(8), 2716-2722.

- Nishino, S. F., Shin, K. A., Gossett, J. M., & Spain, J. C. (2013). Cytochrome P450 Initiates Degradation of cis-Dichloroethene by Polaromonas sp. Strain JS666. Applied and environmental microbiology, 79(7), 2263-2272.

- Stucki, G., Krebser, U., & Leisinger, T. (1983). Bacterial growth on 1, 2-dichloroethane. Experientia, 39(11), 1271-1273.

- Van den Wijngaard, A. J., Van der Kamp, K. W., Van der Ploeg, J., Pries, F., Kazemier, B., & Janssen, D. B. (1992). Degradation of 1, 2-dichloroethane by Ancylobacter aquaticus and other facultative methylotrophs. Applied and environmental microbiology, 58(3), 976-983.

"

"