Team:Calgary Entrepreneurial/Project/Technology/

From 2013.igem.org

FREDsense's website works best with Javascript enabled, especially on mobile devices. Please enable Javascript for optimal viewing.

Developing our Technology

We are pioneering a live-cell Field-Ready Electrochemical Detection system for toxins present in our environment. Initially, we are focusing on detecting general toxins in oil sands environments, however the immense flexibility our system provides significant opportunities to expand into sensors for almost any compound of interest. With a quick and robust output, our technology offers many advantages over existing biosensor technologies.

Overview

In response to the need for rapid and more on-site technologies to monitor toxins in the oil and gas sector, FREDsense is pioneering a novel biosensor technology. Our first generation product is designed to detect a variety of oil and gas related contaminants in water samples. The system will be more rapid and more portable than current analytical technologies.

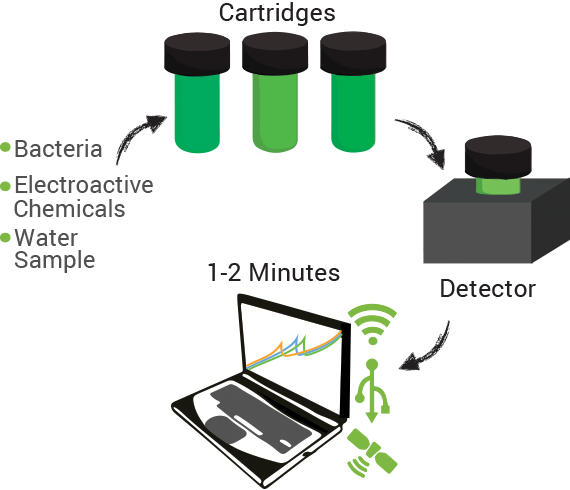

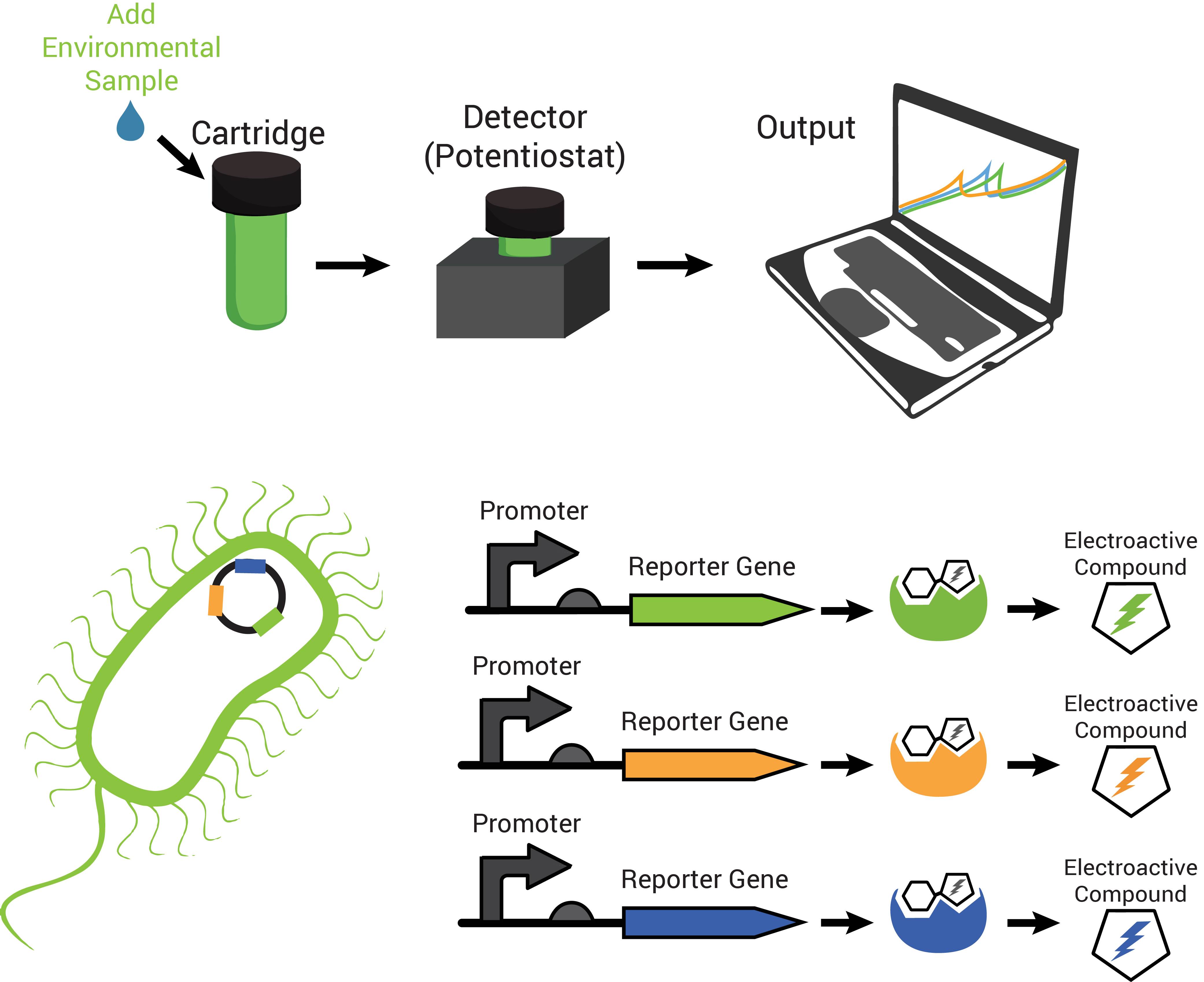

The technology contains two components: disposable cartridges that will hold the sample and “sensing” bacteria, and the detector (Figure 1). The cartridges will contain microorganisms designed to demonstrate detection of toxins by producing enzymes capable of changing analyte compounds so that they can be detected electrochemically (Figure 2). The detector device contains all of the circuitry necessary to read the electrochemical output from the bacterial strain and transmit it to a computer.

Data can be collected through a variety of inputs whether direct connections on site (USB) or wirelessly through cellular and existing data networks on-site. Additionally, measurements can be linked to specific geospatial positions using GPS technology. Bringing it all together we envision our system integrating within current data management systems already in use in the oil sands in addition to providing our own cloud computing based system.

To date, we have generated a microbial strain that is able to detect three relevant oil sands toxins: naphthenic acids, carbazole, and dibenzothiophene. We have demonstrated the output of the detector as being able to alter analyte compounds so that they may be detected electrochemically. Furthermore we are working to demonstrate that we can detect simultaneously active output signals, where more than one compound can be detected at a time. We currently have a proof-of-concept technology for detecting oil sands toxins.

As we are refining the techniques to optimally detect toxins with the microbial strain, we are developing a prototype of the system that will be sold commercially and will be ultimately be used by clients for field tests. On this front we are working closely with manufacturers to design our final product.

Detailed Description of the Technology

Sensing Microorganism:

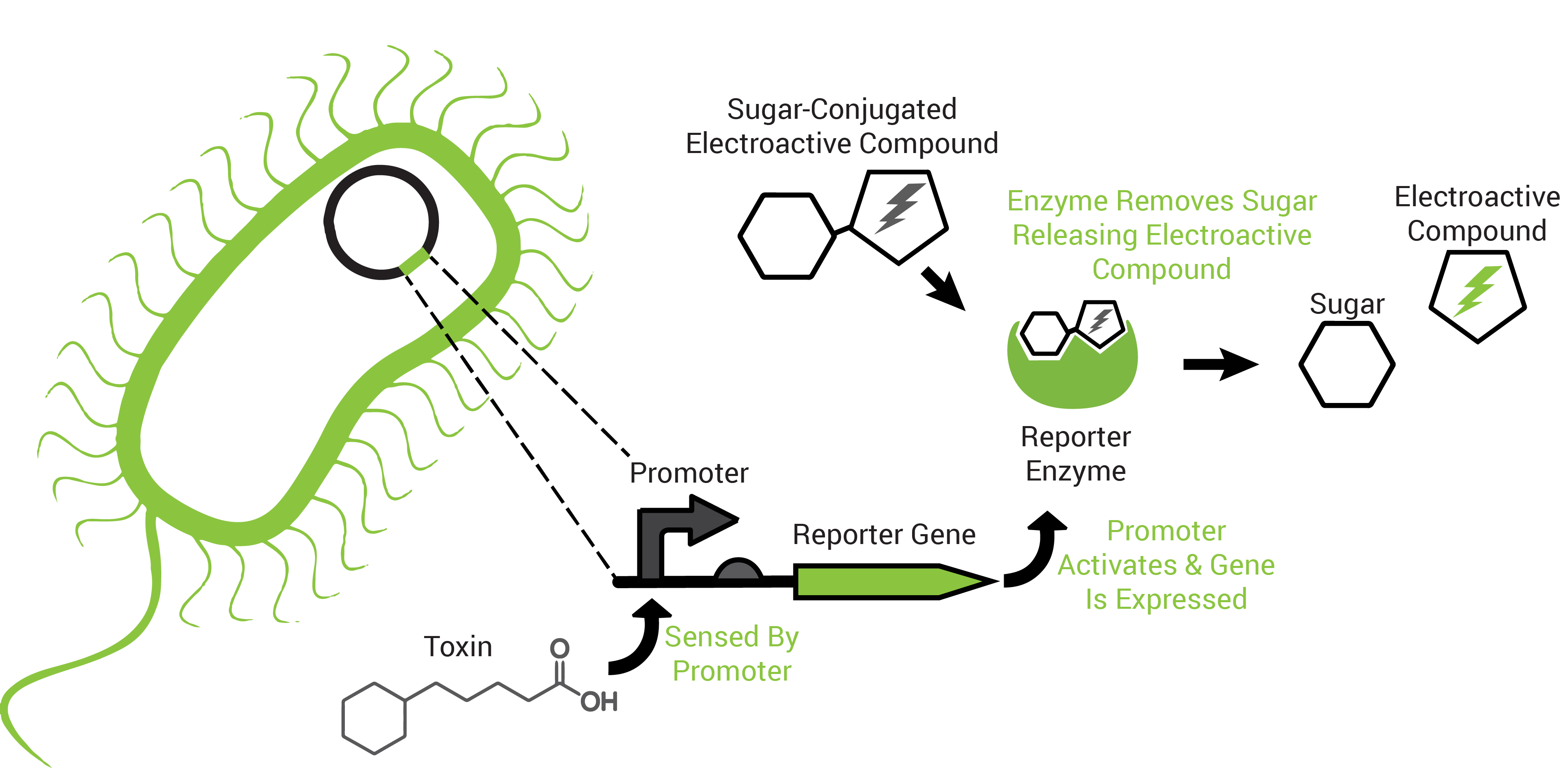

To obtain an organism that may respond to petroleum toxins, we performed a transposon screen. This biological screen inserts the genetic sequence of a reporting protein (the enzyme β-galactosidase) into random locations of the test organism's DNA. The purpose is to put the reporter in a region that the host organism uses to survive the toxicity of petroleum toxins because this way it would "tell us" that those chemicals are present (Figure 2).

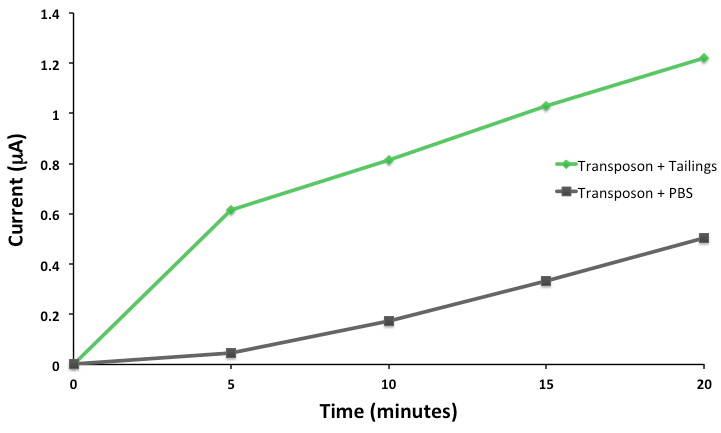

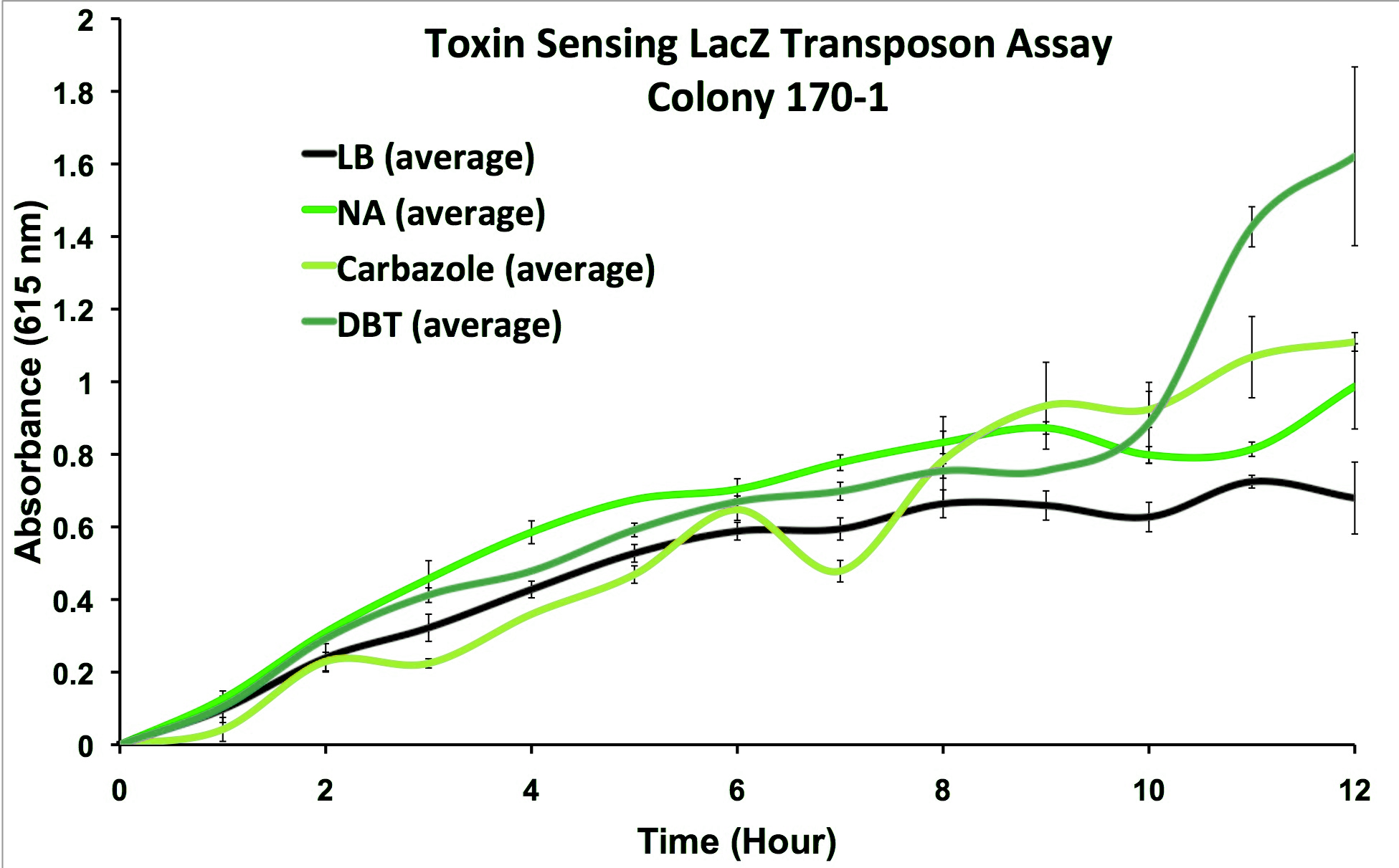

We performed the transposon screen with the organism Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5: a native tailings pond bacteria shown to degrade oil sands toxins. From this screen strains which responded to general oil sands toxins (sulfur-heterocycles, nitrogen heterocycles, and naphthenic acids) were kept for further analysis. We characterized these strains and selected from the original responders, strains that reacted to oil sands toxins but not general hydrocarbon compounds and stress agents (Figure 3).

This response consists of production of a reporter enzyme capable of cleaving a substrate which could then give an electrochemical response. Further testing on one strain using tailings pond samples showed a higher than baseline response, and the organism was capable of survival in the toxic substrate (Figure 4).

Future directions for strain development include identifying and characterizing the genetic sequence of the sensing elements.

Electrochemical Enzymatic Reporting System:

The reporter proteins utilized by FREDsense are part of a class of enzymes known as hydrolases. Characteristic of these enzymes is recognition and cleavage of their target structure from another compound that it is bound to. An example of this is the protein β-galactosidase (encoded by the gene lacZ). β-galactosidase recognizes and cleaves galactose bound to other compounds and has traditionally been used for colorimetric reactions in biological science study. For our purposes we are using galactose bound to the electroactive compound or analyte CPR-β-D-galactopyranoside (CPRG). Freeing the CPR unmasks its charge, permitting electrochemical detection of it in solution by cyclic voltammetry.

Also characteristic of many hydrolases is the specific recognition of their substrates. A cell can produce more than one hydrolase by independent stimuli and those hydrolases can target and cleave their substrates in solution. Many electroactive compounds (analytes) have different oxidation potentials and conveniently can be bound to substrates of the hydrolases. Therefore, different electroactive substrate-bound compounds could be freed from their substrate by the hydrolase that can recognize them specifically, to elicit independent responses that could be observed electrochemically. Analagous to this is the ability to simultaneously observe independently labelled blue, green and red fluorescent particles in a cell.

Due to availability and differing oxidation potentials reported in the literature, we chose chlorophenol red (CPR), para-diphenol (PDP), and para-nitrophenol (PNP) for the analytes we would use. Since we were able to confirm that they could be independently detected (Figure 4a), we went on to observe whether hydrolases from living cells could cleave substrate-bound versions of these compounds. The hydrolases that we tested were put into standardized plasmid DNA expression systems in laboratory Escherichia coli, under control of an inducible promoter for testing. The graphs in Figure 4b, demonstrate that the hydrolases β-galactosidase (lacZ gene), β-D-glucoside glucohydrolase (bglX gene), and β-glucuronidase (uidA gene) could cleave their respective substrates CPR-β-D-galactopyranoside (CPRG), PDP-β-D-glucopyranoside (PDPG), and PNP-β-D-glucuronide (PNPG) to produce detectable analytes. With enzymes capable of cleaving the substrate to release analytes with independently observable peaks, we have produced a system with the potential to multiplex output signals.

We need the multiplexing graph. Might even be able to put some of the ones from the patenting experiments in here instead, since some of them do look better. We need more intro slides as well.

Hardware, Software, and Prototype Design:

Before the FREDsense biosensor can become a product, we needed to begin characterization of the live cell reporting system and design a prototype of how the device would work. We address progress towards prototype design and manufacture in more detail in the Operations section. please insert link to Operations section, or we don't mention this work here at all and move it to manufacture.

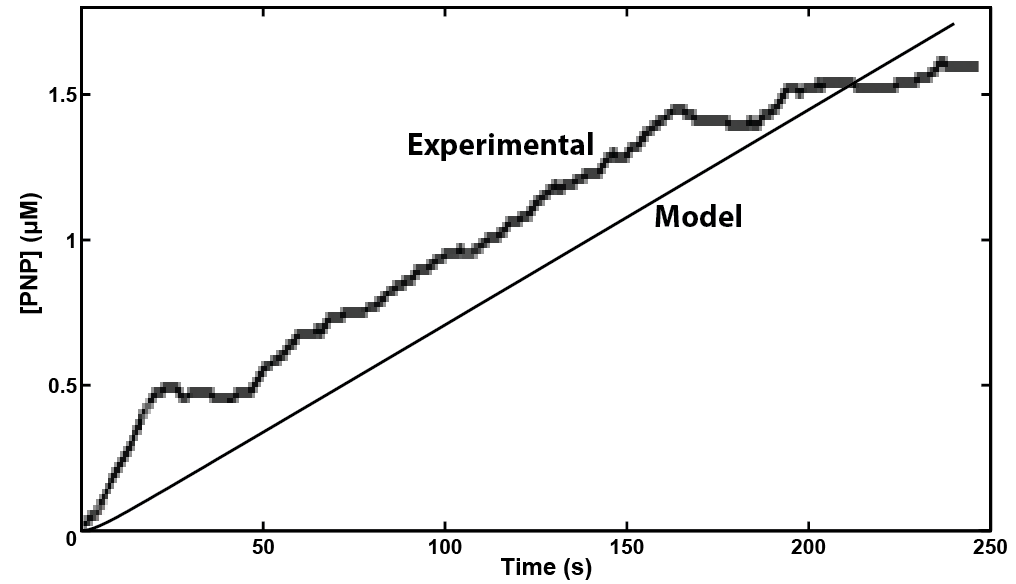

In making a live cell biosensor, we need to characterize the rate of response in which an enzyme will work to produce the analyte. A kinetic model was built for the activity of the enzyme β-glucuronidase uidA in MatLab, predicting that a response could be detected within 4 minutes of adding the substrate to the enzyme when read electrochemically. This experiment was then performed with live cell induction of β-glucuronidase expression. The results were consistent with the model's prediction, informing our design of the protocol for the biosensor. As we characterize the sensing micro-organism more fully, we will use predictive modeling of its behavior to develop quantitative interpretation of toxin level in solution.

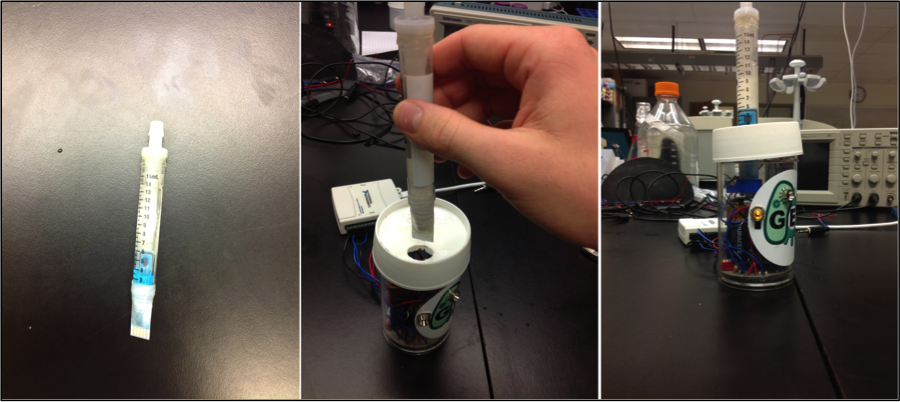

To take our live cell detector into the field, we needed to convert equipment that would normally fill a lab bench to a portable, user-friendly device. We began this process with the design and development of an inexpensive, small, and portable potentiostat. Required circuitry being printed onto a small circuit board. Samples would be loaded through a one-way valve into a sample cartridge (adapted 15mL culture tube) containing the cells, electrochemical substrates, and other reagents required to produce the electrochemical response. The sample cartridge also has a disposable electrode accessible to the sample. The cartridge/electrode plugs into a slot, connecting it to the circuitboard and power source. The device is also equipped with LED lights to indicate what step of the analysis process is currently running and indicate when it has completed.

While more sophisticated potentiostats function well for our detection, we will ultimately need a small portable version that functions well for our needs. We developed a custom software package within the MatLab platform to interpret and display the data obtained from electrochemical measurement. Ultimately we will want the Graphical User Interface (GUI) to convert the amplitude of electrochemical response to the concentration of chemical being sampled.

Technical Implementation Plan

In order to realize our first generation product, there are several key steps that need to be taken on the research and development front. As such, we have created a detailed Implementation plan describing these necessary milestones. A condensed version can be seen below. Here we list the major technical milestones that need to be completed. These points are listed in order of priority with the earliest described experiments being most critical in evaluating the commercial potential of our technology. As such, the order represents the relative risk of each experiment, with the most high-risk experiments first, where failure to achieve good results could significantly impact the time and cost estimates for the research and development.

- Final characterization of our first generation sensing organism.

- Transferring our electrochemical system into P. fluorescencs.

- Transitioning our first product into the final prototyping stages.

- Further screening for future generation products.

- Further multiplexing of our electrochemical system.

Responding to Technological Change

The current technology has been carefully designed in order to easily facilitate the production of next generation products. FREDsense’s unique sensing platform is easily adaptable to monitor a plethora of different compounds of interest using different engineered bacterial strains. Second generation products are being developed including detector products specific to unique classes of chemicals including naphthenic acids and hydrocarbons. As these are specific compounds of interest for many oil sands-related processes, detectors capable of monitoring them with specificity are sought-after. These detectors will make use of FREDsense’s novel generation one sensing platform coupled with newly developed bacterial strains. Being able to directly build upon the existing platform will help ensure FREDsense’s new products can be designed quickly and efficiently so as to have a quicker entry to market than generation one products.

With the introduction of more specific and diverse sensors, this will lead the way for multiple-output detector systems. These will include detectors that can monitor multiple different classes of compounds such as combinations of naphthenic acids, hydrocarbons and general toxins simultaneously. As many locations would require monitoring of a variety of compounds of interest at one sampling time, these second generation sensors will allow one water sample to be taken in order to monitor that sample for several toxins. This will allow for quicker sample extraction and faster results. Again, these products will make use of the generation one electrochemical sensing platform with new engineered bacterial strains.

As with generation one, all later generation products will include integrated controls as well as the speed and reliability of the generation one sensing platform. The modular design of FREDsense’s technology will allow the company to adapt quickly and easily to changes in the regulatory landscape in the oil sands market as well as expand into different markets. This will allow FREDsense to expand the breadth of its detection products without investing significant resources into research and development.

Regulatory Hurdles

Biotechnology products in Canada are regulated by three federal agencies: Health Canada for foods, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) for seeds and livestock feed, and Environment Canada for new substances intended for environmental release. Our product thus falls under regulation set out by the later. This regulation falls under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (jointly administered by Environment Canada and Health Canada). Environmental Technology Verification is also required for our technology to be used in this industry. Risk is assessed based on relative toxicity as well as relative amount of exposure to the environment. Specific products are assessed on a one-to-one basis through a dialogue with Environment Canada and Health Canada.

Safety Approval from CEPA

With respect to safety, we need to make our organism approved according to the “New Substances Notification Regulations (Organisms)", SOR/2005-248, which is a part of the Canadian Environmental Protection Agency (CEPA) act. Due to our organism being an innocuous, ubiquitous, microbe that is indigenous to soil, we anticipate that performing the experiments required for approval will eventually lead to permission to mass produce this organism. In spite of this, to obtain agency approval we are required to perform extensive tests on our organism and have adequate protocols to prevent accidental release of our organism.

The most important characterizations that we need to disclose include:

- Mechanisms to detect our organism in the environment, in the incidence of escape. This includes genus, species, strain features, and the genetic changes we induced to enable reporting of our sensor. The necessity for these characterizations are already in line with our need for further technological development of our micro-organism sensor, and we hope to have this complete by July 2014.

- Characterization of environmental impact and toxicological studies. These characterizations are to disclose how our strain could impact the local ecosystem, terrestrial and aquatic organisms: ie. is it dangerous? To perform these studies we will perform standard toxicology experiments in which it is cultured in the presence of model test organisms. We will also co-culture the strain with indigenous aquatic and soil micro-organisms to determine if gene transfer occurs from our strain and if so, at what rate. With regards to the interest of human health, we will provide the information necessary to distinguish our organism from known pathogens. We hope to have these experiments complete by December 2014.

- Development of protocols for dealing with containment upon accidental release. Because our strain will be mass produced and packaged for field use, containment is very important. We will likely use established level 1 biohazard clean-up protocols should our system breach. The protocols will be fully developed when we know the details of how, where, and who will be contracted to manufacture the organism. The device that will be taken to the field is designed to keep the microbe contained within it, whereby a cytotoxic chemical is released to the microbe upon completion of the assay. This chemical compartment will be built into the cartridges and release will be initiated after the assay is run to completion. The final mechanisms for this will be developed as we approach the product development phase where the prototype is finalized.

The deadline for submitting this information for approval is 120 days prior to when we plan to start using the organism. Being well organised and using an innocuous genetically modified organism, we do not expect delay from this regulatory approval.

Standards Approval

In order to be able to monitor toxins in the oil sands industry as part of government mandated regulation, we require accreditation from the Canadian Association for Laboratory Accreditation (CALA). Specifically, we would need petroleum accreditation for testing water and soil toxicology. In order to receive this accreditation, in-house toxicology tests would need to be performed and compared to CALA standards. Upon completion of these, CALA-certified assessors would need to visit the site in order to repeat these tests. Any discrepancies would need to be corrected within three months, prior to a re-test verification. As the CALA criteria are extremely strict, the accreditation process can be time-consuming. As such, we will need to consider alternative sources of revenue should this process encounter significant delays.

"

"