Team:Leeds/Project

From 2013.igem.org

|

Our ProjectWhat is MicroBeagle I hear you cry?Well, MicroBeagle is an E.coli cell that has been modified so that it can help “hunt down” pathogens. Just like a Beagle, the hunting dog, searches for, finds, and indicates the presence of rabbits and hares, our MircoBeagle finds and points to pathogens, detecting them through physical binding, and lighting up to indicate their presence! By utilising the Cpx pathway, which responds to membrane stress (which we hypothesize would be induced by the binding event) and GFP (as a reporter) we hope to create a new biosensor that ultimately will give diagnostic results that can be seen with the naked eye.

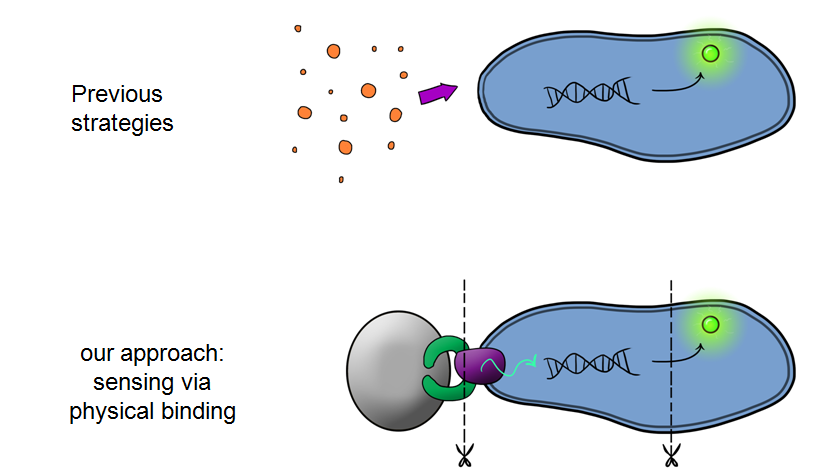

Our MicroBeagle project is laying groundwork towards the development of a modular, general platform for pathogen detection. What makes Leeds iGEM's MicroBeagle distinctive to previous strategies used for analyte detection within iGEM is that we use physical binding as our detection mode, versus sensing of soluble analytes as has been explored in previous iGEM projects. A physical binding detection mode should be well suited to assaying for a wide range of pathogen targets, as tailored target-binding proteins or peptides can be displayed from the cell surface, allowing specific binding to the pathogen of interest.

Why is the MircoBeagle a useful device?There could be many different possible uses for our device, as the pathogen detection mechanism we are using is modular and can easily be tailored to individual needs. This is achieved by swapping out the gene coding the cell surface-displayed binding domain to suit your needs. We envision the MircoBeagle being used for testing blood samples, detection of heavy metals and, in the application that is our main inspiration, detection of pathogens in water samples.

Why Water Testing is so important Detecting pathogens in water is a really important application as 3.4 million people a year die from water related diseases[http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/takingcharge.html [1]],[http://water.org/water-crisis/water-facts/water/ [2]].

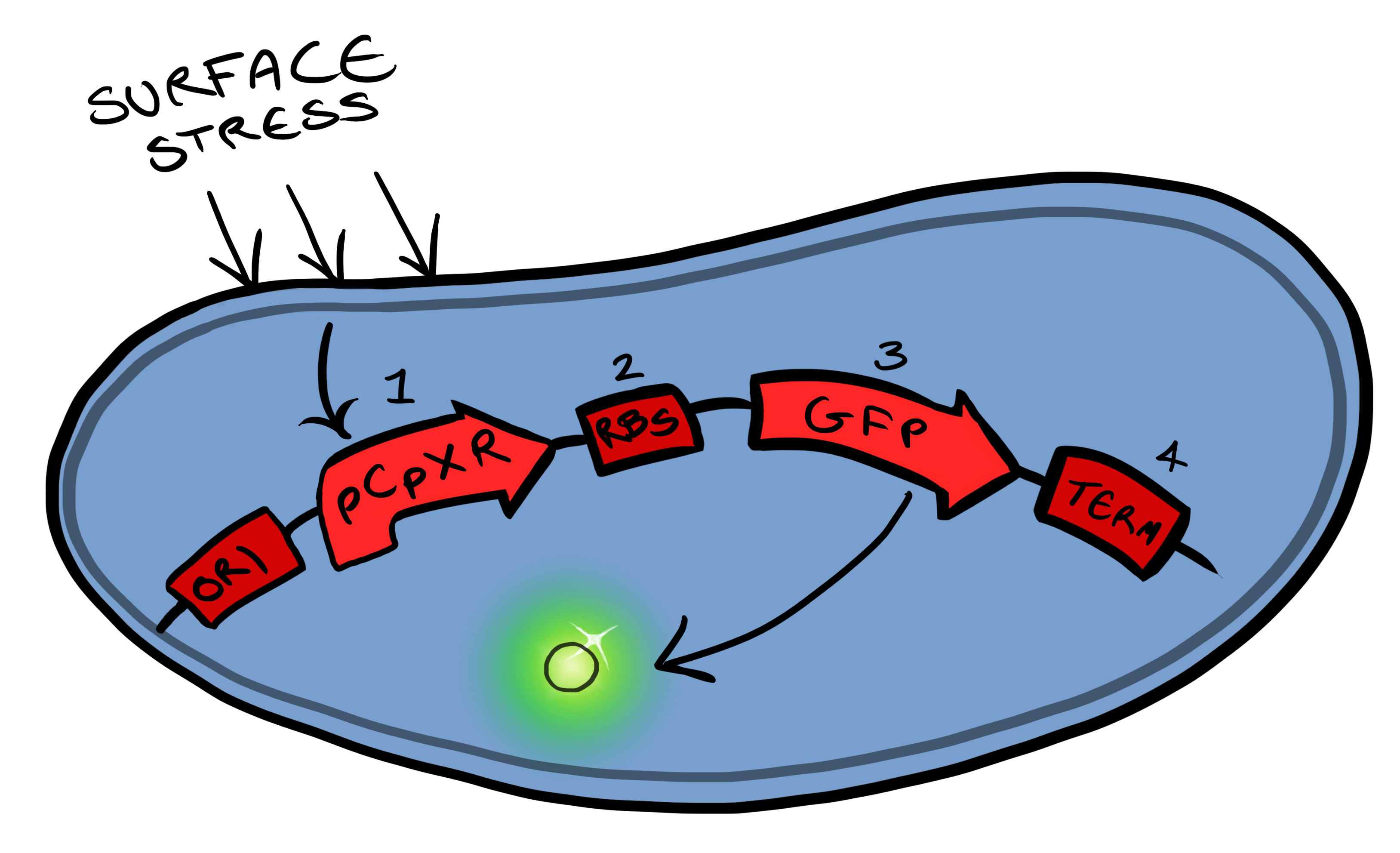

Below is a summary of our Device development strategy...Phase IWe split our project into self-contained phases, to help better organise ourselves, but also lay out a road map for our own future work within iGEM and beyond. Our two devices include a device for activating a reporter in response to membrane stress (Device 1) and a device for binding to a physical target at the cell surface and thereby activate the membrane-stress-reporter (Device 2). Device 1 Device 1 is a very simple modification of the pCpxR promoter in E. coli to produce a fluorescent reporter when the cell is under membrane stress. Activation of Cpx pathways in response to solid surface interactions was first reported by [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11830644 Otto & Silhaevy 2001] in which hydrophobically treated glass beads were used to induce membrane stress. Given that the promoter pCpxR was specifically shown to be activated by this interaction, our hope is that, in initial stages of MicroBeagle development, this promoter can respond to a wide variety of physical binding interactions when these are specifically designed for target surfaces. pCpxR is present in the registry of standard biological parts, examined previously by [http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K339007 Calgary 2010] and [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K135001?title=Part:BBa_K135001 BCCS-Bristol 2008]. In our MicroBeagle work, we aim to further explore and characterize this promoter, and investigate for the first time the utility of this promoter in generating a reporting signal when specifically coupled with a designed cell surface-solid target binding interaction. We characterized our Device 1, pCpxR-GFP, by testing fluorescence generation vs a variety of potential membrane-stress-inducing environments, including various concentrations of a detergent (triton X-100) and the presence of various solid particles.

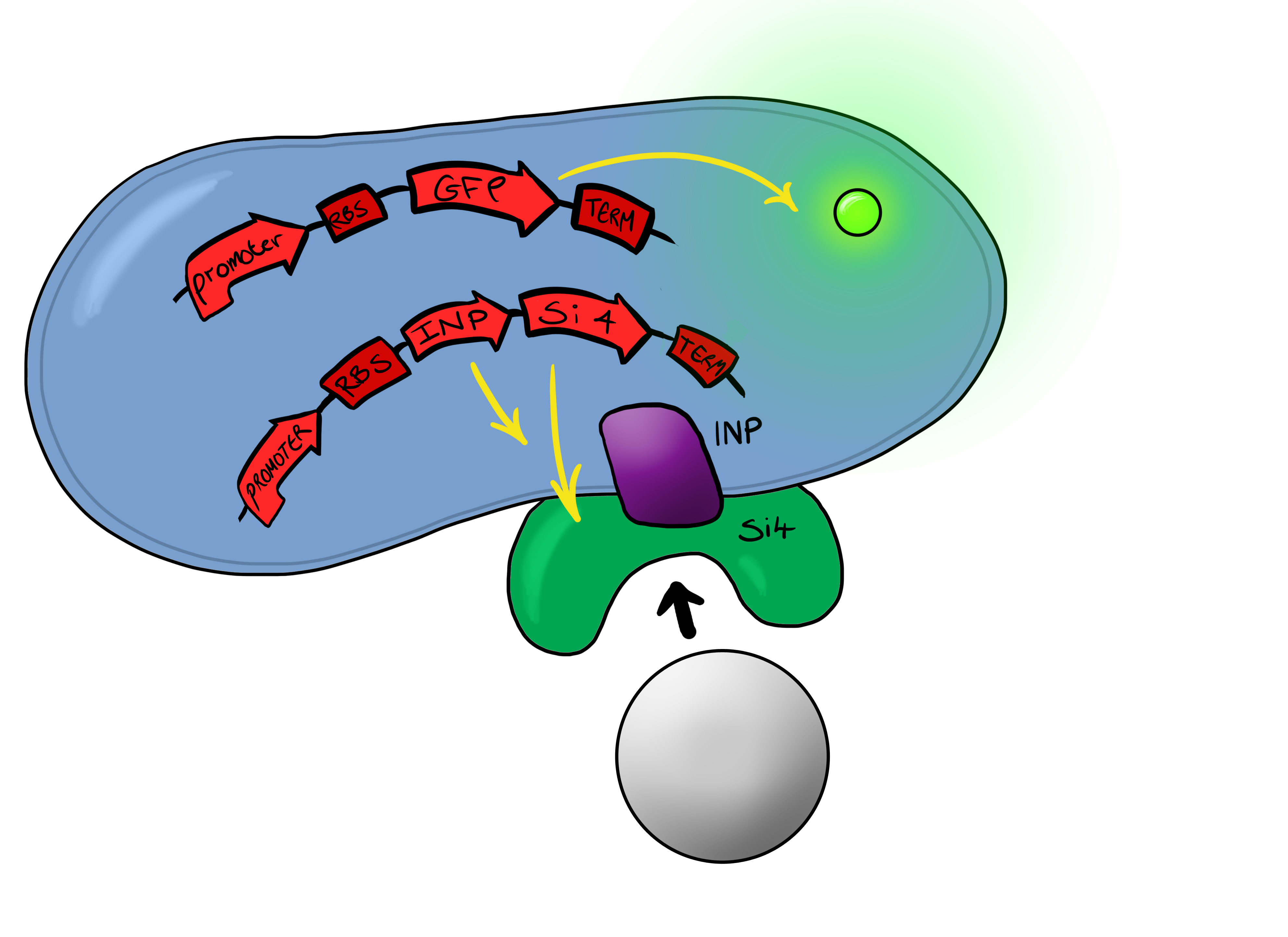

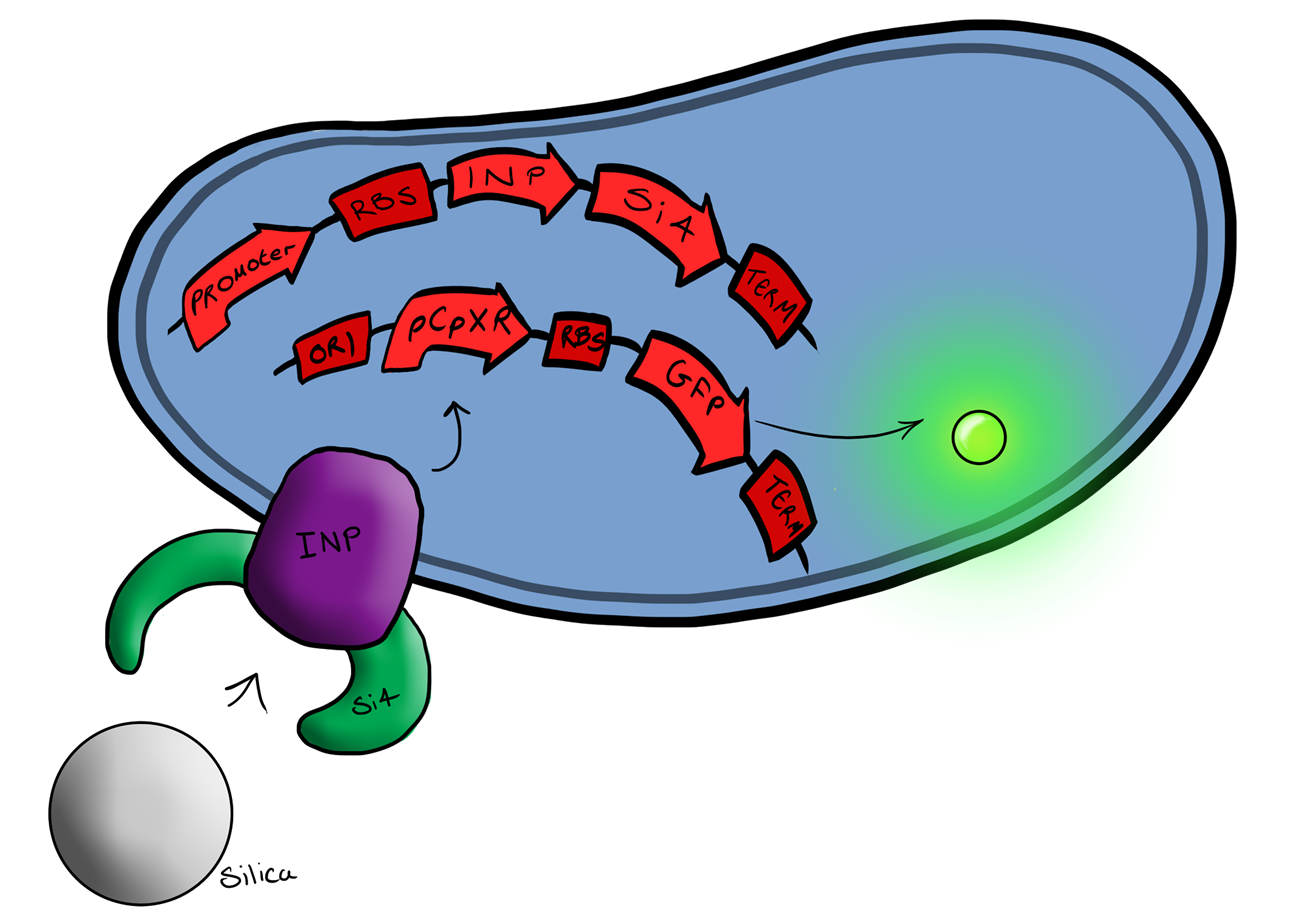

Si4 Binding PeptideOur second device of interest ("Device 2", described below) utilizes, in addition to the pCpxR reporter system (above), a surface-displayed target-binding moiety for physical attachment to particles. Display of the target-binding moiety utilizes Ice Nucleation Protein (INP) to display an oligo-peptide of our choice on the outer-membrane of our E. coli. Initially this will be a peptide capable of binding silica beads, allowing us to create a non-toxic model system of pathogen detection for initial stages of device development. INP is a transmembrane protein that expresses any sequence that is placed on the C-terminus of its gene on the outer surface of the cell. Specifically, we utilized the INP display system developed by [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K811003?title=Part:BBa_K811003 UPenn 2012]. The silica binding domain we utilized, termed "Si4" was developed by [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asp/jnn/2002/00000002/00000001/art00015 Naik, Lawrence, Clarson, and Stone 2002]. This silica-binding polypeptide was discovered via phage display screening, and was also found to precipitate silica when reacted with silicic acid. This provided us with an additional route to test for the presence of Si4 on cell surfaces, i.e. via mineralization assays using silicic acid as a mineral precursor.

Phase IIPhase II takes the products of Phase I to the next level, and begins to look at integration of the INP-displayed Si4 binding peptide and Device 1 to give a new device; Device 2. Device 2 Device 2 brings together on the same plasmid the genes that code for (1) the CpxP promoter controlling GFP expression and (2) the INP-displayed Si4 binding domain. The effect of this is that when the Si4 binding domain binds to the silica target, surface stress propagated through the INP protein will activate the pCpxR promoter through the Cpx signaling pathway. This will cause GFP to be produced and thereby act as a visible signal that the 'pathogen' has been detected.

The Cpx PathwayThis project is highly dependent upon a naturally occuring pathway in E.Coli called the Cpx pathway. It is associated with the regulation of periplasmic membrane stress and the misfolding of surface proteins. We may need to fine tune MicroBeagle for different applications, so by understanding the way the pathway is regulated, we stand a better chance of controlling the exact response we want. This may be done in a number of ways, from utilisation of an off-switch regulator, CpxP, to additonal pathways used to create a bio-logic gate or even by optimisation of buffer solution.

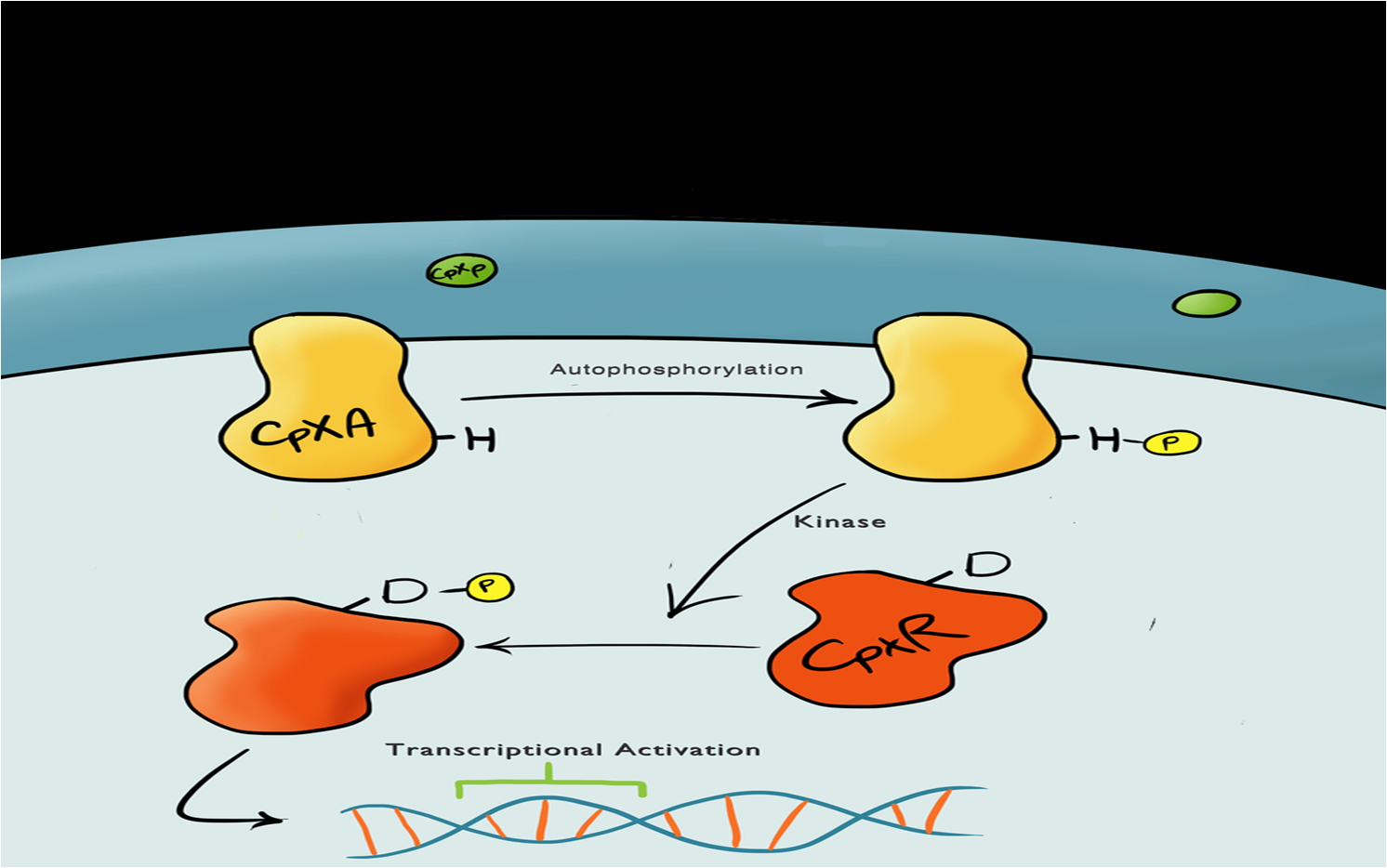

A brief explanation of the Cpx PathwayThe Cpx pathway responds to various membrane stresses; it is a two component signal transduction pathway. The first component is CpxA, an inner membrane protein which, when bound to CpxP (an inhibitor molecule), is inactive. When CpxP is unbound from CpxA, CpxA undergoes autophosphorylation. A kinase enzyme then phosphorylates CpxR, the second component in the pathway, which then binds to the pCpxR promoter and activates transcription. | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

"

"