Team:TU-Munich/Results/Software

From 2013.igem.org

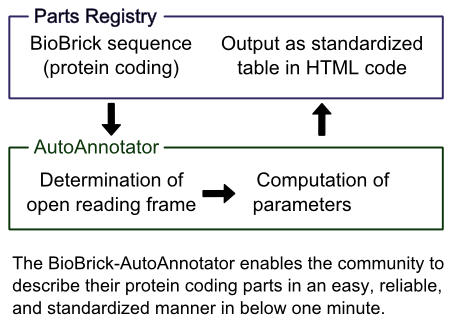

The AutoAnnotator

Introduction to the Idea behind our AutoAnnotator

The Parts Registry contains a wide range of interesting protein coding BioBricks, but there is no standardized way of presenting basic information about them. This is a real pity, because after the identification of the open reading frame a multitude of parameters of the protein can be computed automatically, e.g. its molecular mass, theoretical pI or codon quality for different organisms. We have developed a tool which is able to identify the open reading frame of a BioBrick, analyze the sequence and the encoded protein and export the results in a format that can easily be integrated into the part description (and the team wikis) as a single table.

This enables users to see basic information about the BioBrick at a quick glance in a standardized table, saving time, facilitating the comparison of BioBricks and improving the annotation of the parts. The AutoAnnotator can also be used for planning new Bricks, by quickly computing the relevant parameters in a single place rather than having to go to several different websites and gather the information together.

Try it out: The AutoAnnotator!

How to use the AutoAnnotator

- Enter the BioBrick number or the DNA sequence into the input window! For new parts the Registry database may have not been updated yet, so the AutoAnnotator can not get the sequence that way. In this case please enter the DNA sequence manually.

- Click the button!

- Check, that the automatically determined open reading frame (underlined in the DNA sequence) shown at the top of the table is correct!

- Enjoy the beauty of the table and the information in it!

- Copy the text in the box below the table into your part description or wiki to add the table to your site!

Please note, that there will be updates to the AutoAnnotator and that the predictions and alignments will improve as the data bases and the number of known structures grow, so it may be worth re-applying the AutoAnnotator, when looking at a BioBrick with an older version of the Annotator. Should the contents have changed, please replace the table.

Overview

The AutoAnnotator is a web-based tool compiling information about encoded proteins from the DNA sequence. It performs the following steps:

- Input: When entering a BioBrick number, the AutoAnnotator imports the nucleotide sequence directly from the Registry data base.

Alternatively a nucleotide sequence can be entered directly. This has to be used for new BioBricks, which aren't in the Registry yet, but can also be helpful for planning new BioBricks. - Finding the Open Reading Frame: In order to determine the Open Reading Frame (ORF) the algorithm first tries to determine what BioBrick assembly standard the BioBrick is in. If necessary (e.g. for an [http://parts.igem.org/Assembly_standard_25 RFC 25] Brick), nucleotides are added to the sequence. Then the ORF is determined by taking the first start codon and the first matching in-frame stop codon.

- Computation of Parameters: From the nucleotide sequence the codon usage for different organisms, i.e. whether the preferred codons are used or not (which contributes to the level of gene expression), is computed directly. Then after translating the DNA sequence into its amino acid sequence, several parameters of the encoded protein are determined, namely: the amino acid composition, the number of charged amino acids, the atomic composition, the molecular mass, the isoelectric point (pI) and the extinction coefficient of the protein. Also moving averages of the hydrophobicity and charge of the residues are calculated. For more information on each of these see below. Additionally the sequence is also compared to a list of sequence features, such as binding sites or cleavage sites.

- Alignments and Predictions: The amino acid sequence is also sent to the servers of [http://predictprotein.org PredictProtein.org], a site created and operated by the [http://rostlab.org Rost group], who kindly granted us access to their online resources. The servers provide alignments for the entered protein as well as predictions of the secondary structure, the solvent accessibility, the sub-cellular localization, the gene ontology and of transmembrane regions and disulfide bridges. Proteins, which are not among the over 30 million stored there, will be calculated and added, and should be ready in a matter of hours.

- Presentation of the Computed Data: The data is then put together into a concise, structured HTML table and displayed to the user. Sequence features and predictions are additionally shown in an optional plot as part of the table. Furthermore the code producing the table is displayed underneath it and so by a single copy&paste the table can be integrated into any wiki, part description or other website.

Import of BioBrick Sequences

Upon entering a BioBrick number the AutoAnnotator uses the [http://parts.igem.org/DAS_-_Distributed_Annotation_System Registry DAS] interface to load the nucleotide sequence from the data base of the Registry. To allow this cross-domain information request, which is blocked by most browsers for security reasons, an [http://james.padolsey.com/javascript/cross-domain-requests-with-jquery/ extension] to the .ajax() method in jQuery written by James Padolsey was used. This uses the [http://developer.yahoo.com/yql/ YQL] (Yahoo! Query Language), which is a service by Yahoo!, to redirect the request via their servers, in this way solving the security issues and allowing the Annotator to read the information from the Registry.

For newer BioBricks the Registry database (i.e. the DAS interface) may not have updated the sequence yet, and so returns an empty sequence. If this is the case the sequence of the BioBrick must be fed manually to the AutoAnnotator by pasting the DNA sequence into its input window. In the resulting output two positions in the code will be clearly marked by

<!------------------------Enter BioBrick number here------------------------>

where the user should enter the BioBrick number (e.g. K801060 or E0040) in the copied table to activate the link to the part description.

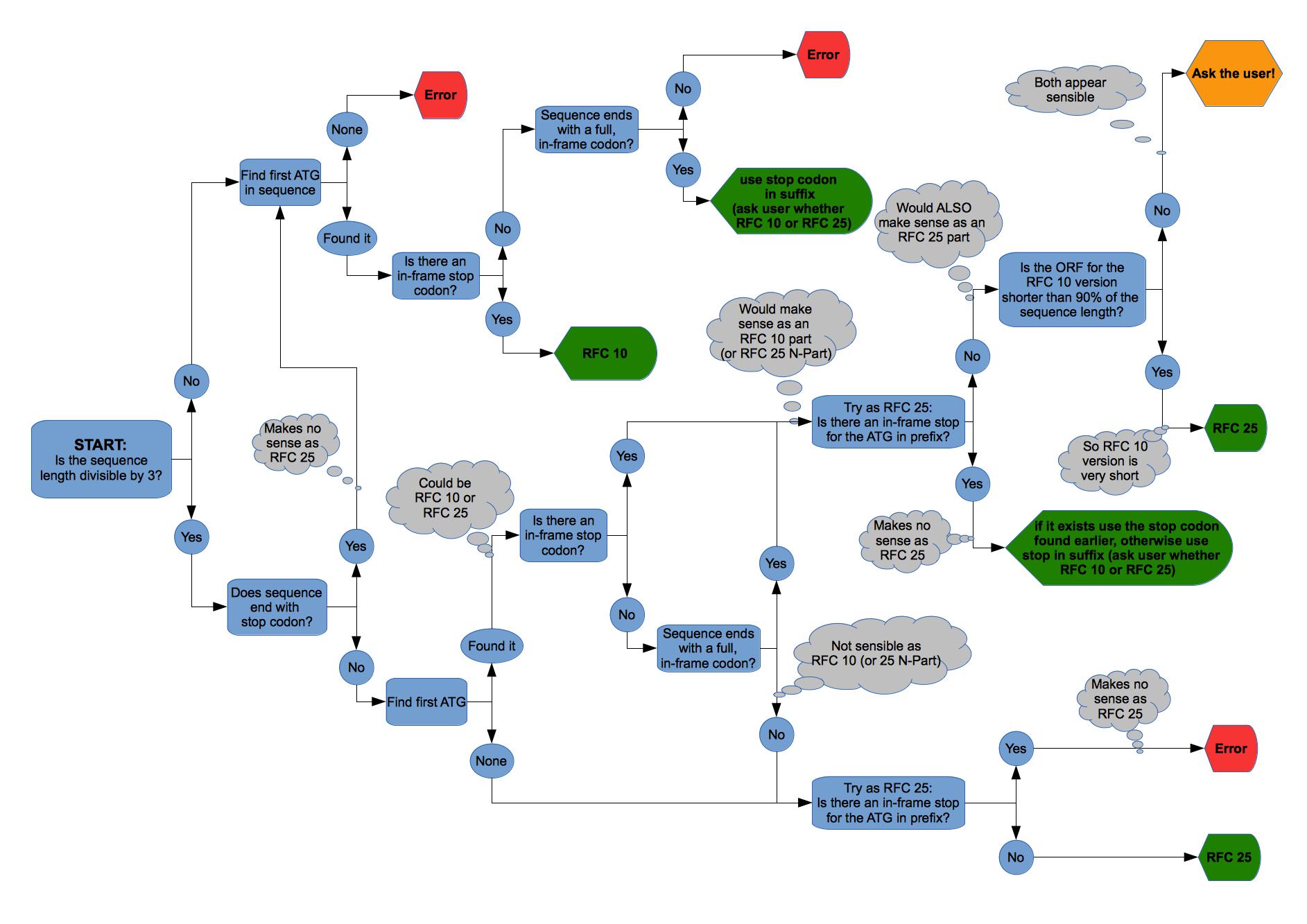

Determination of the Open Reading Frame

The first step is to work out the Assembly Standard of the BioBrick, since parts of the coding sequence may be in the pre- or suffix. As of version 1.0 the most common standards [http://parts.igem.org/Assembly_standard_10 RFC 10] and [http://parts.igem.org/Assembly_standard_25 RFC 25] are supported. Then the first start codon ATG is used and the first corresponding in-frame stop codon determined. These are taken to be the open reading frame.

The complete algorithm to find the Assembly Standard and the Open Reading Frame is illustrated in figure 2 on the right. After finding the Open Reading Frame (ORF) its length is compared to the length of the DNA sequence. If the ORF is less than three quarters (75%) of the DNA sequence, the user is warned that something may be wrong, because usually BioBricks should not have so many non-encoding nucleotides in them.

Should for some reason the automatically determined ORF be incorrect (which should always be checked by the user), the complete protein encoding sequence - starting with the ATG start codon and ending with a stop codon - should be entered manually. In this case the AutoAnnotator will always pick the correct frame.

Recognizing Sequence Features

There are several useful building blocks, which are frequently integrated into BioBricks, such as different tags for analytical purposes or cleavage and docking sites for protein interaction. We have put together a list of such common sequence features and the AutoAnnotator automatically looks for these, lists the appearing features and highlights them in the amino sequence. For the currently supported features please see the Feature List. If you have any suggestions for other interesting features, please get in touch and we will add them.

Computation of Parameters

Amino acid counting, atomic composition and molecular weight

The amino acid counting section is straight forward from the amino acid sequence. Then with the amino acid composition the atomic composition can easily be calculated by using the atomic composition of each amino acid (e.g. given [http://www.matrixscience.com/help/aa_help.html here]) and adding a water molecule (for the ends). Similarly the molecular weight is obtained by adding the individual weights (using the [http://web.expasy.org/findmod/findmod_masses.html#AA average isotopic masses]) and again adding the molecular weight of a water molecule.

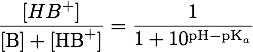

Theoretical pI

The theoretical pI is the isoelectric point of the protein ignoring effects due to folding, which can't be computed properly. By definition the isoelectric point of a protein is the pH-value where the overall charge of the protein is zero, so we need to relate the pH value to the charges of the amino acids. For acid groups HA this is done by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, where pKa is the negative logarithm of the acid dissociation constant:

We can rearrange this to get the fraction of molecules, which are deprotonised and so negatively charged:

Analogously by regarding HB+ as an acid, where B is a base, we can obtain the fraction of positively charged molecules:

These fractions can also be regarded as a "fractional charge", because they give the average charge over all molecules of this type. So by adding up the fractional charge of each amino acid (those with non-basic and non-acidic residues contribute no charge) and those for the N- and C-terminal groups we can determine the charge of the protein at a specific pH. The dissociation constants were taken from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8125050 Bjellqvist et al., 1993 & http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8055880 Bjellqvist et al., 1994, which are also those used by the [http://web.expasy.org/protparam/ ExPASy ProtParam Tool] and are also shown in the tables 1 and 2 below:

| Positively charged groups | |

|---|---|

| Group | pKa |

| Lysine residue | 10.00 |

| Arginine residue | 12.00 |

| Histidine | 5.98 |

| N-terminal -NH2 (unless specified otherwise) | 7.50 |

| N-terminal -NH2 on Alanine | 7.59 |

| N-terminal -NH2 on Methionine | 7.00 |

| N-terminal -NH2 on Serine | 6.93 |

| N-terminal -NH2 on Proline | 8.36 |

| N-terminal -NH2 on Threonine | 6.82 |

| N-terminal -NH2 on Valine | 7.44 |

| N-terminal -NH2 on Glutamic acid | 7.70 |

| Negatively charged groups | |

|---|---|

| Group | pKa |

| C-terminal -COOH | 3.55 |

| Aspartic acid residue | 4.05 |

| Glutamic acid residue | 4.45 |

| Cysteine residue | 9.00 |

| Tyrosine residue | 10.00 |

Now all that remains to be done is to find the pH such that the total charge is zero. This is most easily done by the bisection method: Start with pH=7.0 and determine the charge there. If it is positive, we know the pI must be greater than 7.0 and so we only consider that interval. If it is negative, we continue with the lower half of the pH range. In the subinterval we again evaluate the charge at its middle and choose a subinterval accordingly. By repeating this algorithm we halve the remaining range of pH values on every recursion and can determine the theoretical isoelectric point upto our required precision by continuing until the remaining range is smaller than that precision. However it has to be noted, that the pKa values are only estimations, which depend on the experimental procedure (so you will find many different values in the literature), and that modifications to the protein and the formation of disulfide bridges affect the isoelectric point significantly, so it doesn't make sense to choose a precision of less than 0.01.

Extinction coefficient at 280 nm

The calculation of the extinction coefficient of a protein at 280 nm from its amino acid composition is straight-forward http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2610349 Gill and von Hippel, 1989. The only residues absorbing at this wavelength are those of Tyrosine, Tryptophan and Cystine (which consists of two Cysteines forming a disulfide bridge). Then the extinction coefficient is given by

where Numb(amino acid) is the number of appearances of that amino acid in the protein. Since the number of formed disulfide bridges is impossible to calculate, two values are calculated: One under the assumption that all Cysteines are reduced, i.e. that there are no disulfide bridges, the other assuming that every Cysteine is oxidized and hence part of a disulfide bridge.

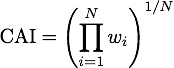

Codon Adaptation Index (CAI)

The Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) measures the "distance" in codon usage between the gene in question and a set of highly expressed reference genes, giving an indicator of the expression rate of the gene in question. The CAI was first introduced by http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC340524/ Sharp and Li, 1987 and is the most widespread measure of codon usage bias.

We chose to include the bacteria E. coli and B. subtilis, the yeast S. cerevisiae, because these are the organisms used most frequently in iGEM. Further we added the codon usage of Mammals (in particular of Mus musculus), of the model plant A. thaliana and of the moss P. patens, which we introduced to iGEM as a chassis this year, because these offer very interesting applications and more options. The codon usages for the reference sets of these organisms were obtained from the [http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/ Codon Usage Database] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10592250 Nakamura et al., 2000.

Average hydrophobicity and charge

For each stretch of five amino acids in the sequence the average hydrophobicity (based on the Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity index http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022283682905150 Kyte and Doolittle, 1982) and the average charge (following [http://emboss.sourceforge.net/apps/release/6.5/emboss/apps/charge.html EMBOSS: charge]) of the residues are calculated and plotted in the graph. These two characteristics of the sequence can be very useful to determine transmembrane regions (~20 hydrophobic residues embedded into the membrane followed by a stop-transfer sequence of a few positively charged acids) and other properties, such as the before mentioned stop-transfer sequences.

Alignments and Predictions

This information is provided to us by the [http://rostlab.org Rost group], who kindly granted us access to the servers and data bases of their prediction site [http://predictprotein.org PredictProtein.org] (see Attributions). The sequence is aligned http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9254694 Altschul et al., 1997 against the [http://web.expasy.org/docs/swiss-prot_guideline.html Swiss-Prot] (manual annotation and review) and [http://web.expasy.org/docs/userman.html#what_is_trembl TrEMBL] (automatic annotation, extensive) protein databases, as well as against the [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/static.do?p=general_information/about_pdb/index.html Protein Data Bank (PDB)] for 3D structures. For each of these the two alignments with the highest identity and those with an identity above 97% are given together with the number of amino acids which were aligned. So for example for a fusion protein it is perfectly possible to get two completely different alignments with 100% identity on different subparts of the amino acid sequence.

The server also produces various predictions. For more information about how these are obtained, please see the corresponding papers by the [http://rostlab.org Rost group]:

- for secondary structure and solvent accessibility: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15215403 Rost et al., 2004

- for transmembrane helices: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8844859 Rost et al., 1996

- for disulfide bridges: http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/34/suppl_2/W177.full Frasconi et al., 2006

- for sub-cellular localization: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22962467 Rost et al., 2012

- for gene ontology: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/14/S3/S7 Rost et al., 2013

These results are stored on the server for more than 30 million amino acid sequences and are instantly available for these. If however a sequence is entered, which has not been calculated yet, the computations are initialized and should be ready in a few hours. In this case the user will be informed and told to return and rerun the AutoAnnotator later.

Export of the Computed Parameters

The results are then combined in a standardized HTML-Table, which is presented to the user. Additionally the HTML code of the table is given, allowing for a quick and easy copy&paste into any wiki page or part description. Here is an example of the produced table with the graphical plot section hidden, but you can open it by pressing the "Show" button in the table. The appearing plot contains the average hydrophobicity and charge, as well as the structural predictions. These can be toggle on and off by using the check-boxes.

| Protein data table for BioBrick BBa_K801060 automatically created by the BioBrick-AutoAnnotator version 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide sequence in RFC 10: (underlined part encodes the protein) GTACACAATGCGTCGT ... TTCGAAAAATAA ORF from nucleotide position 8 to 1705 (excluding stop-codon) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amino acid sequence: (RFC 25 scars in shown in bold, other sequence features underlined; both given below)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sequence features: (with their position in the amino acid sequence, see the list of supported features)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amino acid composition:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amino acid counting

| Biochemical parameters

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plot for hydrophobicity, charge, predicted secondary structure, solvent accessability, transmembrane helices and disulfid bridges | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Codon usage

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alignments (obtained from PredictProtein.org)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predictions (obtained from PredictProtein.org) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subcellular Localization (reliability in brackets)

| Gene Ontology (reliability in brackets)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Predicted features:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The BioBrick-AutoAnnotator was created by TU-Munich 2013 iGEM team. For more information please see the documentation. If you have any questions, comments or suggestions, please leave us a comment. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Programming of the BioBrick-Autoannotator

The Annotator is a JavaScript program using the [http://jquery.com jQuery] library (version 1.10.0) and an [http://james.padolsey.com/javascript/cross-domain-requests-with-jquery/ extension] to the .ajax() method in jQuery written by James Padolsey (also see Import of BioBrick Sequences above). The plot was created using the jQuery library [http://www.flotcharts.org Flot]. This uses the "<canvas>"-tag, which is not supported for Internet Explorer before version 9.0, so for these browsers a work-around using [http://code.google.com/p/explorercanvas/ excanvas.js] is employed. To convert the sequence to its MD5-sum the [http://pajhome.org.uk/crypt/md5/md5.html md5.js] script written by [http://pajhome.org.uk/index.html Paul Johnston] was used. The output is HTML-code including style markup and some JavaScript to enable hiding the plot and the features in it.

The main source code of the BioBrick-Autoannotator version 1.0

For simplicity and speed jQuery.js, AjaxExtension.js, Flot.js, md5.js, events.js and excanvas.js were copied to the iGEM server.

Standardized Annotation of Protein-encoding BioBricks

A central idea of iGEM and BioBricks is standardization. However, the part descriptions in the Registry are not really standardized and every team provides different information in different places (if at all). This makes finding and assessing BioBricks for a new project very time-consuming and frustrating, since one may have to search through the description or turn to external sources. Especially for protein-encoding Bricks there is a lot of information, which can be calculated directly from the DNA sequence. So in the [http://openwetware.org/wiki/The_BioBricks_Foundation:RFC#BBF_RFC_96:_The_AutoAnnotator_-_Standardized_annotation_of_protein-encoding_BioBricks RFC 96] we propose a standard table containing basic parameters, characteristics and predictions for protein-encoding BioBricks. Furthermore we developed a tool, the AutoAnnotator, with which this table can easily be created, so it only needs to be pasted into the part description. For more information on how the AutoAnnotator works, please see our Software page.

You can view the full BBF RFC 96 as a PDF document or in the gallery below.

References:

[PredictProtein] Website

[Prof. Rost] Lab Homepage

http://james.padolsey.com/ James Padolsey Homepage

http://developer.yahoo.com/yql/ web page about YQL

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8125050 Bjellqvist et al., 1993 Bjellqvist, B., Hughes, G.J., Pasquali, Ch., Paquet, N., Ravier, F., Sanchez, J.-Ch., Frutiger, S. and Hochstrasser, D.F. (1993). The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis, 14:1023-1031.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8055880 Bjellqvist et al., 1994 Bjellqvist, B., Basse, B., Olsen, E. and Celis, J.E. (1994). Reference points for comparisons of two-dimensional maps of proteins from different human cell types defined in a pH scale where isoelectric points correlate with polypeptide compositions. Electrophoresis, 15:529-539.

http://web.expasy.org/protparam/ web page about ProtParam tool

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2610349 Gill and von Hippel, 1989 Gill, S.C. and von Hippel, P.H. (1989). Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem., 182:319-326.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC340524/ Sharp and Li, 1987 Sharp, P.M. and Li, W.H. (1987). The Codon Adaptation Index-a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 15(3):1281–95.

http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/ Codon Usage Database

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10592250 Nakamura et al. Nakamura, Y., Gojobori, T. and Ikemura, T. (2000). Codon usage tabulated from the international DNA sequence databases: status for the year 2000. Nucl. Acids Res., 28:292.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022283682905150 Kyte and Doolittle, 1982 Kyte, J. and Doolittle, R.F. (1982). A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of Molecular Biology, 157(1):105-132.

http://emboss.sourceforge.net/apps/release/6.5/emboss/apps/charge.html web page about emboss charge

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9254694 Altschul et al., 1997 Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schäffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., Lipman, D.J. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402.

http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/static.do?p=general_information/about_pdb/index.html PDB Data Bank

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15215403 Rost et al., 2004 Rost, B., Yachdav, G. and Liu, J. (2004). The PredictProtein server. Nucleic Acid Res. 32:321-326.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8844859 Rost et al., 1996 Rost, B., Fariselli, P. and Casadio, R. (1996). Topology prediction for helical transmembrane proteins at 86% accuracy. Protein Sci. 5:1704-1718.

http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/34/suppl_2/W177.full Frasconi et al., 2006 Ceroni, A., Passerini, A., Vullo, A. and Frasconi, P. (2006). DISULFIND: a disulfide bonding state and cysteine connectivity prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:177-181.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22962467 Rost et al., 2012 Goldberg, T., Hamp, T. and Rost, B. (2012). LocTree2 predicts localization for all domains of life. Bioinformatics 28:i458-i465.

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/14/S3/S7 Rost et al., 2013 Hamp, T., Kassner, R., Seemayer, S., Vicedo, E., Schaefer, C., Achten, D., Auer, F., Boehm, A., Braun, T., Hecht, M., Heron, M., Honigschmid, P., Hopf, T.A., Kaufmann, S., Kiening, M., Krompass, D., Landerer, C., Mahlich, Y., Roos, M. and Rost B (2013). Homology-based inference sets the bar high for protein function prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 14(Suppl.3):S7.

http://jquery.com/ web page about jquery

http://www.flotcharts.org/ Flot: JavaScript plotting library for jQuery

http://code.google.com/p/explorercanvas/ web page about explorercanvas

http://pajhome.org.uk/crypt/md5/md5.html Paul Johnston md5.js script

"

"

AutoAnnotator:

Follow us:

Address:

iGEM Team TU-Munich

Emil-Erlenmeyer-Forum 5

85354 Freising, Germany

Email: igem@wzw.tum.de

Phone: +49 8161 71-4351