Team:Duke/Modeling/1

From 2013.igem.org

Hyunsoo kim (Talk | contribs) (→Hill Equation) |

Hyunsoo kim (Talk | contribs) (→Mathematical Modeling of Bistable Toggle Switch) |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

= '''Mathematical Modeling of Bistable Toggle Switch''' = | = '''Mathematical Modeling of Bistable Toggle Switch''' = | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition to our experimental efforts, we have developed mathematical models in two different approaches to aid the construction of a successful toggle switch in <i>S.cerevisiae</i>. Following the construction and characterization of a library of genes parts, one must choose two genes to couple in order to make a working toggle switch. The goal of modeling was to provide theoretical guidance to choosing the optimal pair of genes that will make a toggle switch. With the two models we have developed, we could not only '''demonstrate how various characteristics of the gene affect cooperativity and bistability''', but also understand '''the requirements for building a successful genetic switch'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br><br> | ||

== Cooperativity == | == Cooperativity == | ||

Cooperativity is a common phenomenon in biological systems involving multiple ligands binding to enzymes or receptors. The change in affinity of a binding site for a ligand upon a ligand-binding leads to either positive cooperativity in which affinity is increased and subsequent binding become more likely, or negative cooperativity in which affinity is decreased to hinder future binding. One of the most famous examples of cooperative binding is the binding of oxygen to hemoglobin, the oxygen-transporting protein in red blood cells. When an oxygen molecule bind to hemoglobin, its affinity for oxygen increases greatly, and when three oxygen molecules bind (3-oxy-hemoglobin), its affinity for the fourth one is nearly three-hundred times higher than deoxy-hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen. This cooperative property leads to the sigmoidal shaped curve shown below. | Cooperativity is a common phenomenon in biological systems involving multiple ligands binding to enzymes or receptors. The change in affinity of a binding site for a ligand upon a ligand-binding leads to either positive cooperativity in which affinity is increased and subsequent binding become more likely, or negative cooperativity in which affinity is decreased to hinder future binding. One of the most famous examples of cooperative binding is the binding of oxygen to hemoglobin, the oxygen-transporting protein in red blood cells. When an oxygen molecule bind to hemoglobin, its affinity for oxygen increases greatly, and when three oxygen molecules bind (3-oxy-hemoglobin), its affinity for the fourth one is nearly three-hundred times higher than deoxy-hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen. This cooperative property leads to the sigmoidal shaped curve shown below. | ||

| - | [[File:Cooperativity.png|400px|center]] | + | [[File:Cooperativity.png|400px|center]] |

<div align="center"> Figure 1. Cooperativity of Hemoglobin</div> <br><br> | <div align="center"> Figure 1. Cooperativity of Hemoglobin</div> <br><br> | ||

| - | It has been shown by both mathematical derivation and experimental data that proteins | + | It has been shown by both mathematical derivation and experimental data that proteins which form multimers have cooperativity (Phillips et al, 2012). A transcriptional repressor of the lac operon, lacI proteins form tetramers and show cooperative repression of transcription. Similarly, tetracycline repressor (tetR) found in E.coli form dimers, and as a result show cooperativity. Professors Hermann Bujard and Manfred Gossen at University of Heidelberg developed a synthetic transcription factor called Tet-On and Tet-Off using this naturally found tetR respressor (Gossen, 1992). By fusing VP16 activator found in Herpes Simplex Virus with tetR, they made synthetic repressors (tetracycline transactivator, tTA) that could target specific locations named TetO operator sequences. |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| - | In addition to multimerization, combinatorial promoter binding has been shown to generate cooperativity. Having multiple operator sites for both inducers and repressors produced cooperative response and it is this design that we chose to use in our project (with multiple binding sites for iTALs and CRISPR-Cas9). Cooperativity of repressors with multiple binding sites will be further explored in our mathematical models. | + | In addition to multimerization, combinatorial promoter binding has been shown to generate cooperativity (Murphy et al, 2007). Having multiple operator sites for both inducers and repressors produced cooperative response and it is this design that we chose to use in our project (with multiple binding sites for iTALs and CRISPR-Cas9). Cooperativity of repressors with multiple binding sites will be further explored in our mathematical models. |

<br><br><br> | <br><br><br> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 26: | ||

[[File:Hill_Equation.png|150px|center]] <br> | [[File:Hill_Equation.png|150px|center]] <br> | ||

| - | <div align="center"> Figure 2. Hill Equation </div> | + | <div align="center"> Figure 2. Hill Equation (Induction) </div> |

| - | In the Hill Equation shown above, theta represents the fraction of binding sites occupied by ligands, [L] is the ligand concentration, n is the Hill coefficient, and Kd is the dissociation constant of the ligand. The value of the Hill coefficient describes the cooperativity of ligand binding: n>1 for positive cooperativity, n<1 for negative cooperativity and n=0 for no cooperativity. The above equation can also be applied to cooperative induction or activation of transcription, where theta represents the level of mRNA produced and [L] represents the level of inducer present. More cooperative the activation is, the steeper the slope will be, and the expression of the gene becomes more switch-like with distinct on and off states without intermediate states. Shown below is the graph the of Hill equation with various Hill coefficients. As one can see, increasing the Hill coefficient makes the change (induction) more abrupt and switch-like. | + | In the Hill Equation shown above, theta represents the fraction of binding sites occupied by ligands, [L] is the ligand concentration, n is the Hill coefficient, and Kd is the dissociation constant of the ligand. The value of the Hill coefficient describes the cooperativity of ligand binding: n>1 for positive cooperativity, n<1 for negative cooperativity and n=0 for no cooperativity. The above equation can also be applied to cooperative induction or activation of transcription, where theta represents the level of mRNA produced and [L] represents the level of inducer present. More cooperative the activation is, the steeper the slope will be, and the expression of the gene becomes more switch-like with distinct on-and-off states without intermediate states. Shown below is the graph the of Hill equation with various Hill coefficients. As one can see, increasing the Hill coefficient makes the change (induction) more abrupt and switch-like. |

[[File:Hill_Graph.png|400px|center]] <br> | [[File:Hill_Graph.png|400px|center]] <br> | ||

| - | <div align="center"> Figure | + | <div align="center"> Figure 3. Graph of Hill Equation (Induction) </div> <br> |

| + | |||

| + | Similarly, mathematical derivation of a system with repressors that cooperatively repress a gene expression can be modeled by the following equation shown below. Again, Theta represents the level of transcribed mRNA, and [L] represents the level of repressors present. The graph of the above equation is shown as well. Similar to the previous graph, the level of transcription switches more abruptly with higher cooperativity (higher Hill coefficient). Therefore, as shown in both cases, high cooperativity lead to switch-like behavior and is favorable when designing a bistable toggle switch. | ||

| - | [[File:Hill_Equation1.png|150px|center]] <br> | + | [[File:Hill_Equation1.png|150px|center]]<br> |

| - | <div align="center"> Figure | + | <div align="center"> Figure 4. Hill Equation (Repression) </div> <br><br> |

| + | [[File:Hill_Graph2.png|400px|center]] | ||

| + | <div align="center"> Figure 5. Graph of the Hill Equation (Repression) </div> | ||

| Line 38: | Line 46: | ||

<br><br><br> | <br><br><br> | ||

| - | =References= | + | ==References== |

| + | #Phillips R, Kondev J, Theriot J, Garcia H: Physical Biology of the Cell. Taylor & Francis; 2012. | ||

| + | #Gossen M, Bujard H: Tight Control of Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells by Tetracycline-Responsive Promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89(12):5547–51. | ||

| + | #Murphy K.F., Balazsi G., Collins J.J.: Combinatorial promoter design for engineering noisy gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007, 104:pp. 12726–12731 | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| + | <!--#Bintu L, Buchler NE, Garcia HG, Gerland U, Hwa T, Kondev J,Kuhlman T, Phillips R: Transcriptional regulation by the numbers: models. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2005, 15:125-135.--> | ||

| + | <!--#Allen et al., "Directed Mutagenesis in Embryonic Stem Cells". Mouse Genetics and Transgenics: 259–263. (2000)--> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 04:41, 24 September 2013

Contents |

Mathematical Modeling of Bistable Toggle Switch

In addition to our experimental efforts, we have developed mathematical models in two different approaches to aid the construction of a successful toggle switch in S.cerevisiae. Following the construction and characterization of a library of genes parts, one must choose two genes to couple in order to make a working toggle switch. The goal of modeling was to provide theoretical guidance to choosing the optimal pair of genes that will make a toggle switch. With the two models we have developed, we could not only demonstrate how various characteristics of the gene affect cooperativity and bistability, but also understand the requirements for building a successful genetic switch.

Cooperativity

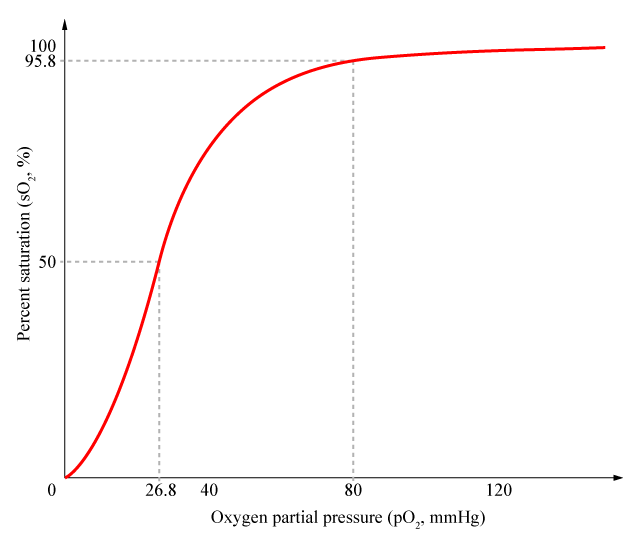

Cooperativity is a common phenomenon in biological systems involving multiple ligands binding to enzymes or receptors. The change in affinity of a binding site for a ligand upon a ligand-binding leads to either positive cooperativity in which affinity is increased and subsequent binding become more likely, or negative cooperativity in which affinity is decreased to hinder future binding. One of the most famous examples of cooperative binding is the binding of oxygen to hemoglobin, the oxygen-transporting protein in red blood cells. When an oxygen molecule bind to hemoglobin, its affinity for oxygen increases greatly, and when three oxygen molecules bind (3-oxy-hemoglobin), its affinity for the fourth one is nearly three-hundred times higher than deoxy-hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen. This cooperative property leads to the sigmoidal shaped curve shown below.

It has been shown by both mathematical derivation and experimental data that proteins which form multimers have cooperativity (Phillips et al, 2012). A transcriptional repressor of the lac operon, lacI proteins form tetramers and show cooperative repression of transcription. Similarly, tetracycline repressor (tetR) found in E.coli form dimers, and as a result show cooperativity. Professors Hermann Bujard and Manfred Gossen at University of Heidelberg developed a synthetic transcription factor called Tet-On and Tet-Off using this naturally found tetR respressor (Gossen, 1992). By fusing VP16 activator found in Herpes Simplex Virus with tetR, they made synthetic repressors (tetracycline transactivator, tTA) that could target specific locations named TetO operator sequences.

In addition to multimerization, combinatorial promoter binding has been shown to generate cooperativity (Murphy et al, 2007). Having multiple operator sites for both inducers and repressors produced cooperative response and it is this design that we chose to use in our project (with multiple binding sites for iTALs and CRISPR-Cas9). Cooperativity of repressors with multiple binding sites will be further explored in our mathematical models.

Hill Equation

Named after English physiologist Archibald Vivian Hill who studied the sigmoidal binding curve of hemoglobin, the Hill Equation provides a way to quantify cooperativity. The equation describes the fraction of proteins or enzymes that are saturated by ligands as a function of the concentration of ligands.

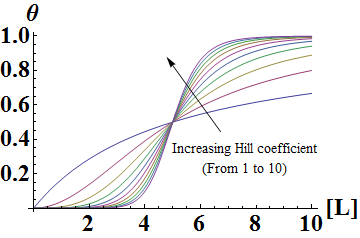

In the Hill Equation shown above, theta represents the fraction of binding sites occupied by ligands, [L] is the ligand concentration, n is the Hill coefficient, and Kd is the dissociation constant of the ligand. The value of the Hill coefficient describes the cooperativity of ligand binding: n>1 for positive cooperativity, n<1 for negative cooperativity and n=0 for no cooperativity. The above equation can also be applied to cooperative induction or activation of transcription, where theta represents the level of mRNA produced and [L] represents the level of inducer present. More cooperative the activation is, the steeper the slope will be, and the expression of the gene becomes more switch-like with distinct on-and-off states without intermediate states. Shown below is the graph the of Hill equation with various Hill coefficients. As one can see, increasing the Hill coefficient makes the change (induction) more abrupt and switch-like.

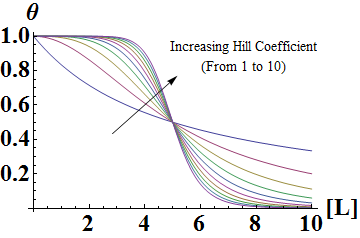

Similarly, mathematical derivation of a system with repressors that cooperatively repress a gene expression can be modeled by the following equation shown below. Again, Theta represents the level of transcribed mRNA, and [L] represents the level of repressors present. The graph of the above equation is shown as well. Similar to the previous graph, the level of transcription switches more abruptly with higher cooperativity (higher Hill coefficient). Therefore, as shown in both cases, high cooperativity lead to switch-like behavior and is favorable when designing a bistable toggle switch.

References

- Phillips R, Kondev J, Theriot J, Garcia H: Physical Biology of the Cell. Taylor & Francis; 2012.

- Gossen M, Bujard H: Tight Control of Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells by Tetracycline-Responsive Promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89(12):5547–51.

- Murphy K.F., Balazsi G., Collins J.J.: Combinatorial promoter design for engineering noisy gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007, 104:pp. 12726–12731

"

"