Team:Duke/Modeling/Cooperativity

From 2013.igem.org

Contents |

Mathematical Modeling of Bistable Toggle Switch

Our Goal

In addition to our experimental efforts, we have developed mathematical models in two different approaches to aid the construction of a successful toggle switch in S.cerevisiae. Following the construction and characterization of a library of genes parts, one must choose two genes to couple in order to make a working toggle switch. The goal of modeling was to provide theoretical guidance to choosing the optimal pair of genes that will make a toggle switch. With the two models we have developed, we could not only demonstrate how various characteristics of the gene affect cooperativity and bistability, but also understand the requirements for building a successful genetic switch.

Before introducing our mathematical models for genetic toggle switch, two important concepts must be explained: cooperativity and the Hill equation. These two ideas are widely used to characterize and model various biological systems. Specifically in our models, cooperativity was one of the key parameters for the characterizing repressor activity, while Hill equation was a standard model to which results from our models were compared.

Background Knowledge

Cooperativity

Cooperativity is a common phenomenon in biological systems involving multiple ligands binding to enzymes or receptors. The change in affinity of a binding site for a ligand upon a ligand-binding leads to either positive cooperativity in which affinity is increased and subsequent binding become more likely, or negative cooperativity in which affinity is decreased to hinder future binding. Cooperativity is critical for ideal gene circuits’ function because high cooperativity can lead to sudden change in states (i.e. fast switch between “off” state and “on” state). One of the most famous examples of cooperativity in biological systems is the binding of oxygen to hemoglobin, where its affinity for oxygen increases after each additional oxygen-binding. As a result, cooperativity results in non-linear and sigmoidal shaped curves.

It has been shown by both mathematical derivation and experimental data that proteins which form multimers have cooperativity (Phillips et al, 2012). For example, a transcriptional repressor of the lac operon, lacI proteins form tetramers and show cooperative repression of transcription. Similarly, tetracycline repressor (tetR) found in E.coli form dimers, and as a result show cooperativity. The nonlinearity of cooperativity can be explained by using rate equations for multimerization.

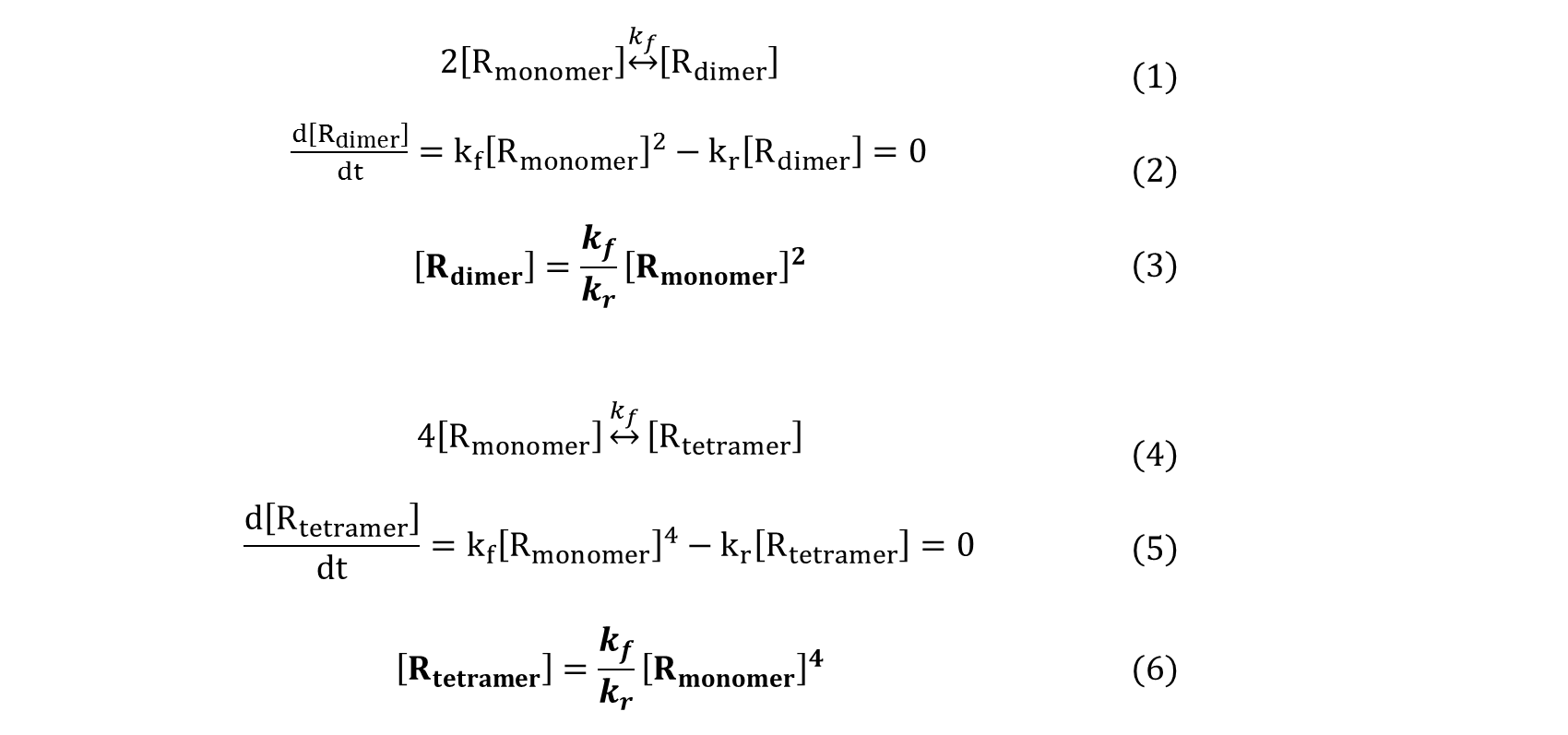

For a repressor that must multimerize to become active, the concentration of the multimer species effectively drives the reaction. As equation (3) shows, the concentration of dimer is proportional to the square of the concentration of monomer when in equilibrium. Similarly, equation (6) shows that the concentration of tetramer is proportional to the 4th power of the concentration of monomer. As a result, a linear increase in monomer concentration leads to nonlinear increase of the concentration of active multimerized-repressors, and thus shows cooperativity.

In addition to multimerization, combinatorial promoter binding has been shown to generate cooperativity (Murphy et al, 2007).

Assuming that all binding site with one or more repressors bound can repress RNA polymerase from binding, results similar to that of multimerization can be derived. Shown above is an example derviation for a promoter with three repressor binding sites. As shown in the equations, the level of effective species (promoter with one, two or three repressors bound) depend on the cube of level of repressors.

Murphy et al has shown that having multiple operator sites for both inducers and repressors produced cooperative response and it is this design that we chose to use in our project (with multiple binding sites for TALEs and sgRNA-dCas9). Cooperativity of repressors with multiple binding sites will be further explored in our mathematical models.

Hill Equation

The Hill Equation is another important concept that we have used extensively in our models. As will be explain below, this equation often used by many researchers to model gene circuits because of its is a simplicity and ability to capture important aspects of how a gene circuit behaves (Ajo-Franklin 2007, Murphy 2007, Wall 2004).

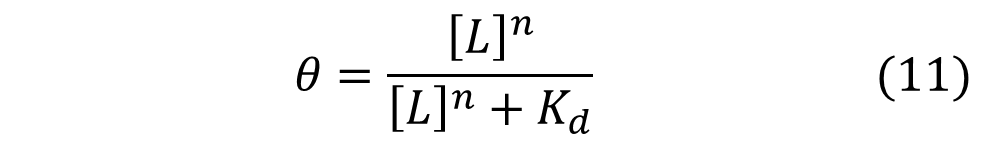

Named after English physiologist Archibald Vivian Hill who studied the sigmoidal binding curve of hemoglobin, the Hill Equation provides a way to quantify cooperativity. The equation describes the fraction of proteins or enzymes that are saturated by ligands as a function of the concentration of ligands.

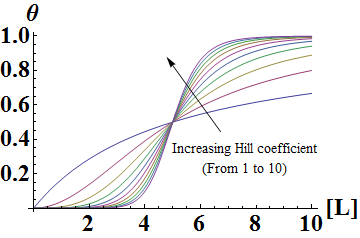

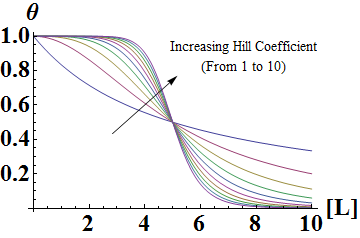

In the Hill Equation shown above, θ represents the fraction of binding sites occupied by ligands, [L] is the ligand concentration, n is the Hill coefficient, and Kd is the dissociation constant of the ligand. The value of the Hill coefficient describes the cooperativity of ligand binding: n>1 for positive cooperativity, n<1 for negative cooperativity and n=0 for no cooperativity. The above equation can also be applied to cooperative induction or activation of transcription, where θ represents the level of mRNA produced and [L] represents the level of inducer present. More cooperative the activation is, the steeper the slope will be, and the expression of the gene becomes more switch-like with distinct on-and-off states without intermediate states. Shown below is the graph the of Hill equation with various Hill coefficients. As one can see, increasing the Hill coefficient makes the change (induction) more abrupt and switch-like.

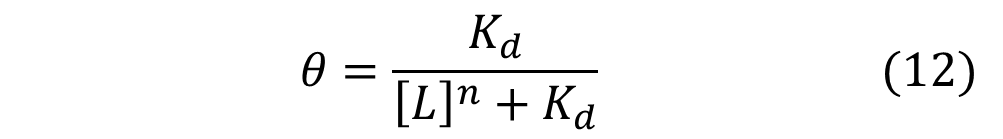

Similarly, mathematical derivation of a system with repressors that cooperatively repress a gene expression can be modeled by the following equation shown below. Again, θ represents the level of transcribed mRNA, and [L] represents the level of repressors present. The graph of the above equation is shown as well. Similar to the previous graph, the level of transcription switches more abruptly with higher cooperativity (higher Hill coefficient). Therefore, as shown in both cases, high cooperativity lead to switch-like behavior and is favorable when designing a bistable toggle switch.

References

- Phillips R, Kondev J, Theriot J, Garcia H: Physical Biology of the Cell. Taylor & Francis; 2012.

- Murphy K.F., Balazsi G., Collins J.J.: Combinatorial promoter design for engineering noisy gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007, 104:12726–12731.

- Ajo-Franklin C.M., Drubin D.A., Eskin J.A., Gee E.P.S.,Landgraf D., Phillips I., Silver P.A.: Rational design of memory in eukaryotic cells. Genes & development 2007, 21:2271-2276.

- Wall M.E., Hlavacek W.S., Savageau M.A: Design of gene circuits: lessons from bacteria. Nature Review Genetics 2004, 5:32-42.

Modeling Pages

- Cooperativity and Hill Equation (You are here)

- Thermodynamic Model: Introduction

- Thermodynamic Model: Application

- Kinetic Model

Supplementary Materials

"

"