Team:Leeds/Results

From 2013.igem.org

| (40 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

$('div#touchgallery1').touchgallery({ // initialize first demo | $('div#touchgallery1').touchgallery({ // initialize first demo | ||

width: 750, | width: 750, | ||

| - | height: | + | height: 427 |

}) | }) | ||

$('div#touchgallery2').touchgallery({ // initialize second demo | $('div#touchgallery2').touchgallery({ // initialize second demo | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

</head> | </head> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | {{Team:Leeds_layout|Header=Experimental Results|content= | + | {{Team:Leeds_layout|HeaderParky=</div>[[File:Leeds_BlackboardParky.png|150px|link=|frameless]]<div>|HeaderImage=[[File:Leeds_LabHeader.png|825px|link=|frameless]]|Header=Experimental Results|content= |

| - | + | Data shown here provide evidence that our MicroBeagle strategy is feasibly, but that optimization is required in order to achieve improved expression of cell surface displayed target-binding proteins, and to modify the level of the stress-responsive promoter activation to make it operable over larger growth regimes. The current version (v1) of MicroBeagle is only effective at late growth stages. | |

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

==Bacterial growth curves== | ==Bacterial growth curves== | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

===Control Bacterial Growth Curve=== | ===Control Bacterial Growth Curve=== | ||

[[File:Leeds_Controlgrowthcurve.png|right|500px|Control growth-curve for Competent Cells, click for full image|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/16/Leeds_Controlgrowthcurve.png|frameless]] | [[File:Leeds_Controlgrowthcurve.png|right|500px|Control growth-curve for Competent Cells, click for full image|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/16/Leeds_Controlgrowthcurve.png|frameless]] | ||

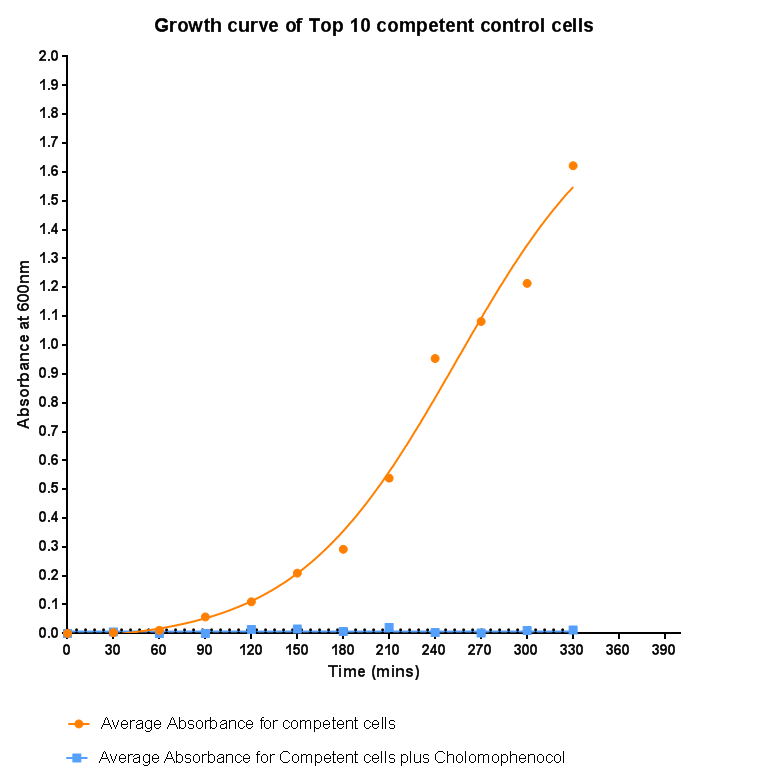

| - | <p align="justify"> | + | <p align="justify">To kickstart lab work for Leeds's first-ever iGEM team, we performed this straightforward experiment in which cells were grown in SB media both in the presence and absence of chloramphenicol. Absorbance measurements taken over time show the growth of the bacteria. Clear lag and log phases are observed when the bacteria are grown in SB media only. But as expected, the graph shows that the bacteria do not grow in the presence of chloramphenicol. This graph was use as a control to compare with device-containing bacteria in order to determine whether the genes we inserted caused an effect on cell growth.</p> |

<br style="clear:both" /> | <br style="clear:both" /> | ||

==Characterisation of Device 1== | ==Characterisation of Device 1== | ||

===Growth Curve=== | ===Growth Curve=== | ||

| - | [[File:Leeds_BS1growthcurve.png|left|500px|Growth curve for Device 1, click to enlarge|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/5b/Leeds_BS1growthcurve.png|frameless]]<p align="justify">Bacteria were grown which contained Device 1; their absorbance was monitored over time and then the rate of growth compared to bacteria that do not contain Device 1. The graph clearly shows that inserting Device 1 into cells considerably slows their growth in log phase compared with the growth of cells without Device 1 | + | [[File:Leeds_BS1growthcurve.png|left|500px|Growth curve for Device 1, click to enlarge|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/5b/Leeds_BS1growthcurve.png|frameless]]<p align="justify">Bacteria were grown which contained Device 1; their absorbance was monitored over time and then the rate of growth compared to bacteria that do not contain Device 1. The graph clearly shows that inserting Device 1 into cells considerably slows their growth in log phase compared with the growth of cells without Device 1, that the lag phase is shorter, and that the cells don't grow to as high an optical density in log phase as the bacteria without Device 1.</p> |

<br style="clear:both" /> | <br style="clear:both" /> | ||

===Membrane Stress=== | ===Membrane Stress=== | ||

| - | [[File:Leeds membranestressgraph2-actualgraphthatweshoulduse.png|left|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/bd/Leeds_membranestressgraph2-actualgraphthatweshoulduse.png|500px| | + | [[File:Leeds membranestressgraph2-actualgraphthatweshoulduse.png|left|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/bd/Leeds_membranestressgraph2-actualgraphthatweshoulduse.png|500px|Click to view full image|frameless]]<p align="justify">Investigation of literature regarding the action and regulation of the Cpx pathway lead to the discovery that the system as a whole responds to a large variety of membrane stresses, something that could be true of the specific promoter we chose to use (pCpxR). We therefore sought to investigate the response of our promoter to each individual membrane stress.</p> |

| - | <p align="justify">Individually many of the experiments produced erratic and seemingly random data which is listed independently below. However plotting all average readings together shows that there is a dramatic increase in response to the stress induced by the silica beads | + | <p align="justify">Individually many of the experiments produced erratic and seemingly random data which is listed independently below. However plotting all average readings together shows that there is a dramatic increase in response to the stress induced by the silica beads relative to all chemically induced membrane stresses tested.</p> |

| - | <p align="justify">This indicates that it would be possible to detect the presence of silica beads in solution, in principle, using our binding and detection system | + | <p align="justify">This indicates that it would be possible to detect the presence of silica beads in solution, in principle, using our binding and detection system. This was certainly successful when silica beads were present at relatively high concentrations. However further work needs to be done to assess whether this high response remains across a range of silica bead concentrations in solution.</p> |

| - | <p align="justify">In light of these results, | + | <p align="justify">In light of these results, additional experiments were conducted to gain further information in which cells were exposed to the stresses of ethanol, Triton X-100 and pH gradients. In this second experiment, a robotic pipette was used to directly fill the 96 well plate to reduce human error, the raw data of which can be found [[Media:Leeds_RoboPipetteSheet.xls|here]]. Excluding wells with imposed pH gradient, all wells were kept at pH 7 using Tris.HCl buffer, the pH gradient was also achieved with a Tris.HCl buffer.</p> |

| - | + | <p align="justify">The 96 well plates (200 microliters/well), prepared with the chemical stressors, were inoculated with 20 microliters of overnight cell culture expressing Device 1 and incubated with shaking for 2 hours at 37 degrees. </p> | |

| - | + | <p align="justify">We also performed preliminary investigation on the effects of temperature extremes on the CpxR promoter but the results were inconclusive and thus warrant further studies, possibly by future Leeds iGEM teams. Listed below is the data for detergent and pH extremes. We note that the response of the Cpx pathway to temperature has been characterized previously in the literature and by [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Parts/Characterization Calgary 2010].</p> | |

| - | In | + | <br style="clear:both" /> |

| - | Excluding wells with imposed pH gradient, all wells were kept at pH 7 using Tris.HCl buffer, the pH gradient was also achieved with a Tris.HCl buffer.</p> | + | |

| - | <p align="justify">The 96 well plates were | + | |

| - | <br style="clear:both"> | + | |

====Triton X-100==== | ====Triton X-100==== | ||

| - | [[File:Triton bs1 graph-no line of best fit.png|right|400px|text-top| | + | [[File:Triton bs1 graph-no line of best fit.png|right|400px|text-top|Click to view full image|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/d1/Leeds_tritonbs1graph1.png|frameless]]<p align="justify">Between the concentration values of 0.1-9.0% triton X-100, the data shows roughly the relationship that was expected, a rise in GFP production as the triton concentration increases. This is likely due to triton acting as a detergent resulting in damage to the plasma membrane of cells, activating the Cpx pathway in general, including the CpxR promoter ([[Team:Leeds/Modeling|pCpxR]]). Past 10% Triton X-100 concentration, it is assumed that cells are dying in large quantities, being unable to produce GFP at all or in very limited amounts before they are killed. This explains the corrected fluorescence readings reducing to below zero.</p> |

| - | The reason for the large spike in fluorescence at Triton concentrations >20% is unclear, a | + | <p align="justify">The reason for the large spike in fluorescence at Triton concentrations >20% is unclear, a possible explanation for this is the total lysis of the cell, expelling all cellular components resulting in background GFP levels having a larger fluorescence reading due to reduced scattering from within the cell.</p> |

| - | + | <p align="justify">It is most important to note that this is preliminary data, from fluorescence based measurments, hence it is expected that with sufficiently high repeat readings, the trends proposed will clarify further. This would again be suggested extension work for future teams.</p> | |

| - | + | <br style="clear:both" /> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | <br style="both | + | |

| - | + | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | ===Membrane Stress - Atomic Force Microscopy=== | + | ===Membrane Stress - (Fluorescence) Atomic Force Microscopy=== |

| - | [[File:Leeds_FluoroAFMImage.jpg|left|500px|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/be/Leeds_FluoroAFMImage.jpg|Fluorescence-AFM image of Bio-device 1. Black triangular shadow holds the AFM cantilever tip, glowing spots are fluorescent bacteria, click to enlarge|frameless]]<p align="justify">Atomic Force Microscopy utilises Van-Der-Waals forces to attract the tip towards a surface, causing the bending of a cantilever, onto which a laser is pointed. The tip deflection causes the laser light to also be deflected and this is tracked using a bank of photodiodes. AFM is typically used to image surfaces at the atomic scale, as well as for Force Spectroscopy. When used in Force Spectroscopy, the tip is brought into direct contact with the sample, allowing the sample protein to bind to the silicon tip. Then, the AFM is slowly retracted at varying | + | [[File:Leeds_FluoroAFMImage.jpg|left|500px|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/be/Leeds_FluoroAFMImage.jpg|text-top|Fluorescence-AFM image of Bio-device 1. Black triangular shadow holds the AFM cantilever tip, glowing spots are fluorescent bacteria, click to enlarge|frameless]]<p align="justify">Atomic Force Microscopy utilises Van-Der-Waals forces to attract the tip towards a surface, causing the bending of a cantilever, onto which a laser is pointed. The tip deflection causes the laser light to also be deflected and this is tracked using a bank of photodiodes. AFM is typically used to image surfaces at the atomic scale, as well as for Force Spectroscopy. When used in Force Spectroscopy, the tip is brought into direct contact with the sample, allowing the sample protein to bind to the silicon tip. Then, the AFM is slowly retracted at varying speeds or to varying distances, applying a force to the protein. This causes portions of the protein to unravel, and the distinct patterns associated with α-helices and β-pleated sheets can be seen in this data. This allows the exact secondary and tertiary structure of a protein to be determined, but also the energy profile of various conformations, which in turn tells us how the protetin folds.</p> |

| - | <p align="justify">For Bio-Device 1 however, the team wanted to measure how much force was required to trigger the stress activated [[Team:Leeds/Modeling|Cpx Pathway]]. This was to be done by observing the culture under the fluoroscope portion of the F-AFM, and then "prod" a bacterium at a low force, slowly increasing the stress until a fluorescence response was seen. This would then give a direct measure of the stress threshold for Cpx, a value currently unknown in the literature. | + | <p align="justify">For Bio-Device 1 however, the team wanted to measure how much force was required to trigger the stress activated [[Team:Leeds/Modeling|Cpx Pathway]]. This was to be done by observing the culture under the fluoroscope portion of the F-AFM, and then "prod" a bacterium at a low force, slowly increasing the stress until a fluorescence response was seen. This would then give a direct measure of the stress threshold for Cpx, a value currently unknown in the literature. This is however, distinctly more difficult that it sounds. Firstly, it can be seen from the image that the culture were already fluorescing a little, likely due to smaller stresses in solution, although some can clearly be seen in the middle of binomial fission, which is known to also activate the pathway. The other issue was with trying to keep the bacterial cells stable enough to continually poke them with AFM tip. Normally, this sort of experiment is typically performed at the Univ of Leeds AFM facility on Giant Unilamellar Vesicles and microbubbles about 5 microns wide. These microstructures are naturally forming precursors to cells, and thus of great interest to [[Team:Leeds/Team#Steve Evans|bio-physicists]]. However, as trying to poke a structure 5 microns wide with a tip only 40nm at its widest is akin to throwing a needle from space onto a ship in the Atlantic ocean, experimenters usually adhere the bubbles to the surface with a binding peptide. This could not be done for [[Team:Leeds/Project#Device 1|Bio-Device 1]] without potentially triggering the pathway, so instead, it was hoped a more viscous solution and some micro-troughs scratched into the glass slide surface would be enough to keep them steady. Again though, bacteria are very different to inert bubbles of lipids, and tend to forcibly move themsleves regardless, hence results remained inconclusive. The approach showed some promise however, and it is hoped further work will be undertaken on this at a later date.</p> |

| + | <p align="justify">The presence of background fluorescence in this experiment agrees with fluorescence confocal data and previous literature suggesting that the pCpxR promoter is active during early and mid-log phase of cell growth (cell division). Again, we are interesting in the possibility of using evolutionary development techniques to mutate a variant promoter, specific for MicroBeagle activity, with a higher threshold stress tolerance than the native Cpx promoter. Other extensions to this work would be in use of characterising the binding domain strengths of [[Team:Leeds/Project#Device 2|MicroBeagle]], and we hope other teams may seek to use similar methods in future.</p> | ||

<br style="clear:both" /> | <br style="clear:both" /> | ||

| - | ==Characterisation of Si4== | + | ==Characterisation of Si4 silica-binding oligo-peptide== |

===Growth Curve=== | ===Growth Curve=== | ||

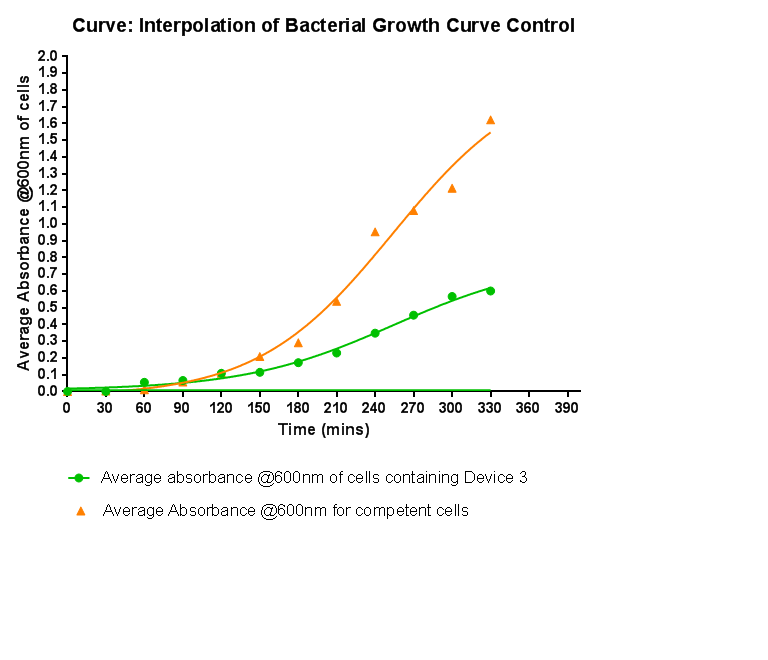

| - | [[File:Leeds_BS2Growthcurve.png|right|500px|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/c/cc/Leeds_BS2Growthcurve.png|Growth curve for Si4, click to enlarge|frameless]]<p align="justify">Here the growth of cells | + | [[File:Leeds_BS2Growthcurve.png|right|500px|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/c/cc/Leeds_BS2Growthcurve.png|Growth curve for Si4, click to enlarge|frameless]]<p align="justify">Here the growth of cells expressing INP-displayed Si4 was monitored via absorbance and compared to the growth of cells that do not contain Si4. As was seen when device 1 was inserted into the cells, the growth is slowed down considerably. Although the graph shows a log and a lag phase for the cells expressing INP-Si4, the absorbance reached in log phase is very low compared to cells without Si4; it is even lower than the absorbance reached for cells containing Device 1.</p> |

<br style="clear:both" /> | <br style="clear:both" /> | ||

| - | ==Characterisation of Device | + | ==Characterisation of Device 2== |

===Growth Curve=== | ===Growth Curve=== | ||

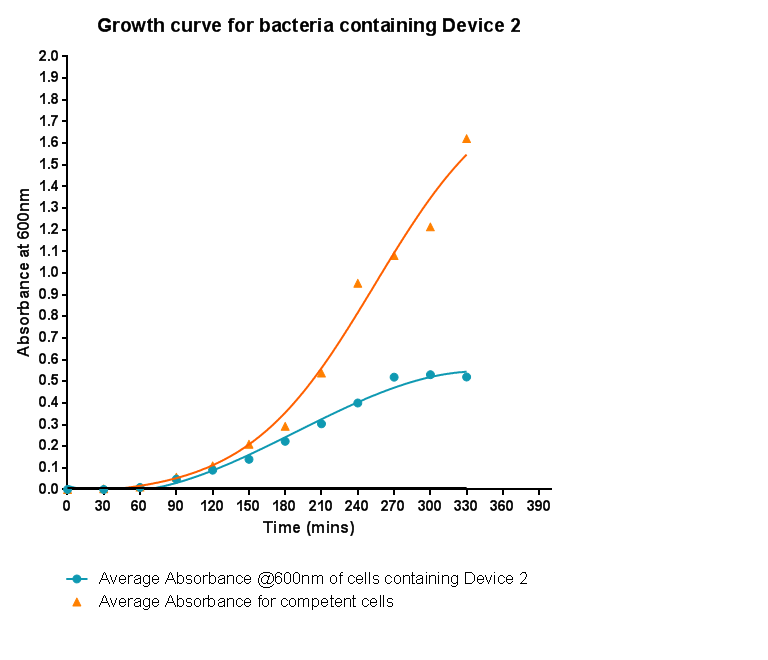

| - | [[File:Leeds_BS3Growthcurve.png|right|500px|Growth curve for Device | + | [[File:Leeds_BS3Growthcurve.png|right|500px|Growth curve for Device 2, click to enlarge|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/c/ca/Leeds_BS3Growthcurve.png|frameless]]<p align="justify">This graph shows the results of monitoring the growth of cells with expressing Device 2. As with other hetereologous expression experiments, growth of the cells is considerably slowed when compared with cells that do not contain any device at all. A slight change in the gradient of the graph can be seen showing the transition of the cell growth from lag to log phase, so the cells are still growing normally, but the insertion of Device 2 is restricting rate of cell growth and final density acheived. We propose that this is due to the increased energy and nutrient requirements to produce the inserted structures.</p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | </p> | + | |

<br style="clear:both" /> | <br style="clear:both" /> | ||

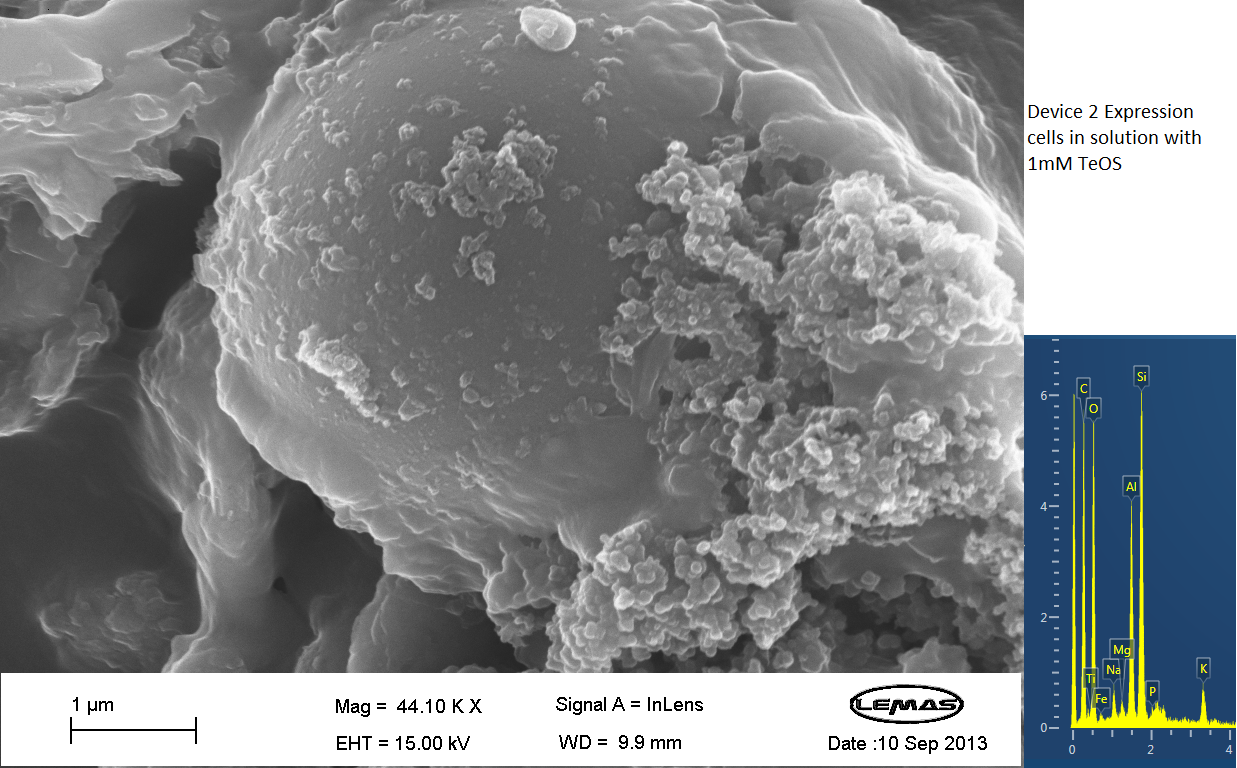

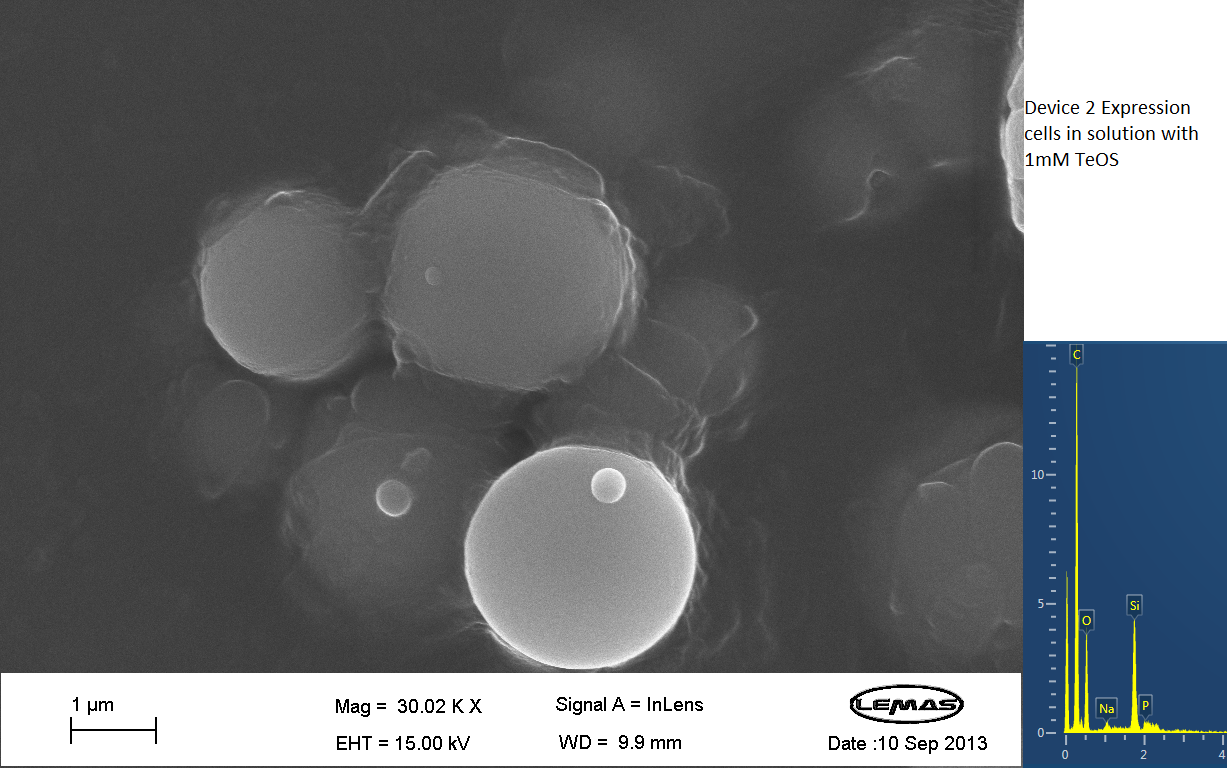

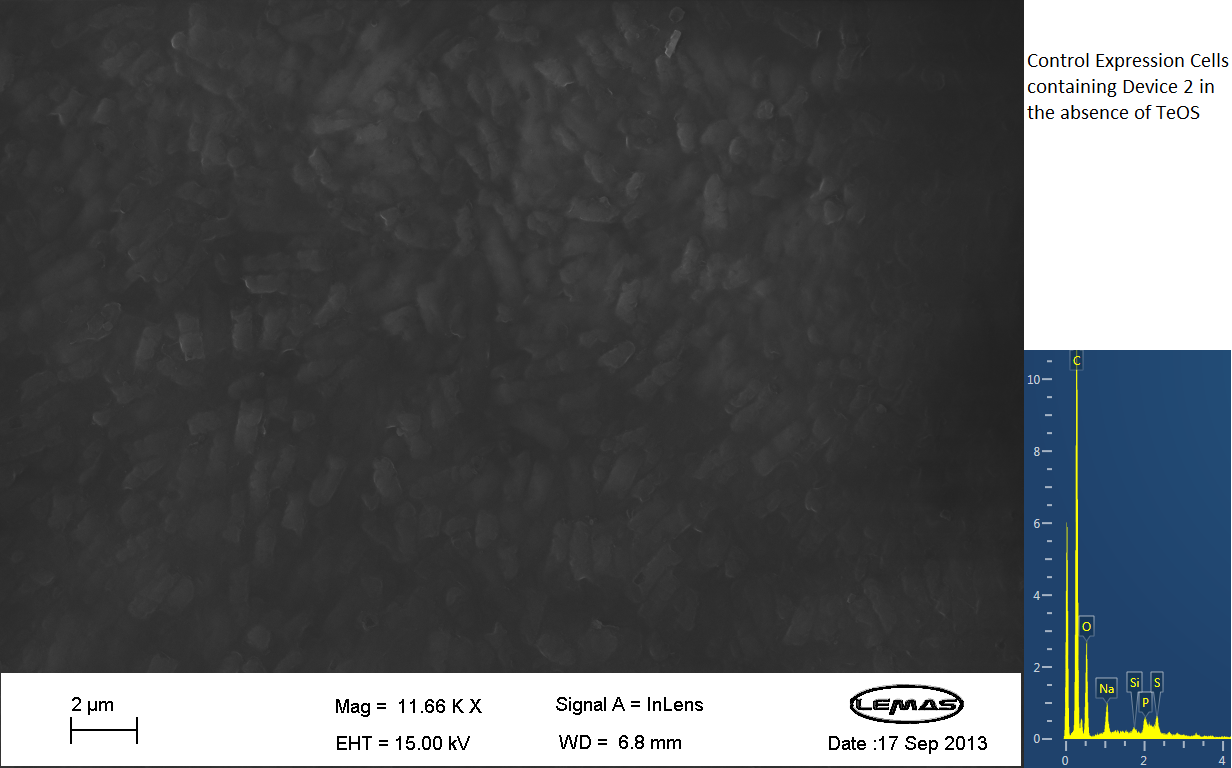

===Scannning Electron Microscopy=== | ===Scannning Electron Microscopy=== | ||

| Line 110: | Line 89: | ||

</div></div> | </div></div> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <p align="justify">The gallery above contains | + | <p align="justify">The gallery above contains Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) data on cells either expressing Device 2 (i.e. displaying Si4), or not (control). Cells were grown overnight and then incubated with 1 mM silicic acid (formed by acid hydrolyzing 1 mM tetraethoxysilane), pelleted by centrifugation and then imaged by SEM, which chemical analysis by electron x-ray dispersive spectroscopy (EDX). Only in the cell samples containing Device 2 were silica-coated cells observed, whereas in the control cell population no cells coated with large quantities of silica were observed. Silica formation is expected to occur through reaction of surface-displayed Si4 with silicic acid in solution. The silica-coated cells shown here were relatively few in the overall population of experimental (Device 2-containing) cells, with large number of experimental cells uncoated. However, no cells in the control were found to be similarly coated by silica. Collectively, these data suggest that Si4 is effectively surface-displayed in a small fraction of Device 2-containing cells. </p> |

| - | + | <br style="clear:both" /> | |

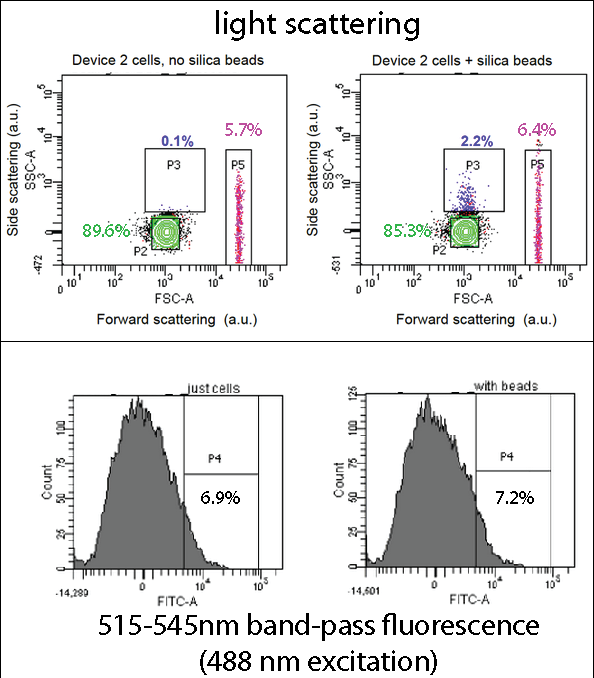

| - | + | ===Flow Cytometry=== | |

| - | <br style="clear:both"/> | + | [[File:Leeds FACS Overall Information Pic.png|center|800px|annotation, click to view full image|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/be/Leeds_FACS_Overall_Information_Pic.png|frameless]]<p align="justify">[[Team:Leeds/Project#Device 2|Device 2]] contains our [[Team:Leeds/Parts|INP+Si4]] construct, along with the pCpxR-controlled GFP gene. Cells expressing this device were grown overnight, incubated with 5 micron diameter silica beads for two hours, and then analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD Fortessa instrument (at the Leeds Flow Cytometry Facility). The light scattering flow cytometry data shown here provides a map (a 2-dimensional histogram) of light scattering intensities caused by each bead or cell particle flowing past the cytometer's interrogating laser, with scattering from 10,000 particles mapped in each plot shown. Side scattering and forward scattering properties are related to the size and density of the scattering particles. Boxes (“gates”) drawn in the scattering plots highlight certain sub-populations of the cells and cells+bead samples. Overall, the scattering distributions are very similar, suggesting that the beads and cells mainly reside in the same area of the plot (“P2”, green). However, in the cells+beads sample a small sub-population (2.2%) exhibits increased side-scattering (“P3”), likely stemming cell-bead complexes and thus indicating bead binding by the cell. (Gate P4 may be due to impurities or salt precipitates in the growth media.) |

| - | === | + | <br><br> |

| - | [[File:Leeds FACS Overall Information Pic.png|center|800px|annotation, click to view full image|link=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/be/Leeds_FACS_Overall_Information_Pic.png|frameless]]<p align="justify">Device 2 contains our INP+Si4 construct, along with the | + | Thus, overall, a small population of the cells seems to display function Si4 binding peptides, agreeing with the relatively few number of silica-coated cells found in our mineralization assay, and the relatively frequency of highly fluorescing, silica-binding (Device 2-expressing) cells observed via confocal fluorescence imaging. |

| - | <p align="justify">In the assay containing Device 2 with beads, there was an increase in the percentage of Population 3 (coloured in blue), from 0.1 to 2.2. This is suggestive of representing our Device 2 cells bound to silica beads. In contrast, the assay, which contained only Device 2 cells, had | + | <br><br> |

| - | <p align="justify">This suggests that our Device may successfully be binding to the silica beads utilizing the INP+Si4 construct, however not in all cases. This could either be due to not having enough time for | + | The fluorescence data is presented as a one-dimensional histogram and shows the same population as that plotted in the corresponding light-scattering maps. This data shows a very slight increase in the fraction of highly fluorescent particles, which could possibly correspond to the P3 gated population. |

| - | <br style="clear:both/> | + | <br><br> |

| + | Overall, these data indicate that in future work may want to focus on cell surface display binders that are either more readily expressed or exhibit better target-binding properties versus the Si4 silica-bindin peptide explored here. While a relatively small fraction of cells binds to target beads, this still us allowed to demonstrate the feasibility of our detection approach, which is a significant result (see confocal data). | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p align="justify">In the assay containing Device 2 with beads, there was an increase in the percentage of Population 3 (coloured in blue), from 0.1 to 2.2. This is suggestive of representing our Device 2 cells bound to silica beads. In contrast, the assay, which contained only Device 2 cells, had an insignificant percentage of Population 3 (0.1%).</p> | ||

| + | <p align="justify">This suggests that our Device may successfully be binding to the silica beads, utilizing the INP+Si4 construct, however not in all cases. This could either be due to not having enough time for binding totake place, or that our Si4 binding domain is not as effective as it should be - due to either under expression, or a weak binding domain.</p> | ||

| + | <br style="clear:both" /> | ||

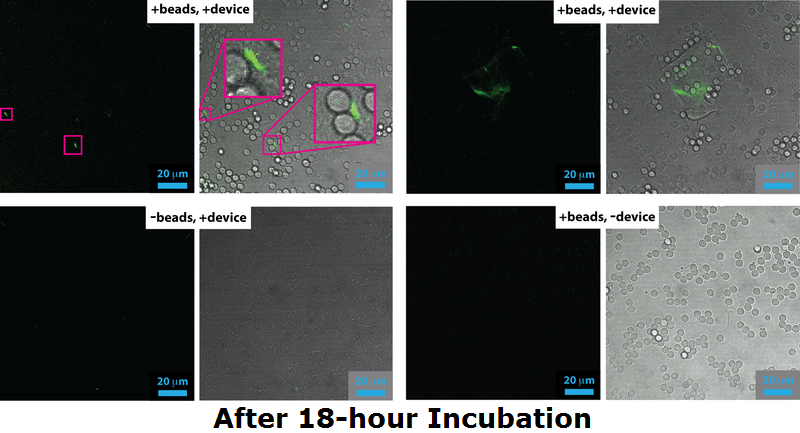

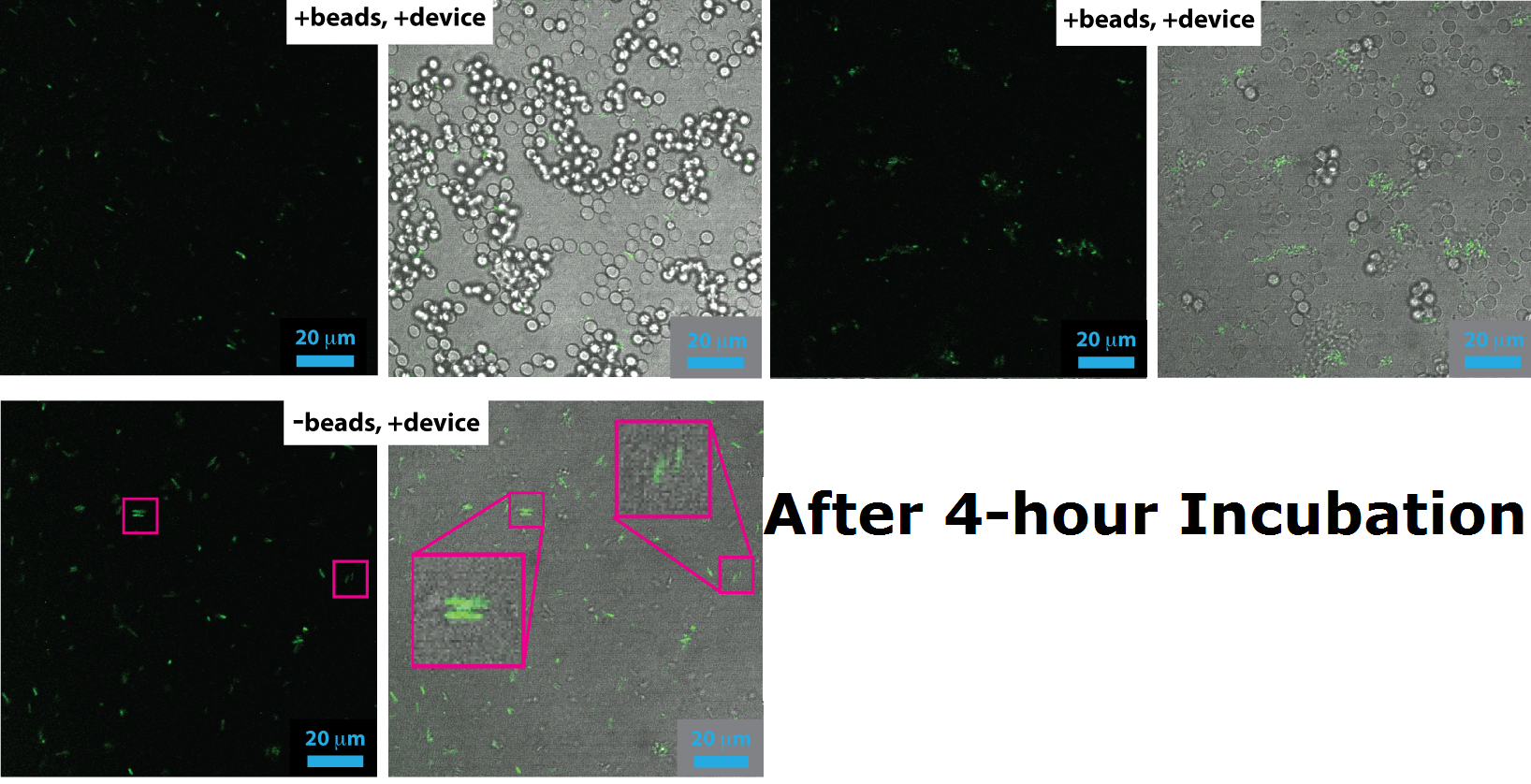

| + | ===Confocal Microscopy=== | ||

| + | <div><div id="touchgallery1" class="touchgallery"> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>[[File:IGEM confocal data 18 h-01.png|center|750px|Confocal image, after 18h incubation|frameless]]</li> | ||

| + | <li>[[File:Leeds confocalmicroscopyimage1.png|center|750px|Confocal image, after 4h incubation|frameless]]</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </div></div><p align="justify"> | ||

| + | Cells expressing Device 2 (which includes both pCpxR+GFP and INP+Si4) were grown either overnight (18 h) or to mid-log phase (4 h) either in the presence of 5 micron diameter beads or without beads present. Cells and/or beads were then analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy, the results of which are shown here. For each panel, the image on the left is a fluorescence image acquired through a 500 nm long-pass filter under 488 nm excitation and the images on the right is the corresponding bright field image that has been overlaid with the fluorescence image. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | For cells grown to the mid-log phase (5 h), GFP expression resulting from pCpxR activation is observed in both in the -beads control sample as well as the +beads experimental sample. Dividing bacteria are highlighted in magenta in the confocal images for the 5 h -bead control sample, highlighting that the likely source of membrane stress and pCpxR activation at this growth stage: membrane dynamics associated with cell replication. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | At 18 h incubation relatvely little GFP expression is observed in the both the +bead experimental sample and -bead control sample. However, in the +bead experimental sample has higher levels of GFP expression and highly fluorescent cells are occasionally observed bound to the surface of the silica microbeads (magenta highlights in the +beads, +device sample). The low fraction of observed successful devices is probably due to issue with the Si4 binding, a conclusion that agrees with both flow cytometry, which showed only 2% binding, and SEM, which yielded only a few cases of mineralized cells. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | We note apparent biofilm formation (including pCpxR activation) in both the 5 h (bottom row) and 18 h (top right panel) samples. This could be related to device-induced binding, but requires further exploration in future work. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br style="clear:both" /> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 03:58, 5 October 2013

Data shown here provide evidence that our MicroBeagle strategy is feasibly, but that optimization is required in order to achieve improved expression of cell surface displayed target-binding proteins, and to modify the level of the stress-responsive promoter activation to make it operable over larger growth regimes. The current version (v1) of MicroBeagle is only effective at late growth stages.

Bacterial growth curvesWe are monitoring the growth of our bacteria containing our devices to see if the genes we inserted have any effect on bacterial growth. Control Bacterial Growth CurveTo kickstart lab work for Leeds's first-ever iGEM team, we performed this straightforward experiment in which cells were grown in SB media both in the presence and absence of chloramphenicol. Absorbance measurements taken over time show the growth of the bacteria. Clear lag and log phases are observed when the bacteria are grown in SB media only. But as expected, the graph shows that the bacteria do not grow in the presence of chloramphenicol. This graph was use as a control to compare with device-containing bacteria in order to determine whether the genes we inserted caused an effect on cell growth.

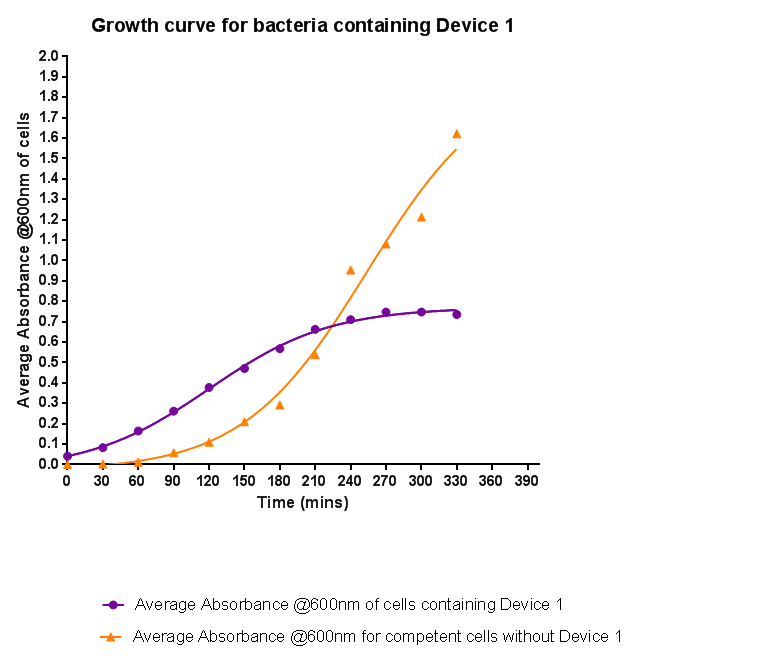

Characterisation of Device 1Growth CurveBacteria were grown which contained Device 1; their absorbance was monitored over time and then the rate of growth compared to bacteria that do not contain Device 1. The graph clearly shows that inserting Device 1 into cells considerably slows their growth in log phase compared with the growth of cells without Device 1, that the lag phase is shorter, and that the cells don't grow to as high an optical density in log phase as the bacteria without Device 1.

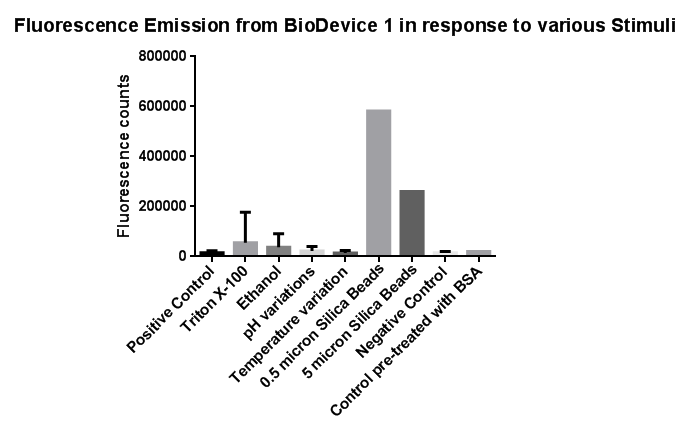

Membrane StressInvestigation of literature regarding the action and regulation of the Cpx pathway lead to the discovery that the system as a whole responds to a large variety of membrane stresses, something that could be true of the specific promoter we chose to use (pCpxR). We therefore sought to investigate the response of our promoter to each individual membrane stress. Individually many of the experiments produced erratic and seemingly random data which is listed independently below. However plotting all average readings together shows that there is a dramatic increase in response to the stress induced by the silica beads relative to all chemically induced membrane stresses tested. This indicates that it would be possible to detect the presence of silica beads in solution, in principle, using our binding and detection system. This was certainly successful when silica beads were present at relatively high concentrations. However further work needs to be done to assess whether this high response remains across a range of silica bead concentrations in solution. In light of these results, additional experiments were conducted to gain further information in which cells were exposed to the stresses of ethanol, Triton X-100 and pH gradients. In this second experiment, a robotic pipette was used to directly fill the 96 well plate to reduce human error, the raw data of which can be found here. Excluding wells with imposed pH gradient, all wells were kept at pH 7 using Tris.HCl buffer, the pH gradient was also achieved with a Tris.HCl buffer. The 96 well plates (200 microliters/well), prepared with the chemical stressors, were inoculated with 20 microliters of overnight cell culture expressing Device 1 and incubated with shaking for 2 hours at 37 degrees. We also performed preliminary investigation on the effects of temperature extremes on the CpxR promoter but the results were inconclusive and thus warrant further studies, possibly by future Leeds iGEM teams. Listed below is the data for detergent and pH extremes. We note that the response of the Cpx pathway to temperature has been characterized previously in the literature and by Calgary 2010.

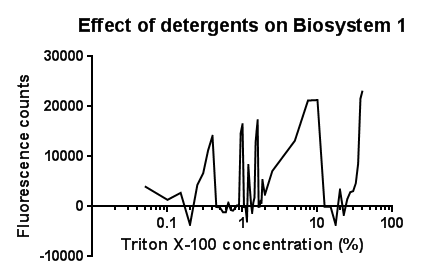

Triton X-100Between the concentration values of 0.1-9.0% triton X-100, the data shows roughly the relationship that was expected, a rise in GFP production as the triton concentration increases. This is likely due to triton acting as a detergent resulting in damage to the plasma membrane of cells, activating the Cpx pathway in general, including the CpxR promoter (pCpxR). Past 10% Triton X-100 concentration, it is assumed that cells are dying in large quantities, being unable to produce GFP at all or in very limited amounts before they are killed. This explains the corrected fluorescence readings reducing to below zero. The reason for the large spike in fluorescence at Triton concentrations >20% is unclear, a possible explanation for this is the total lysis of the cell, expelling all cellular components resulting in background GFP levels having a larger fluorescence reading due to reduced scattering from within the cell. It is most important to note that this is preliminary data, from fluorescence based measurments, hence it is expected that with sufficiently high repeat readings, the trends proposed will clarify further. This would again be suggested extension work for future teams.

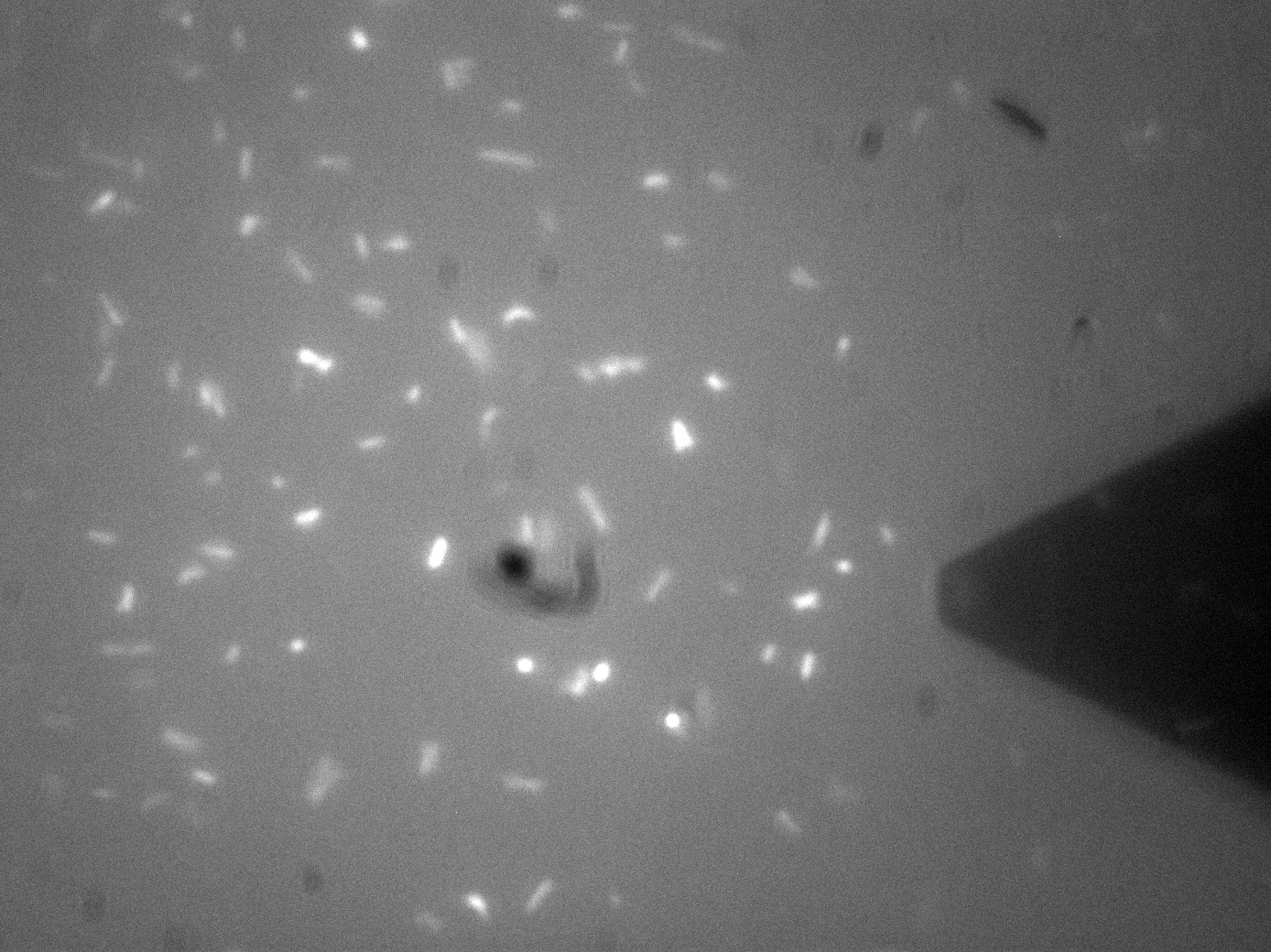

Membrane Stress - (Fluorescence) Atomic Force MicroscopyAtomic Force Microscopy utilises Van-Der-Waals forces to attract the tip towards a surface, causing the bending of a cantilever, onto which a laser is pointed. The tip deflection causes the laser light to also be deflected and this is tracked using a bank of photodiodes. AFM is typically used to image surfaces at the atomic scale, as well as for Force Spectroscopy. When used in Force Spectroscopy, the tip is brought into direct contact with the sample, allowing the sample protein to bind to the silicon tip. Then, the AFM is slowly retracted at varying speeds or to varying distances, applying a force to the protein. This causes portions of the protein to unravel, and the distinct patterns associated with α-helices and β-pleated sheets can be seen in this data. This allows the exact secondary and tertiary structure of a protein to be determined, but also the energy profile of various conformations, which in turn tells us how the protetin folds. For Bio-Device 1 however, the team wanted to measure how much force was required to trigger the stress activated Cpx Pathway. This was to be done by observing the culture under the fluoroscope portion of the F-AFM, and then "prod" a bacterium at a low force, slowly increasing the stress until a fluorescence response was seen. This would then give a direct measure of the stress threshold for Cpx, a value currently unknown in the literature. This is however, distinctly more difficult that it sounds. Firstly, it can be seen from the image that the culture were already fluorescing a little, likely due to smaller stresses in solution, although some can clearly be seen in the middle of binomial fission, which is known to also activate the pathway. The other issue was with trying to keep the bacterial cells stable enough to continually poke them with AFM tip. Normally, this sort of experiment is typically performed at the Univ of Leeds AFM facility on Giant Unilamellar Vesicles and microbubbles about 5 microns wide. These microstructures are naturally forming precursors to cells, and thus of great interest to bio-physicists. However, as trying to poke a structure 5 microns wide with a tip only 40nm at its widest is akin to throwing a needle from space onto a ship in the Atlantic ocean, experimenters usually adhere the bubbles to the surface with a binding peptide. This could not be done for Bio-Device 1 without potentially triggering the pathway, so instead, it was hoped a more viscous solution and some micro-troughs scratched into the glass slide surface would be enough to keep them steady. Again though, bacteria are very different to inert bubbles of lipids, and tend to forcibly move themsleves regardless, hence results remained inconclusive. The approach showed some promise however, and it is hoped further work will be undertaken on this at a later date. The presence of background fluorescence in this experiment agrees with fluorescence confocal data and previous literature suggesting that the pCpxR promoter is active during early and mid-log phase of cell growth (cell division). Again, we are interesting in the possibility of using evolutionary development techniques to mutate a variant promoter, specific for MicroBeagle activity, with a higher threshold stress tolerance than the native Cpx promoter. Other extensions to this work would be in use of characterising the binding domain strengths of MicroBeagle, and we hope other teams may seek to use similar methods in future.

Characterisation of Si4 silica-binding oligo-peptideGrowth CurveHere the growth of cells expressing INP-displayed Si4 was monitored via absorbance and compared to the growth of cells that do not contain Si4. As was seen when device 1 was inserted into the cells, the growth is slowed down considerably. Although the graph shows a log and a lag phase for the cells expressing INP-Si4, the absorbance reached in log phase is very low compared to cells without Si4; it is even lower than the absorbance reached for cells containing Device 1.

Characterisation of Device 2Growth CurveThis graph shows the results of monitoring the growth of cells with expressing Device 2. As with other hetereologous expression experiments, growth of the cells is considerably slowed when compared with cells that do not contain any device at all. A slight change in the gradient of the graph can be seen showing the transition of the cell growth from lag to log phase, so the cells are still growing normally, but the insertion of Device 2 is restricting rate of cell growth and final density acheived. We propose that this is due to the increased energy and nutrient requirements to produce the inserted structures.

Scannning Electron Microscopy

The gallery above contains Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) data on cells either expressing Device 2 (i.e. displaying Si4), or not (control). Cells were grown overnight and then incubated with 1 mM silicic acid (formed by acid hydrolyzing 1 mM tetraethoxysilane), pelleted by centrifugation and then imaged by SEM, which chemical analysis by electron x-ray dispersive spectroscopy (EDX). Only in the cell samples containing Device 2 were silica-coated cells observed, whereas in the control cell population no cells coated with large quantities of silica were observed. Silica formation is expected to occur through reaction of surface-displayed Si4 with silicic acid in solution. The silica-coated cells shown here were relatively few in the overall population of experimental (Device 2-containing) cells, with large number of experimental cells uncoated. However, no cells in the control were found to be similarly coated by silica. Collectively, these data suggest that Si4 is effectively surface-displayed in a small fraction of Device 2-containing cells.

Flow CytometryDevice 2 contains our INP+Si4 construct, along with the pCpxR-controlled GFP gene. Cells expressing this device were grown overnight, incubated with 5 micron diameter silica beads for two hours, and then analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD Fortessa instrument (at the Leeds Flow Cytometry Facility). The light scattering flow cytometry data shown here provides a map (a 2-dimensional histogram) of light scattering intensities caused by each bead or cell particle flowing past the cytometer's interrogating laser, with scattering from 10,000 particles mapped in each plot shown. Side scattering and forward scattering properties are related to the size and density of the scattering particles. Boxes (“gates”) drawn in the scattering plots highlight certain sub-populations of the cells and cells+bead samples. Overall, the scattering distributions are very similar, suggesting that the beads and cells mainly reside in the same area of the plot (“P2”, green). However, in the cells+beads sample a small sub-population (2.2%) exhibits increased side-scattering (“P3”), likely stemming cell-bead complexes and thus indicating bead binding by the cell. (Gate P4 may be due to impurities or salt precipitates in the growth media.)

In the assay containing Device 2 with beads, there was an increase in the percentage of Population 3 (coloured in blue), from 0.1 to 2.2. This is suggestive of representing our Device 2 cells bound to silica beads. In contrast, the assay, which contained only Device 2 cells, had an insignificant percentage of Population 3 (0.1%). This suggests that our Device may successfully be binding to the silica beads, utilizing the INP+Si4 construct, however not in all cases. This could either be due to not having enough time for binding totake place, or that our Si4 binding domain is not as effective as it should be - due to either under expression, or a weak binding domain.

Confocal Microscopy

Cells expressing Device 2 (which includes both pCpxR+GFP and INP+Si4) were grown either overnight (18 h) or to mid-log phase (4 h) either in the presence of 5 micron diameter beads or without beads present. Cells and/or beads were then analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy, the results of which are shown here. For each panel, the image on the left is a fluorescence image acquired through a 500 nm long-pass filter under 488 nm excitation and the images on the right is the corresponding bright field image that has been overlaid with the fluorescence image.

| |||||||

|

| ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

"

"