Team:British Columbia/Modeling

From 2013.igem.org

(→Viral Growth) |

Ym10201002 (Talk | contribs) (→==) |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b2/UBC_Model-PhageControl.png" width="500px"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b2/UBC_Model-PhageControl.png" width="500px"> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <br/><b>Figure 1:</b> | + | <br/><b>Figure 1:</b> Schematic of the model system where both strains are immunized against common environmental phages and the abundance of one can be modulated by the addition of a control phage. |

</div> | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

V = V_0 + E(X_i)\beta^{\big[\frac{t}{LT}\big]} | V = V_0 + E(X_i)\beta^{\big[\frac{t}{LT}\big]} | ||

\end{align} | \end{align} | ||

| - | Where $E(X_i)$ is the expected infected population and $\big[\frac{t}{LT}\big]$ is the largest integer equal or less than $\frac{t}{LT}$. To find the expected infected population, the Poisson distribution is used based on the MOI (multiplicity of infection - defined as the ratio of phage to bacteria) | + | Where $E(X_i)$ is the expected infected population and $\big[\frac{t}{LT}\big]$ is the largest integer equal or less than $\frac{t}{LT}$. To find the expected infected population, the Poisson distribution is used based on the MOI (multiplicity of infection - defined as the ratio of phage-to-bacteria), with a term for efficiency of viral attachment $\epsilon \in (0, 1)$ (in fact the efficiency has been found to be a function of certain proteins) [4,5]. |

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

===Substrate Utilization=== | ===Substrate Utilization=== | ||

| - | + | Bacteria require a substrate for growth, and the depletion of this substrate is proportional to the growth rate of the uninfected bacteria and the amount of bacteria. Although the infected bacteria do not multiply when infected, the infected cells may consume substrate to generate energy needed to replicate the phage. Although it may be the case that the bacteria simply recycle intracellular material, a substrate utilization term ($\gamma$) for the infected cells is added (if the bacteria do in fact recycle intracellular material, it follows that this value will be 0). Moreover, when cells lyse, the re-solubilized cytoplasmic contents can be metabolized by other bacteria and will add to the amount of nutrients available. Thus, the equation for substrate utilization rate is: | |

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

===Extending to Co-culture=== | ===Extending to Co-culture=== | ||

| - | The end goal of our project is to tune product formation of two or more compounds by adding phage to a batch reactor. Our extension to co-cultures considers the situation where vanillin and cinnamaldehyde strains have both been engineered with | + | The end goal of our project is to tune product formation of two or more compounds by adding phage to a batch reactor. Our extension to co-cultures considers the situation where vanillin and cinnamaldehyde strains have both been engineered with "CRISPR immunity" to an environmental phage. Additionally, the vanillin producing strain has been engineered with immunity to a control phage, whereas the cinnamaldehyde is susceptible. Since both strains contain the CRISPR assembly and an engineered metabolic pathway, it is not entirely unreasonable to assume that their growth rates are similar. Let our bacterial cultures be $X$ for cinnamaldehyde and $Z$ for vanillin. Our equations become: |

<html> | <html> | ||

| Line 195: | Line 195: | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <html><p>We use Matlab to solve this system of equations. This model | + | <html><p>We use Matlab to solve this system of equations. This model demonstrates how phage can be used to control product formation. However, to know whether or not the model is representative of our systems behaviour, we must first have a qualitative understanding of our expected results. As the initial MOI increases, the cinnamaldehyde producing strain (susceptible to control phage infection) will collapse faster than at a lower MOI. If we assume that the production rates of vanillin and cinnamaldehyde equal during growth without phage, then we expect the product formation curves to separate with increasing MOI. Figure 5 shows that our model, run at two different MOI's (two orders of magnitude apart), predicts the qualitative trends we were expecting to see. |

</p> | </p> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| Line 208: | Line 208: | ||

==Probabilistic Model== | ==Probabilistic Model== | ||

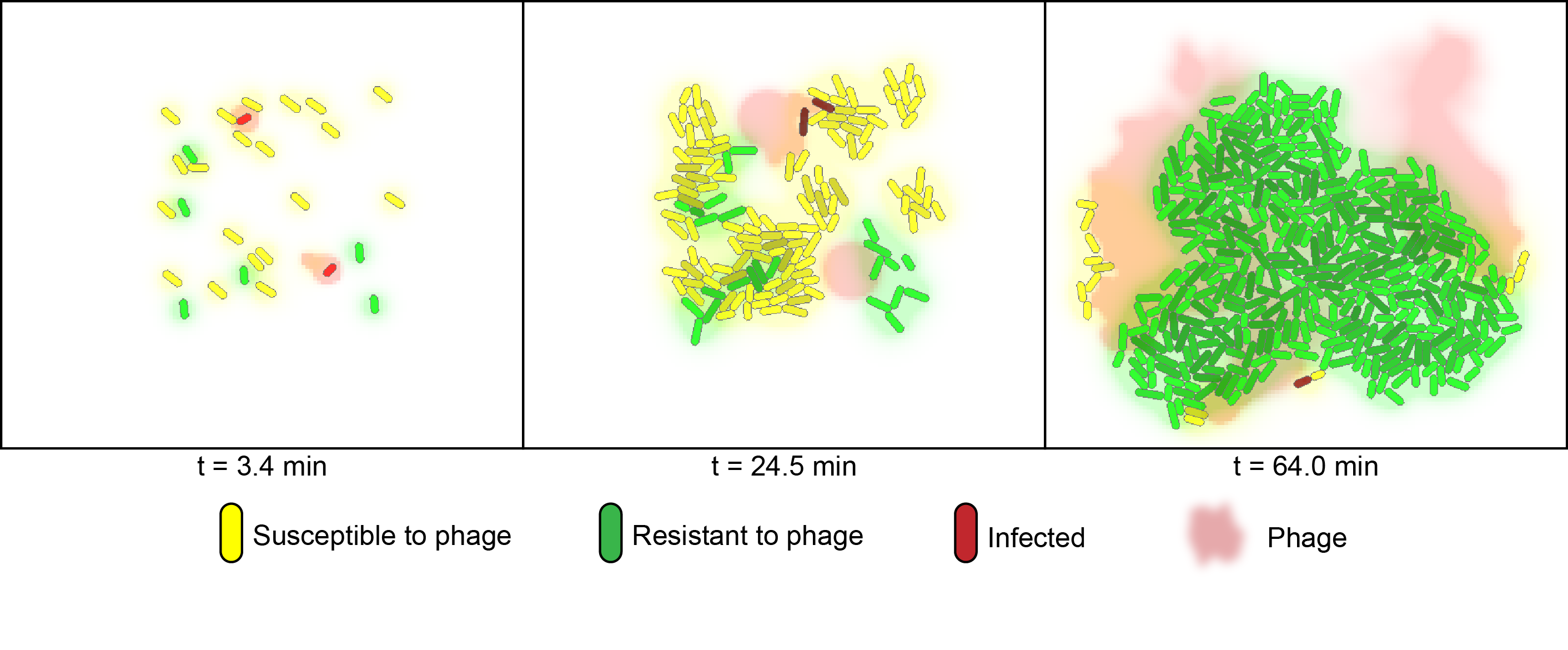

| - | For the | + | For the probabilistic simulation of co-cultures we utilized the cell programming language gro, which was developed by the Klavins Lab at the University of Washington [2]. The model considers two strains of bacteria on a two-dimensional plane under attack of one virus. One strain (green) contains a specific spacer element for the "control" phage and is granted immunity, whereas the other strain (yellow) is susceptible to phage infection. In the simulation, susceptible bacteria entering regions with high phage concentrations are very likely to become infected and upon lysis increase the phage concentration of that region. Below is a timeseries illustrating the control of susceptible cells with phage addition over the course of one batch cycle. Here, the amount of viable susceptible cells remaining over time can be controlled by adjusting the starting phage-to-bacteria ratio, allowing for optimal product formation. |

<center> | <center> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:49, 7 August 2014

iGEM Home

Population Dynamics Modeling

Figure 1: Schematic of the model system where both strains are immunized against common environmental phages and the abundance of one can be modulated by the addition of a control phage.

Mixed cultures are often used in bioprocessing, where the quality of the final product requires optimal strain balance. We realized that mixed cultures harbouring different CRISPR assemblies could be modulated by applying selective pressure against targeted strains via phage addition. This provides a novel opportunity for tuning bacterial consortia, directly applicable to industrial bioprocesses such as yogurt production that rely on mixed culture fermentation. Here, we develop deterministic and probabilistic models to provide a predictive framework for optimizing strain balance within mixed populations. We then extend this model to allow for optimization of product formation, such as flavouring of yogurt.

Our main objectives were to:

- Predict the growth of mono- and mixed- recombinant E. coli cultures under phage predation.

- Predict vanillin and cinnamaldehyde production based on initial ratio of phage-to-bacteria, (ie. multiplicity of infection; MOI).

The schematic for the final model is illustrated in figure 1. We considered two E. coli strains, each harbouring two plasmids: a flavouring plasmid and a CRISPR (or "immunity") plasmid. Here, the flavouring plasmid is responsible for the production of either cinnamaldehyde or vanillin and the CRISPR plasmid contains unique spacer elements, granting both strains immunity against "environmental phage" that may contaminate the bioreactor. Additionally, one strain would be immunized against the "control phage", where the other strain would remain susceptible. This construction would allow us to tune the susceptible population in order to achieve our desired flavouring proportions, based on the amount of control phage added.

Model Formulation

Assumptions

- Bacteria are grown in a batch culture and follow the Monod growth equation.

- Bacteria harbouring the CRISPR assembly are 100% immune to the specific phage infection (based on spacer element).

- Bacteria without CRISPR system are completely susceptible to phage infection.

- Yield coefficients and phage attachment coefficients are constant.

- Bacteriophage do not decrease significantly in number during the course of an experiment.

- All considered bacteriophages are lytic.

Deterministic Model - modeling bacterial growth under phage predation

A deterministic model based on Monod kinetics [1] was used to describe bacterial growth. Here, the Poisson distribution was incorporated to model the infected populations based on a starting phage-to-bacteria ratio, or MOI. We trained the model on a set of experimental growth curves and validated it against a separate set. Yield terms were added to account for the production of two different flavours: cinnamaldehyde and vanillin. Next, we extended our basic growth model to include bacterial co-cultures. Using this approach, we demonstrate that by using different virus inoculums, it is possible to achieve different final amounts of compounds from a mixed culture.

Bacteria Growth

We begin with a populations balance for a given strain $X$, \begin{align} \frac{dX}{dt} = \frac{dX_i}{dt} + \frac{dX_u}{dt} \end{align} The infected bacteria is represented by $X_i$, uninfected bacteria by $X_u$ and $X = X_i + X_u$. We use the Monod equation to model the substrate limited bacterial growth. \begin{align} \mu_{X} = \mu_{max, X} \frac{S}{K_{S, X} + S} \end{align}

Where $\mu_{X}$ is the bacterial growth rate, $\mu_{max, X}$ is the maximum bacterial growth rate, $S$ is the growth limiting substrate and $K_s$ is the amount of substrate remaining when the growth rate is half of maximum. Due to environmental factors, some bacteria will die; the death rate ($k_d$) is assumed to be directly proportional to the bacteria population. A lag phase is modelled by multiplying a dampening term to the growth rate, namely $(1 - e^{-\alpha t})$, where $\alpha$ is defined as a proportionality constant. The slowing of growth from exponential to stationary is modelled with yet another dampening term to be multiplied to the growth: $exp\big[{-\big(\frac{X}{X_c}\big)^m\big]}$. This dampening term is related to the quorom sensing in bacteria; once the bacteria reach some characteristic concentration ($X_c$) the bacteria begin to slow down growth. Thus the uninfected cell growth is described by: \begin{align} \frac{dX_u}{dt} = \big( \mu_{X, u}e^{-\big(\frac{X}{X_c}\big)^m} - k_{d_{X,u}} \big) X_u\big(1 - e^{-\alpha t}\big) \end{align} For simplicity, in this model, $m$, $X_c$, and $\alpha$ are all to be empirically determined and assumed constant. In reality, each constant is dependent on many variables, for example: temperature, pressure, [substrate], environmental conditions, bacterial strain, and more. Similarly for infected cells: \begin{align} \frac{dX_i}{dt} = \big( \mu_{X, i}e^{-\big(\frac{X}{X_c}\big)^m} - k_{d_{X,i}} \big) X_i\big(1 - e^{-\alpha t}\big) - \delta \end{align}

However, a major difference is that the decay rate for the infected cells is dependent on the latency time of the virus and thus we introduce $\delta$. The function $\delta$ is defined as follows,

Here, $N(\tau)$ is a normal distribution over some time $\tau$, in other words, it is expected that the infected population will lyse according to a normal distribution over the domain $(-\tau, \tau)$.

Viral Growth

It is now necessary to consider the phage population $V$ as it directly affects the amount of bacteria that are infected at any given time. To describe the phage population it is necessary to consider how many phage are released per cell lysis. This number is referred to as the burst size $(\beta)$. \begin{align} V = V_0 + X_i \beta ^{\frac{t}{LT}} \end{align} Where $V_0$ is the initial phage populations and $LT$ is the latency time (they time between infection and lysis). However, since it is difficult to measure the exact phage at various time points, as well as the exact amount of infected bacteria, it is desired to simplify the model. It is reasonable to use a stepwise function that describes the amount of free phage present. Also, since the burst size is large, on the order of $100$ [3], we see that the loss of current phage due to infection of cells is small (roughly 1%), thus to simplify computations we consider this to be negligible. With these deductions we arrive at the following: \begin{align} V = V_0 + E(X_i)\beta^{\big[\frac{t}{LT}\big]} \end{align} Where $E(X_i)$ is the expected infected population and $\big[\frac{t}{LT}\big]$ is the largest integer equal or less than $\frac{t}{LT}$. To find the expected infected population, the Poisson distribution is used based on the MOI (multiplicity of infection - defined as the ratio of phage-to-bacteria), with a term for efficiency of viral attachment $\epsilon \in (0, 1)$ (in fact the efficiency has been found to be a function of certain proteins) [4,5].

\begin{align} MOI = \frac{V}{X} \end{align}

\begin{align} E(X_i) = \epsilon X(1 - e^{-MOI}) \end{align}

Substrate Utilization

Bacteria require a substrate for growth, and the depletion of this substrate is proportional to the growth rate of the uninfected bacteria and the amount of bacteria. Although the infected bacteria do not multiply when infected, the infected cells may consume substrate to generate energy needed to replicate the phage. Although it may be the case that the bacteria simply recycle intracellular material, a substrate utilization term ($\gamma$) for the infected cells is added (if the bacteria do in fact recycle intracellular material, it follows that this value will be 0). Moreover, when cells lyse, the re-solubilized cytoplasmic contents can be metabolized by other bacteria and will add to the amount of nutrients available. Thus, the equation for substrate utilization rate is:

\begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} = - \big[ \frac{\mu_u}{Y_u}X_u + \frac{\gamma}{Y_i}X_i \big] + \phi \delta \end{align} Where $Y_u$ and $Y_i$ are yield constants and $\phi$ is the average amount of substrate released per infected cell during lysis, $\delta$ has as described above.

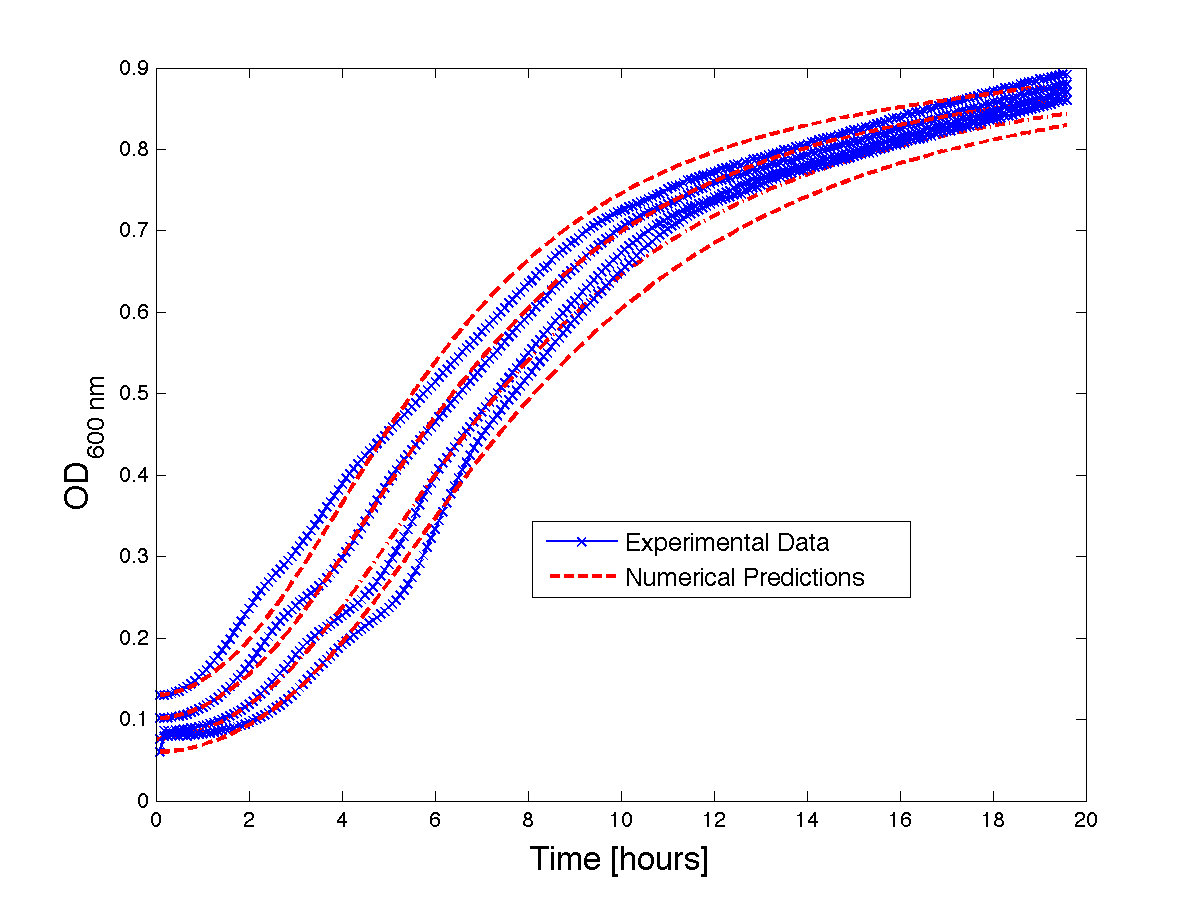

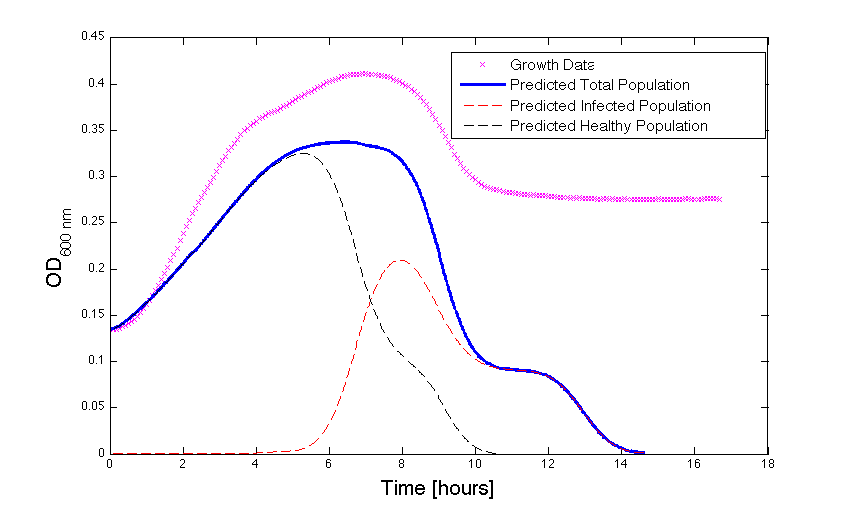

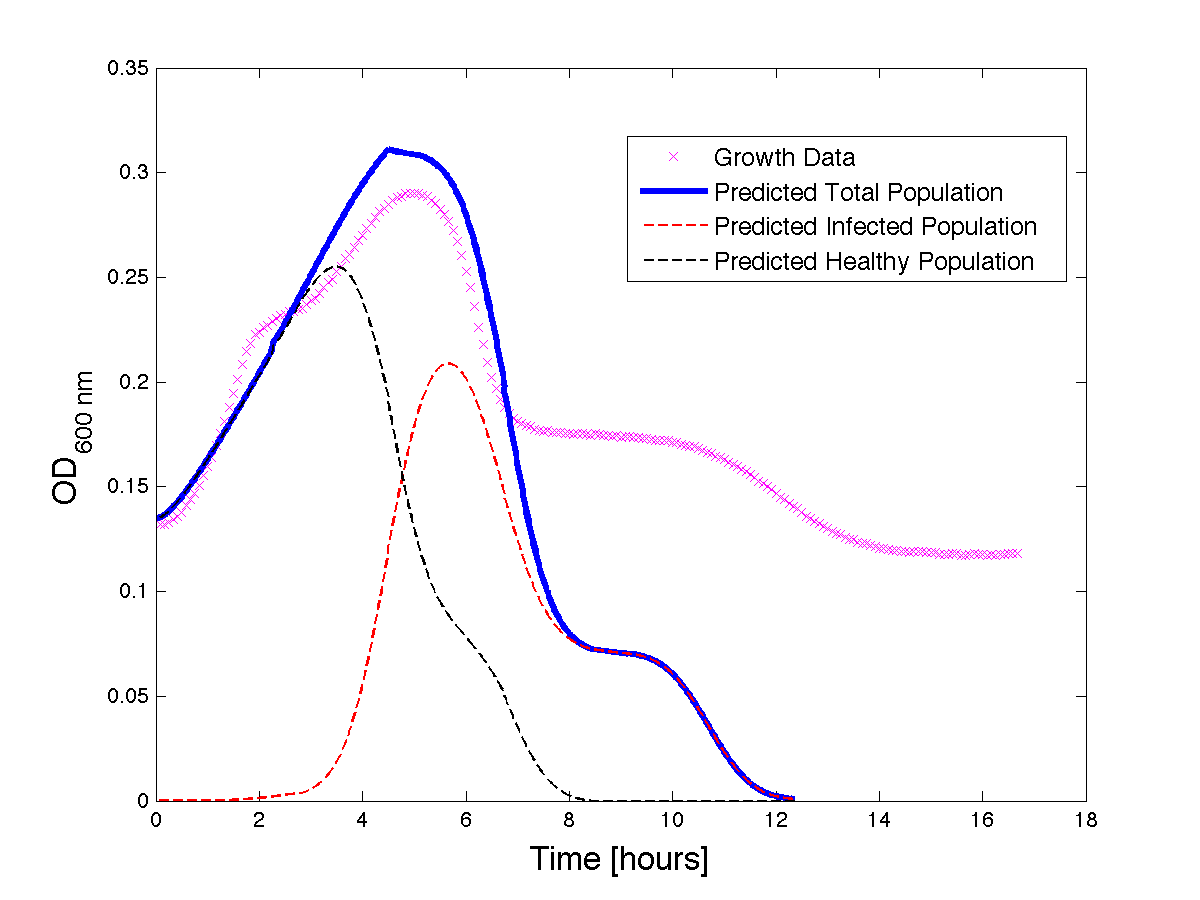

Model Validation

Although, only limited amounts of growth curves have been able to be analyzed, the quantitative results appear promising and the qualitative results have been found to contain information whether or not the quantitative results align.The model is shown to have powerful predictive capabilities when it comes to a bacteria growth curve not under phage predation.The model also appears to have powerful qualitative predictions for culture collapse under phage predation. However, consistent quantitative predictions for bacteria growing under phage predation has not yet been shown. Note: as time progresses OD measurements will pick up cellular debris (also referred to as "bacterial bones") which will artificially inflate the concentration of bacteria after lysis - by plating we confirm that the culture does not contain as many viable cells as the OD reads.

Figure 2 - Bacteria growth curves from lag phase to approaching stationary phase. The model was optimized on another set of data and was tested for validity on this set.

Figure 3 - Bacteria growth under phage predation. In models where the quantitative values differ, there is still qualitative information that can be extracted.

Figure 4 - A better fit for bacteria growth under phage predation. Also included are the predicted infected and uninfected populations.

Product Formation

For a given uninfected bacteria $X_u$ that can produce the product $P$, we will first expect the production rate to be first order equation: \begin{align} \frac{d[P]}{dt} = \frac{\mu_{X_u}}{Y_P}X_u \end{align} Where $Y_P$ is the yield coefficient of the product. For infected bacteria we expect the product formation rate to be negligibly small.

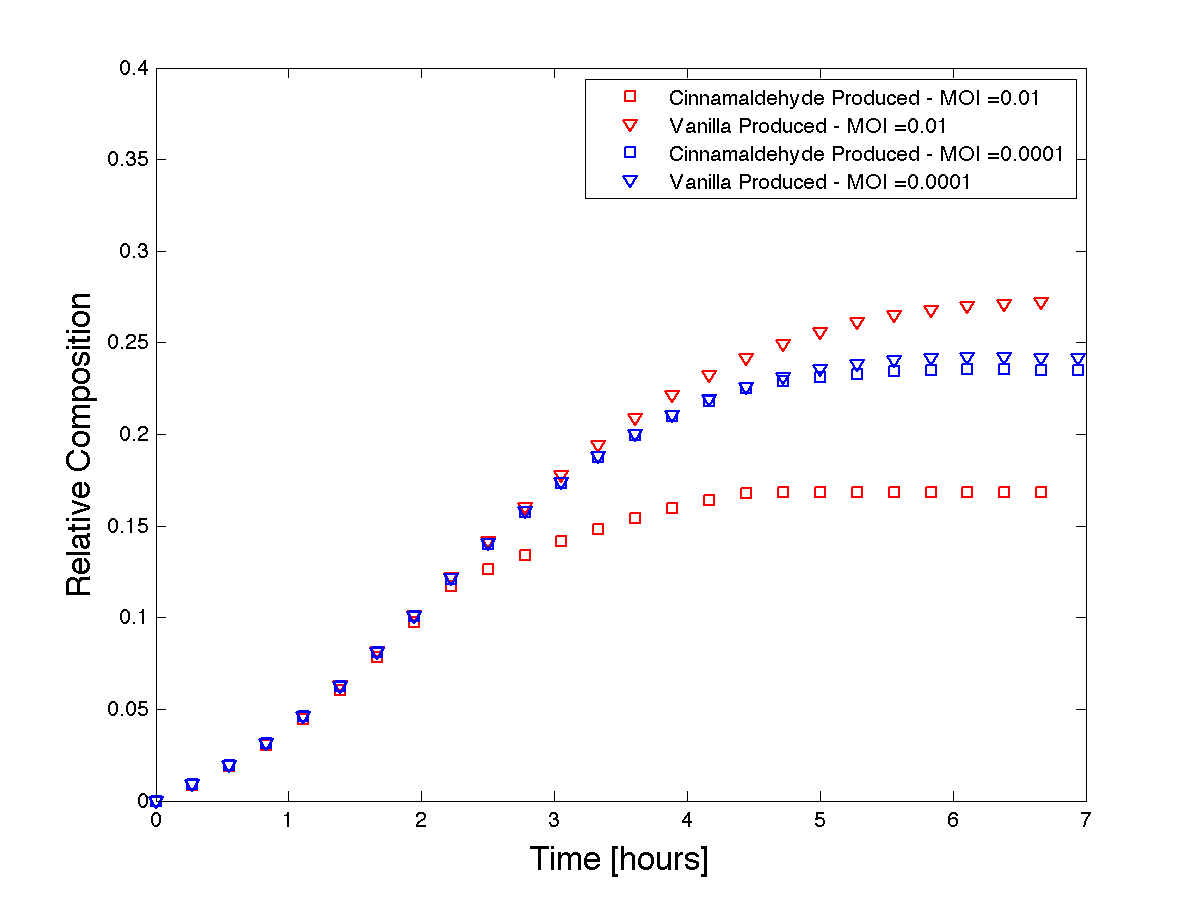

Extending to Co-culture

The end goal of our project is to tune product formation of two or more compounds by adding phage to a batch reactor. Our extension to co-cultures considers the situation where vanillin and cinnamaldehyde strains have both been engineered with "CRISPR immunity" to an environmental phage. Additionally, the vanillin producing strain has been engineered with immunity to a control phage, whereas the cinnamaldehyde is susceptible. Since both strains contain the CRISPR assembly and an engineered metabolic pathway, it is not entirely unreasonable to assume that their growth rates are similar. Let our bacterial cultures be $X$ for cinnamaldehyde and $Z$ for vanillin. Our equations become:

Subject to initial and boundary conditions:

We use Matlab to solve this system of equations. This model demonstrates how phage can be used to control product formation. However, to know whether or not the model is representative of our systems behaviour, we must first have a qualitative understanding of our expected results. As the initial MOI increases, the cinnamaldehyde producing strain (susceptible to control phage infection) will collapse faster than at a lower MOI. If we assume that the production rates of vanillin and cinnamaldehyde equal during growth without phage, then we expect the product formation curves to separate with increasing MOI. Figure 5 shows that our model, run at two different MOI's (two orders of magnitude apart), predicts the qualitative trends we were expecting to see.

Figure 5 - Theoretical product formations based on co-culture dynamics.

Probabilistic Model

For the probabilistic simulation of co-cultures we utilized the cell programming language gro, which was developed by the Klavins Lab at the University of Washington [2]. The model considers two strains of bacteria on a two-dimensional plane under attack of one virus. One strain (green) contains a specific spacer element for the "control" phage and is granted immunity, whereas the other strain (yellow) is susceptible to phage infection. In the simulation, susceptible bacteria entering regions with high phage concentrations are very likely to become infected and upon lysis increase the phage concentration of that region. Below is a timeseries illustrating the control of susceptible cells with phage addition over the course of one batch cycle. Here, the amount of viable susceptible cells remaining over time can be controlled by adjusting the starting phage-to-bacteria ratio, allowing for optimal product formation.

The video of the above simulation is presented below:

Model Formulation: Joel Kumlin, Chris Lawson, Joe Ho

References

[1] Shuler, M.L. & Kargi, F. (2002). Bioprocess Engineering: Basic Concepts (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

[2] Jang, S.S., Oishi, K.T., Egbert, R.G., & Klavins, E. (2012). Specification and simulation of multicelled behaviors. ACS Synthetic Biology 1 (8), pp 365–374.

[3] Simon, E. H., Tessman, I. (1963). Thymidine-requiring Mutants of Phage T4. PNAS, 50, 526–532.

[4] Storms, Z. J., Arsenault, E., Sauvageau, D., & Cooper, D. G. (2010). Bacteriophage adsorption efficiency and its effect on amplification. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 33(7), 823–31.

[5] Storms, Z. J., Smith, L., Sauvageau, D., & Cooper, D. G. (2012). Modeling bacteriophage attachment using adsorption efficiency. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 64, 22–29.

"

"