Team:TU-Munich/Results/Summary

From 2013.igem.org

ChristopherW (Talk | contribs) (→Localization of effector proteins) |

ChristopherW (Talk | contribs) (→Implementation) |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

==BioDegradation== | ==BioDegradation== | ||

[[File:TUM13_EreB_LCMS.png|thumb|right|350px|'''Figure 2''': Degradation of erythromycin by recombinant protein and our PhyscoFilter [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/GM-Moss#The_PhyscoFilter_for_Erythromycin read more].]] | [[File:TUM13_EreB_LCMS.png|thumb|right|350px|'''Figure 2''': Degradation of erythromycin by recombinant protein and our PhyscoFilter [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/GM-Moss#The_PhyscoFilter_for_Erythromycin read more].]] | ||

| - | Under the headline [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Project/Biodegradation BioDegradation] we investigated effector proteins which degrade pollutants by enzymatic catalysis. For this purpose we introduced the new | + | Under the headline [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Project/Biodegradation BioDegradation] we investigated effector proteins which degrade pollutants by enzymatic catalysis. For this purpose we introduced the new BioBrick '''Erythromycin Esterase (EreB)''' which degrades macrolide antibiotics. Additionally we used well established BioBricks for BioDegradation. We improved the Laccase from ''Bacillus pumilus'', established by the iGEM Team of Bielefeld in 2012, by converting it to RFC[25] in order to be able to fuse it to the extracellular domain of our receptor. Both enzymes were produced as recombinant proteins and purified. Enzymatic characterization was carried out concerning salt tolerance, substrate and pH dependence. For the laccase temperature dependence and the half-life in river water was additionally estimated. All data was fitted in our enzyme kinetic modeling. The aim was to analyze this data and to provide a solid base for our filter calculator. This calculator uses all the data produced in our enzyme characterization to extrapolate from them for the large scale implementation of transgenic PhyscoFilters in waste water treatment plants or on rivers. We assumed the secretory production of laccase by our moss as the laccase degrades a wide variety of important pollutants such as the pain killer diclofenac, the oral contraceptive ethinylestradiol or iodined x-ray contrast media. All these substances are present in nature and are hardly degradable by conventional methods. While using [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Modeling/Filter this calculator for modeling], we learned that factors such as the degree of pollution in rivers, the average temperature in a specific country, the enzyme half-life time, as well as the actual amount of secreted protein play an important role for the efficacy of our PhyscoFilter. Generally the results show that approximately an area of 20 football fields would be required to produce enough laccase to reduce the contamination of the large river Rhein with the mentioned pharmaceutical compounds, while half a field would suffice for a large waste water treatment plant. Beside this result we also produced several different stable transgenic moss lines for our BioDegradation module and were able to show that our cytoplasmically expressed Erythromycin Esterase B enables our moss to successfully degrade the macrolide antibiotic Erythromycin. This experiment was analyzed by using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS). It worked for the recombinant protein as well as for the transgenic plant giving the [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/GM-Moss '''proof of principle''' for ''Physcomitrella patens'' as a bioremediation organism]. |

==BioAccumulation== | ==BioAccumulation== | ||

<html><iframe style="box-shadow: 1px 1px 2px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.2);padding: 5px;margin: 0px 0px 20px 20px;background-color: white;float: right;" src="http://player.vimeo.com/video/77974681" width="400" height="255" frameborder="0" webkitAllowFullScreen mozallowfullscreen allowFullScreen></iframe></html> | <html><iframe style="box-shadow: 1px 1px 2px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.2);padding: 5px;margin: 0px 0px 20px 20px;background-color: white;float: right;" src="http://player.vimeo.com/video/77974681" width="400" height="255" frameborder="0" webkitAllowFullScreen mozallowfullscreen allowFullScreen></iframe></html> | ||

| - | Beside the enzymatic degradation of pollutants we found different methods to bind them on our moss filter. We called this system [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Project/Bioaccumulation BioAccumulation]. The most obvious idea was to use binding proteins which were developed for human therapy, such as antibodies, for example. To investigate this idea we used an alternative binding protein, the Anticalin, which was engineered to bind fluorescein as it has a very high affinity, a small size and a robust fold [[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16307475 Vopel et al., 2005]]. Beside this engineered binding protein, we also recognized the idea of [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Team/Collaborations#Collaboration%20with%20Dundee%20iGEM%20team%202013 Dundee iGEM 2013] which sounded quite interesting. This team used a protein which is found in the toxicity mechanism of microcysteins. Dundee wanted to use it as a binding partner to absorb the pollutant from the water. Thus we [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Team/Collaborations#Collaboration%20with%20Dundee%20iGEM%20team%202013 | + | Beside the enzymatic degradation of pollutants we found different methods to bind them on our moss filter. We called this system [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Project/Bioaccumulation BioAccumulation]. The most obvious idea was to use binding proteins which were developed for human therapy, such as antibodies, for example. To investigate this idea we used an alternative binding protein, the Anticalin, which was engineered to bind fluorescein as it has a very high affinity, a small size and a robust fold [[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16307475 Vopel et al., 2005]]. Beside this engineered binding protein, we also recognized the idea of [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Team/Collaborations#Collaboration%20with%20Dundee%20iGEM%20team%202013 Dundee iGEM 2013] which sounded quite interesting. This team used a protein which is found in the toxicity mechanism of microcysteins. Dundee wanted to use it as a binding partner to absorb the pollutant from the water. Thus we contacted Dundee iGEM, discussed our idea for a [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Team/Collaborations#Collaboration%20with%20Dundee%20iGEM%20team%202013 collaboration] with them, got their BioBrick, converted it to RFC[25], assembled it into our modular receptor and finally transformed and selected stable transfected moss lines which we finally characterized. Basically the limitation of BioAccumulation applications is that binding proteins are only able to bind one pollutant per binding protein. Due to that fact an extremely high number of binding proteins is required to achieve a recognizable reduction of environmental pollutants. We transformed and selected transgenic moss lines with all three effector proteins and checked the cellular localization of these proteins using fluorescence microscopy. We were able to [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/GM-Moss#The_PhyscoFilter_for_Fluorescein confirm the activity] of Moss lines, containing receptor bound Anticalins, which are able to bind fluorescein, whereas moss lines with a receptor, carrying the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) from our collaboration partner Dundee showed the [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/GM-Moss#The_PhyscoFilter_for_Microcystin localization of our Gene-construct in cytosolic vesicles] and not on the membrane, as expected. This observation is in good agreement with the results presented by Dundee, that the SEC-pathway secretion is not working for this BioBrick. This observation may be explained due to surface exposed cystein residues which tend to aggregate in the oxidizing milieu. Therefore it would be necessary to perform protein engineering to exchange these cystein residues for other amino acid residues in order to increase the stability of this protein. |

==Kill-Switch== | ==Kill-Switch== | ||

| - | Safety is one of the most important issues in synthetic biology. Therefore we implemented a kill switch into our project. For us, it was important to use a trigger, which is ubiquitously present in the environment and absolutely autonomous. We therefore developed a light-triggered kill switch. With this system, the transgenic moss could be cultivated under blue filter foil. As long as the moss grows under this blue foil no red light can be absorbed by the moss, so it stays alive. As soon as the moss escapes from this protected environment the red light is present and the kill switch | + | Safety is one of the most important issues in synthetic biology. Therefore we implemented a kill switch into our project. For us, it was important to use a trigger, which is ubiquitously present in the environment and absolutely autonomous. We therefore developed a [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Project/Killswitch light-triggered kill switch]. With this system, the transgenic moss could be cultivated under blue filter foil. As long as the moss grows under this blue foil no red light can be absorbed by the moss, so it stays alive. As soon as the moss escapes from this protected environment the red light is present and the kill switch is activated. The system was modularized into a sensor module and a suicide module. The sensor domain consists of a split TEV protease which is attached to either the proteins PhyB or PIF. These two proteins dimerize when red light is present and therefore lead to the dimerization of both split TEV subunits, so the reconstitution of the TEV protease is initiated. The suicide module consists of a nuclease which is anchored to the intracellular membrane by a linker which contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a TEV cleavage site. As soon as the sensor module is reconstituted by red light, the TEV protease cleaves the cleavage site at the membrane localized nuclease. Thereby the nuclease is liberated, is transported to the nucleus due to the nuclear localization signal and, in the end, fragments the genome. The choice to use a nuclease instead of siRNA was for example driven by our [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Modeling/Kill_Switch modeling approach] in which we found the siRNA suicide module to be less effective as there is a negative feedback loop which impedes the efficient killing of moss cells. |

| - | We have transformed moss cells with this kill switch and have protected the resulting growing cells, as mentioned before, by blue. | + | We have transformed moss cells with this kill switch and have protected the resulting growing cells, as mentioned before, by blue foil. However when we opened the blue foil after the selection process, all moss cells were dead. This can be explained by a drastically reduced transformation efficiency as the kill switch DNA was >10 kDa or by the fact that the kill switch is reliably killing the cells even without a trigger. In order to test the sensor module in vitro, we have produced the two fusion proteins in vitro as recombinant proteins and have attempted to purify them, which was not successful as the proteins are probably not stable in vitro. Although we only had a single shot to test our kill switch in ''Physcomitrella patens'', we have discussed this system far more than the other parts of our project that worked very well in first experiments. During these discussions on our kill switch we learnt a lot about this system and we described these findings in order to help subsequent iGEM teams who aim to design a reliable and safe kill switch. |

==Implementation== | ==Implementation== | ||

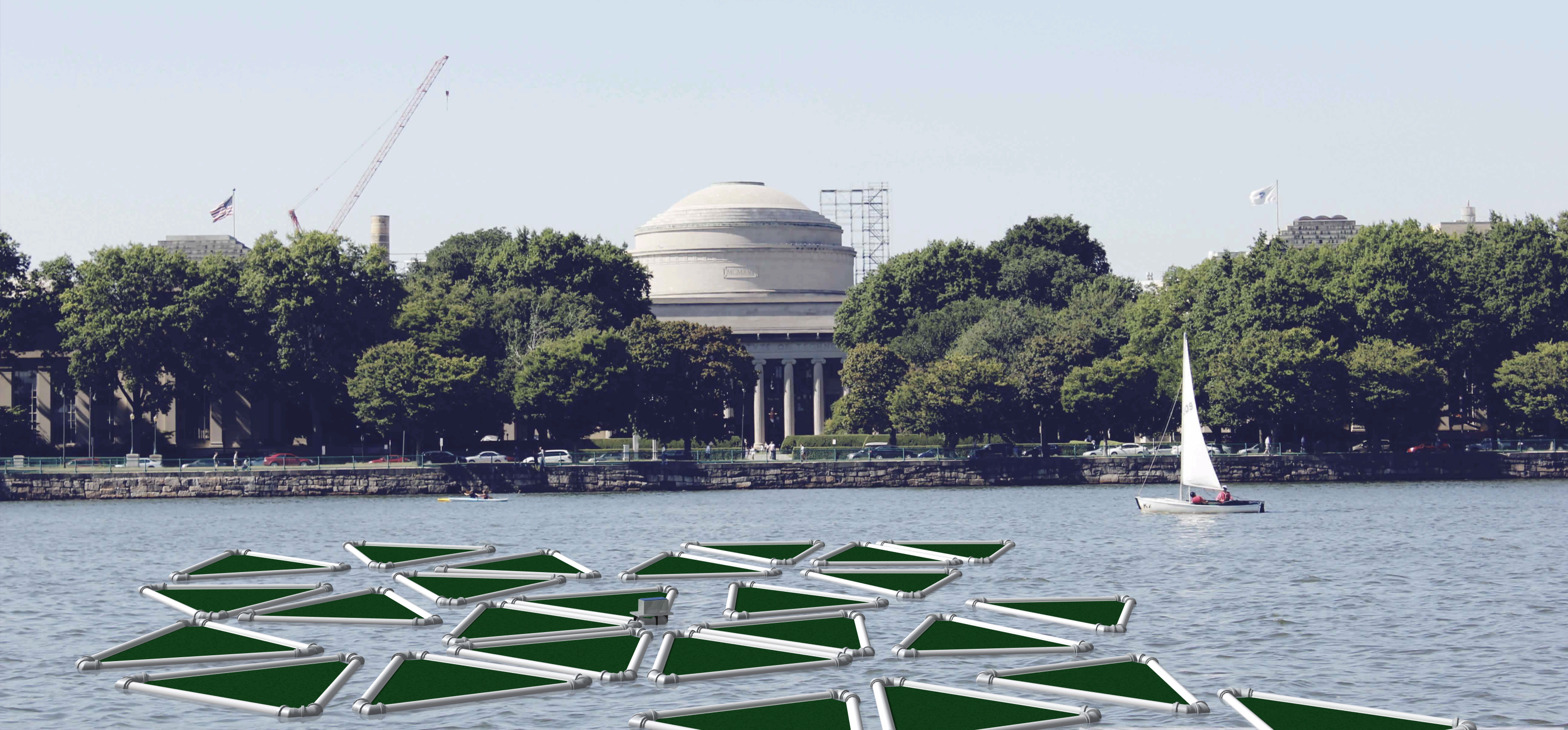

[[File:TUM13_RenderingMIT.jpg|aft.png|thumb|right|400px|'''Figure 3''': Remediation rafts in front of the MIT]] | [[File:TUM13_RenderingMIT.jpg|aft.png|thumb|right|400px|'''Figure 3''': Remediation rafts in front of the MIT]] | ||

| - | Projects in iGEM must not stop at the lab door and therefore it is immensely important to think about technical solutions to implement the transgenic organisms in order to show highest efficacy and safety. For this reason we convinced experts like Prof. Dr. Posten to join our [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/HumanPractice/Interviews#Expert_Counsel:_An_overview advisory board] and have evaluated different cultivation methods for moss such as closed tube reactors, open pond reactors and floating remediation rafts. We came to the conclusion that in the case of immobilized effector proteins an open pond or closed tube reactor will be the superior technology as the degradation requires a large area of contact between the moss and | + | Projects in iGEM must not stop at the lab door and therefore it is immensely important to think about technical solutions to implement the transgenic organisms in order to show highest efficacy and safety. For this reason we convinced experts like Prof. Dr. Posten to join our [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/HumanPractice/Interviews#Expert_Counsel:_An_overview advisory board] and have evaluated [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/Implementation different cultivation methods] for moss such as closed tube reactors, open pond reactors and floating remediation rafts. We came to the conclusion that in the case of immobilized effector proteins an open pond or closed tube reactor will be the superior technology as the degradation requires a large area of contact between the moss and the pollutant to be degraded. As a second possibility we evaluated the secretion of effector proteins such as the laccase, which would then be implemented best on floating [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/Implementation#Our_swimming_remediation_raft remediation rafts] which are cheap to produce, mobile and could also be applied in third world countries with highly contaminated waters. PhyscoFilter moss could be grown on these rafts and would secrete recombinant protein into the water to degrade pollutants in the environment. For all these cultivation methods we built model reactors, tried the cultivation of moss within them and tested the flow characteristics of the systems. For the triangular remediation raft we constructed a life-size prototype which costed only US$ 50. Additionally we developed a measurement device based on an [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Results/How_To#Setting_up_a_basic_Arduino_measuring_device Arduino microcontroller] which measures environmental parameters, sends the data via WiFi to a webserver from where the actual data can be monitored with any smart phone or computer at any place in the world. To get an idea how such remediation rafts could look like on our rivers, we [https://2013.igem.org/Team:TU-Munich/Team/Collaborations#Collaboration_with_Op.N talked to architects] and also rendered an 3D-CAD-model in front of the MIT (see figure 3). |

==Supporting the iGEM Community== | ==Supporting the iGEM Community== | ||

Latest revision as of 03:57, 29 October 2013

Our Project for this summer: Remediation.

During this summer we wanted to work on an iGEM project, which has the potential to become a real world application, since we believe that it is an important step for Synthetic Biology to provide alternative solutions for global problems. For this reason we focused on Bioremediation: The use of organisms to remove emissions caused by humans and to bring the environment back to its natural state. As water is a resource which is absolutely essential for all living organisms, we decided to focus on the pollution of aquatic ecosystems.

Choice of the appropriate chassis for a water filter

Remediation is not new to iGEM, in fact it is a topic the iGEM community has worked on for nearly 10 years now. Therefore a set of promising BioBricks was already available in the Parts Registry, which we wanted to use in order to increase the knowledge on these effector proteins. Having found suitable effector proteins, we discussed about the most suitable chassis for our application. Most of the previous projects on Bioremediation were based on E. coli, whereas we decided to use a plant instead. Photosynthesis carried out by the plants will allow the water filter to maintain and renew itself without the addition of any nutrients. We considered algae such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Bryophytes such as Physcomitrella patens and higher plants like Arabidopsis thaliana. In the end Physcomitrella patens was the chassis of choice as it already grows in a filter-like structure and can be cultivated in terrestric as well as in aquatic conditions. Additionally it is a well established organism in biotechnology. Working with Physcomitrella patens is not easy considering the 1-2 months it takes from the transformation process to the experiments with stable transfected plants and the doubling times of 3-6 days. As nobody at the TU Munich works with the moss Physcomitrella patens, we looked for an expert and found Prof. Reski who occupies a professorship at Freiburg University. We were very happy to gain him as an advisor during our project. For the use of Physcomitrella patens in iGEM we created a strong constitutive promoter ([http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1159306 BBa_K1159306]), a plant terminator ([http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1159307 BBa_K1159307]) and an antibiotic selection marker ([http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1159308 BBa_K1159308]), which were all used to transform and select 21 different transgenic moss lines.

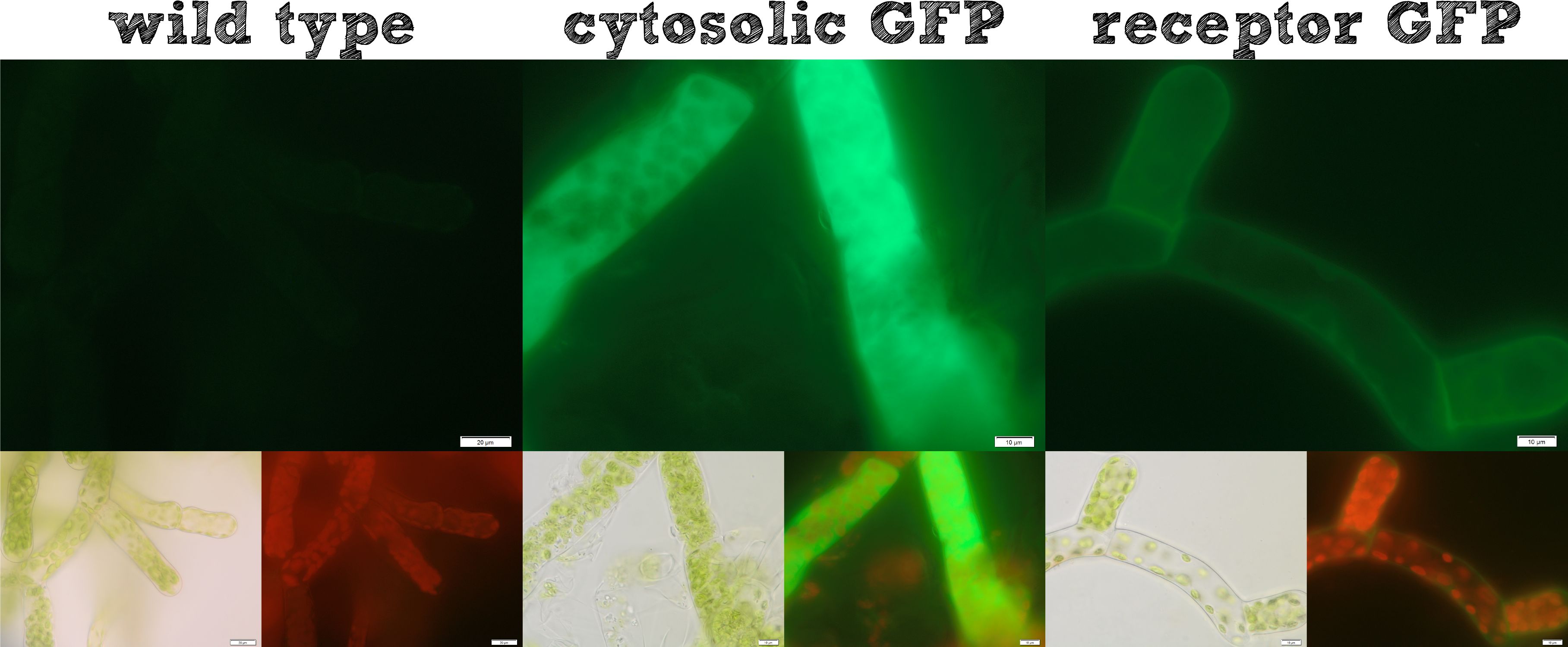

Localization of effector proteins

The actual remediation of pollutants is accomplished by effector proteins which function with significantly different mechanisms. Thus it was important to enable the localization of effector proteins at different cellular sites. Cytosolic effector proteins are easily expressed, whereas for secretion a signal peptide BioBrick is cloned ahead of the effector protein. Several receptor signal peptides from Physcomitrella patens and other organisms were analyzed by using bioinformatics tools. The signal peptide of the Somatic Embryogenesis Receptor-like Kinase (SERK) from Physcomitrella patens and the IgK signal peptide from Mus musculus, which is described in literature to function in Physcomitrella, were chosen. The secretion of a newly introduced luciferase with both of these signal peptides was investigated for 8 clones each. No detectable secretion for the IgKappa, but a high secretion rate for the SERK signal peptide was shown. Successful secretion could be achieved using the SERK signal peptide. Because the secreted effector proteins are not attached to the moss cell, they diffuse into the water, which could be suboptimal, for example if you want to remove pollutants by simply binding them. Therefore we designed a modular receptor for Physcomitrella, which can carry effector proteins at the outer side of the cell membrane. For this purpose bioinformatics methods were used again and the SERK transmembrane domain was chosen to be the best one. A receptor composed of (1) the SERK signal peptide, (2) an extracellularly located effector protein, (3) a linker with a Strep-tag II and a TEV protease cleavage site, (4) the SERK transmembrane domain, (5) a short linker domain and (6) a green fluorescent protein were assembled using the RFC[25] standard. This highly modular receptor was successfully transformed into Physcomitrella patens and stable cell lines were selected. These stable cell lines were used for experiments. The localization of the membrane-bound GFP could be detected clearly on the surface of the moss cells (see figure 1), whereas cells expressing GFP cytosolically in the moss, showed a uniform fluorescence all over. Further we incubated the moss cells with recombinant TEV protease, which diffused through the cell wall, cleaved the TEV site within the extracellular domain of the receptor and liberated the NanoLuc luciferase. The luciferase assay of the supernatant at the beginning of this incubation and after 16 hours showed a dramatic increase in luminescence, which is further evidence that our modular receptor is located in the membrane and - even better - in the right orientation, exposed to the extracellular space. Beyond the possibility to locate an effector protein in the extracellular space, we thought about further applications and found the SypCatcher-SpyTag System to be a perfect tool for our needs http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22366317 Zakeri et al., 2012. In this system a peptide bond is formed between the side chains of two protein domains in an efficient manner. With this system it is not necessary to fuse effector proteins to a specific terminus of the receptor any more, it even becomes possible to immobilize effector proteins which are only active as multimeric proteins and it would also be feasible to express a single receptor carrying a SpyCatcher domain at the outer side of the membrane which subsequently binds a set of different effector proteins which are secreted and are immobilized afterwards. Constructs were created with a His-tagged SypCatcher, a SypTag with an N-terminal or C-terminal SpyTag or with protein domains on both termini of the SpyTag. These constructs were produced recombinantly in E. coli. Afterwards the proteins were purified. Protein coupling experiments were performed and the formation of isopeptide bonds was confirmed by pull-down experiments and reducing SDS-PAGE. Summarizing these results, all our intended localizations in Physcomitrella patens worked, empowering the iGEM community to work creatively with Phycomitrella patens as a new chassis.

BioDegradation

Under the headline BioDegradation we investigated effector proteins which degrade pollutants by enzymatic catalysis. For this purpose we introduced the new BioBrick Erythromycin Esterase (EreB) which degrades macrolide antibiotics. Additionally we used well established BioBricks for BioDegradation. We improved the Laccase from Bacillus pumilus, established by the iGEM Team of Bielefeld in 2012, by converting it to RFC[25] in order to be able to fuse it to the extracellular domain of our receptor. Both enzymes were produced as recombinant proteins and purified. Enzymatic characterization was carried out concerning salt tolerance, substrate and pH dependence. For the laccase temperature dependence and the half-life in river water was additionally estimated. All data was fitted in our enzyme kinetic modeling. The aim was to analyze this data and to provide a solid base for our filter calculator. This calculator uses all the data produced in our enzyme characterization to extrapolate from them for the large scale implementation of transgenic PhyscoFilters in waste water treatment plants or on rivers. We assumed the secretory production of laccase by our moss as the laccase degrades a wide variety of important pollutants such as the pain killer diclofenac, the oral contraceptive ethinylestradiol or iodined x-ray contrast media. All these substances are present in nature and are hardly degradable by conventional methods. While using this calculator for modeling, we learned that factors such as the degree of pollution in rivers, the average temperature in a specific country, the enzyme half-life time, as well as the actual amount of secreted protein play an important role for the efficacy of our PhyscoFilter. Generally the results show that approximately an area of 20 football fields would be required to produce enough laccase to reduce the contamination of the large river Rhein with the mentioned pharmaceutical compounds, while half a field would suffice for a large waste water treatment plant. Beside this result we also produced several different stable transgenic moss lines for our BioDegradation module and were able to show that our cytoplasmically expressed Erythromycin Esterase B enables our moss to successfully degrade the macrolide antibiotic Erythromycin. This experiment was analyzed by using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS). It worked for the recombinant protein as well as for the transgenic plant giving the proof of principle for Physcomitrella patens as a bioremediation organism.

BioAccumulation

Beside the enzymatic degradation of pollutants we found different methods to bind them on our moss filter. We called this system BioAccumulation. The most obvious idea was to use binding proteins which were developed for human therapy, such as antibodies, for example. To investigate this idea we used an alternative binding protein, the Anticalin, which was engineered to bind fluorescein as it has a very high affinity, a small size and a robust fold http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16307475 Vopel et al., 2005. Beside this engineered binding protein, we also recognized the idea of Dundee iGEM 2013 which sounded quite interesting. This team used a protein which is found in the toxicity mechanism of microcysteins. Dundee wanted to use it as a binding partner to absorb the pollutant from the water. Thus we contacted Dundee iGEM, discussed our idea for a collaboration with them, got their BioBrick, converted it to RFC[25], assembled it into our modular receptor and finally transformed and selected stable transfected moss lines which we finally characterized. Basically the limitation of BioAccumulation applications is that binding proteins are only able to bind one pollutant per binding protein. Due to that fact an extremely high number of binding proteins is required to achieve a recognizable reduction of environmental pollutants. We transformed and selected transgenic moss lines with all three effector proteins and checked the cellular localization of these proteins using fluorescence microscopy. We were able to confirm the activity of Moss lines, containing receptor bound Anticalins, which are able to bind fluorescein, whereas moss lines with a receptor, carrying the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) from our collaboration partner Dundee showed the localization of our Gene-construct in cytosolic vesicles and not on the membrane, as expected. This observation is in good agreement with the results presented by Dundee, that the SEC-pathway secretion is not working for this BioBrick. This observation may be explained due to surface exposed cystein residues which tend to aggregate in the oxidizing milieu. Therefore it would be necessary to perform protein engineering to exchange these cystein residues for other amino acid residues in order to increase the stability of this protein.

Kill-Switch

Safety is one of the most important issues in synthetic biology. Therefore we implemented a kill switch into our project. For us, it was important to use a trigger, which is ubiquitously present in the environment and absolutely autonomous. We therefore developed a light-triggered kill switch. With this system, the transgenic moss could be cultivated under blue filter foil. As long as the moss grows under this blue foil no red light can be absorbed by the moss, so it stays alive. As soon as the moss escapes from this protected environment the red light is present and the kill switch is activated. The system was modularized into a sensor module and a suicide module. The sensor domain consists of a split TEV protease which is attached to either the proteins PhyB or PIF. These two proteins dimerize when red light is present and therefore lead to the dimerization of both split TEV subunits, so the reconstitution of the TEV protease is initiated. The suicide module consists of a nuclease which is anchored to the intracellular membrane by a linker which contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a TEV cleavage site. As soon as the sensor module is reconstituted by red light, the TEV protease cleaves the cleavage site at the membrane localized nuclease. Thereby the nuclease is liberated, is transported to the nucleus due to the nuclear localization signal and, in the end, fragments the genome. The choice to use a nuclease instead of siRNA was for example driven by our modeling approach in which we found the siRNA suicide module to be less effective as there is a negative feedback loop which impedes the efficient killing of moss cells. We have transformed moss cells with this kill switch and have protected the resulting growing cells, as mentioned before, by blue foil. However when we opened the blue foil after the selection process, all moss cells were dead. This can be explained by a drastically reduced transformation efficiency as the kill switch DNA was >10 kDa or by the fact that the kill switch is reliably killing the cells even without a trigger. In order to test the sensor module in vitro, we have produced the two fusion proteins in vitro as recombinant proteins and have attempted to purify them, which was not successful as the proteins are probably not stable in vitro. Although we only had a single shot to test our kill switch in Physcomitrella patens, we have discussed this system far more than the other parts of our project that worked very well in first experiments. During these discussions on our kill switch we learnt a lot about this system and we described these findings in order to help subsequent iGEM teams who aim to design a reliable and safe kill switch.

Implementation

Projects in iGEM must not stop at the lab door and therefore it is immensely important to think about technical solutions to implement the transgenic organisms in order to show highest efficacy and safety. For this reason we convinced experts like Prof. Dr. Posten to join our advisory board and have evaluated different cultivation methods for moss such as closed tube reactors, open pond reactors and floating remediation rafts. We came to the conclusion that in the case of immobilized effector proteins an open pond or closed tube reactor will be the superior technology as the degradation requires a large area of contact between the moss and the pollutant to be degraded. As a second possibility we evaluated the secretion of effector proteins such as the laccase, which would then be implemented best on floating remediation rafts which are cheap to produce, mobile and could also be applied in third world countries with highly contaminated waters. PhyscoFilter moss could be grown on these rafts and would secrete recombinant protein into the water to degrade pollutants in the environment. For all these cultivation methods we built model reactors, tried the cultivation of moss within them and tested the flow characteristics of the systems. For the triangular remediation raft we constructed a life-size prototype which costed only US$ 50. Additionally we developed a measurement device based on an Arduino microcontroller which measures environmental parameters, sends the data via WiFi to a webserver from where the actual data can be monitored with any smart phone or computer at any place in the world. To get an idea how such remediation rafts could look like on our rivers, we talked to architects and also rendered an 3D-CAD-model in front of the MIT (see figure 3).

Supporting the iGEM Community

It is really amazing to see how the iGEM community advanced over the last years. We can proudly say that we invested efforts to take the iGEM community to another level. We created a software tool which translates protein coding BioBricks in the registry to amino acid sequences, calculates various parameters and compiles alignments with data from various data banks. In the end all collected information for a BioBrick is exported into a standardized table which can easily be integrated into the part descriptions of BioBricks. We submitted a RFC for the AutoAnnotator which obtained the number RFC[96]. Besides this software toll we have written tutorials on wiki programming, creating animated gifs of protein structures and the usage of Arduino microcontrollers for future iGEM projects.

References:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19021876 Gitzinger et al., 2009 Functional cross-kingdom conservation of mammalian and moss (Physcomitrella patens) transcription, translation and secretion machineries, Plant Biotechnol J. 2009 Jan;7(1):73-86

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16307475 Vopel et al., 2005 Vopel S, Mühlbach H, Skerra A. (2005) Rational engineering of a fluorescein-binding anticalin for improved ligand affinity. Biol. Chem., 386(11):1097-104.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22366317 Zakeri et al., 2012 Zakeri B, Fierer JO, Celik E, Chittock EC, Schwarz-Linek U, Moy VT, Howarth M. (2012). Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 20;109(12)

"

"

AutoAnnotator:

Follow us:

Address:

iGEM Team TU-Munich

Emil-Erlenmeyer-Forum 5

85354 Freising, Germany

Email: igem@wzw.tum.de

Phone: +49 8161 71-4351