Team:TU-Munich/Project/Physcomitrella

From 2013.igem.org

LouiseFunke (Talk | contribs) (→As a new chassis for iGEM) |

LouiseFunke (Talk | contribs) (→BioBricks for Proteinexpression in Physcomitrella) |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

==BioBricks for Proteinexpression in ''Physcomitrella''== | ==BioBricks for Proteinexpression in ''Physcomitrella''== | ||

| - | <div class="box- | + | <div class="box-left">Text</div> |

| - | < | + | <div class="box-right">Text</div> |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Revision as of 22:16, 15 September 2013

Physcomitrella - A new chassis for iGEM

General description

The moss Physcomitrella patens belongs to the land plant division Bryophyta, which are one of the earliest representatives of the land plants (Embryophyta) having evolved from green algae about 470 million years ago during the early Paleozoic. Hence mosses have a much simpler anatomy than higher land plants such as trees and flowering plants, which in particular means that they have not yet developed a vascular system, i.e an internal transport system for water and nutrients. Since they also lack a complex waterproofing system to prevent absorbed water from evaporating they need a moist environment to grow. Their main habitats are therefore shady and damp places such as woods and edges of streams but they are also found to be resistant to periods of drought and therefore can be found widely spread around the world, from the tropics to tundra regions, from coastal sand dunes up to high mountains.

The general organization of plant tissue into roots, stem and leaves is found in a much more basic version in mosses. They show a differentiated stem with simple leaves, usually only a single layer of cells thick and lacking veins, that are used to absorb water and nutrients. Instead of roots they have similar threadlike rhizoids http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/Reski_1998_BotActa-111_1_scan.pdf Reski, 1998. These have a primary function as mechanical attachment rather than extraction of soil nutrients. Due to not having a vascular system bryophytes are doomed to stay small throughout their life-cycle typically stretching about 1-10 cm.

However different mosses and vascular plants are because of the early diverge of the evolutionary lineages, they share fundamental genetic and physiological processes. Hence a good approach to studying the complexity of higher land plants is to look at the bryophytes with their much simpler phenotype. Here researchers chose Physcomitrella patens as a model organism with a genome size of about 450 Mb along 27 chromosomes that is highly similar to other land plants in both exon-intron-structure and codon usage. http://www.plantphysiol.org/content/127/4/1430 Schaefer and Zryd, 2001

Life cycle

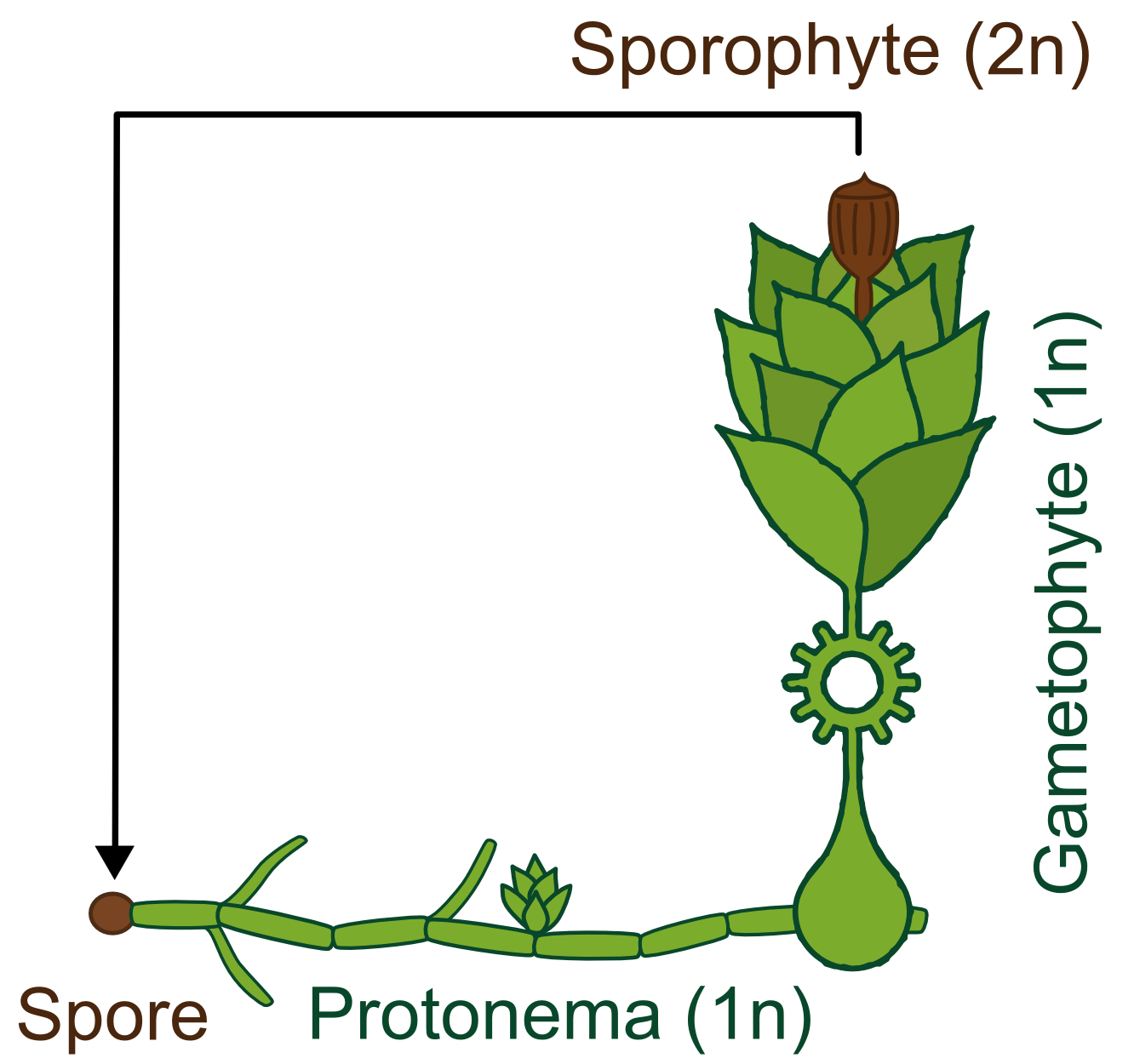

Generally land plants show an alternation of generations, the haploid (1n) gametophyte produces sperm and eggs which fuse and transform into the diploid (2n) sporophyte. This then forms haploid spores which become new gametophytes. Besides having no vascular system, bryophytes also differ from higher land plants in the fact that the gametophyte is the dominant phase of their life cycle, whereas in vascular plants the principal generation is the sporophyte.

The life cycle of P. patens http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/Reski_1998_BotActa-111_1_scan.pdf Reski, 1998 only takes about 3 months and starts with the spore developing into a filamentous structure, the juvenile, transitory stage of the gametophyte, called protonema, which is composed of two types of cells. The chloronema cells with large and numerous chloroplasts mostly perform photosynthesis and thus supply the photoautotrophic plant with energy while the task of the caulonema cells is fast growth. The adult stage of the gametophyte, called gametophore ("gamete-bearer") has a more complex structure bearing leafs, stem and rhizoids. The transition from juvenile to adult gametophyte is started by initial cells in the protonema filament that differentiate into buds. The budding is therefore a single-cell-event, greatly stimulated by the plant hormone cytokinin, which promotes cell division.

The sex organs of the moss develop from the tip of the gametophore. P. patens is monoicous, meaning that male and female organs are produced in one plant. When liquid water is surrounding the tip, flagellate sperm cells can swim from the male sex organ to the female organ and fertilize the egg within. A zygote then develops into the sporophyte, which in turn produces thousands of haploid spores by meiosis. Sporophytes are typically physically attached to and dependent on supply from the dominating gametophyte.

Advantages of Physcomitrella as a model organism

General

- P. patens stands out among the whole plant kingdom as the sole exception where gene targeting is feasible as an easy and fast routine procedure, even with an efficiency similar to S. cerevisiae, due to highly efficient homologous recombination. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14586556 Reski et al., 2004 For that reason it is very easy to create knockout mosses by precise mutagenesis following the approach of reverse genetics in order to study the function of genes. Performing functional genomics in higher organisms is very important to understand biological functions of proteins in a multicellular context, e.g. in the context of cell-cell-contacts.

- As mosses mainly are in a haploid stage during their life cycle they are very straight-forward objects for genetics because complex backcrosses to determine changes in the genotype are not necessary

- Moss development starts with a filamentous tissue, the protonema, which is growing by apical cell division and, therefore is perfectly suitable for cell-lineage analysis since development of the plant can be pinpointed to the differentiation of a single cell. http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/Reski_1998_BotActa-111_1_scan.pdf Reski, 1998 Also the simple life cycle makes P. patens a very useful item for developmental biology

- P. patens is increasingly used in biotechnology as a study object with implications for crop improvement or human health. Moss bioreactors can be used as an alternative to animal cell cultures (e.g. CHO cells) for the easy, inexpensive and safe production of complex biopharmaceuticals http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0958166907000948 Reski and Decker, 2007 . For example it is a successful tool to produce asialo-EPO, a specific variant of Erythropoetin, which can perform its protective role by inhibiting apoptosis but has lost the potential doping activity. This safe drug is hard to produce in animal cell culture but easy to produce in the moss without impacting its growth or general performance http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22621344 Decker et al., 2012.

- (plant evolution by comparing with results from higher plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana)

Expertbox: Prof. Reski

As a new chassis for iGEM

- As a plant P. patens offers interesting opportunities for application as it is self sustaining, renewable and a natural part of our environment. Therefore it is much easier to implement it into real world scenarios than bacteria or yeast. And although there is the disadvantage of having to wait about two weeks after transformation until experiments can be done, this is still very short considering the high complexity of the organism and can easily be done in the timeframe of the competition, by preparing the DNA constructs in bacteria.

- P. patens is a well studied model organism which means that besides having its full genome sequenced in 2006 there are well equipped [http://www.cosmoss.org databases]. Furthermore there exists an [http://www.moss-stock-center.org International Moss Stock Center (IMSC)] in which many ecotypes, mutants and transgenics of P. patens are stored and freely accessible to the scientific community. So there is enough knowledge and material to work on for synthetic biologists.

- At the same time the moss offers access to very exciting new physiological processes since it is a much more complex multicellular eukaryotic organism than yeast.

- P. patens is an easy plant to work with and requires neither expensive maintenance facilities nor large laboratory space. Most of the basic tools for high precision mutagenesis have been tested on this plant, were found to work, and are easily available (see Moss methods below).

Experiment-Box: Toxicitydetermination

Moss methods - working with Physcomitrella

The techniques used for the cultivation and manipulation of Physcomitrella patens are based on the knowledge of the chair for Plantbiotechnology of Prof. Dr. Reski at Freiburg University, which are available at [http://www.plant-biotech.net Plant-Biotech.net].

- Cell culture: Physcomitrella patens plants can be cultivated either on solidified medium or in liquid medium. Liquid cultures can be kept in Erlenmeyer flasks under constant rotation and light exposure or in bioreactors for large scale production. By regularly (ideally weekly) disrupting the plants mechanically with an Ultra-Turrax a homogenized culture can be achieved.

- Storage: Long-term storage of Physcomitrella strains can be achieved by cryo-preservation. This procedure ensures a maximum survival rate of the plant by preconditioning and controlled freezing. http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/PlantBiol_2004_Schulte_pageproof.pdf Schulte and Reski, 2004

- Targeted knockout: P. patens is unique among plants in its high efficiency of gene targeting by homologous recombination. To knockout a specific gene a gene disruption construct has to be generated. This consists of the gene to be silenced with a selection cassette (usually the nptII gene) inserted into its center by suitable restriction sites. The moss is then transformed with this DNA construct which is integrated into the genome by homologous recombination. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14586556 Reski et al., 2004

- Transformation: Transformation of P. patens requires protoplasts of the plant, which can be obtained by cell wall digesting enzymes. The protoplasts can either be transformed by particle bombardment or via polyethylene glycol (PEG), which is the easiest and most commonly used method. The DNA constructs should be linearized for optimal transformation and contain a selection marker for subsequent screening. After transformation the protoplasts are cultivated in the dark for 12-16 h followed by 10 days under normal growth conditions during which they regenerate their cell wall. Afterwards they are plated onto solidified medium in normal petri dishes and first experiments can be executed. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00260654 Schaefer et al., 1991

- Analysis of transformants: First of all the transformed protoplasts are plated on solidified medium containing the antibiotic G418 (Geneticin) to which successfully transformed plants should be resistant due to the selection marker nptII which encodes the enzyme neomycin phosphotransferase. Secondly the transformants are analyzed by a PCR screen using primers that are derived from sequences of the selection marker cassette http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/PlantMolecularBiologyReporter_2002_Schween.pdf Schween et al., 2002.

This is only a summary of the most important techniques in working with P. patens. For a full description of these methods please see our methods page.

BioBricks for Proteinexpression in Physcomitrella

Localization of transgenic effector proteins

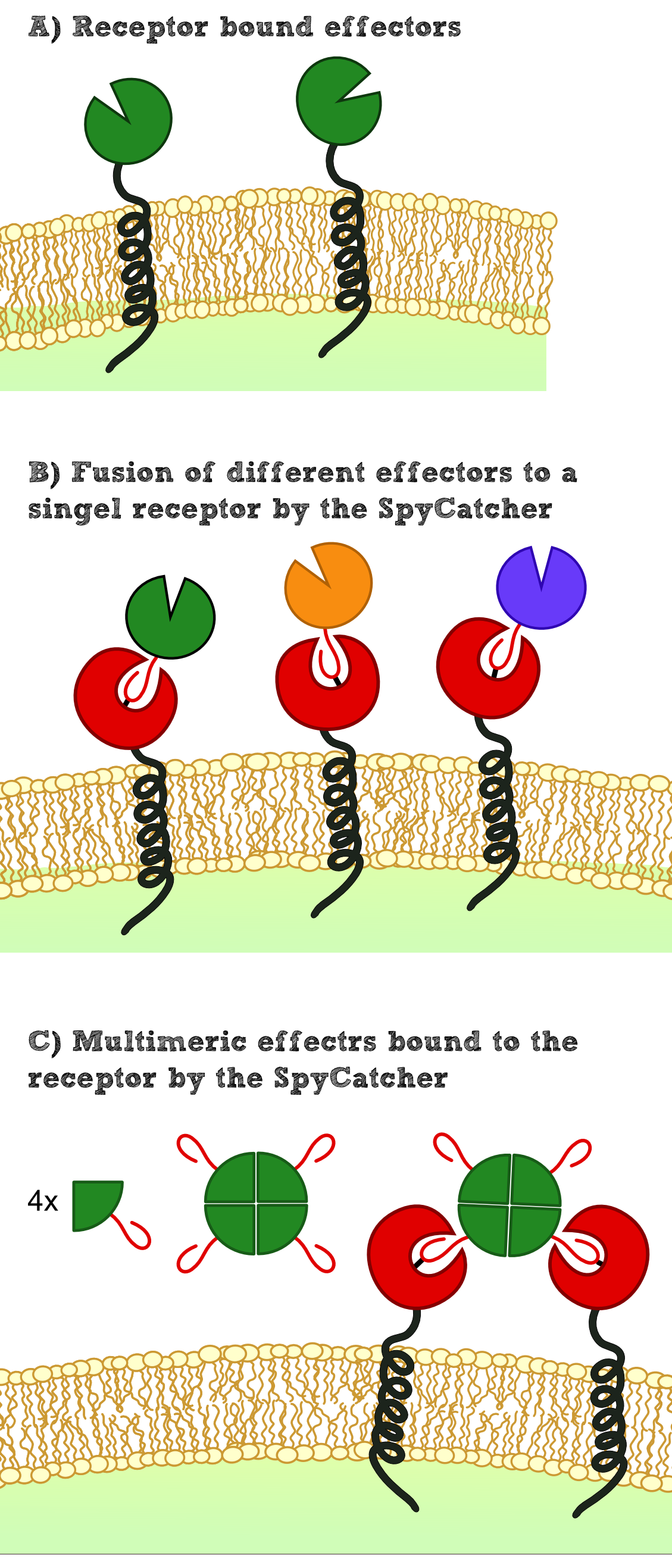

In order to use Physcomitrella as a chassis for Phytoremediaton it is essential to be able to express effector proteins in different compatiments. This includes at first a cytoplasmatic expression of cytosolic effectors which degrade xenobiotics which are able to cross the cell membrane and which might be dependent on cofactors for the degradation or conjugation to decrease environmental pollution. In a second attempt it is necessary to implement the possibility to secrete effectors outside the cell which are more accessible for the their respective target molecule. Finally it would be desirable to have the possibility to express effectors which are immobilized on the cellular membrane. This woule allow the creation of a system which does not release transgenic proteins in the environment and would allow to internalize substances which were bound by recombinant binding proteins into the cell.

The cytosolic expression of efectorproteins can be achieved by cloning the respective BioBrick behind the Actin_5 promoter which can be in RFC 10 or RFC 25. For the secretion of effectors we added the signal peptide from an antibody [Fussenegger] and also tested the signal peptide from the SERK receptor of Physcomitrella patens which both should be suitable BioBricks to accomplish secretion. For this purpose the signal peptides were created as RFC 25 N-parts and the effectors need to be availible in RFC 25 to create fusion proteins. Finally the inclusion of recombinant effector proteins into a receptor which is functional in Physcomitrella patens was investigated by the construction of a synthetic receptor based on the SERK receptor

SERK: The Blueprint from P. patens for a Synthetic Moss Receptor

Advanced expression: Employing SpyTag & SpyCatcher for difficult cases

At a certain point it will be necessary to think about transgenic moss which is able to degrade several different xenobiotics using different effector molecules. In order to prepare for these posterior needs we decided to integrate the SpyCatcher and SpyTag system into our project [Ref]. This Spy-system allows for the creation of posttranslational protein fusion based on a covalent bond which is formed between the side chains of residues of a SypCatcher and a SpyTag.

Therefore it is possible to create a protein fusion of the SypTag with a recombinant effector protein which is expressed separately (e.g. with anothe expression strength) and becomes in the secretory pathway fused to a receptor which contains the SypCatcher. By these means it becomes possible to express the SERK-receptor under a strong promoter and to adjust the expression of different effector proteins to their particuluar necessity (Fig. x B).

On the other hand enzymatic effectors might be active as multimeric proteins and thus not every subunit can be fused to a receptor for steric reasons. In this case the application of the SpyTag system also seems advantageous as it allows the multimeric protein to assemble into its functional form before it becomes immobilized to the outer side of the cellular membrane by its SpyTags (Fig. x C).

References:

- http://www.plantphysiol.org/content/127/4/1430 Schaefer and Zryd, 2001 Schaefer, D.G. and Zrÿd, J. (2001). The Moss Physcomitrella patens, Now and Then. Plant Physiology, 127(4):1430-1438.

- http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/Reski_1998_BotActa-111_1_scan.pdf Reski, 1998 Reski, R. (1998). Development, Genetics and Molecular Biology of Mosses. Bot. Acta, 111:1-15.

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0958166907000948 Reski and Decker, 2007 Decker, E.L. and Reski, R. (2007). Moss bioreactors producing improved biopharmaceuticals. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 18(5):393-398.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14586556 Reski et al., 2004 Hohe, A., Egener, T., Lucht, J.M., Holtorf, H., Reinhard, C., Schween, G. and Reski, R. (2004). An improved and highly standardised transformation procedure allows efficient production of single and multiple targeted gene-knockouts in a moss, Physcomitrella patens. Curr Genet., 44(6):339-47.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22621344 Reski et al., 2012 Parsons, J., Altmann, F., Arrenberg, C. K., Koprivova, A., Beike, A. K., Stemmer, C., Gorr, G., Reski, R. and Decker, E. L. (2012). Moss-based production of asialo-erythropoietin devoid of Lewis A and other plant-typical carbohydrate determinants. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 10:851–861.

- http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/PlantBiol_2004_Schulte_pageproof.pdf Schulte and Reski, 2004 Schulte, J. and Reski, R. (2004). High throughput Cryopreservation of 140 000 Physcomitrella patens Mutants. Plant Biology, 6:119-127.

- http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00260654 Schaefer et al., 1991 Schaefer, D., Zryd, J.-P., Knight, C., Cove, D. (1991). Stable transformation of the moss Physcomitrella patens. Molecular and General Genetics, 226:418-424.

- http://www.plant-biotech.net/paper/PlantMolecularBiologyReporter_2002_Schween.pdf Schween et al., 2002 Schween, G., Fleig, S., Reski, R. (2002). High-throughput-PCR screen of 15,000 transgenic Physcomitrella plants. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter, 20:43–47.

"

"

AutoAnnotator:

Follow us:

Address:

iGEM Team TU-Munich

Emil-Erlenmeyer-Forum 5

85354 Freising, Germany

Email: igem@wzw.tum.de

Phone: +49 8161 71-4351