Team:British Columbia/Project/Vanillin

From 2013.igem.org

(→Vanillin) |

|||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | 1) <a href="http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/536/art%253A10.1007%252Fs12010-012-0066-1.pdf?auth66=1383179957_b65daa7df179f4f97a13ebc2afab608e&ext=.pdf"> Kaur, B.,and Chakraborty, D. (2013) Biotechnological and Molecular Approaches for Vanillin Production: a Review .</i> <b>169</b>, 1353-1372. </a> | + | 1) <a href="http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/536/art%253A10.1007%252Fs12010-012-0066-1.pdf?auth66=1383179957_b65daa7df179f4f97a13ebc2afab608e&ext=.pdf"> Kaur, B.,and Chakraborty, D. (2013) Biotechnological and Molecular Approaches for Vanillin Production: a Review .<i>Appl Biochem Biotechnol.</i> <b>169</b>, 1353-1372. </a> |

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | 2) <a href="http:// | + | 2) <a href="http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/69/art%253A10.1007%252Fs002530100687.pdf?auth66=1383180180_3192c66d6c287286da533a5399144d84&ext=.pdf"> Priefert, H., Rabenhorst.,and Steinobuchel, A. (2001) Biotechnological production of vanillin. <i>Appl Microbiol Biotechnol.</i> <b>56</b>, 296-314. </a> |

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 00:46, 29 October 2013

iGEM Home

Contents |

Vanillin

Meeting the Demand of World's Most Popular Flavour

Vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzadledhyde) is a valuable industrial aromatic compound involved in flavouring, preservatives, pharmaceuticals, and fragrances (1). Naturally, vanillin is extracted from vanilla pods in flat-leaved Vanilla planifolia, Vanilla tahitiensis, and Vanilla pompona. Commercialization of botanical-derived vanillin, however, is infeasible and cannot achieve the demands of the world vanilla market due to unpredictable harvesting yields, climate fluctuations, and labour-intensive processing. Only 0.2% of world production is derived from of plant-based vanillin extraction while majority of vanillin supply is chemically synthesized. Chemical synthesis of vanillin from petrochemical precursors, such as guaiacol and glyoxylic acid, produce over 10,000 tonnes of vanillin per year. Despite production by chemical synthesis, the demand for vanillin still outcompetes supply (2).

To meet the growing consumption of vanillin by industries while fulfilling the market for more 'natural' or 'healthy' vanillin, the focus has shifted to alternative methods of vanillin production by biosynthesis from more natural precursors, such as lignin, phenolic stilbenes, isoeugenol, eugnol, ferulic acid, and aromatic acids (1,3). Aligned with this movement, European and United States legislations have allowed microbial production of vanillin to be classified as natural vanillin (1,2).

Microbial Synthesis of Vanillin

Vanillin production in microorganisms has been heavily researched in Pseudomonas sp., Amyclatopsis sp., Sphingomonas pauimobilis,Rhodococcus , Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Streptomyces setonii. One important pathway that these microorganisms share for vanillin production is the conversion of ferulic acid to vanillin. Ferulic acid (4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid), or hydroxycinnamic acid, is a component of the cell walls in cereals, woods, and sugar beets. Ferulic acid is best utilized as a precursor for synthesis of aromatic compounds such as vanillin, which involves 2 enzymes: the conversion of ferulic acid to feruloyl-CoA by feruloyl-CoA synthetase (Fcs) enzymes and the conversion of feruloyl-CoA into vanillin by enoyl-CoA hydratase/aldolase (Ech) enzymes (1,2).

Our goal is to produce vanillin in E.coli by heterologously expressing these 2 genes (fcs and ech)from Psuedomonas putida KT2440 and feeding in ferulic acid as a substrate (4). Furthermore, we intend to recreate the biosynthetic pathway by KULeuven iGEM 2009 to produce vanillin starting from aromatic amino acids such as tyrosine.

Chemistry

Data

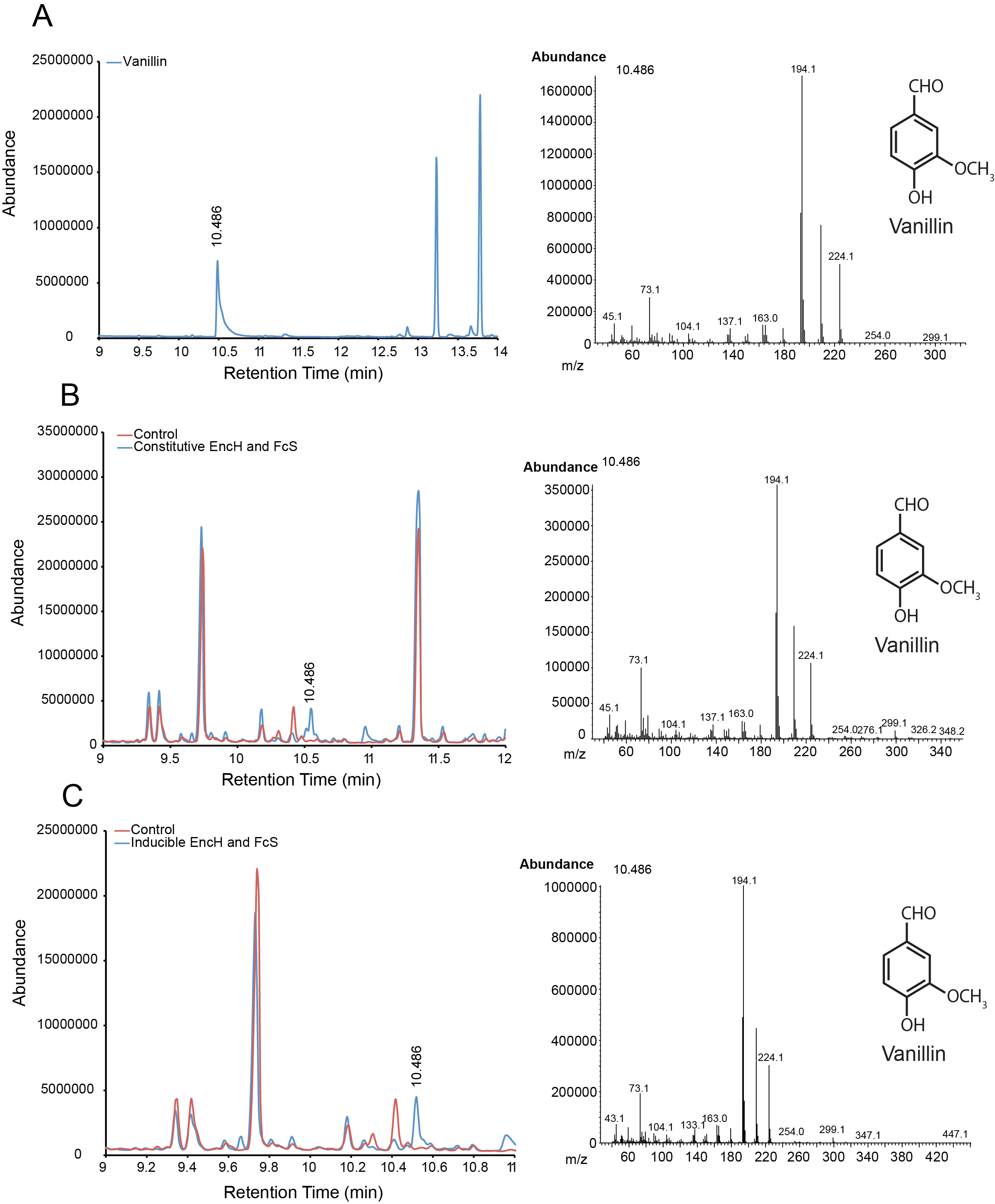

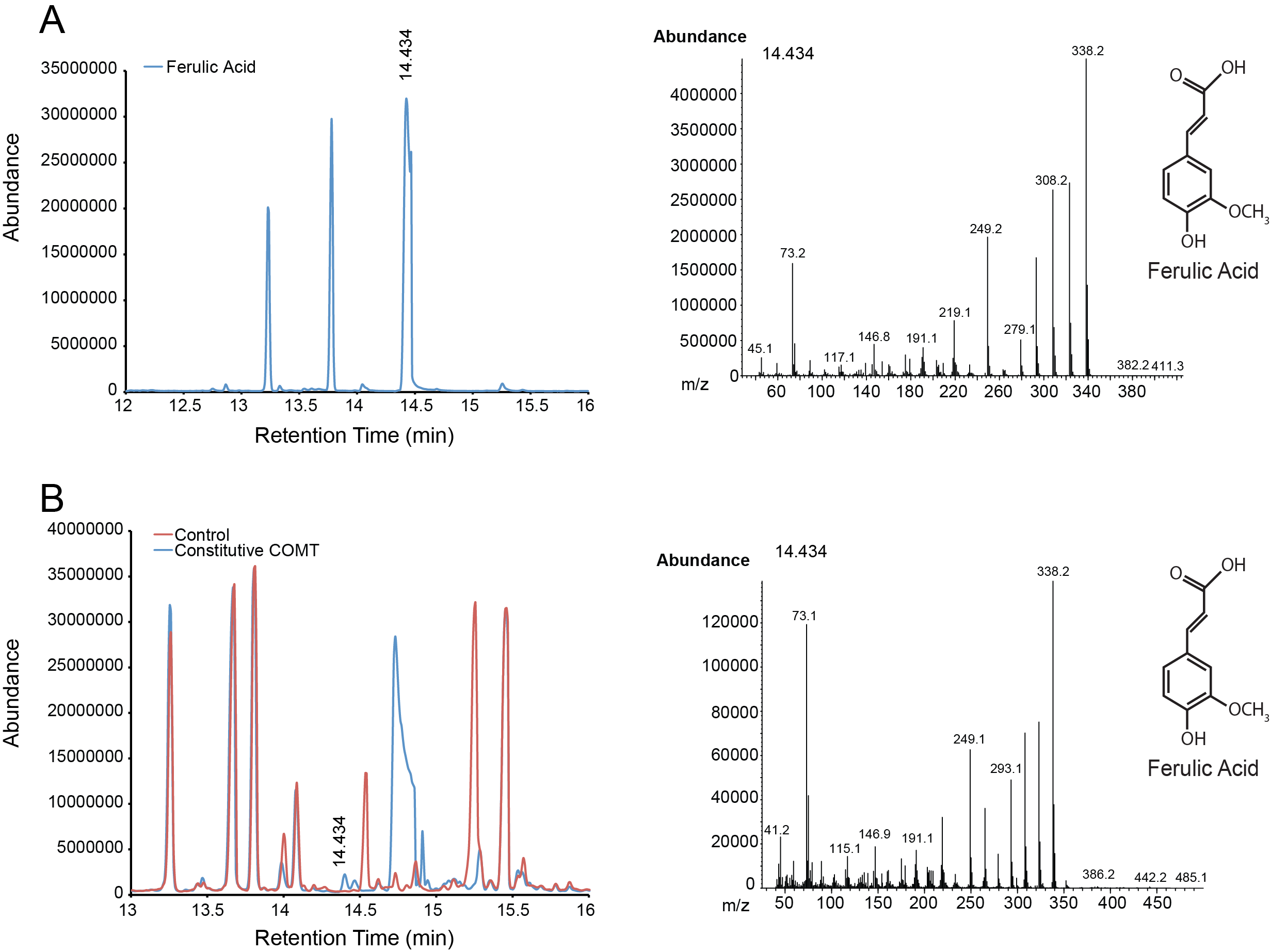

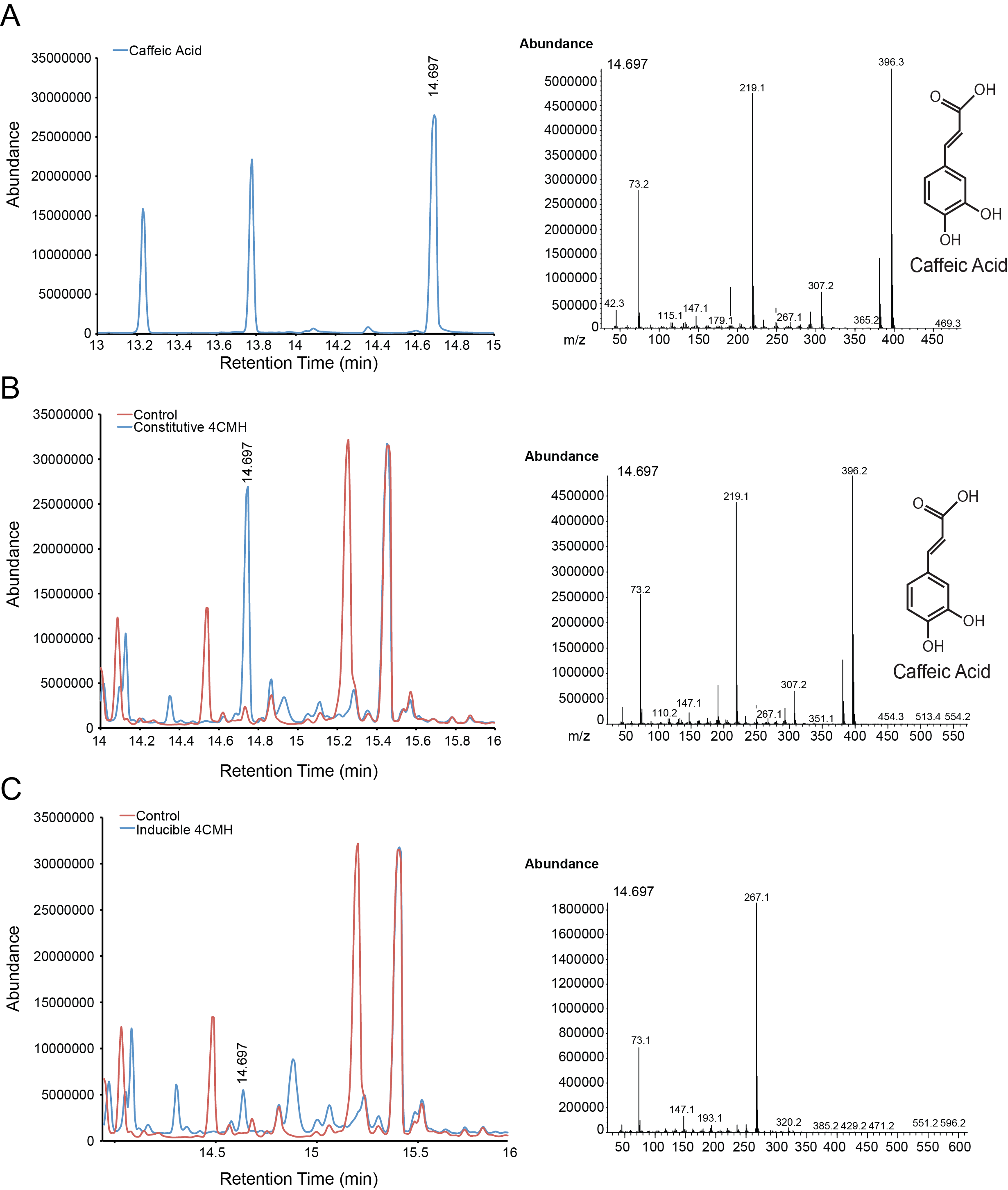

For the parts in the Vanillin biosynthetic pathway, we characterized compound generation by GC-MS for all steps in the pathway with the exception of the conversion of tyrosine to p-coumaric acid by TAL. Furthermore, we were able to show evidence of conversion for both constitutive and inducible expression for EncH, FeS and 4CMH. All compounds in these experiments were mapped to internal standards as shown. The next step is to characterize TAL and start quantifying compound generation.

Figure 1. Compound generation identification by GC-MS. Chromatograms and mass spectra for select peaks are shown. Structures represent predictions based on library matching or comparison to standards. Controls represent plasmids missing the gene of interest. A. Internal control using vanillin. B. Conversion of ferulic acid to vanillin by constitutive expressed EncH and FcS. C. Conversion of ferulic acid to vanillin by inducibly expressed EncH and FcS.

Figure 2. Compound generation identification by GC-MS. Chromatograms and mass spectra for select peaks are shown. Structures represent predictions based on library matching or comparison to standards. Controls represent plasmids missing the gene of interest. A. Internal control using ferulic acid. B. Conversion of caffeic acid to ferulic acid by a constitutively expressed COMT.

Figure 3. Compound generation identification by GC-MS. Chromatograms and mass spectra for select peaks are shown. Structures represent predictions based on library matching or comparison to standards. Controls represent plasmids missing the gene of interest. A. Internal control using caffeic acid. B. Conversion of p-coumaric acid to caffeic acid by constitutive expressed 4CMH. C. Possible conversion of p-coumaric acid to caffeic acid by inducibly expressed 4CMH. The mass spectrum however is confounded by another compound.

Figure 4. 12% SDS-PAGE of protein samples from some of the cinnamaldehyde and vanillin enzymes being expressed under the pBad promoter. No expression was detected, however, due to the detection of products from GC-MS, it is likely that the enzymes are being expressed, but not at a high enough level to detect on the gel.

1) Kaur, B.,and Chakraborty, D. (2013) Biotechnological and Molecular Approaches for Vanillin Production: a Review .Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 169, 1353-1372.

2) Priefert, H., Rabenhorst.,and Steinobuchel, A. (2001) Biotechnological production of vanillin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 56, 296-314.

3) Gill, A.O., & Holley, R.A. Mechanisms of bactericidal action of cinnamaldehyde against Listeria monocytogenes and of eugenol against L. monocytogenes and Lactobacillus sakei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5750-5755 (2004).

4) World Health Organization. (Retrieved August 2013).

5) Subash, B.P., Prabuseenivasan, S., & Ignacimuthu, S. Cinnamaldehyde--a potential antidiabetic agent. Phytomedicine. 14, 15-22 (2006).

"

"