Team:ZJU-China/Project/TheGhostKit/GhostShell

From 2013.igem.org

The Ghost Kit: Ghost Shell

Overview

In order to maintain biosafety and prolong the protein storage time, two kinds of biocompatible materials have been used to encapsulate our bacterial ghost. The first one is the calcium alginate beads, which can be observed with bare eyes (around 1mm due to production procedure). The other one is called calcium phosphate (CaP) or calcium carbonate (CaCO3) shell, which forms directly on the surface of the bacterial ghost and is slightly larger than the size of the ghost (biomineral shells: for details see Safety).

Background

The exponential rate of discovery of new antigens and DNA vaccines results in modern molecular biology and proteomics. However, the lack of effective delivery technology is a major limiting factor in their application. As a result, various non-bacterial biological delivery systems have been developed, such as the live attenuated viruses, virus-like particles and virosomes. Though they have some advantages, their capacity to encapsulate foreign antigens or DNA is restricted.

In our project, the bacterial ghost system represents a better platform technology for antigen, nucleic acid and drug delivery, owing to their intrinsic cellular and tissue tropic abilities, ease of production and the fact that they can be stored and processed without the need for refrigeration. Nevertheless, the protein the bacteria ghost has carried is still fragile to the outside, calling for a modification on the surface of bacterial ghost, so as to isolate the protein with the environment and lower the risk of protein denaturation.

Design

As have proven in Ghost sponge section, our bacterial ghost can readily pull down and purify specific proteins. One key issue raised with the pull-down assay is how we can long-term preserve the purified protein while keeping its activity uncompromised. So we came up with this idea of encapsulating bacterial ghost with different materials. By doing this, it renders us two great advantages that no other methods could have ever accomplished to our knowledge.

- It is ultra-safe for the environment. The encapsulating materials form a dense shell around the cell to prevent further leakage of protein from inside the cell. As some proteins are detrimental to the environment (such as protein toxins), this trait is extremely useful when we try to purify these proteins.

- It can prolong the protein preservation time. One important cause of proteins losing their potency is because they are degraded by protease in the harsh environment. So usually we use stringent methods to keep protein insulated from the environment which requires advanced equipment. Encapsulation is easy to perform with relatively low cost. It is an ideal alternative for protein preservation.

We first constructed bacterial ghost harboring inner-membrane scaffolds. Then we put the products and biotinylated aptamers targeting thrombin into the solution. After 30min’s incubation at 37℃, we centrifuged to obtain thrombin co-precipitated with bacterial ghost. At last, we used different materials to encapsulate the resultant products.

Material I: Alginate shells

The mechanism to form the calcium alginate beads

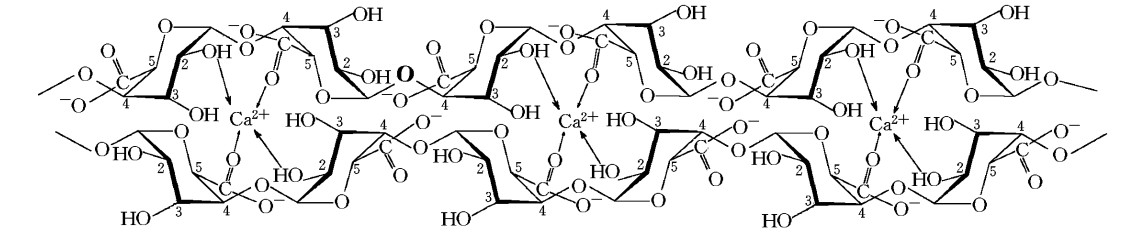

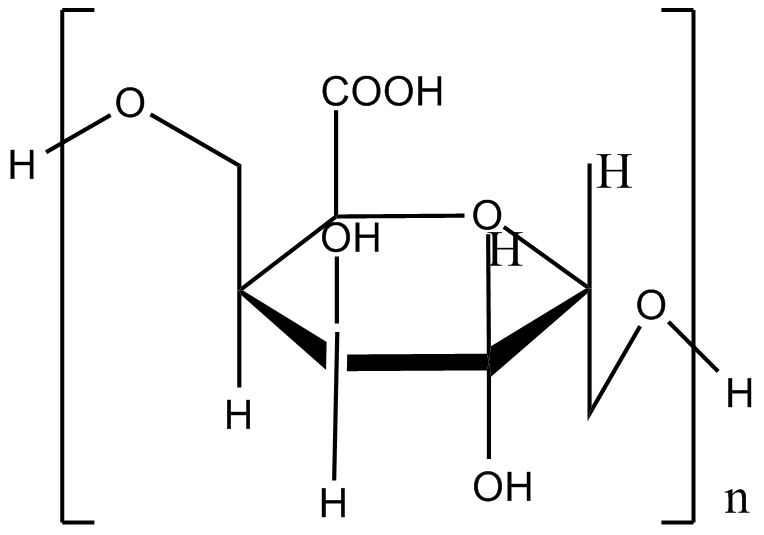

The monomers of alginate can appear in homopolymeric blocks of consecutive G-residues (G-blocks), consecutive M-residues (M-blocks) or alternating M and G-residues (MG-blocks). 5 -COOH and 2 –OH forms four coordination bonds with a single Ca2+. This agrees with the HSAB theory that calcium, which is a typical hard base, can bind well with hard acid, such as the –COOH and –OH.

Fig.1 Coordination bond formation between the calcium and alginate

The mechanism to decapsulate the calcium alginate beads

Sodium citrate is often used to decapsulate calcium alginate beads. The pKa of the guluronic acid and mannuronic acid in the alginate is 3.65 and 3.38 respectively, while the pKa1 of the citric acid is 2.41, which means that the citric acid is prior to lose a proton so as to show stronger electron density and form coordination bond with Ca2+. Sodium carbonate, sodium hydrogen phosphate and EDTA can also be used to unwrap the capsule due to similar mechanism.

Materials in use

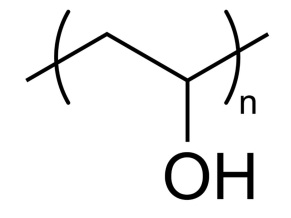

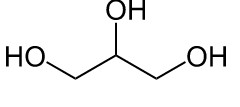

Four different materials are mixed with alginate to enhance the mechanical strength and stability of the calcium alginate beads. They are polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), chitosan, pectin and glycerol.

Material II: Biomineral shells

See safety: artificial shells for details.

Characterization

After encapsulation, SEM and TEM were used to verify the products. One day later, we decapsulate the shell to confirm the existence of thrombin by conducting western blot and activity by digestion assay.

Results

- Various alginate capsules were successfully constructed. (See Fig.2)

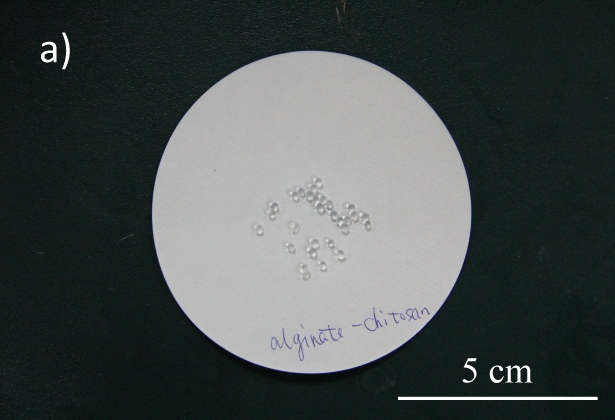

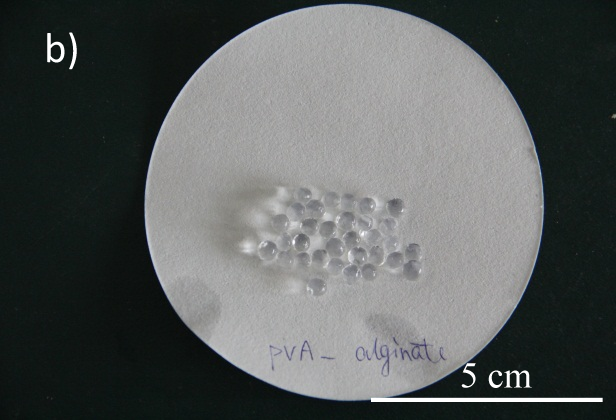

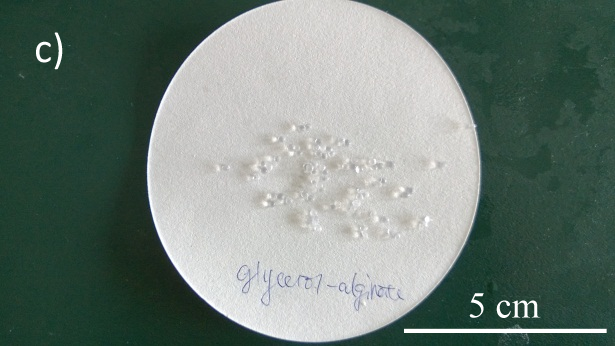

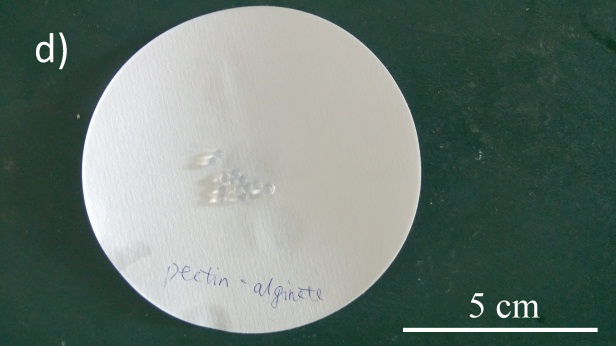

Fig.2 Alginate beads with dif ferent binding materials. a) alginate-chitosan; b) PVA-alginate; c) glycerol-alginate; d) pectin-alginate

- Thrombin remained its activity after bathing in encapsulation buffer for 2 days

- Various capsules prevented protein leakage from the cell

- Cells were successfully encapsulated with biomineral shells confirmed by SEM and TEM

Supporting information

Entrapment of whole cells in alginate

A 10 mL bacterial cell suspension was added to an alginate solution at 40◦C and mixed on a magnetic stirrer to obtain final alginate concentrations of 4% (w/v). These alginate-cell suspensions were extruded into a 0.2M CaCl2 solution to form beads with a diameter of roughly 2 mm. After gelling for 1 h, the beads were washed three times with normal saline and used for experiments.

Encapsulation of whole cells in alginate–chitosan–alginate

A 10mL bacterial cell suspension was added to an alginate solution to obtain a 1.5% (w/v) alginate concentration. The cell-alginate suspension was extruded into a 0.1 M CaCl2 solution and allowed to gel for 30 min to obtain cell containing beads. A 0.5% chitosan solution was then added to the beads at a volume ratio of 1:5 (beads:solution) to form a membrane for 10min. The membrane was then rinsed with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl to remove excess chitosan. A 0.15% alginate solution was subsequently added to counter-act remaining chitosan charges on the membrane.

At last, the gel enclosed in the alginate–chitosan–alginate membrane was liquidized with 55 mmol L−1 sodium citrate in order resulted in the ACA microcapsules with liquid cores.

Entrapment of whole cells in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)–alginate and glycerol–alginate

PVA (1 g) and sodium alginate (0.16 g)were mixed in distilled water at 80◦C. The final concentrations of PVA and sodium alginate were 5% and 0.8% (w/v) respectively (PVA:alginate ratio 6.25:1). The PVA–alginate solution was then cooled to 40◦C and mixed thoroughly with a cell suspension to obtain. Two additional ratios of PVA to alginate of 8:1.

(1.28 g PVA–0.16 g sodium alginate) and 10:1 (1.6 g PVA–0.16 g sodium alginate) were also prepared. The PVA–alginate mixtures were then extruded in a 0.2 M CaCl2 solution. The resulting beads were washed with normal saline and used for experiments.

Cell preparations and immobilization in glycerol-alginate and the ratio of glycerol to alginate were similar to those used for PVA–alginate entrapment.

Entrapment of whole cells in pectin-alginate

Pectin solutions were prepared and mixed with 5 mL of bacterial cell suspension to obtain final pectin concentrations of 4% (w/v). Afterwards, bead preparation was done in the same manner as described for alginate. Briefly, the pectin-cell suspensions were extruded in a 0.2M CaCl2 solution to form beads with a diameter of about 2mm. After gelling, the beads were washed in normal saline and used for experiments.

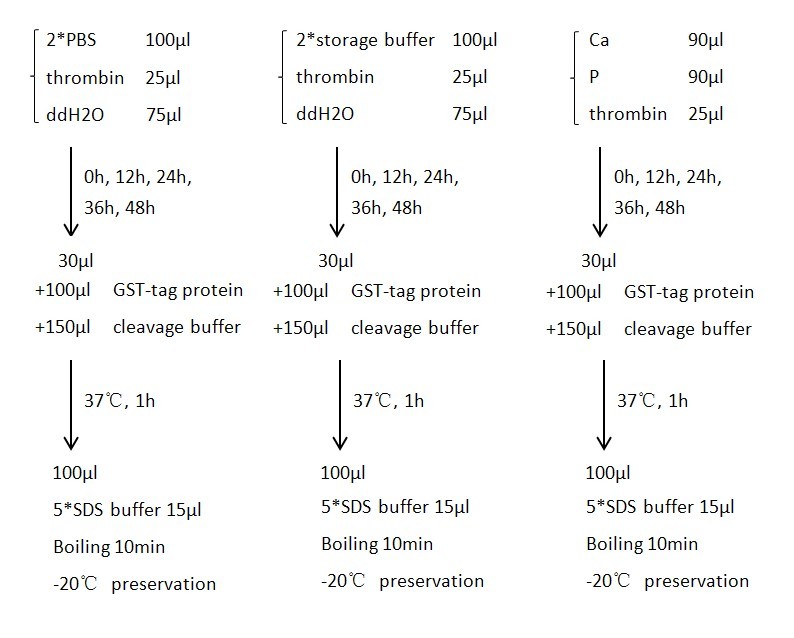

Protocols for thrombin activity test

Ingredients of Buffers

2* Thrombin Storage Buffer

100 mM sodium citrate 400 mM NaCl 0.2% PEG-8000

2* Thrombin Cleavage Buffer

40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4 300 mM NaCl 5 mM CaCl2

2* PBS

274 mM (16.02g/L) NaCl 5.4 mM (0.4g/L) KCl 20 mM (3.56g/L) Na2HPO4·2H2O 4 mM (0.54g/L) KH2PO4

References

[1] S. Rathore et al. Journal of Food Engineering. 2013, 116, 369–381

[2] M. Mollaei et al. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2010, 175, 284–292

[3] Chakameh Azimpour Tabrizi et al. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2004, 530 –537

"

"