Team:TU-Munich/Project/Killswitch

From 2013.igem.org

A novel mechanism preventing uncontrolled spread of transgenic plants

Working on plants is uncomplicated since as photoautotrophic organisms they can provide their own energy. So creating a photosensitive plant might seem silly at first glance. "Crazy, stupid Germans!", you might think, but wait, there's more! Green biotechnology does not have an easy stand in Germany due to the "German Angst" of uncontrolled spreading of transgenic plants. We therefore see it as our task and duty to meet the required high safety standards to minimize these risks for a maximum of biosafety. We created a plant that can only survive in a well-defined environment. Plants do not neccessarily need the whole spectrum of light to supply themselves with energy, so reassigning part of the spectrum to other purposes is possible. Shielded from red light by filters, the moss survives without compromising vitality or growth. Unintended release of our protected environment leads to the activation of a lethal process of no return which kills the moss.

How our red light triggered nuclease system for self-destruction works

Choosing the effector that triggers cell-death quickly and safely

Programmed Cell-Death (PCD) is a endogenous mechanism of the cell itself for controlled suicide. It is normally carried out e. g. upon tissue differentiation or due to a infection with a pathogen to prevent its propagiation.

Micococcal nuclease (also called: Thermonuclease, MNase) is a non-specific endo-exonuclease from Staphylococcus aureus which shows activity in digesting single-stranded DNA/RNA and also double-stranded DNA/RNA.

Nuclear Localization Signal/Sequence (NLS) is a short amino acid sequence of a nuclear targeted protein that is recognized by nuclear transporters, the so-called importins, and then is actively transported in the nucleus. NLS from SV40 large T antigen is mostly used to mark synthetic proteins for nuclear localization.

In plants, the regulation and mechanism of programmed cell-death (PCD) is not yet fully understood, but analoguely to all other eukaryotic organisms it is known that the fragmentation of the genomic DNA inevitably leads to PCD.

We chose the Micrococcal nuclease ([http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1159105 BBa_K1159105]) as effector to destroy the integrity of the genomic DNA. Since the genome is protected by the nuclear envelope, it was necessary to tag the nuclease with a Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) ([http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1159109 BBa_K1159109]). Nucleases show their death-bringing activity already at low concentrations. It was therefore essential to put the kill-switch under tight spatio-temporal control and induce activity under specific conditions only.

Preventing the nuclease from developing its deadly potential under well-defined conditions

Transmembrane Domain (TMD) is the region of a membrane protein which traverses the plasma membrane.

TEV Protease is a site-specific cystein protease from the C4 peptidase family from Tabacco Etch Virus (TEV). Its typical recognition site is ENLYFQ(G/S).

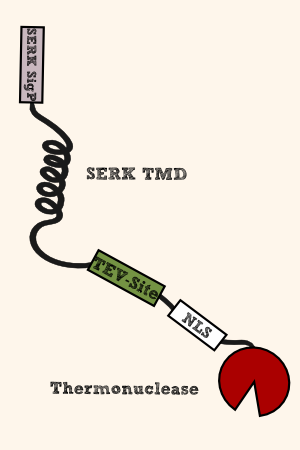

We adress the problem by anchoring the nuclease in the cytoplasmatic membrane under basal conditions. In its membrane-associated form ([http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1159111 BBa_K1159111]), the nuclease cannot evolve its deadly potential as it is spatially seperated from its site of action: In eukaryotic organisms the genomic DNA is subcellular located in the nucleus, sheltered by the nuclear envelope.

To make the nuclease releasable, we designed a long linker with a TEV recognition/cleavage site between the transmemmbrane domain (TMD) and the NLS-tagged nuclease. In the presence of TEV protease activity, the nuclease is liberated from the membrane and translocates into the nucleus due to its NLS tag. There, it can fulfill its task as the executor of PCD by degrading the DNA with its endo-exonuclease activity.

The question is how to enable the lethal activity of the nuclease upon red light illumination? The first component consists a fusion protein composed of a signal peptide plus transmembrane region of Physcomitrella patens (see here and here) for membrane localization, a TEV cleavage site for cleaving off the nuclease upon red light exposition and nuclear localizaton signal plus the nuclease itself as the death bringing part.

Red light triggered reconstitution of split TEV Protease

Split TEV Protease is a split version of the TEV Protease which N- and C-terminal split parts shows no enzymatic activity. Bringing them to physical proximity leads to reconstitution of the cleavage activity.

Phytochrome B (PhyB) is a plant photoreceptor that exists in two interconvertible forms Pr and Pfr. In its Pfr (far red light sensititve) form upon red light illumination, PhyB interacts with Phytochrome Interacting Factors, e.g. PIF3 or PIF6.

Phytochrome Interacting Factor 3/6 (PIF3/PIF6) are both transcription factors with basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) motifs that that bind to PhyB upon red light exposition

As mentioned, the nuclease is normally localized at the cytoplasmatic membrane and by cleavage through a TEV protease, the NLS-tagged nuclease is released from its cage and goes directly in the nucleus.

To liberate the nuclease after exposition to red light, we designed two fusion proteins; each of them contains either the N-terminal or the C-terminal splitted part of the TEV protease. The splitted TEV protease is not active as long as the catalytic residues are seperated. The first fusion protein has PhyB as its fusion partner which heterodimerizes with PIF3/PIF6, the fusion partner of the second fusion protein. Red light induces heterodimerization of PhyB with PIF3/PIF6 and thus reconstitutes the N- and C-terminal half of the TEV Protease resulting in a proteolytic activity for a specific TEV recognition site.

The reconstituted TEV Protease libarates the nuclease from its membrane anchor by cleaving it off from the transmembrane domain. The nuclear localization signal ensures nuclear translocation of the nuclease.

Reaching the nucleus, the nuclease can unfold its full deadly impact by digest the genomic DNA in fragments through its endo-exonuclease activity. Genomic fragmentation automatically triggeres endogenous programmed cell-death.

Key features of the system

During the design process of the kill-switch we developed a set of key features that we thought to be essential for the efficient activation of programmed cell death.

- Signal transduction solely on protein level: By excluding transcriptional/translational transduction from the system we created a system that can assure PCD with tight temporal control. This design eliminates the risk of a negative feedback loop that would appear when transcriptional/translational efficiency is hampered due to lowered cell vitality. See: Modeling.

- Strong lethal activity: By destroying the genetic material of a cell, the nuclease ensures a quick, non-reversible, inevitable programmed cell death.

- Cheap, non-toxic, automatic induction: Activation by light eradicates the need for expensive, possibly toxic inductors and even of any human interaction to prevent the release of genetically modified moss.

Design Notes

Releasable Membrane-associated Endo-exonuclease

For our membrane bound nuclease we have to choose a nuclease with following characteristics:

- Our nuclease should digest any DNA wihtout any preferences for recognitions sites

- Furthermore, that nuclease should not have disulfide bonds as they cannot be formed outside in the cytoplasmatic compartment.

Micrococcal nuclease ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159105 BBa_K1159105]) (alias S7 Nuclease, MNase, Thermonuclease) from Staphylococcus aureus was chosen as our death bringing executor as it fulfills our requirements (see above). It shows endo-exonuclease activity for DNA and does not contain any disulfid bonds.

To anchor the nuclease in the cytoplasmatic membrane, we use the TMD ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159315 BBa_K1159315]) and the N-terminal signal peptide ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159303 BBa_K1159303]) from the chassis Physcomitrella patens itself.

To make the nuclease releasable from the membrane in the presence of TEV protease activity, we designed a long linker with a TEV recognition and cleavage site. We designed a long linker (GlyGlyGlyGlySer)x5 with TEV cleavage site at the C-terminal end of the linker ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159310 BBa_K1159310]).

After beeing released from the membrane cage through the cleavage by TEV proteolysis, the nuclease has be guided to its site of action, the nucleus. For this purpose, we are using the NLS from SV40 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K801030 BBa_K801030]).

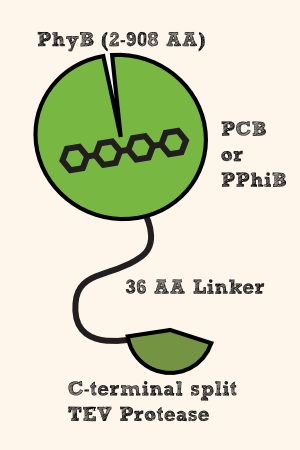

Red light triggered C-terminal Split-TEV Protease

For the first part of the light-induced reassembling of split TEV protease, we use the first 908 N-terminal amino acids ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K801031 BBa_K801031]) for the reversible heterodimerization with PIF3/PIF6. It has been reported that the first 650 N-terminal amino acids indeed are sufficient for photoconversion of Pr (inactive form) to Pfr but are irreversible, so we take the first 908 N-terminal amino acids, which has been proven to be reversible by illumination with far red light. For its function as a light-switchable protein, PhyB needs a essential chromophore, phycocyanobilin (PCB) or phytochromobilin (PPhiB), which is autocatycally incorporated. The latter chromophore phytochromobilin is endogenous avaible in Physcomitrella patens, so we do not have to implement the biosynthesis pathway for one of the chromophores.

We have also first to consider how the fusion parts can be fused together and which parts work as N- or C-parts. It has been reported that PhyB should be used as N-part. The first 100 amino acids of PIF3 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159103 BBa_K1159103])/PIF6 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159104 BBa_K1159104]) on the other side can either be used at the N- and C-terminus. The N-terminal half of TEV protease also can be used as N- or C-terminal fusion part. On the other side the C-terminal half of the TEV protease should be used only as C-terminal fusion protein because the C-terminus is in the proximity to the catalytic site.

Another important question is to choose the length that links the light-associated proteins with the split-TEV protease halfs together. After looking at the predicted structure of PhyB (I-TASSER and HHpred) and the crystal structure of the TEV protease we decided to use a 36 amino acids long flexible linker (GSAT linker, [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K243029 BBa_K243029]) to allow the splitted halfs of the TEV protease to reassemble with each other.

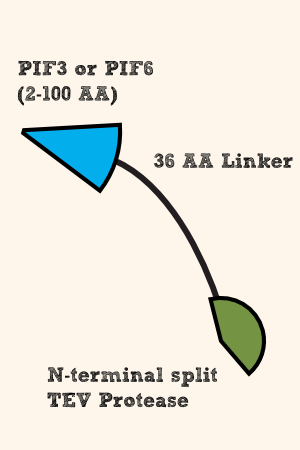

Red light triggered N-terminal Split-TEV Protease

For the second part of the light triggered reassembling of the splitted TEV Protease, we use PIF3 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159103 BBa_K1159103]) and PIF6 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159104 BBa_K1159104]) as the protein part that is recognized and bound by PhyB upon red light irradiation. Literature shows that PIF6 is bound with a higher affnity than PIF3 by PhyB.

To link the N-terminal half of the TEV Protease ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159101 BBa_K1159101]) to PIF3/PIF6, we also choose the same linker (GSAT linker, [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K243029 BBa_K243029]) as we used it for the linkage of PhyB with the C-terminal half of TEV Protease.

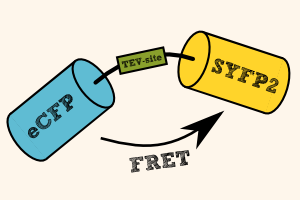

FRET Reporter for TEV Protease activity

To prove that our light-switchable TEV Protease is actually working, we designed a FRET reporter ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159112 BBa_K1159112]). The FRET reporter is composed of two chromoproteins, namely eCFP ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159302 BBa_K1159302]) and SYFP2 ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159301 BBa_K1159301]), which are linked together through a short linker with an internal TEV cleavage site ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159318 BBa_K1159318]).

As a functional FRET pair, eCFP emits its energy after irradiation through Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) to SYFP2 due to the overlap of the emitting spectra of eCFP and the excitation spectra of SYFP2.

In the presence of TEV Protease activity, the TEV cleavage site is recognized and processed, resulting in the seperation of the FRET pair eCFP and SYFP2. Thus, we will observe a increase of the emission spectra of eCFP and a decrease of the emission spectra of SYFP2.

Polycistronic expression in Eukaryotes

For creating the red light sensitive kill switch, we have to constitutively express 3 fusion proteins: 2 proteins for the light switchable TEV Protease and 1 for the membrane-anchored nuclease.

The classical approach would be to flank the parts with an upstream promoter and a downstream terminator. To avoid this inconvenient complication, we decided to use the 5'UTR of Poliovirus 1 Mahoney strain containing a cap-independent Internal Ribosome Entry Site ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1159300 BBa_K1159300]) for polycistronic expression of our proteins. This strategy enables us to put multiple CDSs under the control of only one promoter and one terminator, by simply inserting the IRES in between.

References:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1896431 Hynes et al., 1991 Hynes TR, Fox RO (1991). The crystal structure of staphylococcal nuclease refined at 1.7 A resolution. Proteins. 10(2):92-105

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6020427 Heins et al., 1967 Heins JN, Suriano JR, Taniuchi H, Anfinsen CB. (1967). Characterization of a nuclease produced by Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem., 242(5):1016-20

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19749742 Levskaya et al., 2009 Levskaya, A., Weiner, O. D., Lim, W. A., and Voigt, C. A. (2009). Spatiotemporal control of cell signalling using a light-switchable protein interaction. Nature, 461(7266):997–1001.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12355112 Mendelsohn, 2002 Mendelsohn, A. R. (2002). An enlightened genetic switch. Nat Biotechnol, 20(10):985–7

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12219076 Shimizu-Sato et al., 2002 Shimizu-Sato, S., Huq, E., Tepperman, J. M., and Quail, P. H. (2002). A light-switchable gene promoter system. Nat Biotechnol, 20(10):1041–4

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17072307 Wehr MC et al., 2006 Wehr MC, Laage R, Bolz U, Fischer TM, Grünewald S, Scheek S, Bach A, Nave KA, Rossner MJ (2006). Monitoring regulated protein-protein interactions using split TEV. Nat Methods, 3(12):985-93

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19021876 Gitzinger et al., 2009 Gitzinger M, Parsons J, Reski R, Fussenegger M (2009). Functional cross-kingdom conservation of mammalian and moss (Physcomitrella patens) transcription, translation and secretion machineries. Plant Biotechnol J. 7(1):73-86.

"

"

AutoAnnotator:

Follow us:

Address:

iGEM Team TU-Munich

Emil-Erlenmeyer-Forum 5

85354 Freising, Germany

Email: igem@wzw.tum.de

Phone: +49 8161 71-4351