Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Biosafety/Biosafety System L

From 2013.igem.org

Biosafety System Lac of Growth

Overview

The Biosafety-System Lac of Growth <bbpart>BBa_K1172911</bbpart> is an improvement of the BioBrick <bbpart>BBa_K914014</bbpart> by replacing the first promoter PBAD into the rhamnose promoter PRha and the integration of the alanine racemase (alr) <bbpart>BBa_K1172901</bbpart>. The transcription of the Barnase is regulated by the lac promoter and therefore LacI is used as repressor. The Plac promoter is characterized by a high basal transcription so that there is a high lethality rate in this systems. But as there are different challenging opportunities to overcome this problem it is also an interesting Biosafety-System with a high potential use.

Genetic Approach

Rhamnose promoter PRha

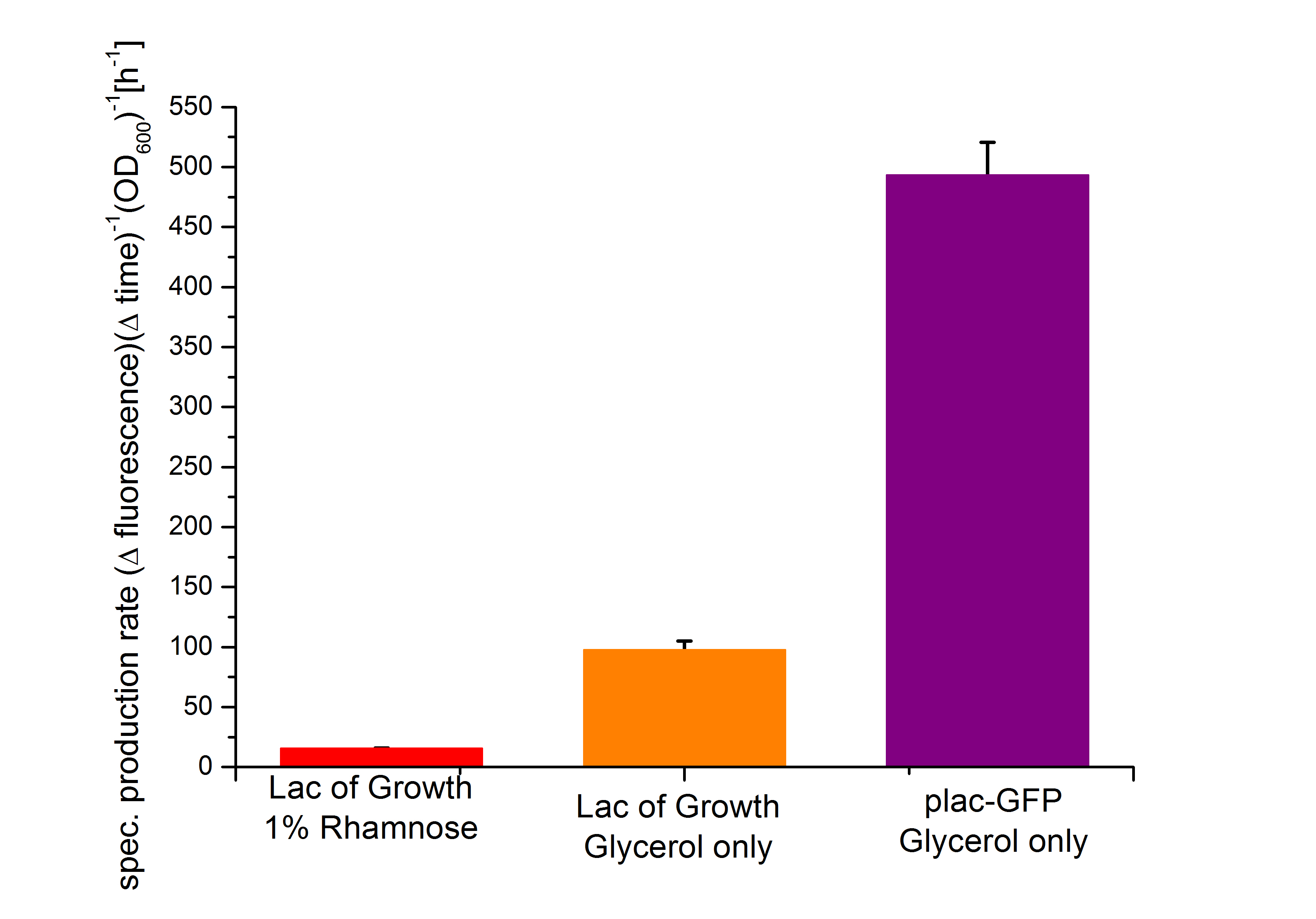

The promoter PRha (<bbpart>BBa_K914003</bbpart>) naturally regulates the catabolism of the hexose L-rhamnose. The advantage to use this promoter is its solely positive regulation. The regulon consists of the gene rhaT for the L-rhamnose transporter and the two operons rhaSR and rhaBAD.

The operon rhaSR encodes the two transcriptional activators RhaS and RhaR, who are responsible for the positive activation of the L-rhamnose catabolism, while the operon rhaBAD encodes the genes for the direct catabolism of L-rhamnose.

When L-rhamnose is present, it acts as an inducer by binding to the regulatory protein RhaR. RhaR regulates its own expression and the expression of the regulatory gene rhaS by repressing or, in the presence of L-rhamnose, activating the operon rhaSR. Normally, the expression level is modest, but it can be enhanced by a higher level of intracellular cAMP, which increases in the absence of glucose. So, in the presence of L-rhamnose and a high concentration of intracellular cAMP, the activator protein RhaR is expressed on higher level, resulting in an activation of the promoter PrhaT for an efficient L-rhamnose uptake and an activation of the operon rhaBAD. The L-rhamnose is than broken down into dihydroxyacetone phosphate and lactate aldehyde by the enzymes encoded by rhaBAD (Wickstrum et al., 2005).

A brief schematic summary of the regulation is shown in Figure 1.

Dihydroxyacetone phosphate can be metabolized in the glycolysis pathway, while lactate aldehyde is oxidized to lactate under aerobic conditions and reduced to L-1,2,-propandiol under anaerobic conditions.

The degradation of L-rhamnose can be separated in three steps. In the first step the L-rhamnose is turned into L-rhamnulose by an isomerase (gene rhaA). L-rhamnulose is in turn phosphorylated to L-rhamnulose-1-phosphate by a kinase (gene rhaB) and the sugar phosphate is finally hydrolyzed by an aldolase (gene rhaD) to dihydroxyacetone phosphate and lactate aldehyde (Baldoma et al., 1988).

For our Safety-System Lac of Growth, the rhamnose promoter PRha is used to control the expression of the repressor LacI and the essential alanine racemase, because this promoter has an even lower basal transcription then the arabinose promoter PBAD. This is needed to tightly repress the expression of the alanine racemase (alr) and thereby take advantage of the double-kill switch. Although the rhamnose promoter PRha is characterized by a very low basal transcription it can not be used for the control of the toxic RNase Ba (Barnase), which ist needed for the alanine racemase (alr), the other part of the double-kill switch. In conclusion this promoter is the best choice for the first part of the Biosafety-System, as it is tightly repressed in the absence of L-rhamnose, but activated in its presence.

Repressor LacI

Naturally the lacZYA operon encodes the genes for the direct catabolism of the disaccharide lactose in E. coli. The operon contains the lactose promoter Plac and the genes for the catabolism of lactose to glucose and galactose. Upstream of the lac operator, in opposite orientation, the coding sequence for the repressor LacI under the control of a weak promoter is located (Jacob et al., 1961).

Compared to the catabolism of the sugars L-rhamnose or L-arabinose, lactose, as a disaccharide has a higher energy content and is therefore preferably used. For this reason the basal transcription of this promoter is higher than that of PRha. The leakiness of the lac promoter is caused by the fact that LacY needs to be expressed for an efficient lactose uptake, while the uptake in the arabinose system is regulated separately (Görke et al., 2008).

In our Safety-System the LacI (<bbpart>BBa_C0012</bbpart>) is used for repression of the lactose promoter Plac.

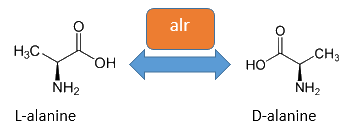

Alanine racemase Alr

The alanine racemase Alr (EC 5.1.1.1) from the Gram-negative enteric bacteria Escherichia coli is an isomerase, which catalyses the reversible conversion of L-alanine into the enantiomer D-alanine (see Figure 2). For this reaction, the cofactor pyridoxal-5'-phosphate (PLP) is necessary. The constitutively expressed alanine racemase (alr) is naturally responsible for the accumulation of D-alanine. This compound is an essential component of the bacterial cell wall, because it is used for the cross-linkage of peptidoglycan (Walsh, 1989).

The usage of D-alanine instead of a typically L-amino acid prevents cleavage by peptidases. However, a lack of D-alanine causes to a bacteriolytic characteristics. In the absence of D‑alanine dividing cells will lyse rapidly. This fact is used for our Biosafety-Strain, a D-alanine auxotrophic mutant (K-12 ∆alr ∆dadX). The Biosafety-Strain grows only with a plasmid containing the alanine racemase (<bbpart>BBa_K1172901</bbpart>) to complement the D-alanine auxotrophy. Consequently the alanine racemase is essential for bacterial cell division. This approach guarantees a high plasmid stability, which is extremely important when the plasmid contains a toxic gene like the Barnase. In addition this construction provides the possibility for the implementation of a double kill-switch system. Because if the expression of the alanine racemase is repressed and there is no D-alanine supplementation in the medium, cells will not grow.

Terminator

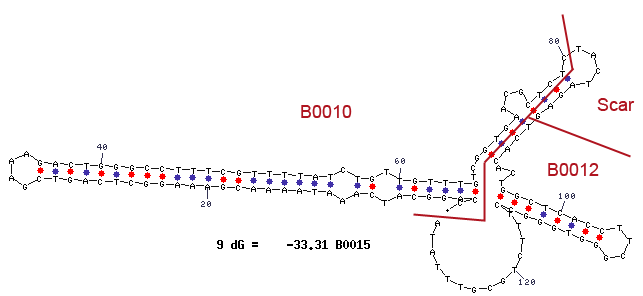

Terminators are essential to terminate the transcription of an operon. In procaryotes two types of terminators exist. The rho-dependent and the rho-independent terminator. Rho-independent terminators are characterized by their stem-loop forming sequence. In general, the terminator-region can be divided into four regions. The first region is GC-rich and constitutes one half of the stem. This region is followed by the loop-region and another GC-rich region that makes up the opposite part of the stem. The terminator closes with a poly uracil region, which destabilizes the binding of the RNA-polymerase. The stem-loop of the terminator causes a distinction of the DNA and the translated RNA. Consequently the binding of the RNA-polymerase is cancelled and the transcription ends after the stem-loop (Carafa et al., 1990).

For our Bioafety-System Lac of Growth the terminator is necessary to avoid that the expression of the genes under control of the rhamnose promoter PRha, like the Repressor LacI and the alanine racemase (alr) results in the transcription of the genes behind the lactose promoter PLac which contains the toxic Barnase <bbpart>BBa_K1172904</bbpart> and would lead to cell death.

Lactose promoter Plac

Naturally the lacZYA operon encodes the genes for the direct catabolism of the disaccharide lactose in E. coli. The operon consists of a CAP-binding site, the lac promoter, the lac operator and the genes lacZ, lacY and lacA downstream of the promoter. The transcription of the lactose promoter is regulated by the LacI repressor, whose coding sequence is found upstream of the lacZYA operon under control of a weak promoter (Figure 4).

In the absence of lactose the transcription of the genes behind the lactose promoter is blocked, caused by the binding of the LacI repressor. In the presence of lactose the repressor is released from the operator sequence and so the genes can be transcribed. Typically the transcription is enhanced by a high intracellular level of cAMP (Busby, 1999).

The lactose promoter thereby regulates the transcription of the genes lacZ, lacY and lacA. lacZ encodes ß-galactosidase, an enzyme, which breaks down lactose to glucose and galactose. Additionally ß-galactosidase catalyzes the degradation of lactose to allolactose. By binding to the LacI repressor, allolactose changes the conformation of LacI. Thereupon, the repressor is not able to bind to the operator sequence and so the transcription is not blocked any more. As only one enzyme is necessary to gain a substrate for glycolysis it becomes clear, why the degradation of lactose is more preferable compared to L-arabinose or L-rhamnose.

Lactose, as a disachharide has a higher energy content. Hence, the cell needs to ensure the proper catabolism of lactose, which leads to a less tight regulation of the lac operon. This is caused by the fact that the lacY gene, coding for the integral membrane protein lactose permease, is necessary for the lactose uptake and has to be transcribed on a low level.

The last gene of the lacZYA operon, lacA, encodes for a transacetylase, which acetylizes glycosides that cannot be metabolized. The acetylated glycosides are transported outside the cell to avoid their accumulation in the cell.

In our Biosafety-System the lac promoter is used to regulate the expression of the Barnase. Because the native lac promoter shows a high basal transcription in comparison to the other promoters used, it might be not ideal for the regulation of a toxic gene product. Nevertheless the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth is ideal for the comparison of the basal transcription with other Biosafety-Systems and the leakiness of the lac promoter might be reduced by adding a second LacI-binding site 12 nt downstream of the existing binding site. As this distance corresponds to about one helix turn of the double helix, this should allow an additional LacI repressor to bind on the other site of the DNA and tighten the repression of the lactose promoter. Furthermore, the efficiency of the toxic gene product might be lower than expected, so that a higher basal transcription and activation may be needed. It can be concluded that the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth is a promising Biosafety-System (Lewis, 2005).

RNase Ba (Barnase)

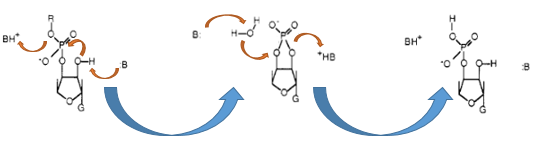

The Barnase (EC 3.1.27) is a 12 kDa extracellular microbial ribonuclease, which is naturally found in the Gram-positive soil bacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and consists of a single chain of 110 amino acids. The Barnase (RNase Ba) catalyses the cleavage of single stranded RNA, preferentially behind Gs. In the first step of the RNA-degradation a cyclic intermediate is formed by transesterification and afterwards this intermediate is hydrolyzed yielding in a 3'-nucleotide (Mossakowska et al., 1989).

In Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, the activity of the Barnase (RNase Ba) is inhibited intracellular by an inhibitor called barstar. Barstar consists of only 89 amino acids and binds with a high affinity to the toxic Barnase. This prevents the cleavage of the intracellular RNA in the host organism (Paddon et al., 1989). Therefore the Barnase normally acts only outside the cell and is translocated under natural conditions. For the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth we modified the enzyme by cloning only the sequence responsible for the cleavage of the RNA, leaving out the N-terminal signal peptide part.

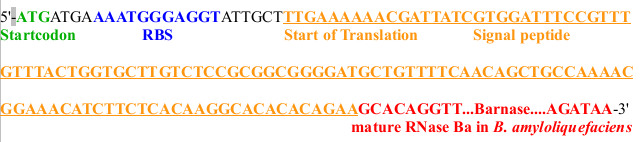

As shown in Figure 6 below, the transcription of the DNA, which encodes the Barnase produces a 474 nt RNA. The translation of the RNA starts about 25 nucleotides downstream from the transcription start and can be divided into two parts. The first part (colored in orange) is translated into a signal peptide at the amino-terminus of the Barnase coding RNA. This part is responsible for the extracellular translocation of the RNase Ba, while the peptide sequence for the active Barnase starts 142 nucleotides downstream from the transcription start (colored in red).

For the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth, we only used the part (<bbpart>BBa_K1172904</bbpart>) of the Barnase encoding the catalytic domain without the extracellular translocation signal of the toxic gene product. Translation of the barnase gene leads to rapid cell death if the expression of the Barnase is not repressed by the repressor LacI of our Biosafety-System.

Biosafety-System Lac of Growth

Combining the genes described above with the Biosafety-Strain K-12 ∆alr ∆dadX results in a powerful device, allowing us to control the bacterial cell division. The control of the bacterial growth is possible either active or passive. Active by inducing the PLac promoter with IPTG or classically with lactose and passive by the induction of L-rhamnose. The passive control makes it possible to control the bacterial cell division in a defined closed environment, like the MFC, by continuously adding L-rhamnose to the medium. As shown in Figure 7 below, this leads to an expression of the essential alanine racemase (alr) and the LacI repressor, so that the expression of the RNase Ba is repressed.

In the event that bacteria exit the defined environment of the MFC or L-rhamnose is not added to the medium any more, both the expression of the alanine Racemase (Alr) and the LacI repressor decrease, so that the expression of the toxic RNase Ba (Barnase) begins. The cleavage of the intracellular RNA by the Barnase and the lack of synthesized D-alanine, caused by the repressed alanine racemase inhibit the cell division. Through this it can be secured that the bacteria can only grow in the defined area or the device of choice respectively.

Results

Characterization of the lactose promoter Plac

First the lactose promoter PLac was characterized to get a first impression of its basal transcription rate. Therefore the bacterial growth was investigated under the pressure of the unrepressed Plac promoter on different carbon source using M9 minimal medium with either glucose or glycerol. The transcription rate was identified by fluorescence measurement of GFP <bbpart>BBa_E0040</bbpart> behind the Plac promoter using the BioBrick <bbpart>BBa_K741002</bbpart>.

As shown in Figure 9 below, the bacteria grew better on glucose then on glycerol. This is due to glucose being the better energy source of these two, because glycerol enters glycolysis at a later step and therefore delivers less energy. Moreover an additional ATP consumption is needed to drive glycerol uptake. For the investigation of the basal transcription the fluorescence measurements, shown in Figure 10, is more interesting.

It can be demonstrated that the fluorescence differs corresponding to the carbon source used. The difference it not that high as observed for the arabinose promoter PBAD. But in comparison to the tetO operator the difference is still obvious. This shows that the transcription of the lac promoter depends on the intracellular cAMP level, but is not as effective as the arabinose promoter PBAD. So growth on glucose does not cause an additional induction of the lactose promoter Plac, while growth on glycerol does. In the presence of glucose, the intracellular concentration of cAMP is low. The absence of cAMP results in inactive CAP (carbon utilization activator protein) and thus no induction of more inefficient catabolic routes, like the catabolism of lactose. Therefore, glucose is catabolized first by the bacteria, resulting in an optimal growth. In the absence of glucose, the cAMP level increases which enhances via CAP-cAMP the transcription of most operons encoding enzymes for the catabolism of alternative carbon sources. Therefore, the expression of GFP under the control of the Plac promoter increases on glycerol.

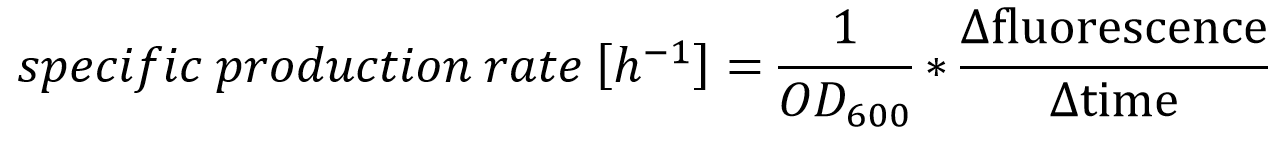

The effect that glucose represses the transcription of the Plac promoter becomes more obvious by calculating the specific production rates of GFP, as shown in Figure 11. The specific production rates were calculated via equation (1) :

With the calculation of the specific production rate of GFP it can be demonstrated that the GFP synthesis rates differ between the cultivation on glucose and glycerol. The specific production rate is low, when using glucose as carbon source, but shows a higher more unstable level in the cultivation with glycerol.

Because the specific production rate was calculated between every single measurement point, the curve in Figure 11 is not smoothed and so the fluctuations have to be ignored, as they do not stand for real fluctuations in the expression of GFP. They are caused by measurement variations in the growth curve and the fluorescence curve. And as neither of this curves are ideal, the fluctuations are the result. Nevertheless this graph shows the difference between the two carbon sources.

Characterization of the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth

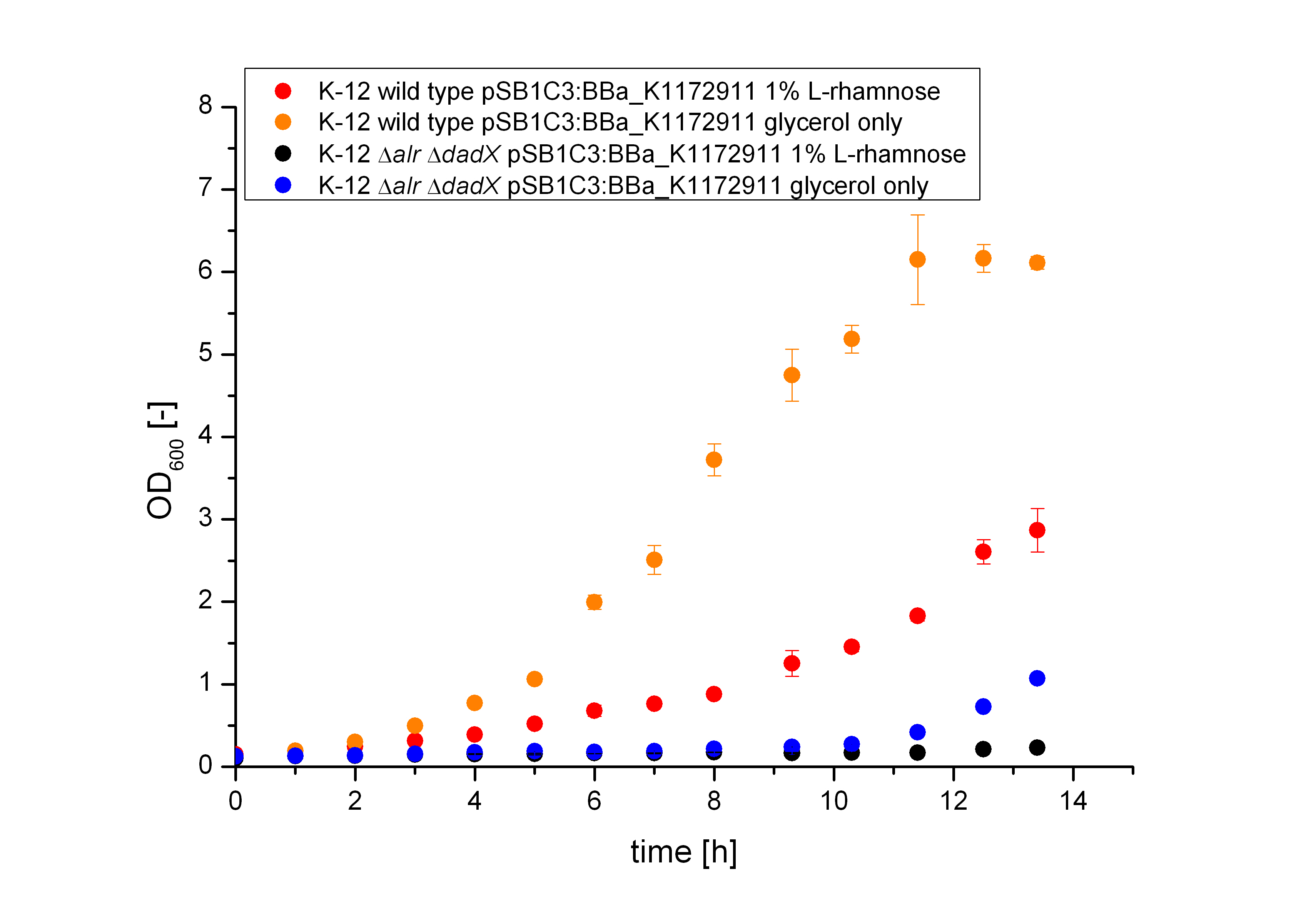

The Biosafety-System Lac of Growth was characterized on M9 minimal medium using glycerol as carbon source. As for the characterization of the pure lactose promoter Plac above, the bacterial growth and the fluorescence of GFP <bbpart>BBa_E0040</bbpart> was measured. Therefore, the wild type and the Biosafety-Strain E. coli K-12 ∆alr ∆dadX both containing the Biosafety-Plasmid <bbpart>BBa_K1172911</bbpart> were cultivated once with the induction of 1% L-rhamnose and once only on glycerol.

It becomes obvious (Figure 12) that the bacteria, induced with 1 % L-rhamnose (red and black curve) grow obviously slower, than on pure glycerol (orange and blue curve). This might be attributed to the high metabolic burden encountered by the induced bacteria. The expression of the repressor LacI and the alanine racemase (Alr) simultaneously causes a high stress on the cells, so that they grow slower than the uninduced cells which express only GFP. Additionally, it can be observed, that the Biosafety-Strain E. coli K-12 ∆alr ∆dadX shows a very long lag-phase.

The long lag-phase and the high measured fluorescence can not be explained so far, as the wild type shows normal grow. So further cultivation of the Biosafety-Strain containing the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth are necessary. In contrast the fluorescence of the wild type containing the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth shows the expected characteristics. It can be observed that the fluorescence of GFP increases in the cultivation on pure glycerol, while it is reduced by the induction of 1% L-rhamnose.

From the data presented above it cannot be determined if the expression of the repressor LacI does affect the transcription of GFP or not. Considering the wild type containing the Biosafety-System, the slower growth is a first indication that the repressor lacI and the alanine racemase (Alr) are highly expressed, but the growth of the bacteria shows nearly the same kinetics as the fluorescence. So it could be possible that the repressor does not affect the expression level of GFP under the control of the lactose promoter Plac. This becomes more clear by the calculation of the specific production rate of GFP by equation (1) . As shown in Figure 14 below the specific production rate differs between the uninduced Biosafety-System and the Biosafety-System induced by 1% L-rhamnose.

The production of GFP in the presence of L-rhamnose (red curve) is always lower than in its absence (orange curve), so that the expression of GFP is repressed in the presence of L-rhamnose.

Only at the end, the GFP synthesis of the uninduced cultivations seems to be lower. This might be caused by the very fast cell division in the end of the exponential phase, so that cells grow much faster, than expressing GFP.

Because the specific production rate of GFP was calculated between every single measurement point, the curve in Figure 14 is not smoothed and so the fluctuations have to be ignored, as they do not stand for real fluctuations in the expression of GFP. They are caused by measurement variations in the growth curve and the fluorescence curve. But there is a tendency that the production of GFP is lower when the bacteria are induced with 1% L-rhamnose. So the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth seems to work.

Conclusions

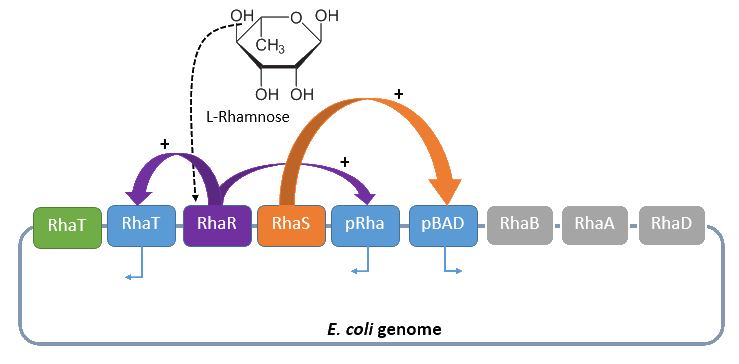

It could be demonstrated that the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth works in principle. For example, the expression level of GFP decreased in the presence of L-rhamnose, as can be seen in Figure 15 the specific production rates of GFP after 7,5 hours are compared within the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth. The induction of the Biosafety-System with L-rhamnose leads to a tight repression of the expression of GFP (red bar) when compared to the uninduced state (orange bar). But the level of gene expression is still quite high.

The Biosafety-System Lac of Growth works quite well, but in comparison to the other Biosafety-Systems it shows a higher basal transcription in the uninduced cultivation. So this might result in a high lethality rate, when using the toxic Barnase <bbpart>BBa-K1179204</bbpart> instead of GFP. Although this could also be useful for Biosafety-Systems with a lower toxicity than the RNase Ba, the basal transcription could also be reduced by a double lac promoter with two LacI binding sites.

But a number of problems remain to be fixed. For example, the basal expression of LacI under uninduced conditions is too high. This becomes evident when comparing GFP expression in the uninduced Biosafety-System (orange bar) to the uninduced second part of the Biosafety-System <bbpart>BBa_K741002</bbpart> (purple bar). The strong reduction of GFP expression is likely caused by the basal transcription of the first part of the Biosafety-System containing the LacI repressor which causes a tighter repression of the Plac promoter, while there is no sufficient amount of LacI in the strain carrying the second part only.

Another improvement of the Biosafety-System could be to adjust the plasmid copy number. The plasmid pSB1C3 we used for the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth <bbpart>BBa_K1172911</bbpart> is a high copy plasmid, resulting in 100 – 300 copies of the plasmid in each cell. Therefore it could be worthwhile to clone the Biosafety-System into a medium (15 – 20 copies) or even a low copy plasmid (2 – 12 copies) to take advantage of the double-kill switch on one hand, and to reduce the metabolic pressure triggered by the plasmid on the other hand. Moreover the lower plasmid copy number might simplify the integration of the Barnase instead of GFP. Nevertheless the Biosafety-System Lac of Growth we constructed can already be used as a kill-switch Biosafety-System and is characterized by a higher plasmid stability compared to common Biosafety-Systems.

References

- Baldoma L and Aguilar J (1988) Metabolism of L-Fucose and L-Rhamnose in Escherichia coli: Aerobic-Anaerobic Regulation of L-Lactaldehyde Dissimilation [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC210658/pdf/jbacter00179-0434.pdf|Journal of Bacteriology 170: 416 - 421.].

- Busby S, Ebright RH (1999) Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP).[http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0022283699931613/1-s2.0-S0022283699931613-main.pdf?_tid=a8f22b74-2cf4-11e3-9457-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1380891687_f17fd24e5a3e15da96493226fdcaaa10|Journal of molecular biology 239: 199 - 213.].

- Carafa, Yves d'Aubenton Brody, Edward and Claude (1990) Thermest Prediction of Rho-independent Escherichia coli Transcription Terminators - A Statistical Analysis of their RNA Stem-Loop Structures [http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0022283699800059/1-s2.0-S0022283699800059-main.pdf?_tid=ede07e2a-2a92-11e3-b889-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1380629809_2d1a59e395fc69c8608ab8b5aea842f7|Journal of molecular biology 3: 835 - 858].

- Casali, N., Preston A. (2003) E. coli Plasmid Vectors - Methods and Applications [http://www.springerprotocols.com/BookToc/doi/10.1385/1592594093 Methods in Molecular Biology 235].

- Görke, Boris and Stülke, Jörg (2008) Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients [http://www.nature.com/nrmicro/journal/v6/n8/full/nrmicro1932.html|Nature Reviews Microbiology 6: 613 - 624].

- Jacob, F Monod J (1961) Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13718526|Journal of molecular biology 216: 318 - 356].

- Lewis, Mitchell (2005) The lac repressor [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1631069105000685|Comptes rendues biologies 328: 521 – 548].

- Mossakowska, Danuta E. Nyberg, Kerstin and Fersht, Alan R. (1989) Kinetic Characterization of the Recombinant Ribonuclease from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (Barnase) and Investigation of Key Residues in Catalysis by Site-Directed Mutagenesis [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/bi00435a033|Biochemistry 28: 3843 - 3850.].

- Paddon, C. J. Vasantha, N. and Hartley, R. W. (1989) Translation and Processing of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Extracellular Rnase [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC209718/pdf/jbacter00168-0575.pdf|Journal of Bacteriology 171: 1185 - 1187.].

- Voss, Carsten Lindau, Dennis and Flaschel, Erwin (2006) Production of Recombinant RNase Ba and Its Application in Downstream Processing of Plasmid DNA for Pharmaceutical Use [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1021/bp050417e/pdf|Biotechnology Progress 22: 737 - 744.].

- Walsh, Christopher (1989) Enzymes in the D-alanine branch of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan assembly. [http://www.jbc.org/content/264/5/2393.long|Journal of biological chemistry 264: 2393 - 2396.]

- Wickstrum, J.R., Santangelo, T.J., and Egan, S.M. (2005) Cyclic AMP receptor protein and RhaR synergistically activate transcription from the L-rhamnose-responsive rhaSR promoter in Escherichia coli. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1251584/?report=reader|Journal of Bacteriology 187: 6708 – 6719.].

"

"