Team:Calgary/Project/OurSensor/Reporter/BetaLactamase

From 2013.igem.org

(Created page with "<html> <div id="Banner"><h1>Beta-Lactamase</h1></div> </html> {{Team:Calgary/ContentPage}} <html> <section id="Content"> <h1>Beta-Lactamase</h1> <p>Insert Text Here</p> </se...") |

|||

| (133 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | <div id="Banner"><h1> | + | <div id="Banner"><h1>β-Lactamase</h1></div> |

</html> | </html> | ||

{{Team:Calgary/ContentPage}} | {{Team:Calgary/ContentPage}} | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<section id="Content"> | <section id="Content"> | ||

| - | <h1> | + | <h1>β-Lactamase</h1> |

| - | <p> | + | <h2>What is β-lactamase?</h2> |

| + | <p>β-lactamase is an enzyme encoded by the ampicillin resistance gene (<i>amp</i>R) frequently present in plasmids for selection. Structurally, β-lactamase is a 29 kDa monomeric enzyme (Figure 1). Its enzymatic activity provides resistance to β-lactam antibiotics such as carbapenems, penicillin and ampicillin through hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring, a structure shared by the β-lactam class of antibiotics (Qureshi, 2007).</p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/a/ad/UCalgary2013TRBetalactamaserender.png" style="width:25%;"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b>3D structure of β-lactamase made using the Embedded Python Molecular Viewer and Maya. We used spatial modeling to better understand what our proteins such as β-lactamase look like and how they interact in our system. To learn more about how we used spatial modeling to inform systems our design, click <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Project/OurSensor/Modeling">here</a>. | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | <p>Many advantages come from working with β-lactamase. It shows high catalytic efficiency and simple kinetics. Also, no orthologs of <i>amp</i>R are known to be encoded by eukaryotic cells and no toxicity was identified making this protein very useful in studies involved eukaryotes (Qureshi, 2007). β-lactamase has been used to track pathogens in infected murine models (Kong <i>et al.</i>, 2010). However, in addition to its application in eukaryotic cells,β-lactamase has been found to have an alternative application in synthetic proteins as well. β-lactamase is able to preserve its activity when fused to other proteins, meaning it can viably be used in fusion proteins (Moore <i>et al.</i>, 1997). This feature makes β-lactamase a potentially valuable tool for assembly of synthetic constructs.</p> | ||

| + | <h2>How is β-lactamase used as a Reporter?</h2> | ||

| + | <p>β-lactamase, in the presence of different substrates, can give various outputs. It can produce a fluorogenic output in the presence of a cephalosporin derivative (CCF2/AM), which can then subsequently be measured using a fluorometer (Remy <i>et al</i>., 2007). Additionally, β-lactamase can also be used to obtain colourimetric outputs by breaking down synthetic compounds such as nitrocefin (Figure 2). The result of nitrocefin hydrolysis is a colour change from yellow to red (Remy <i>et al</i>., 2007). A third output that β-lactamase can give out is through pH. One example is the hydrolysis of benzylpenicillin by β-lactamase, converting the substrate to an acid and lowering pH. This can then be seen through the use of pH indicators such as phenol red to give an observable output (Li <i>et al</i>., 2008). The multiple ways this enzyme can be used shows the versatillity of it, as it is capable of three different outputs, fluorescent, colourimetric, and pH.</p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/7/7f/YYC2013_Blac_Nitrocefin.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b> Hydrolysis of nitrocefin catalyzed by β-lactamase. This causes a colour change from yellow to red that can be seen.</a> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | <p>β-lactamase can also be split apart in to two halves for protein complementation assays, where each half is linked to one of the two proteins being tested. If the two proteins interact the two halves are able to fold into their correct structure and give an output (Wehrman <i>et al.</i>, 2002).</p> | ||

| + | <p>Therefore, this enzyme gives a lot of flexibility, both in how it can be attached to proteins as well as the various outputs it can give, making it a useful reporter to characterize and add to the Parts Registry.</p> | ||

| + | <h2>How does β-lactamase fit in our Biosensor?</h2> | ||

| + | <p>β-lactamase serves as another reporter we explored for our system in parallel to our <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Project/OurSensor/Reporter/PrussianBlueFerritin"> | ||

| + | Prussian blue ferritin reporter</a>. But unlike the Prussian Blue ferritin system, β-lactamase can also be used for a pH output as well. This would add more versatility to our system, as β-lactamase can add a different type of output which would mean that our system is not only limited to the colourimetric outputs. Additionally, the pH output can be paired with different pH indicators to give a variety of colourimetric outputs. We have characterized this ability with two separate pH indicators, phenol red and bromothymol blue, and were able to demonstrate two completely different colourimetric output. In addition, the output of our system can be scaled by altering the number of fused β-lactamase proteins by exploiting the ferritin nanoparticle. This can be achieved through modifying the number of β-lactamase molecules attached to ferritin, ranging from 24 or 12 depending on whether our ferritin nanoparticle consists of the 12 heavy-light subunit fusions (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K157018">BBa_K157018</a>),or 24 individual subunits, composed of separate light and heavy subunits. The result is a system that can be scaled by utilizing 24 or 12 β-lactamase proteins, or only 1 Prussian blue ferritin core, or one β-lactamase protein fused to a TALE as an alternate. This adds the elements of versatility, flexibility, and most importantly, modularity to our biosensor and serves a vital basis for our platform. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Constructs</h2> | ||

| + | <p>We retrieved the <i>amp</i>R gene from the backbone of the <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:pSB1A3"> | ||

| + | pSB1A3 | ||

| + | </a> plasmid. We added a a His-tag was added to the N-terminus of it using a flexible glycine linker (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K157013">BBa_K157013</a>), allowing purification through Ni-NTA protein purification, as well as the lacI promoter for expression (Figure 3). Additionaly, we modified this gene to make it a more useful part for the registry, such as the removal of a BsaI cut-site, making it viable for Golden Gate assembly (Figure 4). We also fused the <i>amp</i>R gene to on our TALE A to bind to our target sequence (Figure 5). This could be used in conjunction with another TALE to act in our strip assay. These modifications resulted in the products shown below:</p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/56/YYC_2013_Blac_constructs_001.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 3.</b> On the left, part <a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189009"> | ||

| + | BBa_K1189009</a> which is β-lactamase with a his 6 tag that facilitated purification. On the right, part <a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189007"> BBa_K1189007</a>. In addition to the His-tag, PLacI + RBS were added upstream of the β-lactamase gene so we can express and characterize our part.</p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/46/YYC_2013_Blac_Constructs_003.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 4.</b> Part <a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189008"> | ||

| + | BBa_K1189008</a>. To enable the construction of β-lactamase with Golden Gate Assembly we removed a BsaI cut site.</p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b3/YYC_2013_Blac_Constructs_002.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 5.</b> Part <a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>. This construct works as the mobile detector in our biosensor. TALE A is linked to β-lactamase and if the <i>stx2</i> gene is present in the strip, our mobile is retained on the strip so β-lactamase can give a colour output in the presence of a substrate.</p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Results</h2> | ||

| + | <p> As a preliminary test to confirm proper protein expression, we tested purified β-lactamase with benzylpenicillin, a substrate that gives a colourimetric and a pH output. First, we wanted to demonstrate that our bacteria carrying the <i>amp</i>R gene was expressing functional β-lactamase. <a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189007">BBa_K1189007</a>. In order to do so, we performed an <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/AmpicillinSurvivalAssay1"> | ||

| + | ampicillin survival assay | ||

| + | </a> using <i>E. coli</i> transformed with a plasmid encoding the <i>amp</i>R gene. This assay would involve culturing the bacteria and then exposing them to ampcillin, and survival was then measured by OD. This then allowed us to determine whether the β-lactamase was produced and whether it is functional. Only the bacteria producing functional β-lactamase enzymes were able to survive in the presence of ampicillin resulting in an increase in OD. Whereas bacteria lacking the abililty to produce functional β-lactamase enzyme were unable to survive, seen by a decrease in OD. (Figure 6). Therefore, we are able to produce functional β-lactamase enzyme (Figure 6).</p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/03/YYC2013_Blac_Amp_Survival_Assay_with_colonies.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 6. </b>Absorbance values at 600nm for each tube at four different time points: 0, 30, 60 and 120min. The cultures that expressed β-lactamase (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189007">BBa_K1189007</a>) showed higher absorbance levels, showing that the cells were able to grow in the presence of ampicillin.</a> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | <p>After confirming protein expresison, we wanted to demonstrate that we can also purify our proteins. Figure 7 demonstrates that we were able to purify both our β-lactamase (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189007">BBa_K1189007</a>) and our TALE-A-β-lactamase protein (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) (Figure 7). After purification, we wanted to demonstrate whether our purified TALE A - β-lactamase fusion protein retained its enzymatic activity. This was tested by a variation of the ampicillin survival assay where we pretreated, LB containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol, with our purified TALE A linked to β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>). We then cultured bacteria in the treated LB carrying the psB1C3 (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:pSB1C3">pSB1C3</a>), conveying resistance to chloramphenicol. In order for the bacteria to survive our isolated protein needed to retain its enzymatic abilities. We can show that the bacteria susceptible to ampicillin were able to grow in the presence of our purified proteins (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>), which means that we are expressing and purifying functional fusion protein which is degrading the ampicillin (Figures 8). Both graphs show an increase in OD for cultures pre-treated with our protein demonstrating our protein is functional.</p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/45/YYC2013_TALE_September_22_Blac.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 7. </b>On the left crude lysate of β-lactamase + His (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189007">BBa_K1189007</a>) from different lysis protocols, <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/GlassBeadsCellLysisProtocolforProteinSamples"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | beat beating | ||

| + | |||

| + | </a> and <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/OsmoticShock">sucrose osmotic shock</a> respectively. On the right, western blot of <a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K782004">TALE A</b>+linker+β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) showing that we were able to express and purify our fusion protein. | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/3/38/YYC2013_Blac_Amp_Survival_Assay_with_protein_24h.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 8. </b>Absorbance values at 600nm after 24h. Amount of protein added ranged from 0.1µg to 20µg of TALE A-link-β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) were sufficient to degrade the ampicillin in the media allowing bacteria susceptible to ampicillin to grow.</a> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/d/de/YYC2013_Blac_Amp_Survival_Assay_with_protein_3_time_points.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 9. </b>Absorbance values at 600nm in different time points. Amounts from 1.0µg to 10µg of TALE A-link-β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) were sufficient to degrade the ampicillin in the media allowing bacteria susceptible to ampicillin to grow.</a> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | <p>After verifying that <a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K782004">TALE A</a>-linker-β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031"> | ||

| + | BBa_K1189031</a>) retained enzymatic activity and was able to degrade ampicillin, we performed a <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/BenzylpenicillianAssay"> | ||

| + | pH assay</a> using benzylpenicillin as our substrate to demonstrate that our fusion TALE A - β-lactamase protein can act as a reporter. β-lactamase hydrolyzes benzylpenicillin to penicillinoic acid, which changes the pH of the solution from alkaline to acidic. We tested it out with two separate pH indicators, phenol red and bromothymol blue, and we were able to show two different colourimetric outputs. We were able to show successful reporter acitivy with both indicators. </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | We were able to see a colour change due to the presence of phenol red, a pH indicator with a transition pH of 6.8-8.2, turning red at lower pH. This pH change causes the phenol red to change from red to yellow. Our negative controls, to which benzylpenicillin was not added, remained red. We can also see the colour change coincides with the amount of purified TALE A-β-lactamase present in each sample (Figure 10). </p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/86/YYC2013_Blac_%2B_Penicillium_G.jpg"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 10. </b>Benzylpenicillin assay. On the top, the wells only had <a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K782004"> | ||

| + | TALE A</a>-linker-β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>). Benzylpenicillin was added and after a 10-minute incubation at room temperature, we were able to observe a colour output from red to yellow (bottom row) while the control wells remained red.</a> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Additionally, we have demonstrated the same pH change of benzylpenicillin to penicillinoic acid by the TALE A β-lactamase fusion (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) with bromothymol blue. The pH change causes the bromothymol blue to change in colour from blue to yellow as it gets more acidic (Figure 11 & 12). In the presence of TALE A β-lactamase fusion we see the colour change to yellow whereas the negatives not containing TALE A β-lactamase fusion remains blue (Figure 11). We did a kinetic analysis at 616 nm every 30 seconds and as the blue colour disappears, the absorbance at 616 nm decreases (Figure 12). Therefore, the lower the decrease the better the TALE A β-lactamase fusion reporter activity. Our kinetic activity shows that the biggest decrease is in our positive recombinant β-lactamase followed by the TALE A β-lactamase fusion at 10 micrograms. This decrease is lessened as we decrease the amount of TALE A β-lactamase fusion. We can also show that in our negatives with no TALE A β-lactamase fusion we do not have a decrease in absorbance. We have demonstrated the reporter activity both qualitatively (Figure 10 & 11) and quantitatively (Figure 12). </p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/c/c7/UCalgary2013TRBetalactamasecolourpsd.png" alt="Beta-lactamase Visual Assay" width="432" height="599"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 11.</b>Change in pH catalyzed by TALE A linked to β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) using benzylpenicillin. Bromothymol blue was used to keep track of this colour change. Absorbance readings were taken at 616 nm every 30 seconds. Different amounts of TALE A linked to β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) were tested. Commercial β-lactamase was used as a positive control. Negative controls included were bovine serum albumin, β-lactamase without the substrate and the substrate by itself.</p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/68/UCalgary2013TRBetalactamaseassay.png" alt="Beta-lactamase Catalytic Assay" width="800" height="442"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 12.</b>Change in pH catalyzed by TALE A linked to β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) using benzylpenicillin. Bromothymol blue was used to keep track of this colour change. Absorbance readings were taken at 616 nm every 30 seconds. Different amounts of TALE A linked to β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) were tested. Commercial β-lactamase was used as a positive control. Negative controls included were bovine serum albumin, β-lactamase without the substrate and the substrate by itself.</p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p> In order to demonstrate that we can successfully capture target DNA with two TALEs we did a capture TALE assay (Figure 13). TALE B was incubated with DNA containing target sites for TALE A and TALE B and blotted on nitrocellulose. After blocking and washing, TALE A β-lactamase fusion (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) was added to the nitrocellulose strips. The strips were transferred into a 96 well plate to which a benzylpenicillin substrate solution with phenol red was added. If the TALE A β-lactamase fusion bound to the target site for TALE A then the solution will change colour from pink to clear. If TALE A β-lactamase fusion was not present, the solution will remain pink. We can show that the first four samples which have TALE B with DNA for TALE A and TALE B show a colour change indicating that we are successfully capturing the target DNA and reporting it. Furthermore we can also show that when we add non-specific DNA we do not see a colour change demonstrating that we can successfully capture only specific DNA and report its presence with an easy visual colourimetric output. </p> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/54/TALE_B_and_TALE_A_B-lac_DNA_capture_assay.png" alt="TALE DNA Capture Assay" width="800" height="600"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <b>Figure 13: </b> TALE capture assay was done with TALE B (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189001"> | ||

| + | <b>) | ||

| + | BBa_K1189001 | ||

| + | </b></span> | ||

| + | </a >)and TALE A B-lac fusion (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031"> | ||

| + | <b> | ||

| + | BBa_K1189031 | ||

| + | </b></span> | ||

| + | </a >) and DNA (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189006"> | ||

| + | <b> | ||

| + | BBa_K1189006 | ||

| + | </b></span> </a >) | ||

| + | with both target sequences. If capture is successful, the TALE A β-lactamase is present in the well giving a colour change from pink to yellow when subjected to benzylpenicillin substrate solution within 20 minutes. The only wells that change colour are the first four wells which contain TALE B, specific DNA, and TALE A β-lactamase fusion and our positive control wells which are the controls for our fusion TALE A β-lactamase protein and our positive recombinant β-lactamase. All our other controls including our test using a non-specific sequence of DNA remained pink . This preliminary characterization data demonstrates that the TALEs are able to bind to DNA with specificity. Additionally it also shows that our system of capturing DNA with two detector TALEs and then subsequent reporting of the DNA’s presence works. | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>This assay shows that we can <span class="Yellow"><b> capture our target DNA </b></span> with two detector TALEs with <span class="Yellow"><b>specificity </b></span>. Additionally, <span class="Yellow"><b>we can report whether that DNA has been captured</b></span> and is present in the sample, which is a very important concept for our sensor system. </p> | ||

| + | <h2> Conclusion </h2> | ||

| + | <p>To conclude, we have demonstrated that we have built, expressed, purified, and submitted parts containing β-lactamase both on its own and linked to TALE A. We then expressed, purified and demonstrated the final purified products have retained their enzymatic activity. We can show activity for our mobile TALE A linked to β-lactamase (<a href=" http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K1189031">BBa_K1189031</a>) for our sensor in two different ways, through pH output (with two pH indicators) and cell growth assays. We have also demonstrated that we can use the TALE A β-lactamase fusion as a <span class="Yellow"><b> biobrick that has been characterized to show both its ability to be a good reporter and its ability to be able to bind to DNA with specificity. </b></span> </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Future Directions</h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> We would like to further characterize β-lactamase in conjunction with our ferritin nanoparticle to test the modularity of our system in our ability to scale reporter activity in response to the various sensitivities that might be required as per our platform. </p> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:43, 29 October 2013

β-Lactamase

β-Lactamase

What is β-lactamase?

β-lactamase is an enzyme encoded by the ampicillin resistance gene (ampR) frequently present in plasmids for selection. Structurally, β-lactamase is a 29 kDa monomeric enzyme (Figure 1). Its enzymatic activity provides resistance to β-lactam antibiotics such as carbapenems, penicillin and ampicillin through hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring, a structure shared by the β-lactam class of antibiotics (Qureshi, 2007).

Figure 1.3D structure of β-lactamase made using the Embedded Python Molecular Viewer and Maya. We used spatial modeling to better understand what our proteins such as β-lactamase look like and how they interact in our system. To learn more about how we used spatial modeling to inform systems our design, click here.

Many advantages come from working with β-lactamase. It shows high catalytic efficiency and simple kinetics. Also, no orthologs of ampR are known to be encoded by eukaryotic cells and no toxicity was identified making this protein very useful in studies involved eukaryotes (Qureshi, 2007). β-lactamase has been used to track pathogens in infected murine models (Kong et al., 2010). However, in addition to its application in eukaryotic cells,β-lactamase has been found to have an alternative application in synthetic proteins as well. β-lactamase is able to preserve its activity when fused to other proteins, meaning it can viably be used in fusion proteins (Moore et al., 1997). This feature makes β-lactamase a potentially valuable tool for assembly of synthetic constructs.

How is β-lactamase used as a Reporter?

β-lactamase, in the presence of different substrates, can give various outputs. It can produce a fluorogenic output in the presence of a cephalosporin derivative (CCF2/AM), which can then subsequently be measured using a fluorometer (Remy et al., 2007). Additionally, β-lactamase can also be used to obtain colourimetric outputs by breaking down synthetic compounds such as nitrocefin (Figure 2). The result of nitrocefin hydrolysis is a colour change from yellow to red (Remy et al., 2007). A third output that β-lactamase can give out is through pH. One example is the hydrolysis of benzylpenicillin by β-lactamase, converting the substrate to an acid and lowering pH. This can then be seen through the use of pH indicators such as phenol red to give an observable output (Li et al., 2008). The multiple ways this enzyme can be used shows the versatillity of it, as it is capable of three different outputs, fluorescent, colourimetric, and pH.

Figure 2. Hydrolysis of nitrocefin catalyzed by β-lactamase. This causes a colour change from yellow to red that can be seen.

β-lactamase can also be split apart in to two halves for protein complementation assays, where each half is linked to one of the two proteins being tested. If the two proteins interact the two halves are able to fold into their correct structure and give an output (Wehrman et al., 2002).

Therefore, this enzyme gives a lot of flexibility, both in how it can be attached to proteins as well as the various outputs it can give, making it a useful reporter to characterize and add to the Parts Registry.

How does β-lactamase fit in our Biosensor?

β-lactamase serves as another reporter we explored for our system in parallel to our Prussian blue ferritin reporter. But unlike the Prussian Blue ferritin system, β-lactamase can also be used for a pH output as well. This would add more versatility to our system, as β-lactamase can add a different type of output which would mean that our system is not only limited to the colourimetric outputs. Additionally, the pH output can be paired with different pH indicators to give a variety of colourimetric outputs. We have characterized this ability with two separate pH indicators, phenol red and bromothymol blue, and were able to demonstrate two completely different colourimetric output. In addition, the output of our system can be scaled by altering the number of fused β-lactamase proteins by exploiting the ferritin nanoparticle. This can be achieved through modifying the number of β-lactamase molecules attached to ferritin, ranging from 24 or 12 depending on whether our ferritin nanoparticle consists of the 12 heavy-light subunit fusions (BBa_K157018),or 24 individual subunits, composed of separate light and heavy subunits. The result is a system that can be scaled by utilizing 24 or 12 β-lactamase proteins, or only 1 Prussian blue ferritin core, or one β-lactamase protein fused to a TALE as an alternate. This adds the elements of versatility, flexibility, and most importantly, modularity to our biosensor and serves a vital basis for our platform.

Constructs

We retrieved the ampR gene from the backbone of the pSB1A3 plasmid. We added a a His-tag was added to the N-terminus of it using a flexible glycine linker (BBa_K157013), allowing purification through Ni-NTA protein purification, as well as the lacI promoter for expression (Figure 3). Additionaly, we modified this gene to make it a more useful part for the registry, such as the removal of a BsaI cut-site, making it viable for Golden Gate assembly (Figure 4). We also fused the ampR gene to on our TALE A to bind to our target sequence (Figure 5). This could be used in conjunction with another TALE to act in our strip assay. These modifications resulted in the products shown below:

Figure 3. On the left, part BBa_K1189009 which is β-lactamase with a his 6 tag that facilitated purification. On the right, part BBa_K1189007. In addition to the His-tag, PLacI + RBS were added upstream of the β-lactamase gene so we can express and characterize our part.

Figure 4. Part BBa_K1189008. To enable the construction of β-lactamase with Golden Gate Assembly we removed a BsaI cut site.

Figure 5. Part BBa_K1189031. This construct works as the mobile detector in our biosensor. TALE A is linked to β-lactamase and if the stx2 gene is present in the strip, our mobile is retained on the strip so β-lactamase can give a colour output in the presence of a substrate.

Results

As a preliminary test to confirm proper protein expression, we tested purified β-lactamase with benzylpenicillin, a substrate that gives a colourimetric and a pH output. First, we wanted to demonstrate that our bacteria carrying the ampR gene was expressing functional β-lactamase. BBa_K1189007. In order to do so, we performed an ampicillin survival assay using E. coli transformed with a plasmid encoding the ampR gene. This assay would involve culturing the bacteria and then exposing them to ampcillin, and survival was then measured by OD. This then allowed us to determine whether the β-lactamase was produced and whether it is functional. Only the bacteria producing functional β-lactamase enzymes were able to survive in the presence of ampicillin resulting in an increase in OD. Whereas bacteria lacking the abililty to produce functional β-lactamase enzyme were unable to survive, seen by a decrease in OD. (Figure 6). Therefore, we are able to produce functional β-lactamase enzyme (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Absorbance values at 600nm for each tube at four different time points: 0, 30, 60 and 120min. The cultures that expressed β-lactamase (BBa_K1189007) showed higher absorbance levels, showing that the cells were able to grow in the presence of ampicillin.

After confirming protein expresison, we wanted to demonstrate that we can also purify our proteins. Figure 7 demonstrates that we were able to purify both our β-lactamase (BBa_K1189007) and our TALE-A-β-lactamase protein (BBa_K1189031) (Figure 7). After purification, we wanted to demonstrate whether our purified TALE A - β-lactamase fusion protein retained its enzymatic activity. This was tested by a variation of the ampicillin survival assay where we pretreated, LB containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol, with our purified TALE A linked to β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031). We then cultured bacteria in the treated LB carrying the psB1C3 (pSB1C3), conveying resistance to chloramphenicol. In order for the bacteria to survive our isolated protein needed to retain its enzymatic abilities. We can show that the bacteria susceptible to ampicillin were able to grow in the presence of our purified proteins (BBa_K1189031), which means that we are expressing and purifying functional fusion protein which is degrading the ampicillin (Figures 8). Both graphs show an increase in OD for cultures pre-treated with our protein demonstrating our protein is functional.

Figure 7. On the left crude lysate of β-lactamase + His (BBa_K1189007) from different lysis protocols, beat beating and sucrose osmotic shock respectively. On the right, western blot of TALE A+linker+β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) showing that we were able to express and purify our fusion protein.

Figure 8. Absorbance values at 600nm after 24h. Amount of protein added ranged from 0.1µg to 20µg of TALE A-link-β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) were sufficient to degrade the ampicillin in the media allowing bacteria susceptible to ampicillin to grow.

Figure 9. Absorbance values at 600nm in different time points. Amounts from 1.0µg to 10µg of TALE A-link-β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) were sufficient to degrade the ampicillin in the media allowing bacteria susceptible to ampicillin to grow.

After verifying that TALE A-linker-β-lactamase ( BBa_K1189031) retained enzymatic activity and was able to degrade ampicillin, we performed a pH assay using benzylpenicillin as our substrate to demonstrate that our fusion TALE A - β-lactamase protein can act as a reporter. β-lactamase hydrolyzes benzylpenicillin to penicillinoic acid, which changes the pH of the solution from alkaline to acidic. We tested it out with two separate pH indicators, phenol red and bromothymol blue, and we were able to show two different colourimetric outputs. We were able to show successful reporter acitivy with both indicators.

We were able to see a colour change due to the presence of phenol red, a pH indicator with a transition pH of 6.8-8.2, turning red at lower pH. This pH change causes the phenol red to change from red to yellow. Our negative controls, to which benzylpenicillin was not added, remained red. We can also see the colour change coincides with the amount of purified TALE A-β-lactamase present in each sample (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Benzylpenicillin assay. On the top, the wells only had TALE A-linker-β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031). Benzylpenicillin was added and after a 10-minute incubation at room temperature, we were able to observe a colour output from red to yellow (bottom row) while the control wells remained red.

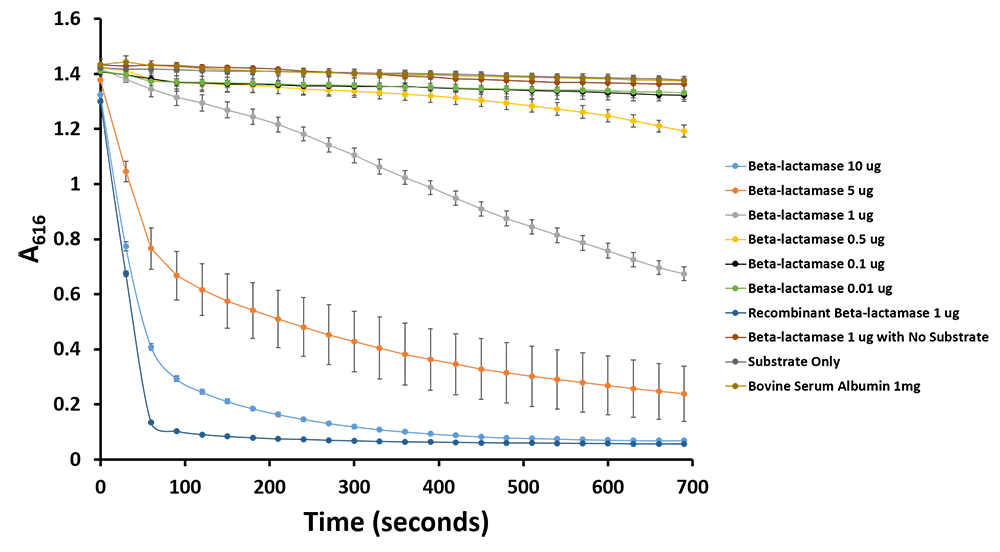

Additionally, we have demonstrated the same pH change of benzylpenicillin to penicillinoic acid by the TALE A β-lactamase fusion (BBa_K1189031) with bromothymol blue. The pH change causes the bromothymol blue to change in colour from blue to yellow as it gets more acidic (Figure 11 & 12). In the presence of TALE A β-lactamase fusion we see the colour change to yellow whereas the negatives not containing TALE A β-lactamase fusion remains blue (Figure 11). We did a kinetic analysis at 616 nm every 30 seconds and as the blue colour disappears, the absorbance at 616 nm decreases (Figure 12). Therefore, the lower the decrease the better the TALE A β-lactamase fusion reporter activity. Our kinetic activity shows that the biggest decrease is in our positive recombinant β-lactamase followed by the TALE A β-lactamase fusion at 10 micrograms. This decrease is lessened as we decrease the amount of TALE A β-lactamase fusion. We can also show that in our negatives with no TALE A β-lactamase fusion we do not have a decrease in absorbance. We have demonstrated the reporter activity both qualitatively (Figure 10 & 11) and quantitatively (Figure 12).

Figure 11.Change in pH catalyzed by TALE A linked to β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) using benzylpenicillin. Bromothymol blue was used to keep track of this colour change. Absorbance readings were taken at 616 nm every 30 seconds. Different amounts of TALE A linked to β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) were tested. Commercial β-lactamase was used as a positive control. Negative controls included were bovine serum albumin, β-lactamase without the substrate and the substrate by itself.

Figure 12.Change in pH catalyzed by TALE A linked to β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) using benzylpenicillin. Bromothymol blue was used to keep track of this colour change. Absorbance readings were taken at 616 nm every 30 seconds. Different amounts of TALE A linked to β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) were tested. Commercial β-lactamase was used as a positive control. Negative controls included were bovine serum albumin, β-lactamase without the substrate and the substrate by itself.

In order to demonstrate that we can successfully capture target DNA with two TALEs we did a capture TALE assay (Figure 13). TALE B was incubated with DNA containing target sites for TALE A and TALE B and blotted on nitrocellulose. After blocking and washing, TALE A β-lactamase fusion (BBa_K1189031) was added to the nitrocellulose strips. The strips were transferred into a 96 well plate to which a benzylpenicillin substrate solution with phenol red was added. If the TALE A β-lactamase fusion bound to the target site for TALE A then the solution will change colour from pink to clear. If TALE A β-lactamase fusion was not present, the solution will remain pink. We can show that the first four samples which have TALE B with DNA for TALE A and TALE B show a colour change indicating that we are successfully capturing the target DNA and reporting it. Furthermore we can also show that when we add non-specific DNA we do not see a colour change demonstrating that we can successfully capture only specific DNA and report its presence with an easy visual colourimetric output.

Figure 13: TALE capture assay was done with TALE B ( ) BBa_K1189001 )and TALE A B-lac fusion ( BBa_K1189031 ) and DNA ( BBa_K1189006 ) with both target sequences. If capture is successful, the TALE A β-lactamase is present in the well giving a colour change from pink to yellow when subjected to benzylpenicillin substrate solution within 20 minutes. The only wells that change colour are the first four wells which contain TALE B, specific DNA, and TALE A β-lactamase fusion and our positive control wells which are the controls for our fusion TALE A β-lactamase protein and our positive recombinant β-lactamase. All our other controls including our test using a non-specific sequence of DNA remained pink . This preliminary characterization data demonstrates that the TALEs are able to bind to DNA with specificity. Additionally it also shows that our system of capturing DNA with two detector TALEs and then subsequent reporting of the DNA’s presence works.

This assay shows that we can capture our target DNA with two detector TALEs with specificity . Additionally, we can report whether that DNA has been captured and is present in the sample, which is a very important concept for our sensor system.

Conclusion

To conclude, we have demonstrated that we have built, expressed, purified, and submitted parts containing β-lactamase both on its own and linked to TALE A. We then expressed, purified and demonstrated the final purified products have retained their enzymatic activity. We can show activity for our mobile TALE A linked to β-lactamase (BBa_K1189031) for our sensor in two different ways, through pH output (with two pH indicators) and cell growth assays. We have also demonstrated that we can use the TALE A β-lactamase fusion as a biobrick that has been characterized to show both its ability to be a good reporter and its ability to be able to bind to DNA with specificity.

Future Directions

We would like to further characterize β-lactamase in conjunction with our ferritin nanoparticle to test the modularity of our system in our ability to scale reporter activity in response to the various sensitivities that might be required as per our platform.

"

"