Team:Duke/Project/Basics

From 2013.igem.org

Hyunsoo kim (Talk | contribs) (→Characteristics of Genetic Toggle Switches) |

Hyunsoo kim (Talk | contribs) (→Characteristics of Genetic Toggle Switches) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==Characteristics of Genetic Toggle Switches== | ==Characteristics of Genetic Toggle Switches== | ||

| - | Genetic Toggle Switches have several characteristics which make them unique from other Gene Regulatory networks. For example, Genetic Toggle Switches must be capable of bi-stable behavior, meaning that they should only exist in one of two stable states instead of in a variety of intermediate states. Bi-stability also suggests that a certain threshold must be passed before the toggle switch can switch from one state to another. In addition, toggle switches should have low transcriptional noise to prevent random switching without | + | Genetic Toggle Switches have several characteristics which make them unique from other Gene Regulatory networks. For example, Genetic Toggle Switches must be capable of bi-stable behavior, meaning that they should only exist in one of two stable states instead of in a variety of intermediate states. Bi-stability also suggests that a certain threshold must be passed before the toggle switch can switch from one state to another. In addition, toggle switches should have low transcriptional noise to prevent random switching without induction. Finally, a reporter or marker structural gene, such as a fluorescent protein, should be present in order to characterize the effectiveness of the toggle switch. <From: iGEM 2011 Team Duke> |

Revision as of 04:51, 18 September 2013

Contents |

Background Information

Genetic Toggle Switch

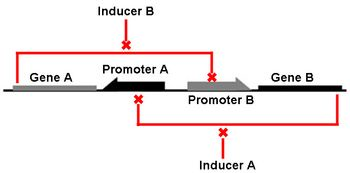

The Genetic Toggle Switch was among the first artificially constructed Gene Regulatory Networks. The original Genetic Toggle Switch consisted of the ptrc-2 (lacI repressible) promoter paired with the temperature sensitive lambda repressor and the PLs1con (lambda repressible) promoter paired with the lacI repressor. Subsequently, induction of the ptrc-2 promoter would repress the PLs1con promoter through expression of the lambda repressor, while induction of the PLs1con promoter would repress the ptrc-2 promoter through expression of the lacI repressor. Switching of the toggle switch from one promoter to another was accomplished by addition of either Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), which causes the lacI to unbind allowing the ptrc-2 to switch on, or a thermal pulse, which causes the lambda repressor to unbind and allow the PLs1con promoter to switch on. In order to characterize the toggle switch, a GFPmut3 structural gene was placed downstream of the Ptrc-2 promoter so that induction of the Ptrc-2 promoter would result in high expression of GFPmut3 while induction of PLs1con would result in low expression of GFPmut3.

Characteristics of Genetic Toggle Switches

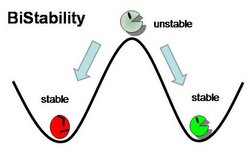

Genetic Toggle Switches have several characteristics which make them unique from other Gene Regulatory networks. For example, Genetic Toggle Switches must be capable of bi-stable behavior, meaning that they should only exist in one of two stable states instead of in a variety of intermediate states. Bi-stability also suggests that a certain threshold must be passed before the toggle switch can switch from one state to another. In addition, toggle switches should have low transcriptional noise to prevent random switching without induction. Finally, a reporter or marker structural gene, such as a fluorescent protein, should be present in order to characterize the effectiveness of the toggle switch. <From: iGEM 2011 Team Duke>

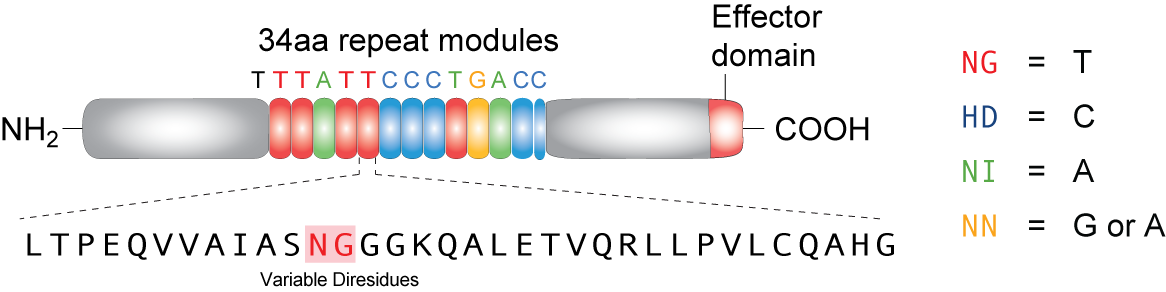

TAL Effector

TAL effector (Transcription Activator-Like effector or TALEs) are proteins derived from bacteria (Xanthomonas) that often infect plants. In its native form, these proteins can target DNA sequences in host plants to trigger expression of genes that help bacterial infection. A highly repetitive region in the middle of the protein, consisting 33~34 amino acids, only vary in amino acid at positions 12 and 13. These two amino acids, which are refered to as RVD's (repeat variable di-residues) can be genetically engineered to target desired sequences. Four RVD's--named NG, HD, NI, and NN--bind to each of the four nucleotides T, C, A and G respectively (NN can bind to both G and A). Recent studies showed that these proteins can be artificially designed and coded to target specific DNA sequences in different types of cells, including plant and mammalian cells, proving its vertile usage as an effective tool in genetic engineering.

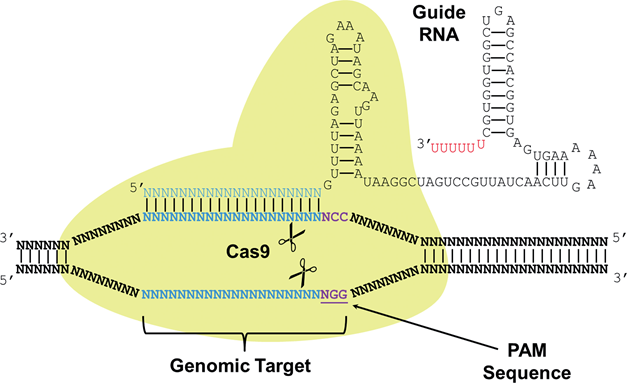

CRISPR

CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, and these are commonly found in archaea (~90%) and in bacteria (~40%). CRISPRs function as bacterial immune response, where it helps recognize foreign DNA and silence it by interacting with CAS (CRISPR-associated) proteins that have nuclease or helicase activity. A small RNA called sgRNA (small-guide RNA) recognize a specific DNA sequence, and its secondary structure forms a region called Cas9 handle, at which the Cas proteins bind to silence the targeted DNA. The recent discovery of CRISPR-CAS system as a tool for genetic engineering and synthetic biology enabled target-specific manipulation of genes. Specifically, by engineering sgRNA sequences that match the target DNA sequences, it forms a complex with Cas protein (Cas9, having nuclease activity) to cut the target gene. Also, by using mutated nuclease-deficient Cas9 protein (dCas9), engineering site-specific proteins that can act as transcription factors (repressors) is possible.

References

DiCarlo et al., 2013

- Gardener, T. et al. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature. 403, 339-342 (2000).

- TAL Effectors Resources. Introduction to TAL Effectors. Accessd on 9/3/13 <http://www.genome-engineering.org/taleffectors/>.

- DiCarlo, J. et al. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Research. 41(7), 4336-4343 (2013).

"

"